Louis Lépine

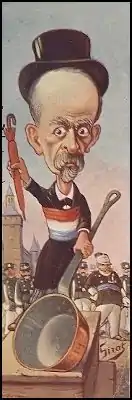

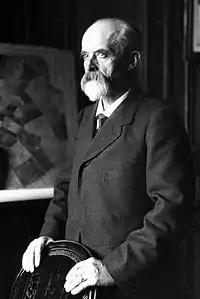

Louis Jean-Baptiste Lépine (1846 - 1933) was a lawyer, politician and inventor who was Préfet de Police with the Paris Police Prefecture from 1893 to 1897 and again from 1899 to 1913. He earned the nickname of "The Little Man with the Big Stick" for his skill in handling large Parisian crowds.[1] He was responsible for the modernisation of the French Police Force. Under Lépine the study of forensic science as a tool of detection became standard practise.[2]

Louis Lépine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Préfet de Police | |

| In office 11 July 1893 – 14 October 1897 | |

| Preceded by | Henri-Auguste Lozé |

| Succeeded by | Charles Blanc |

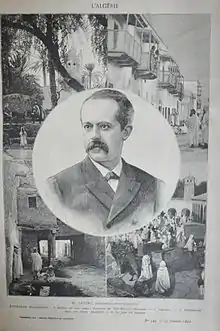

| Governor General of Algeria | |

| In office 1 October 1897 – 26 July 1898 | |

| Preceded by | Henri-Auguste Lozé |

| Succeeded by | Édouard Laferrière |

| Préfet de Police | |

| In office June 23, 1899 – March 29, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Blanc |

| Succeeded by | Célestin Hennion |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 6, 1846 Lyon |

| Died | November 9, 1933 (aged 87) Paris |

| Relations | Raphaël Lépine |

| Awards | Médaille militaire |

| Nickname(s) | The Little Man with the Big Stick, The prefect of the street |

Early life

Louis Lépine studied law in his home city of Lyon and in Paris and Heidelberg. He served with distinction in the French Army during the Franco-Prussian War from 1870 to 1871. Serving as a sergeant major at Belfort in the Alsace region, his unit was besieged and continually attacked by the Prussians. It surrendered only after the hostilities had ceased.

Lépine was awarded the Médaille militaire for his bravery. He then embarked on a career as a lawyer and public administrator, a successful career that took in provincial postings that included deputy prefect of Lapalisse, Montbrison, Langres and Fontainebleau and then prefect of the Indres, the Loire and Seine-et-Oise.[3]

The 1893 student uprising in Paris

In 1893 Lépine became prefect of police of the Seine (Paris) at a time when Paris and indeed France was politically volatile. The perceived failure of the previous Prefect Henri-Auguste Lozé to quell serious student riots in 1893 resulted in Lépine’s appointment. The riots that had taken place arose out of a trivial incident involving the arrest of an actress Sarah Brown, a student called Nuger and a confrontation with a policeman, the consequence of which was the death of Nuger. On the following Monday, 1,000 demonstrators marched onto the Chamber of Deputies, determined to be provided with an adequate explanation. The Deputies summarily retreated and by the evening a further 1,000 students were outside and by now the mood of the demonstrators had turned hostile. At the end of the day barricades were erected around the district of the Boulevard Saint-Germain.[4]

The police had lost control of the situation and the National Guard was called in to regain control. There followed several days of bloodshed as several important workers’ organisations sided with the so-called students. Within five days of the arrest of Sarah Brown, the students were submerged within a violent mob that was ready to fight for control of Paris.[5]

The French Republic seemed in danger and reacted with extreme force with an estimated 20,000 troops deployed to quell the uprising. It was against this backdrop that Louis Lépine succeeded to the Prefecture of Police for Paris with a reputation as a disciplinarian prepared to use the "big stick" to keep Paris under control. Lépine’s tactics were to allow the various factions to march through Paris but he used skilful and innovative tactics of crowd control to make sure that the various factions were, in effect kept apart, arriving at the planned rendezvous in stages.

The modernisation of the police

Lépine is credited as the founder of modern French policing.[6] At the time of his first tenure the police had become renowned for corruption and low standards, trust between the police and the public was very low. Lépine recognised that if France was not to relapse into military government the relationship between the civil police and the public had to change to become one of mutual trust. The assassination in Lyon in June 1894 of President Carnot, the 5th President of the Republic was the impetus for Lépine to introduce measures to overhaul policing in France. Thus he set an agenda of reform beginning by carefully codified police procedures and regulations, improving the professional quality of the police force with the introduction of examinations and promotions and by introducing forensic science into the work of the detective. It was during his time as prefect of police that fingerprinting became established as a method of identification. The examinations for police that he instituted were very thorough: the tests for example included determining methods of forgery and examining lock components involved in a burglary so as to tell if a lock had been picked. As befits his training as a lawyer, his was the first prefecture to introduce criminology into policing and to examine the psychology of criminals.[6]

Amongst his other innovations, he introduced the white stick for directing traffic and established the river-boat brigade and armed police bicycle units. He installed a series of 500 telephone warning boxes to alert the public and fire services to fire, and he began the reorganisation of traffic movements within Paris by introducing one-way systems and roundabouts.

The Dreyfus Affair

.

.

Lépine succeeded Jules Cambon as Governor-General of Algeria in September 1897, serving less than a year in the post. He was recalled to Paris as the Dreyfus Affair began to unravel the Third Republic. In 1894 Alfred Dreyfus, an Alsatian of Jewish descent, had been found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly having communicated French military secrets to Germany. Lépine had officiated at the original trial. When two years later it became apparent that Dreyfus was innocent, as another culprit had been found, a retrial was ordered. The military court once again found Dreyfus guilty on the basis of false documents fabricated by French counter-intelligence officers. There was widespread dissent against the proceedings that culminated in a vehement public protestation from Émile Zola, the novelist. Another retrial was subsequently ordered, and this time Dreyfus was freed, although he was not exonerated until 1906.

France seemed to be at the start of civil unrest in 1899, and once again Louis Lépine was recalled to help ease the situation. Again and again Paris appeared to be on the point of violent protestations, but through wise diplomacy and carefully organised policing, Lépine managed to avoid the worst of times. He attempted to limit the role of the army as a force of internal order by handling most situations with police and gendarmerie alone. During these febrile times France faced the possibility of a military government and whilst there were occasions when Lépine required military assistance to control demonstrations it is credit to his reforms that these were rare and that the gendamerie largely controlled the civil strife.[7]

Préfet de police 1900-1913

The final decade of Lépine's tenure as préfet de police proved not to be as politically dramatic as his early years. He continued in the task of reforming the police force intent on creating a modern police force to meet the needs of Paris and France.

In 1900 he founded the Musée des Collections Historiques de la Préfecture de Police in response to the Exposition Universelle. The museum concentrated on the forensic science of policing and has gradually grown through subsequent years. It now contains evidence, photographs, letters, memorabilia, and drawings that reflect major events in the history of France (including conspiracies and arrests), famous criminal cases and characters, prisons, and daily life in the capital such as traffic and hygiene.

Lépine's realisation that the police required the support of the people to be effective was the catalyst to continue reform almost to the end of his tenure. In 1912 he founded a detective training school based on modern forensic methods of training. This was a lasting legacy and was a methodology admired and copied by other countries.[8][note 1]

Great Flood of Paris

Lépine faced a number of high-profile events and crimes during this period of office. Each he handled with his usual decisiveness and belief in his own authority.

In late January 1910, following months of high rainfall, the River Seine in Paris flooded the French capital, reaching a maximum height of 8.62 metres. The Great Flood of Paris as it is colloquially known caused extensive damage and forced thousands out of their homes. The infrastructure within Paris came close to destruction and there were major concerns for public health. France mobilised to save its capital. Lépine whose office included public health proved as tough and authoritarian as he had been on policing matters. In the flood's aftermath he established new procedures to address the problems of flooding. The instructions explained the importance of chemical cleansing and institutionalized the growing medical consensus about the causes of water borne diseases that had been controversial just a few years earlier.[9][10]

Armand Fallières, president of the French Republic and Lépine worked closely with each other at the outset of the flood as they were concerned that Paris could dissolve into major disorder if the government response was seen to be ineffectual. In the event major disturbances were largely avoided. Throughout the crisis Lépine was a visible presence attempting to lead from the front by reassuring Parisians that order would be maintained alongside the humanitarian efforts that were taking place.[10]

The theft of the Mona Lisa

The theft on August 22, 1911 of the Mona Lisa from the Musée du Louvre was more of an embarrassment to Lépine although initially he acted with his usual decisiveness ordering the museum to be closed for a week whilst forensic analysis was carried out. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire came under suspicion; he was arrested and put in jail. Apollinaire tried to implicate his friend Pablo Picasso, who was also brought in for questioning, but both were later exonerated. The real thief was Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia an Italian wishing to return it to Italy. He was caught with the painting in Florence two years later when he attempted to sell it to the directors of the Uffizi Gallery.[11]

The defeat of the Bonnot Band

One of Lépine's last successes was the capture and destruction of the notorious Bonnot Gang (La Bande à Bonnot), an anarchist criminal group that operated in France and Belgium during the Belle Époque, from 1911 to 1912. In 1910 Lépine had instigated La Brigade Criminelle a dedicated unit of specialist law enforcers whose purpose was to gather intelligence and take direct action against high-profile criminals.[12] La Brigade Criminelles reputation was established after they were instrumental under Lépine's leadership in destroying the Bonnot Gang. Lépine ordered the leader of the gang Jules Bonnot to be captured on discovering his whereabouts in Paris. The operation began badly when three of his officers were shot during the operation. Lépine then ordered the building to be blown up with dynamite and reputedly administered the final debilitating shot to the head of Jules Bonnot.[12]

Concours Lépine

The Exposition Universelle provided the catalyst for innovation and Lépine decided to create a competition for inventors that continues to be held annually to this day. It was originally intended to encourage small toy and hardware manufacturers, but over the years it has grown into an annual event that includes a multitude of innovative ideas. The 114th edition of the Concours Lepine Show took place over two weeks in April and May 2015 at the Foire de Paris in the Porte de Versailles.

Louis Lépine retired in 1913 and was succeeded by Célestin Hennion.In the same year he was elected a member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques.

He published his memoirs in 1929,[3] four years before his death in 1933. He was the brother of the Professor Raphaël Lépine, the pioneering physiologist.

Bibliography

- Louis Lépine Mes Souvenirs, Payot, Paris (1929) (in French)

- Jacques Porot, Louis Lépine : préfet de police-témoin de son temps : 1846-1933, Paris, 1994. (in French)

- Berlière, Jean-Marc (1993). Le Préfet Lépine, vers la naissance de la police moderne. Paris: Denoel. (in French)

Cultural references

The 4th Arrondissement of Paris contains Place Louis Lépine, the venue for a flower market and appropriately the headquarters of the Prefecture of Police (Préfecture de Police)

In 1912 the grateful City of Paris authorities commissioned Charles Pillet for a plaque bearing the likeness of Louis Lépine, a copy of which is found at the Musée Carnavalet.

Notes

- The article subtitled "M.Lépine, Head of The Police Department,Creates a School for Training Detectives" is available at https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1912/08/25/100374695.pdf New York Times August 25, 1912.

References

- "Lépine, Famous Paris Chief of Police, To Retire", The New York Times. February 25, 1913

- Jean-Marc Berlière, Le préfet Lépine : vers la naissance de la police moderne, Paris, 1993. (French)

- Louis Lépine Mes Souvenirs, Payot, Paris (1929)

- Lépine, Famous Paris Chief of Police, To Retire", The New York Times, February 25, 1913

- "Lépine, Famous Paris Chief of Police, To Retire", The New York Times, February 25, 1913

- Jean-Marc Berlière, Le préfet Lépine : vers la naissance de la police moderne, Paris, 1993.

- Berlière, J.-M., Institution policière en France sous la Troisième République, 1875-1914, University of Bourgogne, 1991 (French)

- Article in New York Times, August 25, 1912

- David S Barnes,The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth Century Struggles Against Filth and Germs, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore 2006

- Jeffrey H. Jackson, Paris Under Water: How The City of Light Survived the Great Flood of 1910, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

- "Top 25 Crimes of the Century: Stealing the Mona Lisa, 1911". Time. 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- Richard Parry, The Bonnot Gang, Rebel Press.(1987) ISBN 0-946061-04-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Lépine. |