Lateral flow test

Lateral flow tests,[1] also known as lateral flow immunochromatographic assays or rapid tests, are simple devices intended to detect the presence of a target substance in a liquid sample without the need for specialized and costly equipment. These tests are widely used in medical diagnostics for home testing, point of care testing, or laboratory use. For instance, the home pregnancy test is a lateral flow test that detects a certain hormone. These tests are simple, economic and generally show results in around 5-30 minutes.[2] Many lab-based applications increase the sensitivity of simple lateral flow tests by employing additional dedicated equipment.[3]

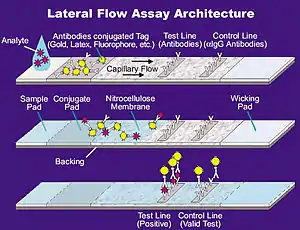

Lateral flow tests operate on the same principles as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). In essence, these tests run the liquid sample along the surface of a pad with reactive molecules that show a visual positive or negative result. The pads are based on a series of capillary beds, such as pieces of porous paper,[4] microstructured polymer,[5][6] or sintered polymer.[7] Each of these pads has the capacity to transport fluid (e.g., urine, blood, saliva) spontaneously.

The sample pad acts as a sponge and holds an excess of sample fluid. Once soaked, the fluid flows to the second conjugate pad in which the manufacturer has stored freeze dried bio-active particles called conjugates (see below) in a salt-sugar matrix. The conjugate pad contains all the reagents required for an optimized chemical reaction between the target molecule (e.g., an antigen) and its chemical partner (e.g., antibody) that has been immobilized on the particle's surface. This marks target particles as they pass through the pad and continue across to the test and control lines. The test line shows a signal, often a color as in pregnancy tests. The control line contains affinity ligands which show whether the sample has flowed through and the bio-molecules in the conjugate pad are active. After passing these reaction zones, the fluid enters the final porous material, the wick, that simply acts as a waste container.

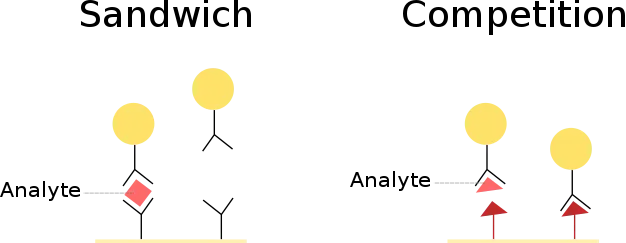

Lateral flow tests can operate as either competitive or sandwich assays.

Colored particles

In principle, any colored particle can be used, however latex (blue color) or nanometer sized particles[8] of gold (red color) are most commonly used. The gold particles are red in color due to localized surface plasmon resonance.[9] Fluorescent[10] or magnetic[11][12] labelled particles can also be used, however these require the use of an electronic reader to assess the test result.

Sandwich assays

Sandwich assays are generally used for larger analytes because they tend to have multiple binding sites.[13] As the sample migrates through the assay it first encounters a conjugate, which is an antibody specific to the target analyte labelled with a visual tag, usually colloidal gold. The antibodies bind to the target analyte within the sample and migrate together until they reach the test line. The test line also contains immobilized antibodies specific to the target analyte, which bind to the migrated analyte bound conjugate molecules. The test line then presents a visual change due to the concentrated visual tag, hence confirming the presence of the target molecules. The majority of sandwich assays also have a control line which will appear whether or not the target analyte is present to ensure proper function of the lateral flow pad.

The rapid, low-cost sandwich-based assay is commonly used for home pregnancy tests which detect human chorionic gonadotropin, hCG, in the urine of pregnant women.

Competitive assays

Competitive assays are generally used for smaller analytes since smaller analytes have fewer binding sites.[14] The sample first encounters antibodies to the target analyte labelled with a visual tag (colored particles). The test line contains the target analyte fixed to the surface. When the target analyte is absent from the sample, unbound antibody will bind to these fixed analyte molecules, meaning that a visual marker will show. Conversely, when the target analyte is present in the sample, it binds to the antibodies to prevent them binding to the fixed analyte in the test line, and thus no visual marker shows. This differs from sandwich assays in that no band means the analyte is present.

Quantitative tests

Most tests are intended to operate on a purely qualitative basis. However it is possible to measure the intensity of the test line to determine the quantity of analyte in the sample. Handheld diagnostic devices known as lateral flow readers are used by several companies to provide a fully quantitative assay result. By utilizing unique wavelengths of light for illumination in conjunction with either CMOS or CCD detection technology, a signal rich image can be produced of the actual test lines. Using image processing algorithms specifically designed for a particular test type and medium, line intensities can then be correlated with analyte concentrations. One such handheld lateral flow device platform is made by Detekt Biomedical L.L.C..[15] Alternative non-optical techniques are also able to report quantitative assays results. One such example is a magnetic immunoassay (MIA) in the lateral flow test form also allows for getting a quantified result. Reducing variations in the capillary pumping of the sample fluid is another approach to move from qualitative to quantitative results. Recent work has, for example, demonstrated capillary pumping with a constant flow rate independent from the liquid viscosity and surface energy.[6][16][17][18]

Mobile phones have demonstrated to have a strong potential for the quantification in lateral flow assays, not only by using the camera of the device, but also the light sensor or the energy supplied by the mobile phone battery.[19]

Control line

While not strictly necessary, most tests will incorporate a second line which contains an antibody that picks up free latex/gold in order to confirm the test has operated correctly.

Blood plasma extraction

Because the intense red color of hemoglobin interferes with the readout of colorimetric or optical detection-based diagnostic tests, blood plasma separation is a common first step to increase diagnostic test accuracy. Plasma can be extracted from whole blood via integrated filters[20] or via agglutination.[21]

Speed and simplicity

Time to obtain the test result is a key driver for these products. Tests can take as little as a few minutes to develop. Generally there is a trade off between time and sensitivity: more sensitive tests may take longer to develop. The other key advantage of this format of test compared to other immunoassays is the simplicity of the test, by typically requiring little or no sample or reagent preparation.

Patents

This is a highly competitive area and a number of people claim patents in the field, most notably Alere (formerly Inverness Medical Innovations, now owned by Abbott) who own patents[22] originally filed by Unipath. A group of competitors are challenging the validity of the patents.[23] A number of other companies also hold patents in this arena.

Applications

Lateral flow assays have a wide array of applications and can test a variety of samples like urine, blood, saliva, sweat, serum, and other fluids. They are currently used by clinical laboratories, hospitals, and physicians for quick and accurate tests for specific target molecules and gene expression. Other uses for lateral flow assays are food and environmental safety and veterinary medicine for chemicals such as diseases and toxins.[24] Lateral flow tests are also commonly used for disease identification such as ebola, but the most common lateral flow test is the home pregnancy test.

COVID-19 testing

Lateral flow assays have played a critical role in COVID-19 testing as they have the benefit of delivering a result in 15-30 minutes.[25] The systematic evaluation of lateral flow assays during the COVID-19 pandemic[26] was initiated at Oxford University as part of a UK collaboration with Public Health England. A study which started in June 2020 in the United Kingdom, FALCON-C19, confirmed the sensitivity of some lateral flow devices (LFDs) in this setting.[27][28][29] Four out of 64 LFDs tested had desirable performance characteristics; the Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Qualitative Test, in particular, underwent extended clinical assessment in field studies and was found to have good viral antigen detection/sensitivity with excellent specificity, although kit failure rates and the impact of training were potential issues.[28] Following evaluation, it was decided in January 2021 to open secondary schools in England, with pupils and teachers taking daily lateral flow tests, part of what was termed "Operation Moonshot". However, the medicines regulator did not authorise daily rapid-turnaround tests as an alternative to self-isolation.[30]

Lateral flow tests have been used for mass testing for COVID-19 globally[31][32][33] and complement other public health measures for COVID-19.[34]

Some scientists outside government have expressed serious misgivings about the use of LFDs for screening for Covid. According to Jon Deeks, a professor of biostatistics at the University of Birmingham, England, the test is "entirely unsuitable" for community testing: "as the test may miss up to half of cases, a negative test result indicates a reduced risk of Covid, but does not exclude Covid".[35][36] Following criticism by experts and lack of authorisation by the regulator, the UK government "paused" the daily lateral flow tests in English schools in mid-January 2021.[30]

References

- Concurrent Engineering for Lateral-Flow Diagnostics (IVDT archive, Nov 99) Archived 2014-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Koczula, Katarzyna M.; Gallotta, Andrea (2016-06-30). "Lateral flow assays". Essays in Biochemistry. 60 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1042/EBC20150012. ISSN 0071-1365. PMC 4986465. PMID 27365041.

- Yetisen A. K. (2013). "Paper-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices". Lab on a Chip. 13 (12): 2210–2251. doi:10.1039/C3LC50169H. PMID 23652632. S2CID 17745196.

- "Lateral Flow Introduction". khufash.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- Jonas Hansson; Hiroki Yasuga; Tommy Haraldsson; Wouter van der Wijngaart (2016). "Synthetic microfluidic paper: high surface area and high porosity polymer micropillar arrays". Lab on a Chip. 16 (2): 298–304. doi:10.1039/C5LC01318F. PMID 26646057.

- Weijin Guo; Jonas Hansson; Wouter van der Wijngaart (2016). "Viscosity Independent Paper Microfluidic Imbibition" (PDF). MicroTAS 2016, Dublin, Ireland.

- "Sample Collection & Transport | Sample Preparation | Sample Analysis".

- Quesada-González, Daniel; Merkoçi, Arben (2015). "Nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensors". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 15 (special): 47–63. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2015.05.050. hdl:10261/131760. PMID 26043315.

- NanoHybrids. "Gold Nanoparticle Labels Custom Designed for Lateral Flow Assays". NanoHybrids. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- (Point-of-Care Technologies) Developing rapid mobile POC systems - Part 1: Devices and applications for lateral-flow immunodiagnostics (IVDT archive, Jul 07)

- Paramagnetic-particle detection in lateral-flow assays (IVDT archive, Apr 02)

- "Magnetic immunoassays: A new paradigm in POCT (IVDT archive, Jul/Aug 2008)". Archived from the original on 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- nanoComposix. "Introduction to Lateral Flow Rapid Test Diagnostics". nanoComposix. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- nanoComposix. "Introduction to Lateral Flow Rapid Test Diagnostics". nanoComposix. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- "Detekt Biomedical L.L.C.- Lateral Flow Readers for Rapid Test Strip Detection and Immunoassays". idetekt.com. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- Weijin Guo; Jonas Hansson; Wouter van der Wijngaart (2016). "Capillary Pumping Independent of Liquid Sample Viscosity". Langmuir. 32 (48): 12650–12655. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03488. PMID 27798835.

- Weijin Guo; Jonas Hansson; Wouter van der Wijngaart (2017). Capillary pumping with a constant flow rate independent of the liquid sample viscosity and surface energy. IEEE MEMS 2017, las Vegas, USA. pp. 339–341. doi:10.1109/MEMSYS.2017.7863410. ISBN 978-1-5090-5078-9.

- Weijin Guo; Jonas Hansson; Wouter van der Wijngaart (2018). "Capillary pumping independent of the liquid surface energy and viscosity". Microsystems & Nanoengineering. 4 (1): 2. Bibcode:2018MicNa...4....2G. doi:10.1038/s41378-018-0002-9. PMC 6220164. PMID 31057892.

- Quesada-González, Daniel; Merkoçi, Arben (2017-06-15). "Mobile phone-based biosensing: An emerging "diagnostic and communication" technology". Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 92: 549–562. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2016.10.062. hdl:10261/160220. ISSN 0956-5663. PMID 27836593.

- Tripathi S, Kumar V, Prabhakar A, Joshi S, Agrawal A (2015). "Passive blood plasma separation at the microscale: a review of design principles and microdevices". J. Micromech. Microeng. 25 (8): 083001. Bibcode:2015JMiMi..25h3001T. doi:10.1088/0960-1317/25/8/083001.

- Guo, Weijin; Hansson, Jonas; van der Wijngaart, Wouter (2020). "Synthetic Paper Separates Plasma from Whole Blood with Low Protein Loss". Analytical Chemistry. 92 (9): 6194–6199. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01474. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 32323979.

- U.S. Patent No. 6,485,982

- "Grassroots Web group challenging lateral-flow patents". Medical DeviceLink. November 2000. Archived from the original on 2001-07-08.

- Koczula, Katarzyna M.; Gallotta, Andrea (2016-06-30). "Lateral flow assays". Essays in Biochemistry. 60 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1042/EBC20150012. ISSN 0071-1365. PMC 4986465. PMID 27365041.

- Guglielmi, Giorgia (2020-09-16). "Fast coronavirus tests: what they can and can't do". Nature. 585 (7826): 496–498. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02661-2.

- "Guidance: First wave of non-machine based lateral flow technology (LFT) assessment". GOV.UK. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Oxford University and PHE confirm high-sensitivity of lateral flow tests". GOV.UK. 2020-11-11.

- "FALCON — CONDOR Platform". www.condor-platform.org. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- Peto, Tim (15 January 2021). "COVID-19: Rapid Antigen detection for SARS-CoV-2 by lateral flow assay: a national systematic evaluation for mass-testing". medRxiv, the preprint server for health sciences. doi:10.1101/2021.01.13.21249563.

- Halliday, Josh (19 January 2021). "Ministers set to halt plans for daily Covid tests in English schools". The Guardian.

- "Slovakia carries out Covid mass testing of two-thirds of population". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 2020-11-02. ISSN 0261-3077.

- Peter Littlejohns (2020-11-06). "The UK is trialling lateral flow testing for Covid-19 – how does it work?". NS Medical Devices.

- "Merthyr Tydfil County Borough to be first whole area testing pilot in Wales". GOV.WALES. 2020-11-18.

- "Population-wide testing of SARS-CoV-2: country experiences and potential approaches in the EU/EEA and the United Kingdom". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2020-08-19.

- Burke, Maria (18 November 2020). "Scientists urge caution on use of lateral flow tests to screen for Covid-19". Chemistry World. Criticism of LFDs for Covid testing by several experts, with detailed numerical discussion.

- Deeks, Jon; Raffle, Angela; Gill, Mike (12 January 2021). "Covid-19: government must urgently rethink lateral flow test roll out". The BMJ Opinion.