Livius Andronicus

Lucius Livius Andronicus (/ˈlɪviəs/; c. 284 – c. 205 BC)[1] was a Greco-Roman dramatist and epic poet of the Old Latin period. He began as an educator in the service of a noble family at Rome by translating Greek works into Latin, including Homer's Odyssey.[2] They were meant at first as educational devices in the school he founded. He wrote works for the stage—both tragedies and comedies—which are regarded as the first dramatic works written in the Latin language of ancient Rome. His comedies were based on Greek New Comedy and featured characters in Greek costume. Thus, the Romans referred to this new genre by the term comoedia palliata (fabula palliata). The Roman biographer Suetonius later coined the term "half-Greek" of Livius and Ennius (referring to their genre, not their ethnic backgrounds).[3] The genre was imitated by the next dramatists to follow in Andronicus' footsteps and on that account he is regarded as the father of Roman drama and of Latin literature in general; that is, he was the first man of letters to write in Latin.[4] Varro, Cicero, and Horace, all men of letters during the subsequent Classical Latin period, considered Livius Andronicus to have been the originator of Latin literature. He is the earliest Roman poet whose name is known.[5]

Lucius Livius Andronicus | |

|---|---|

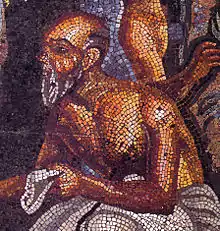

Detail of a poet giving directions from a theatrical scene. Roman mosaic from the tablinum Casa del Poeta tragico (VI 8, 3–5) in Pompeii. Naples National Archaeological Museum. | |

| Born | c. 284 BC Tarentum |

| Died | c. 205 BC Rome |

| Occupation | writer; playwright; poet |

| Language | Latin |

| Notable works | Odyssey |

Biography

Name

In ancient sources, Livius Andronicus is either given that name or is simply called Livius. Andronicus is the Latinization of a Greek name, which was held by a number of Greek historical figures of the period. It is generally considered that Andronicus came from his Greek name and that Livius, a name originally local to Latium, was the gentilicium, the family name, of his patron (patronus). His career at Rome was launched from servitude and he became a freedman (libertus) by the grace of his master, one of the Livia gens. The praenomen Lucius is given by Aulus Gellius[6] and Cassiodorus.[7]

Dates

Livius' dates are based mainly on Cicero[8][9] and Livy.[10] Cicero says, "This Livius exhibited his first performance at Rome in the Consulship of M. Tuditanus, and C. Clodius the son of Caecus, the year before Ennius was born," that is, in 240 BC. Cicero goes on to relate the point of view of Accius, that Livius was captured from Tarentum in 209, and produced a play in 197. Cicero disagrees with this view on the grounds that it would make Livius younger than Plautus and Naevius, though he was supposed to have been the first to produce a play. Livy says, "The pontiffs also decreed that three bands of maidens, each consisting of nine, should go through the city singing a hymn. This hymn [the parthenion) was composed by the poet, Livius." This action was taken to expiate the gods after a series of evil portents in the consulship of "C. Claudius Nero for the first time, M. Livius for the second;" that is, in 207. Only the dates of 240 and 207 seem exempt from controversy.[11]

Events

Jerome has some additional detail that tends to support the capture at Tarentum and enslavement. His entry for the year of Abraham 1829, the second year of the 148th Olympiad (186/185 BC), of his Chronicon, reads

Titus Livius tragoediarum scriptor clarus habetur, qui ob ingenii meritum a Livio Salinatore, cuius liberos erudiebat, libertate donatus est.

Titus Livius, author of tragedies, is held to be outstanding. He was given liberty by Livius Salinator, whose children he was educating, by merit of his intelligence.

Jerome is the only author to name him Titus. The passage is ambiguous concerning the events actually happening in Olympiad 148; Andronicus could have been being given liberty or simply have been being honoured, having been liberated long ago. Livius Salinator might be Gaius Livius Salinator, his father Marcus Livius Salinator, or his grandfather Marcus. If Jerome means that the liberation took place in 186, then he seems to be following Accius' view, which might have been presented in the missing portions of Suetonius' de Poetis and read by Jerome.[12] The passage is not conclusive about anything. However, the mixed name of Livius and his being associated with Salinator suggests that he was captured at the first fall of Tarentum in 272, sold to the first Marcus Livius Salinator, tutored the second and was set free to have an independent career when the task was complete.

Works

Odusia

Livius made a translation of the Odyssey, entitled the Odusia in Latin, for his classes in Saturnian verse. All that survives is parts of 46 scattered lines from 17 books of the Greek 24-book epic. In some lines, he translates literally, though in others more freely.[5] His translation of the Odyssey had a great historical importance. Livius' translation made this fundamental Greek text accessible to Romans, and advanced literary culture in Latin. This project was one of the first examples of translation as an artistic process; the work was to be enjoyed on its own, and Livius strove to preserve the artistic quality of the original. Since there was no tradition of epic in Italy before him, Livius must have faced enormous problems. For example, he used archaising forms to make his language more solemn and intense. His innovations would be important in the history of Latin poetry.[11]

In the fragments we have, it is clear that Livius had a desire to remain faithful to the original and to be clear, while having to alter untranslatable phrases and ideas. For example, the phrase "equal to the gods", which would have been unacceptable to Romans, was changed to "summus adprimus", "greatest and of first rank". Also, early Roman poetry made use of pathos, expressive force, and dramatic tension, so Livius interprets Homer with a mind to these ideas as well.[13] In general, Livius did not make arbitrary changes to the text; rather, he attempted to remain faithful to Homer and to the Latin language.[14]

Plays

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto.jpg.webp)

Livius' first play, according to Cicero, was staged in 240. Livy tells us that Livius was the first to create a play with a plot. One story says that after straining his voice, Livius, who was also an actor, was the first to leave the singing to singers and limited the actors to dialogue.

His dramatic works were written in the iambic senarius and trochaic septenarius. They included both lyric passages (cantica) and dialogue (diverbia). His dramatic works had large element of solos for chief actor, often himself. It is not known whether he had a chorus. These dramatic works of Livius Andronicus were consistent with Greek requirements of drama and probably had Greek models, and we have no more than 60 fragments, as quoted in other authors.

The titles of his known tragedies are Achilles, Aegisthus, Aiax Mastigophorus (Ajax with the Whip), Andromeda, Antiopa, Danae, Equus Troianus, Hermiona, and Tereus.

Two titles of his comedies are certain, Gladiolus and Ludius, though the third, Virgo, is probably corrupt. They were all composed on the model of Greek New Comedy, adapting stories from the Greek. The Romans called this sort of adaptation of comedy by Livius and his immediate successors fabulae palliatae, or comoedia palliata, named from the pallium, or short cloak, worn by the actors.[15] Of Andronicus' palliata we have 6 fragments of 1 verse each and 1 title, Gladiolus, (Little Saber).

The hymn

According to Livy,[10] Livius also composed a hymn for a chorus of 27 girls in honour of Juno to be performed in public as part of religious ceremonies in 207. Because of the success of this hymn, Livius received public honours when his professional organization, the collegium scribarum histrionumque was installed in the Temple of Minerva on the Aventine. Actors and writers would gather here and offer gifts.

Notes

- "Lucius Livius Andronicus". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47).

- Monroe, Paul (1902). "Selections from the Lives of Eminent Grammarians, by Suetonius". Source book of the history of education for the Greek and Roman period. New York, London: Macmillan Co. pp. 349–350.

...for the earliest men of learning, who were both poets and orators, may be considered as half-Greek: I speak of Livius and Ennius, who are acknowledged to have taught both languages as well at Rome as in foreign parts.

- Livingston (2004, xi).

- Rose (1954, 21).

- Aulus Gellius. "Book 18, Chapter 9". Attic Nights.

For in the library at Patrae I found a manuscript of Livius Andronicus ....

- Livingston (2004, xii).

- Brutus 18.72–74.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. "Section 50". De Senectute.

I myself [ Cato the Elder ] saw Livius Andronicus when he was an old man, who, though he brought out a play in the consulship of Cento and Tuditanus [240 BC], six years before I was born, yet continued to live until I was a young man.

- 27.37.7

- Conte (1994, 40).

- Livingston, Ivy J. (2004). A linguistic commentary on Livius Andronicus. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francos Group. p. xii.

- Conte (1994, 41).

- von Albrecht (1997, 115)

- Ashmore (1908, 14)

Further reading

- Albrecht, Michael von. (1997). A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius. With special regard to its influence on world literature. 2 vols. Revised by Gareth L. Schmeling and Michael von Albrecht. Mnemosyne Supplement 165. Leiden: Brill.

- Boyle, A. J., ed. (1993). Roman Epic. London and New York: Routledge.

- Brockett, Oscar G.; Hildy, Franklin J. (2003). History of the Theatre (Ninth International ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0205410507.

- Büchner, Karl. (1979). "Livius Andronicus und die erste künstlerische Übersetzung der europäischen Kultur." Symbolae Osloenses 54: 37–70.

- Conte, Gian Biagio; Solodow, Joseph B. (Translator) (1994). Latin Literature: A History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Erasmi, G. (1979). "The Saturnian and Livius Andronicus." Glotta, 57(1/2), 125–149.

- Farrell, Joseph. (2005). "The Origins and Essence of Roman Epic." In A Companion to Ancient Epic. Edited by John Miles Foley, 417–428. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World, Literature and Culture. Malden: Blackwell.

- Fantham, Elaine. (1989). "The Growth of Literature and Criticism at Rome." In The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Vol. 1, Classical Ccriticism. Edited by George A. Kennedy, 220–244. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Horsfall, N. (1976). "The Collegium Poetarum." Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, (23), 79–95.

- Kearns, J. (1990). "Semnoths and Dialect Gloss in the Odussia of Livius Andronicus." The American Journal of Philology, 111(1), 40–52.

- Rose, H. J. (1954). A Handbook of Latin Literature from the Earliest Times to the Death of St. Augustine. London: Methuen.

- Sciarrino, E. (2006). "The Introduction of Epic in Rome: Cultural Thefts and Social Contests." Arethusa 39(3), 449–469. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Sheets, G. A. (1981). "The Dialect Gloss, Hellenistic Poetics and Livius Andronicus." The American Journal of Philology, 102(1), 58–78.

- Waszink, J. (1960). "Tradition and Personal Achievement in Early Latin Literature." Mnemosyne, 13(1), fourth series, 16–33.

- Wright, John. (1974). Dancing in Chains: The Stylistic Unity of the comoedia palliata. Papers and Monographs of the American Academy in Rome 25. Rome: American Academy in Rome.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Livius Andronicus. |

| Library resources about Livius Andronicus |

| By Livius Andronicus |

|---|

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Livius Andronicus

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Livius Andronicus- "Livius Andronicus". Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- Lucius Livius Andronicus PHI Latin Texts