Macbeth

Macbeth /məkˈbɛθ/, fully The Tragedy of Macbeth, is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It was probably first performed in 1606.[lower-alpha 1] It was first published in the Folio of 1623, possibly from a prompt book, and is Shakespeare's shortest tragedy.[1]

%252C_as_Macbeth_(from_'Macbeth'%252C_Act_II%252C_Scene_2)_John_Jackson_(1778%E2%80%931831)_Royal_Shakespeare_Theatre.jpg.webp)

Macbeth is a Scottish general who has been fighting for King Duncan. Three witches tell Macbeth that he will become king of Scotland. Macbeth is spurred by his ambition and his wife, and he murders Duncan and accedes to the throne. His reign is bloody and tyrannical and ended by the combined forces of Scotland and England.

Shakespeare's main source for the story was Holinshed's Chronicles, particularly its accounts of Macbeth and Macduff and Duncan, but events in the play differ extensively from events involving the historical Macbeth. Events in Shakespeare's play are usually associated with Henry Garnet and the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.[2]

In theatre Macbeth has been associated with a curse. People have avoided speaking its title, calling it "The Scottish Play". However, it has attracted some of the most renowned actors to the leading roles and has been adapted for multifarious other media. It has been continuously in production since the 1660s.[3]

Characters

- Duncan – king of Scotland

- Malcolm – Duncan's elder son

- Donalbain – Duncan's younger son

- Macbeth – a general in the army of King Duncan; originally Thane of Glamis, then Thane of Cawdor, and later king of Scotland

- Lady Macbeth – Macbeth's wife, and later queen of Scotland

- Banquo – Macbeth's friend and a general in the army of King Duncan

- Fleance – Banquo's son

- Macduff – Thane of Fife

- Lady Macduff – Macduff's wife

- Macduff's son

- Ross, Lennox, Angus, Menteith, Caithness – Scottish Thanes

- Siward – general of the English forces

- Young Siward – Siward's son

- Seyton – Macbeth's armourer

- Hecate – queen of the witches

- Three Witches

- Captain – in the Scottish army

- Three Murderers – employed by Macbeth

- Third Murderer

- Two Murderers – attack Lady Macduff

- Porter – gatekeeper at Macbeth's home

- Doctor – Lady Macbeth's doctor

- Doctor – at the English court

- Gentlewoman – Lady Macbeth's caretaker

- Lord – opposed to Macbeth

- First Apparition – armed head

- Second Apparition – bloody child

- Third Apparition – crowned child

- Attendants, Messengers, Servants, Soldiers

Plot

Act I

_Royal_Shakespeare_Theatre.jpg.webp)

Three witches resolve to meet Macbeth after the battle. Victory is reported to King Duncan. Duncan is impressed by reports of Macbeth's conduct so transfers the rebellious Thane of Cawdor's title to him. The witches meet Macbeth and Banquo. The witches prophesy to Macbeth then Banquo then vanish. Ross and Angus arrive with news that accords with that same "prophetic greeting" (1.3.78). Macbeth muses much on "the swelling act / Of the imperial theme" (1.3.130-31) before suggesting they all move on. They meet Duncan. Duncan names Malcolm (Duncan's son) heir then says he will stay with Macbeth. Macbeth sets off ahead to tell his wife. Macbeth's wife has a letter from Macbeth. She muses too on the prospect of Macbeth becoming king as prophesied. She is interrupted by a messenger then by Macbeth. She advises Macbeth that Duncan must be "provided for" (1.5.67). Duncan arrives and is received kindly. Macbeth steps out from dining with Duncan and worries about consequences of killing him. His wife allays his anxiety and he is "settled" (1.7.80).

Act II

At night Banquo broaches the witches to Macbeth. Macbeth says he "think[s] not of them" (2.1.22) but would discuss the business at a suitable time. Macbeth's wife is waiting anxiously for Macbeth to kill Duncan. Macbeth arrives and is extremely distressed. He says that he has "done the deed" (2.2.15). He has brought the daggers which he should have planted with the drugged grooms but refuses to go back. His wife takes them and stresses the importance of smearing the grooms with blood. Macduff and Lennox are met at the gate then led to Duncan's door. Macduff goes through then Macbeth and Lennox discuss the "unruly" (2.3.54) night. Macduff reappears and proclaims horror. Macbeth and Lennox go through then Macduff raises an alarm to which all convene. "Those of his chamber" (2.3.102) are blamed and killed by Macbeth. All agree to meet and discuss besides Malcolm and Donalbain (Duncan's two sons) who flee. Ross discusses the situation with an old man until Macduff arrives with news that Malcolm and Donalbain are fled and held in suspicion and that Macbeth is named king.

Act III

_Guildhall_Art_Gallery.jpg.webp)

Banquo muses on the situation. Macbeth and his wife are now king and queen and they meet Banquo then invite him to a feast. Macbeth has achieved what was prophesied for himself but disapproves of what was prophesied for Banquo (that he would "get kings, though [himself] be none" (1.3.67)). He meets two murderers therefore. They agree to kill Banquo and Fleance (Banquo's son). Macbeth and his wife discuss Banquo. Three murderers kill Banquo but Fleance escapes. Macbeth receives such news then sees Banquo's ghost sitting in his place at the feast. Macbeth reacts thereto and thereby "displace[s] the mirth" (3.4.107). He tells his wife that he will visit the witches tomorrow. Lennox questions a lord about Macduff.

Act IV

Macbeth meets the witches. They conjure apparitions to address his concerns then vanish. Macbeth learns that Macduff is in England. He has just been warned to "Beware Macduff" (4.1.70) so resolves to seize Macduff's property and slaughter his family. Ross discusses Macduff's flight with Macduff's wife then leaves her. A messenger advises Macduff's wife to flee then does so himself. Murderers enter. One of them kills her son. She flees while "crying 'Murder'" (SD 4.2.87). In England Malcolm goads Macduff to a "noble passion" (4.3.114). He is convinced thereby of Macduff's "good truth and honour" (4.3.117) so tells him that he has soldiers ready. Ross arrives and they share news including such of Macduff's slaughtered family.

Act V

A doctor and a gentlewoman observe Macbeth's wife walking and talking and apparently asleep. Military action against Macbeth begins with marches. Macbeth dismisses the news thereof and quotes the apparitions. The doctor tells Macbeth that he cannot cure Macbeth's wife. The forces marching against Macbeth all meet then move on against Macbeth. Macbeth continues to scoff at them until he is told that his wife is dead. He muses on futility and what the apparitions told him. Macduff seeks Macbeth in the field while Malcolm takes the castle. Macduff finds Macbeth. Macbeth is confident until he realises that he has misinterpreted the apparitions. His nihilism peaks but he will not yield. Macduff takes Macbeth's head to Malcolm and hails him King of Scotland. Malcolm distributes titles.

(Although Malcolm, not Fleance, is placed on the throne, the witches' prophecy concerning Banquo ("Thou shalt get kings") was known to the audience of Shakespeare's time to be true: James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England) was supposedly a descendant of Banquo.[4])

Sources

A principal source was the Daemonologie of King James, published in 1597. Daemonologie includes a news pamphlet, Newes from Scotland, which detailed the famous North Berwick Witch Trials of 1590.[6] Daemonologie was published several years before Macbeth was performed with themes and setting in a direct and comparative contrast with King James' personal experiences with witchcraft. Not only had this trial taken place in Scotland, the witches involved were recorded to have also conducted rituals with the same mannerisms as the three witches. One of the evidenced passages is referenced when the witches involved in the trial confessed to attempt the use of witchcraft to raise a tempest and sabotage the very boat King James and his queen were on board during their return trip from Denmark. This was significant as one ship sailing with King James' fleet actually sank in the storm. The three witches in Macbeth discuss the raising of winds at sea in the opening lines of Act 1 Scene 3.[7]

Macbeth has been compared with Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra. As characters, both Antony and Macbeth seek a new world, even at the cost of the old one. Both fight for a throne and have a 'nemesis' to face to achieve that throne. The nemesis for Antony is Octavius, and the nemesis for Macbeth is Banquo. At one point Macbeth even compares himself to Antony, saying "under [Banquo] / My Genius is rebuked, as it is said / Mark Antony's was by Caesar" (3.1.54-56). Both plays also contain powerful and manipulative female figures, Cleopatra and Lady Macbeth.[8] Shakespeare was probably writing both plays simultaneously.

Shakespeare assembled his story from several tales which he had found in Holinshed's Chronicles, a popular history of the British Isles, familiar to Shakespeare's contemporaries. In the Chronicles, a man named Donwald finds several of his family put to death by his king, King Duff, for dealing with witches. After being pressured by his wife, Donwald and four of his servants kill the King in his own house. In the Chronicles, Macbeth is portrayed as struggling to support the kingdom in the face of King Duncan's ineptitude. Macbeth and Banquo meet three witches who prophesy as in Shakespeare's version. Macbeth and Banquo then plot the murder of Duncan together, at Lady Macbeth's urging. Macbeth reigns for ten years before being overthrown by Macduff and Malcolm. Some scholars think that George Buchanan's Rerum Scoticarum Historia matches Shakespeare's version more closely. Buchanan's work was available to Shakespeare in Latin.[9]

Neither the Weird Sisters nor Banquo nor Lady Macbeth are mentioned in any known medieval account of Macbeth's reign, and of these only Lady Macbeth (Gruoch of Scotland) actually existed.[10] They were first mentioned in 1527, in Historia Gentis Scotorum (History of the Scottish People), a book by Scottish historian Hector Boece. Boece wanted to denigrate Macbeth and strengthen the claim of the House of Stewart to the Scottish throne.[10] He portrayed Banquo as an ancestor of the Stewart kings of Scotland, adding in a prophecy that the descendants of Banquo would be the rightful kings of Scotland. The Weird Sisters served to give a picture of King Macbeth as gaining the throne via dark and supernatural forces.[10] Macbeth did have a wife, but it is not clear if she was as power-hungry and ambitious as Boece portrayed her, which served his purpose of having even Macbeth realise that he lacked a proper claim to the throne, and only took it at the urging of his wife.[10] Holinshed accepted Boece's version of Macbeth's reign at face value and included it in his Chronicles.[10] Shakespeare saw the dramatic possibilities in the story as related by Holinshed and used it as the basis for the play.[10]

Only Shakespeare's version of the story involves Macbeth killing the king in Macbeth's own castle. Scholars have seen this change as adding the worst violation of hospitality. Common versions at the time involved Duncan being killed in an ambush at Inverness. Shakespeare conflated the story of Donwald and King Duff in what was a significant change to the story.[11]

Shakespeare made another important change. In the Chronicles, Banquo is an accomplice in Macbeth's murder of King Duncan and plays an important part in ensuring that Macbeth, not Malcolm, takes the throne in the coup that follows.[12] It was established in the 19th century that Banquo is not actually a historical person, but in Shakespeare's day Banquo was thought to be an ancestor of the Stuart King James I.[13] To portray the king's supposed ancestor as a murderer would have been risky. Other authors of the time who wrote about Banquo, such as Jean de Schelandre in his Stuartide, also changed history by portraying Banquo as a noble man and not a murderer, probably for the same reasons.[14] Shakespeare may have altered Banquo's character also because there was no dramatic need for another accomplice to the murder. There was, however, a need to give a dramatic contrast to Macbeth, a role which many scholars argue is filled by Banquo.[12]

Other scholars maintain that a strong argument can be made for associating Macbeth with the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.[2] As presented by Harold Bloom in 2008:

[S]cholars cite the existence of several topical references in Macbeth to the events of that year, namely the execution of the Father Henry Garnett for his alleged complicity in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, as referenced in the porter's scene.[2]

Those arrested for their role in the Gunpowder Plot refused to give direct answers to the questions posed to them by their interrogators, which reflected the influence of the Jesuit practice of equivocation.[15] By having Macbeth speak of "juggling fiends [...] that palter with us in a double sense, / That keep the word of promise to our ear, / And break it to our hope" (5.8.19-22. Mason), Shakespeare confirmed James's belief that equivocation was a "wicked" practice, which reflected in turn the "wickedness" of the Catholic Church.[15] Garnett had in his possession A Treatise on Equivocation. The Weird Sisters in the play often engage in equivocation and so do the apparitions which they conjure. For example the third such apparition tells Macbeth that he "shall never vanquished be until / Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill / Shall come against him"(4.1.91-93).[16] Macbeth interprets this utterance as meaning never, but it refers to the branches of the trees which are carried by the troops to hide their numbers.[17]

Date and text

Macbeth cannot be dated precisely, but it is usually placed near to Shakespeare's other greatest tragedies, Hamlet and Othello and King Lear.[18] Some scholars have placed the original writing of the play as early as 1599,[2] but most believe that the play is unlikely to have been composed earlier than 1603, as the play is widely seen to celebrate King James' ancestors and the Stuart accession to the throne in 1603. Many people agree that Macbeth was written in the year 1606,[19][20][21] citing multiple allusions to the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 and its ensuing trials. However, A. R. Braunmuller finds the 1605–06 arguments inconclusive, and argues only for an earliest date of 1603.[22] Simon Forman saw Macbeth at the Globe in 1610 or 1611.[23] Macbeth was first printed in the First Folio of 1623.

Accession of James

When James became king of England, a feeling of uncertainty settled over the nation. James was a Scottish king and the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, a staunch Catholic and English traitor. In the words of critic Robert Crawford,

Macbeth was a play for a post-Elizabethan England facing up to what it might mean to have a Scottish king. England seems comparatively benign, while its northern neighbour is mired in a bloody, monarch-killing past. ... Macbeth may have been set in medieval Scotland, but it was filled with material of interest to England and England's ruler.[24]

Critics argue that the content of the play is clearly a message to James, the new Scottish King of England. Likewise, the critic Andrew Hadfield has noted the contrast which the play draws between the saintly King Edward the Confessor of England, who has the power of the royal touch to cure scrofula, and whose realm is portrayed as peaceful and prosperous, against the bloody chaos of Scotland.[25] In his 1598 book, The Trew Law of Free Monarchies, James had asserted that kings are always right, if not just, and that his subjects owe him total loyalty at all times, writing that even if a king is a tyrant, his subjects must never rebel and just endure his tyranny for their own good.[26] James had argued that the tyranny was preferable to the problems caused by rebellion. By contrast, Shakespeare argued in Macbeth for the right of the subjects to overthrow a tyrant king, an implied criticism of James's theories if applied to England.[26] Hadfield has also noted a curious aspect of the play, its implication that primogeniture is the norm in Scotland, but Duncan has to nominate his son Malcolm to be his successor while Macbeth is accepted without protest by the Scottish lairds as their king despite being an usurper.[27] Hadfield has argued that this aspect of the play, the thanes apparently choosing their king, was a reference to the Stuart claim to the English throne, and the attempts of the English Parliament to block the succession of James's Catholic mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, from succeeding to the English throne.[28] Hadfield has argued that Shakespeare had implied that James was indeed the rightful king of England, but owed his throne not to divine favour, as James would have it, but rather due to the willingness of the English Parliament to accept the Protestant son of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, as their king.[28] James believed himself descended from Banquo,[29] which suggests to some people that the parade of eight kings in Act 4 is a compliment to King James.[30]

Gunpowder Plot

_by_Claes_(Nicolaes)_Jansz_Visscher.jpg.webp)

Many people agree that Macbeth was written in the year 1606,[19][20][21] citing multiple allusions to the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 and its ensuing trials. The Porter particularly "devil-porter[s] it" and fancifully welcomes an equivocator and a farmer and a tailor into Hell (2.3.1–21), and this is believed to be an allusion to the trial on 28 March 1606 and the execution on 3 May 1606 of the Jesuit Henry Garnet, who used the alias "Farmer", "equivocator" here referring to Garnet's defence of "equivocation".[31][22][lower-alpha 2] The porter says that the equivocator "committed treason enough for God's sake" (2.3.9–10), which specifically connects equivocation and treason and ties it to the Jesuit belief that equivocation was only lawful when used "for God's sake", strengthening the allusion to Garnet. He adds that the equivocator "could not equivocate to heaven" (2.3.10–11), echoing grim jokes that were current on the eve of Garnet's execution, that Garnet would be "hanged without equivocation", and that at his execution he was asked "not to equivocate with his last breath."[33] The "English tailor" which the porter mentions (2.3.13) has been seen as an allusion to Hugh Griffin, a tailor who was questioned by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 27 November and 3 December 1607 for the part he played in Garnet's "miraculous straw", an infamous head of straw that was stained with Garnet's blood which congealed and resembled Garnet's portrait and was hailed by Catholics as a miracle. The tailor Griffin became notorious and the subject of verses published with his portrait on the title page.[34] Further indication of the date is taken from Lady Macbeth's words to her husband, "Look like the innocent flower, but be the serpent under't" (1.5.74–75), which may be an allusion to a medal struck in 1605 to commemorate King James' escape, which depicted a serpent hiding among lilies and roses.[35]

Garry Wills provides further evidence that Macbeth is a Gunpowder Play. He points out that every Gunpowder Play contains

a necromancy scene, regicide attempted or completed, references to equivocation, scenes that test loyalty by use of deceptive language, and a character who sees through plots—along with a vocabulary similar to the Plot in its immediate aftermath (words like train, blow, vault) and an ironic recoil of the Plot upon the Plotters (who fall into the pit they dug).[19]

The play utilizes a few key words that the audience would have recognized as allusions to the Plot. In one sermon in 1605, Lancelot Andrewes stated, regarding the failure of the Plotters on God's day, "Be they fair or foul, glad or sad (as the poet calleth Him) the great Diespiter, 'the Father of days' hath made them both."[36] Shakespeare repeats the words "fair" and "foul" in the first words of his witches, and Macbeth echoes it in his first line.[37] In the words of Jonathan Gil Harris,

the play expresses the "horror unleashed by a supposedly loyal subject who seeks to kill a king and the treasonous role of equivocation. The play even echoes certain keywords from the scandal—the 'vault' beneath the House of Parliament in which Guy Fawkes stored thirty kegs of gunpowder and the 'blow' about which one of the conspirators had secretly warned a relative who planned to attend the House of Parliament on 5 November...Even though the Plot is never alluded to directly, its presence is everywhere in the play, like a pervasive odor."[36]

The Sisters

Scholars also cite an entertainment seen by King James at Oxford in the summer of 1605 which featured three "sibyls" like the Weird Sisters. Kermode surmises that Shakespeare could have heard about this and alluded to it.[31]

.jpg.webp)

One suggested allusion supporting a date in late 1606 is the first witch's tale of her encounter with a sailor's wife: "'Aroint thee, witch!' the rump-fed ronyon cries. / Her husband's to Aleppo gone, master o' the Tiger" (1.3.6–7). This has been thought to allude to the Tiger, a ship which returned to England 27 June 1606 after a disastrous voyage in which many of the crew were killed by pirates. The witch speaks of the sailor: "He shall live a man forbid: / Weary se'nnights nine times nine / Shall he dwindle, peak, and pine" (1.3.21–22). The historical ship was at sea 567 days, the product of 7x9x9, which has been taken as a confirmation of the allusion that, if correct, confirms that the lines were written or amended later than July 1606.[38][30]

Subsequent evidence

The play is not thought to have been written any later than 1607, since, as Kermode notes, there are "fairly clear allusions to the play in 1607."[31] One notable reference is in Francis Beaumont's Knight of the Burning Pestle, first performed in 1607.[39][40] The following lines (Act V, Scene 1, 24–30) are, according to scholars,[41][42] a clear allusion to the scene in which Banquo's ghost haunts Macbeth at the dinner table:

When thou art at thy table with thy friends,

Merry in heart, and filled with swelling wine,

I'll come in midst of all thy pride and mirth,

Invisible to all men but thyself,

And whisper such a sad tale in thine ear

Shall make thee let the cup fall from thy hand,

And stand as mute and pale as death itself.[43]

Simon Forman saw Macbeth at the Globe in 1610 or 1611.[23]

Text

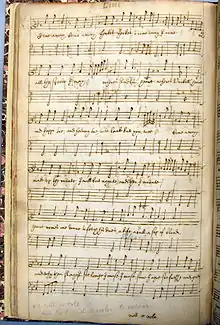

Macbeth was first printed in the First Folio of 1623, and the Folio is the only source for the text. Some scholars contend that the Folio text was abridged and rearranged from an earlier manuscript or prompt book.[44] Stage cues for two songs are often cited as interpolations. The lyrics are not included in the Folio, but are included in Thomas Middleton's play The Witch, which was written between the accepted date for Macbeth (1606) and the printing of the Folio.[45] Many scholars believe that these songs were editorially inserted into the Folio, though whether they were Middleton's songs or preexisting songs is not certain.[46] It is also widely believed that the character of Hecate, as well as some lines of the First Witch in multiple scenes (3.5) (4.1 124–131), were not part of Shakespeare's original play, added by the Folio editors and possibly written by Middleton.[47] But "there is no completely objective proof" of such interpolation.[48]

Pronunciations

The 'reconstructive movement' was concerned with the recreation of Elizabethan acting conditions, and would eventually lead to the creation of Shakespeare's Globe and similar replicas. One of the movement's offshoots was the reconstruction of Elizabethan pronunciation. For example Bernard Miles' 1951 Macbeth, for which linguists from University College London were employed to create a transcript of the play in Elizabethan English, then an audio recording of that transcription from which the actors learned their lines.[49]

The pronunciation of many words evolves over time. In Shakespeare's day, for example, "heath" was pronounced as "heth" ("or a slightly elongated 'e' as in the modern 'get'"),[50] so that it rhymed with "Macbeth":[51]

Second Witch: Upon the heath.

Third Witch: There to meet with Macbeth. (1.1.6-7)

A scholar of antique pronunciation writes, "Heath would have made a close (if not exact) rhyme with the "-eth" of Macbeth, which was pronounced with a short 'i' as in 'it'."[50]

In the theatre programme notes, "much was made of how OP (Original Pronunciation) performance reintroduces lost rhymes such as the final couplet: 'So thanks to all at once, and to each one, / Whom we invite to see us crowned at Scone'" (5.11.40–41). Here, 'one' sounds like 'own'. The Witches benefited most in this regard. 'Babe' sounded like 'bab' and rhymed with 'drab':[51]

Finger of birth-strangled babe

Ditch-delivered by a drab,

Make the gruel thick and slab. (4.1.30-32)

Eoin Price wrote, "I found the OP rendition of Banquo's brilliant question 'Or have we eaten on the insane root / That takes the raison prisoner?' unduly amusing". He adds,

:... 'fear' had two pronunciations: the standard modern pronunciation being one, and 'fair' being the other. Mostly, the actors seemed to pronounce it in a way which accords with the modern standard, but during one speech, Macbeth said 'fair'. This seems especially significant in a play determined to complicate the relationship between 'fair' and 'foul'. I wonder, then, if the punning could be extended throughout the production. Would Banquo's lines, 'Good sir, why do you start and seem to fear / Things that do sound so fair?' (1.3.49–50) be fascinatingly illuminated, or merely muddled, by this punning? Perhaps this is a possibility the cast already experimented with and chose to discard, but, for sure, an awareness of the possibility of a 'fair/fear' pun can have interesting ramifications for the play.[51]

Themes and motifs

Macbeth is an anomaly among Shakespeare's tragedies in certain critical ways. It is short: more than a thousand lines shorter than Othello and King Lear, and only slightly over half the length of Hamlet. This brevity has suggested to many critics that the received version is based on a heavily cut source, perhaps a prompt-book for a particular performance. This would reflect other Shakespeare plays existing in both Quarto and the Folio, where the Quarto versions are usually longer than the Folio versions. Macbeth was first printed in the First Folio and has no Quarto version – if there was a Quarto version, it would probably be longer than the Folio version.[52] The brevity has also been connected to other unusual features: the fast pace of the first act has seemed to be "stripped for action", and the comparative flatness of characters other than Macbeth is unusual,[53] and the strangeness of Macbeth himself when compared with other of Shakespeare's tragic heroes is odd. A. C. Bradley, in considering this question, concluded that the play "always was an extremely short one", noting that the witch scenes and battle scenes would have taken up some time in performance. He remarked: "I do not think that, in reading, we feel Macbeth to be short: certainly we are astonished when we hear it is about half as long as Hamlet. Perhaps in the Shakespearean theatre too it seemed to occupy a longer time than the clock recorded."[52]

As a tragedy of character

.jpg.webp)

At least since the days of Alexander Pope and Samuel Johnson, analysis of the play has centred on the question of Macbeth's ambition, commonly seen as so dominant a trait that it defines the character. Johnson asserted that Macbeth, though esteemed for his military bravery, is wholly reviled.

This opinion recurs in critical literature. According to Caroline Spurgeon it is also supported by Shakespeare himself, who apparently intended to degrade his hero by vesting Macbeth with clothes unsuited to him and to make him look ridiculous by several nimisms he applies: His garments seem either too big or too small for him – as his ambition is too big and his character too small for his new and unrightful role as king. When he feels as if "dressed in borrowed robes", after his new title as Thane of Cawdor, prophesied by the witches, has been confirmed by Ross (I, 3, ll. 108–109), Banquo comments:

"New honours come upon him,

Like our strange garments, cleave not to their mould,

But with the aid of use" (I, 3, ll. 145–146).

And, at the end, when Macbeth is at bay at Dunsinane, Caithness sees him as a man trying in vain to fasten a large garment on him with too small a belt:

"He cannot buckle his distemper'd cause

Within the belt of rule" (V, 2, ll. 14–15)

Angus, in a similar nimism, sums up what everybody has thought since Macbeth's accession to power:

"now does he feel his title

Hang loose about him, like a giant's robe

upon a dwarfish thief" (V, 2, ll. 18–20).[54]

Like Shakespeare's Richard III of England, but without that character's perversely appealing exuberance, Macbeth wades through blood until his inevitable fall. As Kenneth Muir writes, "Macbeth has not a predisposition to murder; he has merely an inordinate ambition that makes murder itself seem to be a lesser evil than failure to achieve the crown."[55]

Yet for other critics it has not been so easy to resolve the question of Macbeth's motivation. Robert Bridges, for example, perceived a paradox: a character able to express such convincing horror before Duncan's murder would likely be incapable of committing the crime.[56] For many critics, Macbeth's motivations in the first act appear vague and insufficient. John Dover Wilson hypothesised that Shakespeare's original text had an extra scene or scenes where husband and wife discussed their plans. This interpretation is not fully provable. However, the motivating role of ambition for Macbeth is universally recognised. The evil actions motivated by his ambition seem to trap him in a cycle of increasing evil, as Macbeth himself recognises:

"I am in blood

Stepp'd in so far that, should I wade no more,

Returning were as tedious as go o'er" (III, 4, ll. 134-36).

While working on Russian translations of Shakespeare's works, Boris Pasternak compared Macbeth to Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Pasternak argues that "neither Macbeth or Raskolnikov is a born criminal or a villain by nature. They are turned into criminals by faulty rationalizations, by deductions from false premises." He goes on to argue that Lady Macbeth is "feminine ... one of those active, insistent wives" who becomes her husband's "executive, more resolute and consistent than he is himself." According to Pasternak, she is only helping Macbeth carry out his own wishes, to her own detriment.[57]

As a tragedy of moral order

.jpg.webp)

The disastrous consequences of Macbeth's ambition are not limited to him. Almost from the moment of the murder, the play depicts Scotland as a land shaken by inversions of the natural order. Shakespeare may have intended a reference to the great chain of being, although the play's images of disorder are mostly not specific enough to support detailed intellectual readings.[58] He may also have intended an elaborate compliment to James's belief in the divine right of kings, although this hypothesis, outlined at greatest length by Henry N. Paul, is not universally accepted. As in Julius Caesar, though, perturbations in the political sphere are echoed and even amplified by events in the material world. Among the most often depicted of the inversions of the natural order is sleep. Macbeth says: "Methought I heard a voice cry, 'Sleep no more. / Macbeth does murder sleep'" (2.2.36-37), and this is figuratively mirrored in Lady Macbeth's sleepwalking.

Macbeth's generally accepted indebtedness to medieval tragedy is often seen as significant in the play's treatment of moral order. Glynne Wickham connects the play, through the Porter, to a mystery play on the harrowing of hell. Howard Felperin argues that the play has a more complex attitude toward "orthodox Christian tragedy" than is often admitted. He sees a kinship between the play and the tyrant plays within the medieval liturgical drama.

_Tate.jpg.webp)

The theme of androgyny is often seen as a special aspect of the theme of disorder. Inversion of normative gender roles is most famously associated with the witches and with Lady Macbeth as she appears in the first act. Whatever Shakespeare's degree of sympathy with such inversions, the play ends with a thorough return to normative gender values. Some feminist psychoanalytic critics, such as Janet Adelman, have connected the play's treatment of gender roles to its larger theme of inverted natural order. In this light, Macbeth is punished for his violation of the moral order by being removed from the cycles of nature (which are figured as female). Nature itself (as embodied in the movement of Birnam Wood) is part of the restoration of moral order.

As a poetic tragedy

Critics in the early twentieth century reacted against what they saw as an excessive dependence on the study of character in criticism of the play. This dependence, though most closely associated with Andrew Cecil Bradley, is clear as early as the time of Mary Cowden Clarke, who offered precise, if fanciful, accounts of the predramatic lives of Shakespeare's female leads. For example she suggested that the child which Lady Macbeth refers to in the first act died during a foolish military action.

Witchcraft and evil

In the play, the Three Witches represent darkness and chaos and conflict, while their role is as agents and witnesses.[59] Their presence communicates treason and impending doom. During Shakespeare's day, witches were seen as worse than rebels, "the most notorious traytor and rebell that can be."[60] They were not only political traitors, but spiritual traitors as well. Much of the confusion that springs from them comes from their ability to straddle the play's borders between reality and the supernatural: They are so deeply entrenched in both worlds that it is unclear whether they control fate or whether they are merely its agents. They defy logic, not being subject to the rules of the real world.[61]

The witches' lines in the first act, "Fair is foul, and foul is fair: Hover through the fog and filthy air" (1.1.9–10), are often said to set the tone for the rest of the play, by establishing a sense of confusion. Indeed, the play is filled with situations where evil is depicted as good, while good is rendered evil. The line "Double, double, toil and trouble" (4.1.10 ff) communicates the witches' intent clearly: They seek only trouble for the mortals around them.[62] The witches' spells are remarkably similar to the spells of the witch Medusa in Anthony Munday's play Fidele and Fortunio published in 1584, and Shakespeare may have been influenced by these.

The witches do not tell Macbeth directly to kill King Duncan; they use a subtle form of temptation when they tell Macbeth that he will be king. By placing the thought in his mind, they effectively guide him on the path to his own destruction. This follows the pattern of temptation used at the time of Shakespeare. First, they argued, a thought is put in a man's mind, then the person may either indulge in the thought or reject it. Macbeth indulges in it, while Banquo rejects.[62]

According to J.A. Bryant Jr., Macbeth also makes use of Biblical parallels, notably between King Duncan's murder and the murder of Christ:

No matter how one looks at it, whether as history or as tragedy, Macbeth is distinctively Christian. One may simply count the Biblical allusions as Richmond Noble has done; one may go further and study the parallels between Shakespeare's story and the Old Testament stories of Saul and Jezebel as Miss Jane H. Jack has done; or one may examine with W.C. Curry the progressive degeneration of Macbeth from the point of view of medieval theology.[63]

Language

And pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubin, horsed

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth, 1.7.21–25

Superstition and "The Scottish Play"

Actors and others in the theatre industry have considered it bad luck to mention Macbeth by name while inside a theatre, sometimes referring to it indirectly, as "The Scottish Play"[64] or "MacBee", or when referring to the character and not the play, "Mr. and Mrs. M", or "The Scottish King".

This is because Shakespeare (or the play's revisers) are said to have used the spells of real witches in his text, purportedly angering the witches and causing them to curse the play.[65] Thus, to say the name of the play inside a theatre is believed to doom the production to failure, and perhaps cause physical injury or death to cast members. There are stories of accidents and misfortunes and even deaths taking place during runs of Macbeth.[64]

According to the actor Sir Donald Sinden, in his Sky Arts TV series Great West End Theatres,

contrary to popular myth, Shakespeare's tragedy Macbeth is not the unluckiest play as superstition likes to portray it. Exactly the opposite! The origin of the unfortunate moniker dates back to repertory theatre days when each town and village had at least one theatre to entertain the public. If a play was not doing well, it would invariably get 'pulled' and replaced with a sure-fire audience pleaser – Macbeth guaranteed full-houses. So when the weekly theatre newspaper, The Stage was published, listing what was on in each theatre in the country, it was instantly noticed what shows had not worked the previous week, as they had been replaced by a definite crowd-pleaser. More actors have died during performances of Hamlet than in the "Scottish play" as the profession still calls it. It is forbidden to quote from it backstage as this could cause the current play to collapse and have to be replaced, causing possible unemployment.[66]

Several methods exist to dispel the curse, depending on the actor. One, attributed to Michael York, is to immediately leave the building which the stage is in with the person who uttered the name, walk around it three times, spit over their left shoulders, say an obscenity then wait to be invited back into the building.[67] A related practice is to spin around three times as fast as possible on the spot, sometimes accompanied by spitting over their shoulder, and uttering an obscenity. Another popular "ritual" is to leave the room, knock three times, be invited in, and then quote a line from Hamlet. Yet another is to recite lines from The Merchant of Venice, thought to be a lucky play.[68]

Performance history

Shakespeare's day to the Interregnum

The only eyewitness account of Macbeth from within Shakespeare's lifetime was written by Simon Forman. He saw a performance at the Globe on 20 April 1610 or 1611.[69][23] Scholars have noted discrepancies between Forman's account and the Folio text. For example Forman was an astrologer and interested in witchcraft, but he does not mention Hecate nor the scene with the cauldron and apparitions, and he calls the witches "3 women feiries or Nimphes".[70] He does not mention Birnam Wood nor a man not born of woman.[69][5] His account is not considered reliable evidence of what he actually saw.[45] The notes which he made about plays are considered "idiosyncratic", and they lack accuracy and completeness.[71] His interest did not seem to be in "giving full accounts of the productions".[71]

The Folio text is thought by some to be an alteration of the original play. This has led to speculation that the play as we know it was an adaptation for indoor performance at the Blackfriars Theatre (which was operated by the King's Men from 1608), and speculation that it represents a specific performance before King James.[72][73][74] The play contains more musical cues than any other play in the canon as well as a significant use of sound effects.[75]

Restoration and eighteenth century

—Sheridan Knowles on Sarah Siddons' sleepwalking scene[76]

The Puritan government closed all theatres on 6 September 1642. On the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, two patent companies were established, the King's Company and the Duke's Company, and the existing theatrical repertoire was divided between them.[77] The founder of the Duke's Company, Sir William Davenant, adapted Macbeth. His version dominated for about eighty years. His changes included expansion of Lady Macduff to be a foil for Lady Macbeth, and provision of new songs and dances and 'flying' for the witches.[78] There were, however, performances which evaded the monopoly of the Duke's Company, such as a puppet version.[79]

Macbeth was a favourite of the seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys. He saw the play:

- 5 November 1664 ("admirably acted")

- 28 December 1666 ("most excellently acted")

- 7 January 1667 ("though I saw it lately, yet [it] appears a most excellent play in all respects")

- 19 April 1667 ("one of the best plays for a stage ... that ever I saw")

- 16 October 1667 ("was vexed to see Young, who is but a bad actor at best, act Macbeth in the room of Betterton, who, poor man! is sick")

- 6 November 1667 ("[at] Macbeth, which we still like mightily")

- 12 August 1668 ("saw Macbeth, to our great content")

- 21 December 1668, on which date the king and court were also present in the audience.[80]

The first professional performances of Macbeth in North America were probably those of The Hallam Company.[81]

David Garrick revived the play in 1744, abandoning Davenant's version and advertising it "as written by Shakespeare". But he retained much of Davenant's popular additions for the witches, and wrote a death speech for Macbeth. He also cut Shakespeare's drunken porter and the murder of Lady Macduff's son and Malcolm's testing of Macduff.[82] Garrick's greatest stage partner was Hannah Pritchard. She premiered as his Lady Macbeth in 1747. Garrick dropped the play from his repertoire when Pritchard retired from the stage.[83] Pritchard was the first actress to receive acclaim in the role of Lady Macbeth, partly due to the removal of Davenant's material.[84] Garrick's portrayal focused on the inner life of Macbeth, endowing him with an innocence vacillating between good and evil, and betrayed by outside influences. He portrayed a man capable of observing himself, as if a part of him remained untouched by what he had done, the play moulding him into a man of sensibility, rather than him descending into a tyrant.[85]

John Philip Kemble first played Macbeth in 1778.[86] Though usually regarded as the antithesis of Garrick, Kemble refined aspects of Garrick's portrayal.[87] Kemble's sister, Sarah Siddons, became a "towering and majestic" legend in the role of Lady Macbeth.[88][89] Siddons' Lady Macbeth, in contrast to Hannah Pritchard's savage and demonic portrayal, was thought terrifying yet tenderly human.[90] In portraying her actions as motivated by love for her husband, Siddons deflected some of the moral responsibility from him.[86] Audiences seem to have found the sleepwalking scene particularly mesmerising: Hazlitt said of it that "all her gestures were involuntary and mechanical ... She glided on and off the stage almost like an apparition."[91]

Kemble dispensed with Banquo's ghost in 1794. The play was so well known that he expected his audience to fully know about the ghost, and his change allowed them to see Macbeth's reaction as his wife and guests see it.[92]

Ferdinand Fleck, notable as the first German actor to present Shakespeare's tragic roles in their fullness, played Macbeth at the Berlin National Theatre from 1787. Unlike his English counterparts, he portrayed Macbeth as achieving his stature after the murder of Duncan, growing in presence and confidence, thereby enabling stark contrasts, such as in the banquet scene, which he ended babbling like a child.[93]

Nineteenth century

Performances outside the patent theatres were instrumental in bringing the monopoly to an end. Robert Elliston, for example, produced a popular adaptation of Macbeth in 1809 at the Royal Circus described in its publicity as "this matchless piece of pantomimic and choral performance", which circumvented the illegality of speaking Shakespeare's words through mimed action, singing, and doggerel verse written by J. C. Cross.[95][96]

In 1809, in an unsuccessful attempt to take Covent Garden upmarket, Kemble installed private boxes, increasing admission prices to pay for the improvements. The inaugural run at the newly renovated theatre was Macbeth, which was disrupted for over two months with cries of "Old prices!" and "No private boxes!" until Kemble capitulated to the protestors' demands.[97]

Edmund Kean at Drury Lane gave a psychological portrayal of the central character, with a common touch, but was ultimately unsuccessful in the role. However he did pave the way for the most acclaimed performance of the nineteenth century, that of William Charles Macready. Macready played the role over a 30-year period, firstly at Covent Garden in 1820 and finally in his retirement performance. Although his playing evolved over the years, it was noted throughout for the tension between the idealistic aspects and the weaker, venal aspects of Macbeth's character. His staging was full of spectacle, including several elaborate royal processions.[98]

In 1843 the Theatres Regulation Act finally brought the patent companies' monopoly to an end.[99] From that time until the end of the Victorian era, London theatre was dominated by the actor-managers, and the style of presentation was "pictorial" – proscenium stages filled with spectacular stage-pictures, often featuring complex scenery, large casts in elaborate costumes, and frequent use of tableaux vivant.[100][101] Charles Kean (son of Edmund), at London's Princess's Theatre from 1850 to 1859, took an antiquarian view of Shakespeare performance, setting his Macbeth in a historically accurate eleventh-century Scotland.[102] His leading lady, Ellen Tree, created a sense of the character's inner life: The Times' critic saying "The countenance which she assumed ... when luring on Macbeth in his course of crime, was actually appalling in intensity, as if it denoted a hunger after guilt."[103] At the same time, special effects were becoming popular: for example in Samuel Phelps' Macbeth the witches performed behind green gauze, enabling them to appear and disappear using stage lighting.[104]

In 1849, rival performances of the play sparked the Astor Place riot in Manhattan. The popular American actor Edwin Forrest, whose Macbeth was said to be like "the ferocious chief of a barbarous tribe"[105] played the central role at the Broadway Theatre to popular acclaim, while the "cerebral and patrician"[97] English actor Macready, playing the same role at the Astor Place Opera House, suffered constant heckling. The existing enmity between the two men (Forrest had openly hissed Macready at a recent performance of Hamlet in Britain) was taken up by Forrest's supporters – formed from the working class and lower middle class and anti-British agitators, keen to attack the upper-class pro-British patrons of the Opera House and the colonially-minded Macready. Nevertheless, Macready performed the role again three days later to a packed house while an angry mob gathered outside. The militia tasked with controlling the situation fired into the mob. In total, 31 rioters were killed and over 100 injured.[97][106][107][108]

Charlotte Cushman is unique among nineteenth century interpreters of Shakespeare in achieving stardom in roles of both genders. Her New York debut was as Lady Macbeth in 1836, and she would later be admired in London in the same role in the mid-1840s.[109][110] Helen Faucit was considered the embodiment of early-Victorian notions of femininity. But for this reason she largely failed when she eventually played Lady Macbeth in 1864: her serious attempt to embody the coarser aspects of Lady Macbeth's character jarred harshly with her public image.[111] Adelaide Ristori, the great Italian actress, brought her Lady Macbeth to London in 1863 in Italian, and again in 1873 in an English translation cut in such a way as to be, in effect, Lady Macbeth's tragedy.[112]

Henry Irving was the most successful of the late-Victorian actor-managers, but his Macbeth failed to curry favour with audiences. His desire for psychological credibility reduced certain aspects of the role: He described Macbeth as a brave soldier but a moral coward, and played him untroubled by conscience – clearly already contemplating the murder of Duncan before his encounter with the witches.[113][lower-alpha 3] Irving's leading lady was Ellen Terry, but her Lady Macbeth was unsuccessful with the public, for whom a century of performances influenced by Sarah Siddons had created expectations at odds with Terry's conception of the role.[115][116]

Late nineteenth-century European Macbeths aimed for heroic stature, but at the expense of subtlety: Tommaso Salvini in Italy and Adalbert Matkowsky in Germany were said to inspire awe, but elicited little pity.[116]

20th century to present

Two developments changed the nature of Macbeth performance in the 20th century: first, developments in the craft of acting itself, especially the ideas of Stanislavski and Brecht; and second, the rise of the dictator as a political icon. The latter has not always assisted the performance: it is difficult to sympathise with a Macbeth based on Hitler, Stalin, or Idi Amin.[118]

Barry Jackson, at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1923, was the first of the 20th-century directors to costume Macbeth in modern dress.[119]

In 1936, a decade before his film adaptation of the play, Orson Welles directed Macbeth for the Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, using black actors and setting the action in Haiti: with drums and Voodoo rituals to establish the Witches scenes. The production, dubbed The Voodoo Macbeth, proved inflammatory in the aftermath of the Harlem riots, accused of making fun of black culture and as "a campaign to burlesque negroes" until Welles persuaded crowds that his use of black actors and voodoo made important cultural statements.[120][121]

A performance which is frequently referenced as an example of the play's curse was the outdoor production directed by Burgess Meredith in 1953 in the British colony of Bermuda, starring Charlton Heston. Using the imposing spectacle of Fort St. Catherine as a key element of the set, the production was plagued by a host of mishaps, including Charlton Heston being burned when his tights caught fire.[122][123]

The critical consensus is that there have been three great Macbeths on the English-speaking stage in the 20th century, all of them commencing at Stratford-upon-Avon: Laurence Olivier in 1955, Ian McKellen in 1976 and Antony Sher in 1999.[124] Olivier's portrayal (directed by Glen Byam Shaw, with Vivien Leigh as Lady Macbeth) was immediately hailed as a masterpiece. Kenneth Tynan expressed the view that it succeeded because Olivier built the role to a climax at the end of the play, whereas most actors spend all they have in the first two acts.[118][125]

The play caused grave difficulties for the Royal Shakespeare Company, especially at the (then) Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. Peter Hall's 1967 production was (in Michael Billington's words) "an acknowledged disaster" with the use of real leaves from Birnham Wood getting unsolicited first-night laughs, and Trevor Nunn's 1974 production was (Billington again) "an over-elaborate religious spectacle".[126]

But Nunn achieved success for the RSC in his 1976 production at the intimate Other Place, with Ian McKellen and Judi Dench in the central roles.[127] A small cast worked within a simple circle, and McKellen's Macbeth had nothing noble or likeable about him, being a manipulator in a world of manipulative characters. They were a young couple, physically passionate, "not monsters but recognisable human beings",[lower-alpha 4] but their relationship atrophied as the action progressed.[129][128]

The RSC again achieved critical success in Gregory Doran's 1999 production at The Swan, with Antony Sher and Harriet Walter in the central roles, once again demonstrating the suitability of the play for smaller venues.[130][131] Doran's witches spoke their lines to a theatre in absolute darkness, and the opening visual image was the entrance of Macbeth and Banquo in the berets and fatigues of modern warfare, carried on the shoulders of triumphant troops.[131] In contrast to Nunn, Doran presented a world in which king Duncan and his soldiers were ultimately benign and honest, heightening the deviance of Macbeth (who seems genuinely surprised by the witches' prophesies) and Lady Macbeth in plotting to kill the king. The play said little about politics, instead powerfully presenting its central characters' psychological collapse.[132]

Macbeth returned to the RSC in 2018, when Christopher Eccleston played the title role, with Niamh Cusack as his wife, Lady Macbeth.[133] The play later transferred to the Barbican in London.

In Soviet-controlled Prague in 1977, faced with the illegality of working in theatres, Pavel Kohout adapted Macbeth into a 75-minute abridgement for five actors, suitable for "bringing a show in a suitcase to people's homes".[134][lower-alpha 5]

Spectacle was unfashionable in Western theatre throughout the 20th century. In East Asia, however, spectacular productions have achieved great success, including Yukio Ninagawa's 1980 production with Masane Tsukayama as Macbeth, set in the 16th century Japanese Civil War.[135] The same director's tour of London in 1987 was widely praised by critics, even though (like most of their audience) they were unable to understand the significance of Macbeth's gestures, the huge Buddhist altar dominating the set, or the petals falling from the cherry trees.[136]

Xu Xiaozhong's 1980 Central Academy of Drama production in Beijing made every effort to be unpolitical (necessary in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution): yet audiences still perceived correspondences between the central character (whom the director had actually modelled on Louis Napoleon) and Mao Zedong.[137] Shakespeare has often been adapted to indigenous theatre traditions, for example the Kunju Macbeth of Huang Zuolin performed at the inaugural Chinese Shakespeare Festival of 1986.[138] Similarly, B. V. Karanth's Barnam Vana of 1979 had adapted Macbeth to the Yakshagana tradition of Karnataka, India.[139] In 1997, Lokendra Arambam created Stage of Blood, merging a range of martial arts, dance and gymnastic styles from Manipur, performed in Imphal and in England. The stage was literally a raft on a lake.[140]

Throne of Blood (蜘蛛巣城 Kumonosu-jō, Spider Web Castle) is a 1957 Japanese samurai film co-written and directed by Akira Kurosawa. The film transposes Macbeth from Medieval Scotland to feudal Japan, with stylistic elements drawn from Noh drama. Kurosawa was a fan of the play and planned his own adaptation for several years, postponing it after learning of Orson Welles' Macbeth (1948). The film won two Mainichi Film Awards.

The play has been translated and performed in various languages in different parts of the world, and Media Artists was the first to stage its Punjabi adaptation in India. The adaptation by Balram and the play directed by Samuel John have been universally acknowledged as a milestone in Punjabi theatre.[141] The unique attempt involved trained theatre experts and the actors taken from a rural background in Punjab. Punjabi folk music imbued the play with the native ethos as the Scottish setting of Shakespeare's play was transposed into a Punjabi milieu.[142]

In September, 2018, Macbeth was faithfully adapted into a fully illustrated Manga edition, by Manga Classics, an imprint of UDON Entertainment.[143]

Notes and references

Notes

- For the first performance in 1607, see Gurr 2009, p. 293, Thomson 1992, p. 64, and Wickham 1969, p. 231. For the date of composition, see Brooke 2008, p. 1 and Clark & Mason 2015, p. 13

- For details on Garnet, see Perez Zagorin's article, "The Historical Significance of Lying and Dissimulation" (1996), in Social Research.[32]

- Similar criticisms were made of Friedrich Mitterwurzer in Germany, whose performances of Macbeth had many unintentional parallels with Irving's.[114]

- Michael Billington, cited by Gay.[128]

- See also Tom Stoppard's Dogg's Hamlet, Cahoot's Macbeth.

References

All references to Macbeth, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Arden Shakespeare, second series edition edited by Kenneth Muir.[144] Under their referencing system, III.I.55 means act 3, scene 1, line 55. All references to other Shakespeare plays are to The Oxford Shakespeare Complete Works of Shakespeare edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor.[145]

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 1.

- Bloom 2008, p. 41.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 97.

- Muir 1984, p. xxxvi.

- Orgel 2002, p. 33.

- King of England, James I (2016). The annotated Daemonologie : a critical edition. Warren, Brett. R. ISBN 978-1-5329-6891-4. OCLC 1008940058.

- Warren 2016, p. 107.

- Coursen 1997, pp. 11–13.

- Coursen 1997, pp. 15–21.

- Thrasher 2002, p. 37.

- Coursen 1997, p. 17.

- Nagarajan 1956.

- Palmer 1886.

- Maskell 1971.

- Thrasher 2002, p. 42.

- Thrasher 2002, pp. 38–39.

- Thrasher 2002, p. 38.

- Wells & Taylor 2005, pp. 909, 1153.

- Wills 1996, p. 7.

- Muir 1985, p. 48.

- Taylor & Jowett 1993, p. 85.

- Braunmuller 1997, pp. 5–8.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 337.

- Crawford 2010.

- Hadfield 2004, pp. 84–85.

- Hadfield 2004, p. 84.

- Hadfield 2004, p. 85.

- Hadfield 2004, p. 86.

- Braunmuller 1997, pp. 2–3.

- Brooke 2008, pp. 59–64.

- Kermode 1974, p. 1308.

- Zagorin 1996.

- Rogers 1965, pp. 44–45.

- Rogers 1965, pp. 45–47.

- Paul 1950, p. 227.

- Harris 2007, pp. 473–474.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 50.

- Loomis 1956.

- Whitted 2012.

- Smith 2012.

- Dyce 1843, p. 216.

- Sprague 1889, p. 12.

- Hattaway 1969, p. 100.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 321.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 325.

- Clark & Mason 2015, pp. 326–329.

- Brooke 2008, p. 57.

- Clark & Mason 2015, pp. 329–335.

- O'Connor 2002, pp. 83, 92–93.

- Papadinis 2012, p. 31.

- Price 2014.

- Bradley, A. C., Shakespearean Tragedy

- Stoll 1943, p. 26.

- Spurgeon 1935, pp. 324–327.

- Muir 1984, p. xlviii.

- Muir 1984, p. xlvi.

- Pasternak 1959, pp. 150–152.

- "Is Macbeth Responsible For His Own Destruction English Literature Essay". UKEssays.com. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Kliman & Santos 2005, p. 14.

- Perkins 1610, p. 53.

- Coddon 1989, p. 491.

- Frye 1987.

- Bryant 1961, p. 153.

- Faires 2000.

- Tritsch 1984.

- Great West End Theatres Sky Arts. 10 August 2013

- Straczynski 2006.

- Garber 2008, p. 77.

- Brooke 2008, p. 36.

- Clark & Mason 2015, pp. 324–325.

- Clark & Mason 2015, p. 324.

- Brooke 2008, pp. 34–36.

- Orgel 2002, pp. 158–161.

- Taylor 2002, p. 2.

- Brooke 2008, pp. 35–36.

- Williams 2002, p. 119.

- Marsden 2002, p. 21.

- Tatspaugh 2003, pp. 526–527.

- Lanier 2002, pp. 28–29.

- Orgel 2002, p. 155.

- Morrison 2002, pp. 231–232.

- Orgel 2002, p. 246.

- Potter 2001, p. 188.

- Gay 2002, p. 158.

- Williams 2002, p. 124.

- Williams 2002, p. 125.

- Williams 2002, pp. 124–125.

- Potter 2001, p. 189.

- Williams 2002, pp. 125–126.

- Moody 2002, p. 43.

- Gay 2002, p. 159.

- McLuskie 2005, pp. 256–257.

- Williams 2002, p. 126.

- Gay 2002, p. 167.

- Holland 2007, pp. 38–39.

- Moody 2002, pp. 38–39.

- Lanier 2002, p. 37.

- Williams 2002, pp. 126–127.

- Moody 2002, p. 38.

- Schoch 2002, pp. 58–59.

- Williams 2002, p. 128.

- Schoch 2002, pp. 61–62.

- Gay 2002, pp. 163–164.

- Schoch 2002, p. 64.

- Morrison 2002, p. 237.

- Booth 2001, pp. 311–312.

- Holland 2002, p. 202.

- Morrison 2002, p. 238.

- Morrison 2002, p. 239.

- Gay 2002, p. 162.

- Gay 2002, pp. 161–162.

- Gay 2002, p. 164.

- Williams 2002, p. 129.

- Williams 2002, pp. 129–130.

- Gay 2002, pp. 166–167.

- Williams 2002, p. 130.

- McLuskie 2005, p. 253.

- Williams 2002, pp. 130–131.

- Smallwood 2002, p. 102.

- Forsyth 2007, p. 284.

- Hawkes 2003, p. 577.

- Hardy 2014.

- Bernews 2013.

- Williams 2002, p. 131.

- Brooke 2008, pp. 47–48.

- Billington 2003, p. 599.

- Billington 2003, pp. 599–600.

- Gay 2002, p. 169.

- Williams 2002, pp. 132–134.

- Walter 2002, p. 1.

- Billington 2003, p. 600.

- Williams 2002, p. 134.

- "Macbeth". RSC. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Holland 2007, p. 40.

- Williams 2002, pp. 134–135.

- Holland 2002, p. 207.

- Gillies et al. 2002, p. 268.

- Gillies et al. 2002, p. 270.

- Gillies et al. 2002, pp. 276–278.

- Gillies et al. 2002, pp. 278–279.

- The Tribune 2006.

- Tandon 2004.

- Manga Classics: Macbeth (2018) UDON Entertainment ISBN 978-1-947808-08-9

- Muir 1984.

- Wells & Taylor 2005.

Sources

Editions of Macbeth

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2008). Macbeth. Bloom's Shakespeare Through the Ages. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-7910-9842-4.

- Braunmuller, Albert R., ed. (1997). Macbeth. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29455-3.

- Brooke, Nicholas, ed. (2008). Macbeth. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953583-5.

- Clark, Sandra; Mason, Pamela, eds. (2015). Macbeth. The Arden Shakespeare, third series. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904271-40-6.

- Kermode, Frank, ed. (1974). Macbeth. The Riverside Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-04402-2.

- Muir, Kenneth, ed. (1984) [1951]. Macbeth (11th ed.). The Arden Shakespeare, second series. ISBN 978-1-903436-48-6.

- Papadinis, Demitra, ed. (2012). The Tragedie of Macbeth: A Frankly Annotated First Folio Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6479-1.

- Sprague, Homer B., ed. (1889). Shakespeare's Tragedy of Macbeth. New York: Silver, Burdett, & Co. hdl:2027/hvd.hn3mu1.

Secondary sources

- "'Scottish Curse' Struck Heston in Bermuda". Bernews. 7 April 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Brown, John Russell, ed. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Theatre. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285442-1.

- Booth, Michael R. (2001). "Nineteenth-Century Theatre". In Brown, John Russell (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Theatre. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 299–340. ISBN 978-0-19-285442-1.

- Bryant Jr., J. A. (1961). Hippolyta's View: Some Christian Aspects of Shakespeare's Plays. University of Kentucky Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015001989410. OL 5820486M.

- Coddon, Karin S. (1989). "'Unreal Mockery': Unreason and the Problem of Spectacle in Macbeth". ELH. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 56 (3): 485–501. doi:10.2307/2873194. eISSN 1080-6547. ISSN 0013-8304. JSTOR 2873194.

- Coursen, Herbert R. (1997). Macbeth: A Guide to the Play. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30047-X.

- Crawford, Robert (13 March 2010). "Macbeth, A True Story by Fiona Watson: The whole truth about Macbeth is not enough for Robert Crawford". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Dyce, Alexander, ed. (1843). The Works of Beaumont and Fletcher. 1. London: Edward Moxen. hdl:2027/osu.32435063510085. OL 7056519M.

- Faires, Robert (13 October 2000). "The curse of the play". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Frye, Roland Mushat (1987). "Launching the Tragedy of Macbeth: Temptation, Deliberation, and Consent in Act I". Huntington Library Quarterly. University of Pennsylvania Press. 50 (3): 249–261. doi:10.2307/3817399. eISSN 1544-399X. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817399.

- Garber, Marjorie B. (2008). Profiling Shakespeare. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96446-3.

- de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley, eds. (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Potter, Lois (2001). "Shakespeare in the theatre, 1660–1900". In de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–198. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941.012. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Gurr, Andrew (2009). The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642 (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511819520. ISBN 978-0-511-81952-0 – via Cambridge Core.

- Hadfield, Andrew (2004). Shakespeare and Renaissance Politics. Arden Critical Companions. ISBN 1-903436-17-6.

- Hardy, Jessie Moniz (16 October 2014). "In Bermuda, Shakespeare in all his glory". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Harris, Jonathan Gil (2007). "The Smell of Macbeth". Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 58 (4): 465–486. doi:10.1353/shq.2007.0062. eISSN 1538–3555 Check

|eissn=value (help). ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 4625011. S2CID 9376451. - Beaumont, Francis (1969). Hattaway, Michael (ed.). The Knight of the Burning Pestle. The New Mermaids. London: Ernest Benn. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005314193.

- Hodgdon, Barbara; Worthen, W. B., eds. (2005). A Companion to Shakespeare and Performance. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-8821-0.

- McLuskie, Kathleen (2005). "Shakespeare Goes Slumming: Harlem '37 and Birmingham '97". In Hodgdon, Barbara; Worthen, W. B. (eds.). A Companion to Shakespeare and Performance. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 249–266. ISBN 978-1-4051-8821-0.

- Jackson, Russell, ed. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge Companions to Literature (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521866006. ISBN 978-1-139-00143-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Forsyth, Neil (2007). "Shakespeare the illusionist: filming the supernatural". In Jackson, Russell (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge Companions to Literature (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–302. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521866006.017. ISBN 978-1-139-00143-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Kliman, Bernice; Santos, Rick (2005). Latin American Shakespeares. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-4064-8.

- Lanier, Douglas (2002). Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture. Oxford Shakespeare Topics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818706-6.

- Loomis, Edward Alleyn (1956). "Master of the Tiger". Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 7 (4): 457. doi:10.2307/2866386. eISSN 1538-3555. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2866386.

- Maskell, D. W. (1971). "The Transformation of History into Epic: The Stuartide (1611) of Jean de Schelandre". The Modern Language Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 66 (1): 53–65. doi:10.2307/3722467. eISSN 2222–4319 Check

|eissn=value (help). ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 3722467. - Muir, Kenneth (1985). Shakespeare: Contrasts and Controversies. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1940-3.

- Nagarajan, S. (1956). "A Note on Banquo". Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 7 (4): 371–376. doi:10.2307/2866356. eISSN 1538-3555. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2866356.

- Orgel, Stephen (2002). The Authentic Shakespeare. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91213-X.

- Palmer, J. Foster (1886). "The Celt in Power: Tudor and Cromwell". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Royal Historical Society. 3 (3): 343–370. doi:10.2307/3677851. eISSN 1474-0648. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3677851.

- Pasternak, Boris (1959). I Remember: Sketch for an Autobiography. Translated by Magarshack, David; Harari, Manya. New York: Pantheon Books. OL 6271434M.

- Paul, Henry Neill (1950). The Royal Play of Macbeth: When, Why, and How It Was Written by Shakespeare. New York: Macmillan. hdl:2027/mdp.39015012064237. OCLC 307817. OL 6084940M.

- Perkins, William (1610). A Discovrse of The Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge University Press. OL 19659796M.

- Price, Eoin (2014). Edmondson, Paul; Prescott, Paul (eds.). "Macbeth in Original Pronunciation (Shakespeare's Globe) @ Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, 2014". Reviewing Shakespeare. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Rogers, H. L. (1965). "An English Tailor and Father Garnet's Straw". The Review of English Studies. Oxford University Press. 16 (61): 44–49. doi:10.1093/res/XVI.61.44. eISSN 1471–6968 Check

|eissn=value (help). ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 513543. - Shaughnessy, Robert, ed. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521844291. ISBN 978-1-139-00152-6 – via Cambridge Core.

- Holland, Peter (2007). "Shakespeare abbreviated". In Shaughnessy, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–45. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521844291.003. ISBN 978-1-139-00152-6 – via Cambridge Core.

- Smith, Joshua S. (2012). "Reading Between the Acts: Satire and the Interludes in The Knight of the Burning Pestle". Studies in Philology. The University of North Carolina Press. 109 (4): 474–495. doi:10.1353/sip.2012.0027. ISSN 1543-0383. S2CID 162251374 – via Project MUSE.

- Spurgeon, Caroline F. E. (1935). Shakespeare's Imagery and What it Tells Us. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511620393. ISBN 978-0-511-62039-3 – via Cambridge Core.

- Stoll, E. E. (1943). "Source and Motive in Macbeth and Othello". The Review of English Studies. Oxford University Press. 19 (73): 25–32. doi:10.1093/res/os-XIX.73.25. eISSN 1471–6968 Check

|eissn=value (help). ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 510055. - Straczynski, J. Michael (2006). Babylon 5. The Scripts of J. Michael Straczynski. 6. Synthetic World.

- Tandon, Aditi (29 June 2004). "Exposing rural Punjabis to Shakespeare magic". The Tribune. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Taylor, Gary; Jowett, John (1993). Shakespeare Reshaped, 1606–1623. Oxford Shakespeare Studies. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812256-2.

- Thomson, Peter (1992). Shakespeare's Theatre. Theatre Production Studies (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05148-7.

- Thrasher, Thomas (2002). Understanding Macbeth. Understanding Great Literature (1nd ed.). San Diego: Lucent Books. ISBN 1-56006-998-8.

- "Theatre workshop for children". The Tribune. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Tritsch, Dina (April 1984). "The Curse of 'Macbeth'. Is there an evil spell on this ill-starred play?". Playbill. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- Walter, Harriet (2002). Actors on Shakespeare: Macbeth. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21407-5.

- King James VI and I (2016). Warren, Brett R. (ed.). The Annotated Dæmonology: A Critical Edition. ISBN 978-1-5329-6891-4.

- Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen, eds. (2003). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Billington, Michael (2003). "Shakespeare and the Modern British Theatre". In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 595–606. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Hawkes, Terence (2003). "Shakespeare's Afterlife: Introduction". In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 571–581. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Tatspaugh, Patricia (2003). "Performance History: Shakespeare on the Stage 1660–2001". In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 525–549. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah, eds. (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4. S2CID 152980428 – via Cambridge Core.

- Gay, Penny (2002). "Women and Shakespearean performance". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 155–173. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.009. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Gillies, John; Minami, Ryuta; Li, Ruru; Trivedi, Poonam (2002). "Shakespeare on the stages of Asia". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 259–283. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.014. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Holland, Peter (2002). "Touring Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–211. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.011. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Marsden, Jean I. (2002). "Improving Shakespeare: from the Restoration to Garrick". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–36. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.002. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Moody, Jane (2002). "Romantic Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–57. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.003. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Morrison, Michael A. (2002). "Shakespeare in North America". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–258. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.013. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- O'Connor, Marion (2002). "Reconstructive Shakespeare: reproducing Elizabethan and Jacobean stages". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–97. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.005. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Schoch, Richard W. (2002). "Pictorial Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–75. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.004. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Smallwood, Robert (2002). "Twentieth-century performance: the Stratford and London companies". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–117. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.006. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Taylor, Gary (2002). "Shakespeare plays on Renaissance stages". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.001. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Williams, Simon (2002). "The tragic actor and Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–136. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.007. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Wells, Stanley; Taylor, Gary, eds. (2005). The Complete Works. The Oxford Shakespeare (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926718-7.

- Whitted, Brent E. (2012). "Staging Exchange: Why The Knight of the Burning Pestle Flopped at Blackfriars in 1607". Early Theatre. 15 (2): 111–130. eISSN 2293–7609 Check

|eissn=value (help). ISSN 1206-9078. JSTOR 43499628. - Wickham, Glynne (1969). Shakespeare's Dramatic Heritage: Collected Studies in Mediaeval, Tudor and Shakespearean Drama. Routledge. OL 22102542M.

- Wills, Garry (1996). Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare's Macbeth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510290-1.

- Zagorin, Perez (1996). "The Historical Significance of Lying and Dissimulation". Social Research. The New School. 63 (3, Truth–Telling, Lying And Self–Deception): 863–912. ISSN 0037-783X. JSTOR 40972318.

External links

| The Wikibook Introduction to Shakespeare has a page on the topic of: The Tragedy of Macbeth |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Macbeth |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Macbeth. |

- Performances and Photographs from London and Stratford performances of Macbeth 1960–2000 – From the Designing Shakespeare resource

- Macbeth at Project Gutenberg

- "Macbeth" Complete Annotated Text on One Page Without Ads or Images

- Macbeth at the British Library

- Macbeth on Film

- PBS Video directed by Rupert Goold starring Sir Patrick Stewart

- Annotated Text at The Shakespeare Project – annotated HTML version of Macbeth

- Macbeth Navigator – searchable, annotated HTML version of Macbeth

Macbeth public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Macbeth public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Macbeth Analysis and Textual Notes

- Annotated Bibliography of Macbeth Criticism

- Macbeth – full annotated text aligned to Common Core Standards

- Shakespeare and the Uses of Power by Stephen Greenblatt

.png.webp)