Lawrence Ogilvie

Lawrence Ogilvie (5 July 1898 – 16 April 1980) was a Scottish plant pathologist.

Lawrence Ogilvie | |

|---|---|

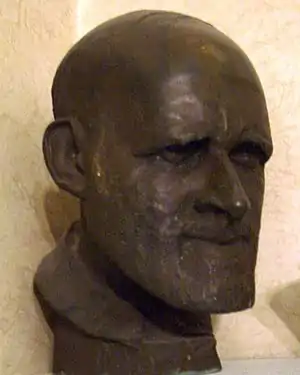

Ogilvie in his Bermuda Department of Agriculture laboratory in the mid-1920s | |

| Born | 5 July 1898 The Manse, Rosehearty, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Died | 16 April 1980 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Known for | Plant pathology of crops in Bermuda 1923-1928 and Britain 1928-1965, entomology in Bermuda |

| Spouse(s) | Doris Katherine Raikes Turnbull |

Ogilvie was a UK expert[1] on the diseases of commercially grown vegetables and wheat from the 1930s to the 1960s.

In the 1920s – when agriculture, rather than tourism, was Bermuda's major industry – he identified the virus that had devastated for 30 years the island's lily-bulb crop. He re-established the vital export trade to the USA and increased it to seven-fold the volume of ten years earlier.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

In total he wrote over 130 articles about plant diseases in journals of learned societies.

Early life

Lawrence was born in Rosehearty, a fishing village on the north coast of Aberdeenshire, Scotland, on 5 July 1898. His father, the Reverend William Paton Ogilvie, was the minister of the Presbyterian church there. He attended Aberdeen Grammar School[8] and took his BSc and MA at the University of Aberdeen in 1921 as the Fullerton Research Scholar with special distinction in Botany and Zoology. He was also awarded the Collie Prize for the most distinguished student in Botany. In Aberdeen, he lectured on the Alpine flora of China.[9] At Emmanuel College, Cambridge University he studied plant pathology and was awarded an MSc in 1923 for his work on tree slime fluxes, particularly willow, elm, horse chestnut, and apple trees.[10][11]

Career

He was to be continuously employed from September 1923, in Bermuda, until he retired, at the age of 65, in Bristol.

At age 71, working from home, he researched necessary changes and published his sixth edition of the British government's official national Diseases of Vegetables Bulletin 123 110-page guide for commercial growers[12] – his first edition of 84 pages was published in July 1941 when food was rationed and in short supply due to WWII. The bulletin was also translated into Spanish and published in 1964 as Enfermedades de las Hortalizas.

On graduating at Cambridge University he was offered to be the first scientifically trained plant pathologist and entomologist to work in either of the then British colonies of Bermuda or Mauritius. He chose Bermuda.

Bermuda

From September 1923 to April 1928 he was the Bermuda government's first plant pathologist and entomologist. He developed agricultural laws for Bermuda; initiated seed testing; registered local seedsmen; organised the improvement of seed potatoes; established plant quarantine; studied the diseases of celery and other vegetables, maize, vines, avocados, bananas and citrus fruits; and investigated the banana losses from the Mediterranean Fruit Fly.[3][13][14][15][16]

As the Bermuda delegate at the Kingston, Jamaica 8th West Indian Agricultural Conference in March 1924, he initiated West Indian plant inspections,[17] nursery-stock export certificates, and the inspection and grading of fruit and vegetables for export.

He was acclaimed in Bermuda for identifying the virus that had increasingly damaged the commercially vital lily-bulb export trade of Lilium longiflorum Lilium Harrisii to the USA since the late 19th century.[3][4][5][6][7][2] Aphid damage had previously been thought to be the cause of the crop failures. He identified the virus as transmitted by an aphid: Aphis lilii Takahashi. Following establishing strong government inspection in the fields and packing stations, he reported the marked improvements found during his 1927 inspections of 204 bulb fields of these lilies. Exports of Bermuda Easter lilies increased from 823 cases in 1918 to 6043 cases in 1927.[18][19] Due to this success being published in the renowned Nature magazine, and while still in his 20s, Ogilvie was made a vice-president of the British Lily Society.[20]

Ogilvie wrote The Insects of Bermuda,[21][22] published in 1928 by the Department of Agriculture, Bermuda. He identified and described 395 insects;[23] in particular the Aphid ogilviei discovered by him on Lilium Harrisii in Bermuda.[24][25]

Bermuda had three crops of vegetables each year for export to New York: this gave him the experience to later pioneer the European study of vegetable diseases.[26]

England

In the winter of 1928 he was appointed Advisory Mycologist at Long Ashton Research Station near Bristol, England.[27] The Vale of Evesham, Cornwall, and other West Country areas grew and grow much of Britain's vegetables.[28] He pioneered the European study of commercial fruit[29][30] and particularly vegetable diseases[31][32][33][34][35] with 44 scientific papers between 1929 and 1946 at Long Ashton Research Station. He wrote the government's official national Diseases of Vegetables[12] practical guide for trade growers: the six editions from 1941 to 1969 (in 1969, retired and aged 71) were full of photos of wilting crops.[1][36]

Ogilvie was influential in the World War II and post-war challenge of feeding Britain: he was the leading British expert[26] on the diseases of cereal crops[37] and vegetables. By the 1940s, wheat varieties had not been sufficiently bred to resist the rust and other diseases in the damp climate prevalent in Britain and particularly in the south west where he was responsible for advising farmers. Before the war, Britain imported half its food, but by 1941 relied on home-grown crops because German submarines were sinking about 60 merchant ships per month, and the priority for shipping was to carry matériel to resist the impending invasion. The 1940s varieties of wheat were still unable to resist disease, with long stalks prone to lodging in the heavy rains of the west of England.

He was the international authority on the diseases of wheat that flourished in these British damp, warm conditions – particularly Black Stem Rust[38][39][40][41][42] and Take All.[43][44]

_Duncan_Ogilvie_1941_-_and_Duncan_later.jpg.webp)

Ogilvie and his team of scientists advised growers and farmers in the south-west of England through the war years and until his retirement in 1963.[45][46][47][48] This was particularly important to Britain during the war and the continued food rationing period to 1954[49][50] – bread for instance was rationed from 1946 to 1948, even though it was not rationed during the war.

Ogilvie was elected a vice president of the British Mycological Society in December 1956.[51]

Personal life

On 10 January 1931 in the Bessels Green, Sevenoaks Unitarian Meeting House,[52] Lawrence Ogilvie married landscape-architect Doris Katherine Raikes Turnbull, whom he had met while working in Bermuda. They then lived in the hamlet East Dundry, close to the southern side of Bristol.

Doris was born in 14 November 1698, the same year as Lawrence – but in Nowgong (now Nagaon), Assam, India, the daughter of a tea planter. She complemented Lawrence's botanical knowledge, having studied horticulture in Swanley, Kent in England; teaching gardening at La Corbière école horticole pour jeunes filles in Estavayer-le-Lac by the shores of Lake Neuchatel in Switzerland; studying from 1924 at the Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture in Groton, Massachusetts (one of the first colleges to teach women landscape architecture); meeting her future husband while working for the public gardens in Bermuda; from April 1925 establishing the three-acre garden of Ilaro Court which later became the official residence of the Prime Ministers of Barbados;[53] developing and maintaining their garden in East Dundry; and coping there with no electricity or gas, a well, a large kitchen garden, an orchard, hens, goats, bee hives, and the heavy Nazi bombing of nearby Bristol and rationing of World War II.

Their son and only child (William) Duncan Ogilvie was born 1 November 1940 in their home in Dundry. His christening was about midday on Sunday 24 November in St James' Presbyterian Church in Bristol. That evening 148 long-range bombers of Germany's Luftflotte 3 bombed Bristol,[54] the church was never to be used again. The church tower remains but the nave is now an office block just south of Bristol bus station.

Lawrence was a member of the World War II Dundry Home Guard and the East Dundry fire-watching team. His duties, with his education and access to a typist, included the publishing of the responsibilities and shifts.

He was a founding member and a chairman of the Friends of the Bristol Art Gallery, giving the Jacob Epstein bronze Kathlene to the gallery. He was on the founding committee of Bristol's Arnolfini Gallery. Ogilvie and his wife were keen watercolour artists, and together formed a collection of 1940s and 1950s modern art.[55]

Lawrence broke his hip when he fell in his East Dundry garden: the surgeons made a mistake during his operation, moving him after a second operation non-compos mentis to Winford hospital where he died months later on 16 April 1980. His wife Doris had died of colon cancer in their East Dundry home in September 1965 with him and their son Duncan working in the garden. Duncan had four children Karen, Justin, Nicola and David.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lawrence Ogilvie. |

- Newsletter of the Federation of British Plant Pathologists No 6, Winter 1980, pages 47-48 Obituary notices: Lawrence Ogilvie by H Croxall

- Nature number 2997, 9 April 1927, page 528

- Annual reports of the Bermuda Department of Agriculture 1923-26

- Page 4 of the January 1929 Royal Botanic Society of London: Quarterly Summary

- Ogilvie, Lawrence (1928). "A Transmissible Virus Disease of the Easter Lily". Annals of Applied Biology. 15 (4): 540–562. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1928.tb07776.x.

- October 1968 Monthly Bulletin of the Bermuda Department of Agriculture and Fisheries article by Lawrence Ogilvie

- Kosmix.com

- Aberdeen Grammar School "Excellence" medals "EX Laurentio Ogilvie III Class MCMXIII" and "Ex Laurentio Ogilvie V Class MCMXV"

- The Garden magazine July 1919

- Transactions of the British Mycological Society Volume IX part III, pages 167-182, 31 March 1924 Observations on the "Slime Fluxes" of trees Lawrence Ogilvie

- Ogilvie, Lawrence (1924). "Observations on the "slime-fluxes" of trees". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 9 (3): 167–182. doi:10.1016/S0007-1536(24)80019-0.

- 978-0-11-240423-1

- Bulletin of Entomological Research Volume XVIII part 3, February 1928 pages 289-290 and plate XIII Methods employed in breeding Opius Humilis, Silv., a parasite of the Mediterranean fruit-fly (Ceratitis Capitata, Wied) L Ogilvie Bermuda Department of Agriculture

- Bulletin of Entomological Research

- Sciencedirect.com

- Jstor.com

- Fungus Diseases of Tropical Crops Paul Holliday

- Page 223 of 22 September 1928 The Gardeners' Chronicle

- Articles by A Grove on page 82 of the 2 February 1929 The Gardeners' Chronicle and page 10 of the 6 July 1929 issue

- The Lily Year Book 1957 pages 45 to 59

- Digitalcommons.unl.edu

- Jstor.org

- Cambridge University: entomological collections received.

- The Insects of Bermuda by Lawrence Ogilvie, published 1928 by the Department of Agriculture, Bermuda

- FCLA.edu

- Foreword by M. Cohen, Director of the British Plant Pathology laboratory: page iii of the 1969 sixth edition of the HMSO Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food's Diseases of Vegetables SBN 11-240423-5

- Willow diseases. Wringtonsomerset.org.uk

- The Annals of Applied Biology Volume XXVI, number 2, pages 279-297, May 1939 Lettuce mosaic G C Ainsworth and L Ogilvie

- Journal of Pomology and Horticultural Science Volume XI, no 3, pages 205-213, September 1933 Canker and die-back of apples associated with Valsa Ambiens L Ogilvie

- Journal of Pomology and Horticultural Science Volume XIII, no 2, pages 140-148, June 1935 The fungus flora of apple twigs and branches and its relation to apple fruit spots L Ogilvie

- Annual Report of the Long Ashton Research Station 1933 The effect of Formalin on potato "sickness" L Ogilvie

- Transactions of the British Mycological Society Volume XXII, parts III and IV, 1939, pages 308-9 Vegetable disease investigations at Long Ashton L Ogilvie and C J Hickman

- Transactions of the British Mycological Society Volume XXIII, part II 1939 Root rot of hardy vegetables L Ogilvie

- Nature volume 160-page 96, 19 July 1947 Occurrence of Botrytis Fabæ Sardiña in England L Ogilvie and M Munro

- 1946 Annual Report of the Agricultural and Horticultural Research Station, Long Ashton, Bristol [England] Chocolate Spot of field beans in the south west L Ogilvie and M Munro

- Six editions (each edition revised) July 1941-1969 of the British Ministry of Agriculture's 100-page Bulletin 123: Diseases of Vegetables by Lawrence Ogilvie. The first edition was expanded from Ogilvie's Vegetable Diseases: a brief summary Bulletin 68 1935.

- (British) National Agricultural Advisory Service Quarterly Review Volume XIV, Winter 1962, number 58 Relation of disease control to successful continuous cereal growing L Ogilvie and I G Thorpe

- 6th Commonwealth Mycological Conference, London 1960 Black Rust of wheat: co-operative investigations in western Europe and northern Africa L Ogilvie and I G Thorpe

- Science Progress Volume XLIX number 194, April 1961 pages 209-227 New light on epidemics of Black Stem Rust of wheat L Ogilvie and I G Thorpe

- 2nd European Colloquium on Black Rust of Cereals, Madrid April 1961 Studies of Black Rust Epidemiology in England L Ogilvie and I G Thorpe

- International Cereal Rust Conferences June and July 1964 Black Stem Rust of wheat in Great Britain L Ogilvie and I G Thorpe

- Jstor.org

- Plant Pathology volume 4, number 4, December 1955, pages 111-113 Effect of ley grasses on the carry-over of Take-All Valerie M Wehrle and L Ogilvie

- Sciencedirect.com

- BSPP.org.uk

- Sciencedirect.com

- HBCI.com Archived 9 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Hollings, M. (1958). "Anemone Brown Ring?a Virus Disease". Plant Pathology. 7 (3): 95–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.1958.tb00839.x.

- Report of the 13th International Horticultural Congress, 1952: Recent developments in vegetable diseases in Great Britain Lawrence Ogilvie

- Plant Pathology Volume 2, number 4, December 1954 New or uncommon plant diseases and pests in England and Wales: "Net blotch" of field and broad beans Moira C D Justham and L Ogilvie

- "The British Mycological Society".

- "Home".

- Volume LV, December 2009 pages 21-22 of The Journal of the Barbados Museum & Historical Society

- Pages 84-86 of 978-0-946771-89-9 Blitz over Britain by Edwin Webb and John Duncan

- Leicestergaleries.com