Mössbauer effect

The Mössbauer effect, or recoilless nuclear resonance fluorescence, is a physical phenomenon discovered by Rudolf Mössbauer in 1958. It involves the resonant and recoil-free emission and absorption of gamma radiation by atomic nuclei bound in a solid. Its main application is in Mössbauer spectroscopy.

In the Mössbauer effect, a narrow resonance for nuclear gamma emission and absorption results from the momentum of recoil being delivered to a surrounding crystal lattice rather than to the emitting or absorbing nucleus alone. When this occurs, no gamma energy is lost to the kinetic energy of recoiling nuclei at either the emitting or absorbing end of a gamma transition: emission and absorption occur at the same energy, resulting in strong, resonant absorption.

History

The emission and absorption of X-rays by gases had been observed previously, and it was expected that a similar phenomenon would be found for gamma rays, which are created by nuclear transitions (as opposed to X-rays, which are typically produced by electronic transitions). However, attempts to observe nuclear resonance produced by gamma-rays in gases failed due to energy being lost to recoil, preventing resonance (the Doppler effect also broadens the gamma-ray spectrum). Mössbauer was able to observe resonance in nuclei of solid iridium, which raised the question of why gamma-ray resonance was possible in solids, but not in gases. Mössbauer proposed that, for the case of atoms bound into a solid, under certain circumstances a fraction of the nuclear events could occur essentially without recoil. He attributed the observed resonance to this recoil-free fraction of nuclear events.

The Mössbauer effect was one of the last major discoveries in physics to be originally reported in the German language. The first report in English was a letter describing a repetition of the experiment.[1]

The discovery was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1961 together with Robert Hofstadter's research of electron scattering in atomic nuclei.

Description

The Mössbauer Effect is a process in which a nucleus emits or absorbs gamma rays without loss of energy to a nuclear recoil. It was discovered by the German physicist Rudolf L. Mössbauer in 1958 and has proved to be remarkably useful for basic research in physics and chemistry. It has been used, for instance, in precisely measuring small energy changes in nuclei, atoms, and crystals induced by electrical, magnetic, or gravitational fields. In a transition of a nucleus from a higher to a lower energy state with accompanying emission of gamma rays, the emission generally causes the nucleus to recoil, and this takes energy from the emitted gamma rays. Thus the gamma rays do not have sufficient energy to excite a target nucleus to be examined. However, Mössbauer discovered that it is possible to have transitions in which the recoil is absorbed by a whole crystal in which the emitting nucleus is bound. Under these circumstances, the energy that goes into the recoil is a negligible portion of the energy of the transition. Therefore, the emitted gamma rays carry virtually all of the energy liberated by the nuclear transition. The gamma rays thus are able to induce a reverse transition, under similar conditions of negligible recoil, in a target nucleus of the same material as the emitter but in a lower energy state. In general, gamma rays are produced by nuclear transitions from an unstable high-energy state to a stable low-energy state. The energy of the emitted gamma ray corresponds to the energy of the nuclear transition, minus an amount of energy that is lost as recoil to the emitting atom. If the lost recoil energy is small compared with the energy linewidth of the nuclear transition, then the gamma ray energy still corresponds to the energy of the nuclear transition, and the gamma ray can be absorbed by a second atom of the same type as the first. This emission and subsequent absorption is called resonant fluorescence. Additional recoil energy is also lost during absorption, so in order for resonance to occur the recoil energy must actually be less than half the linewidth for the corresponding nuclear transition.

The amount of energy in the recoiling body (ER) can be found from momentum conservation:

where PR is the momentum of the recoiling matter, and Pγ the momentum of the gamma ray. Substituting energy into the equation gives:

where ER (0.002 eV for 57

Fe

) is the energy lost as recoil, Eγ is the energy of the gamma ray (14.4 keV for 57

Fe

), M (56.9354 u for 57

Fe

) is the mass of the emitting or absorbing body, and c is the speed of light.[2] In the case of a gas the emitting and absorbing bodies are atoms, so the mass is relatively small, resulting in a large recoil energy, which prevents resonance. (Note that the same equation applies for recoil energy losses in x-rays, but the photon energy is much less, resulting in a lower energy loss, which is why gas-phase resonance could be observed with x-rays.)

In a solid, the nuclei are bound to the lattice and do not recoil in the same way as in a gas. The lattice as a whole recoils but the recoil energy is negligible because the M in the above equation is the mass of the whole lattice. However, the energy in a decay can be taken up or supplied by lattice vibrations. The energy of these vibrations is quantised in units known as phonons. The Mössbauer effect occurs because there is a finite probability of a decay occurring involving no phonons. Thus in a fraction of the nuclear events (the recoil-free fraction, given by the Lamb–Mössbauer factor), the entire crystal acts as the recoiling body, and these events are essentially recoil-free. In these cases, since the recoil energy is negligible, the emitted gamma rays have the appropriate energy and resonance can occur.

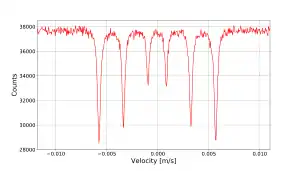

In general (depending on the half-life of the decay), gamma rays have very narrow linewidths. This means they are very sensitive to small changes in the energies of nuclear transitions. In fact, gamma rays can be used as a probe to observe the effects of interactions between a nucleus and its electrons and those of its neighbors. This is the basis for Mössbauer spectroscopy, which combines the Mössbauer effect with the Doppler effect to monitor such interactions.

Zero-phonon optical transitions, a process closely analogous to the Mössbauer effect, can be observed in lattice-bound chromophores at low temperatures.

See also

References

- Craig, P.; Dash, J.; McGuire, A.; Nagle, D.; Reiswig, R. (1959). "Nuclear Resonance Absorption of Gamma Rays in Ir191". Physical Review Letters. 3 (5): 221. Bibcode:1959PhRvL...3..221C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.3.221.

- Nave, C.R. (2005). "Mössbauer Effect in Iron-57". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

Further reading

- Mössbauer, R. L. (1958). "Kernresonanzfluoreszenz von Gammastrahlung in Ir191". Zeitschrift für Physik A (in German). 151 (2): 124–143. Bibcode:1958ZPhy..151..124M. doi:10.1007/BF01344210.

- Frauenfelder, H. (1962). The Mössbauer Effect. W. A. Benjamin. LCCN 61018181.

- Eyges, L. (1965). "Physics of the Mössbauer Effect". American Journal of Physics. 33 (10): 790–802. Bibcode:1965AmJPh..33..790E. doi:10.1119/1.1970986.

- Hesse, J. (1973). "Simple Arrangement for Educational Mössbauer-Effect Measurements". American Journal of Physics. 41 (1): 127–129. Bibcode:1973AmJPh..41..127H. doi:10.1119/1.1987142.

- Ninio, F. (1973). "The Forced Harmonic Oscillator and the Zero-Phonon Transition of the Mössbauer Effect". American Journal of Physics. 41 (5): 648–649. Bibcode:1973AmJPh..41..648N. doi:10.1119/1.1987323.

- Vandergrift, G.; Fultz, B. (1998). "The Mössbauer effect explained". American Journal of Physics. 66 (7): 593–596. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..593V. doi:10.1119/1.18911.

- Encyclopedia Americana (1988) "Mossbauer Effect" Encyclopedia Americana 19: 500 ISBN 0-7172-0119-8 (set)

External links

Media related to Mössbauer effect at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mössbauer effect at Wikimedia Commons