Luis de Moscoso Alvarado

Luis de Moscoso Alvarado (1505 – 1551) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador. Luis de Moscoso Alvarado assumed command of Hernando De Soto's expedition upon the latter's death.

Luis de Moscoso Alvarado | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1505 |

| Died | 1551 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | explorer and conquistador |

Early life

Luis de Moscoso Alvarado was born in Badajoz, Spain, to Alonso Hernández Diosdado Mosquera de Moscoso and Isabel de Alvarado. De Moscoso had two brothers, Juan de Alvarado and Cristóbal de Mosquera. His uncle was the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, who had excelled in the conquests of Mexico and Central America.[1]

Career

Expeditions with Pedro de Alvarado

Alvarado accompanied his uncle on expeditions to the Americas, where he participated in the conquest of present-day Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador.[1] In 1530 Pedro sent Luis to El Salvador to set up a colony in the East of the region. On May 8, 1530 Alvarado founded the town of San Miguel de la Frontera in modern San Miguel Department. In addition, Alvarado founded San Miguel with about 120 Spanish cavalry, as well as with infantry and Indian auxiliaries, crossed the Lempa River and founded San Miguel on 21 November 1530.[2]

In 1534, he traveled to Peru with his uncle on an expedition through what is now Ecuador. As Alvarado explored the area, he and Pedro discovered several tribes in the Manabí Province.[1]

Expeditions with Hernando de Soto

After returning to Peru,[1] Alvarado and his two brothers decided to work with Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto.

Soto and Alvarado returned to Spain in 1536 due to a discussion broke out between Diego de Almagro and Francisco Pizarro. In Spain, apparently, Alvarado made improper use of the wealth he had acquired in Peru, forcing his return to the Americas to recover it. He left the Spanish port of Sanlucar de Barrameda with de Soto's army, leading one of the expedition's seven ships.

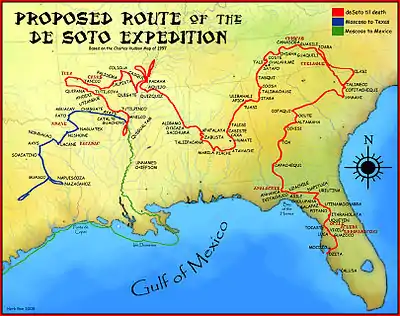

On April 7, 1538 the expedition reached Florida's coast. Alvarado obtained the title of "maestre de campo" (field commander) and kept this title until March 1541, when the group was attacked by the Chickasaw Native American tribe, which caused the death of twelve Spaniards and many of the horses that participated in the expedition. The attack was, apparently (and mainly), the result of a misunderstanding between Alvarado and the tribe. De Soto died on May 21, 1542, in what became Arkansas, leaving Moscoso as the leader of the expedition, in the position of commander. After consulting with the other leaders, Moscoso decided to abandon the mission to found a colony and take the expedition to the modern-day Mexico.[1][4]

Own expeditions

Moscoso and his army marched west, reaching northwest Louisiana and Texas. They encountered with Caddoan Mississippian peoples along the way, but lacked interpreters to communicate with them and eventually ran into territory too dry for maize farming and too thinly populated to sustain themselves by stealing food from the local populations. The expedition promptly backtracked to Guachoya on the Mississippi River.[1][4]

Over the winter of 1542-1543 they built "seven bergantines, or pinnaces, with which to seek a water route to Mexico". On July 2, 1543, Just over half of the members of the expedition (322 people) had survived and they traveled to the Mississippi River. Along the way they had a running three day battle with the chiefdom of "Quigualtam", in which more men were lost. Alvarado's expeditionary group eventually made it to the Gulf Coast on July 16th, 1543, and began sailing westward along the Louisiana and Texas shores. The group probably also found some of Texas' bays (possibly Matagorda Bay, Corpus Christi Bay or Aransas Bay) before finally arriving the Pánuco River, and then traveling on to Mexico City.[5]

There Moscoso wrote two letters to Charles V, the king of Castile at the time, although these letters explained little about the expedition. Later, Moscoso began to work for the viceroy of New Spain Antonio de Mendoza, whom he accompanied in his traveled to Peru in 1550. It was there where Moscoso died in 1551.

Personal life

After sending the letters to the King of Spain, Moscoso Alvarado married Leonor in Mexico City. Leonor was daughter of the Alvarado's uncle Juan de Alvarado (the brother of Pedro de Alvarado).[1]

Legacy

Mosca Pass, in the Alamosa County´s Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, is named after Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado, who may have arrived in the area in an exploration team in 1542.[6]

References

- Robert S. Weddle. Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "," Luis de Moscoso Alvarado. Posted on Handbook of Texas Online. Accessdate on May 8, 2010.

- Vallejo García-Hevia 2008, pp. 207, 380.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 353-379.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 380-392.

- Ferril, William (1911). Sketches of Colorado: being an analytical summary and biographical history of the State of Colorado as portrayed in the lives of the pioneers, the founders, the builders, the statesmen, and the prominent and progressive citizens who helped in the development and history making of Colorado, Volume 1. Western Press Bureau Co. p. 10. Retrieved 2014-08-21.

Bibliography

- S. Weddle, Robert. Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "," Luis de Moscoso Alvarado. Posted on Handbook of Texas Online. Accessdate on May 8, 2010.

- Vallejo García-Hevia (2008). Juicio a un conquistador: Pedro de Alvarado: su proceso de residencia en Guatemala (1536–1538) (in Spanish). Volume 1. Madrid, Spain: Marcial Pons, Ediciones de Historia. ISBN 978-84-96467-68-2. OCLC 745512698.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- Ferril, William (1911). Sketches of Colorado: being an analytical summary and biographical history of the State of Colorado as portrayed in the lives of the pioneers, the founders, the builders, the statesmen, and the prominent and progressive citizens who helped in the development and history making of Colorado, Volume 1. Publisher in Western Press Bureau Co. Page 10. Accessdate on 2014-08-21.