Malik Kafur's invasion of the Pandya kingdom

During 1310-1311, the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji sent an army led by Malik Kafur to the southernmost kingdoms of India. After subjugating the Hoysalas, Malik Kafur invaded the Pandya kingdom (called Ma'bar in Muslim chronicles) in present-day Tamil Nadu, taking advantage of a war of succession between the Pandya brothers Vira and Sundara. During March–April 1311, he raided several places in the Pandya territory, including their capital Madurai. He was unable to make the Pandya king a tributary to the Delhi Sultanate, but obtained a huge plunder, including elephants, horses, gold and precious stones.

Background

By 1310, Alauddin Khalji of the Delhi Sultanate had forced the Yadava and Kakatiya rulers of Deccan region in southern India to become his tributaries. During the 1310 Siege of Warangal against the Kakatiyas, Alauddin's general Malik Kafur had learned that the region to the south of the Yadava and Kakatiya kingdoms was also very wealthy. After returning to Delhi, Kafur told Alauddin about this, and obtained permission to lead an expedition to the southernmost regions of India.[1]

In early 1311, Malik Kafur reached Deccan with a large army. In February, he besieged the Hoysala capital Dwarasamudra with 10,000 soldiers, and forced the Hoysala king Ballala to become a tributary of the Delhi Sultanate. He stayed at Dwarasamudra for 12 days, waiting for the rest of his army to arrive at Dwarasamudra.[2]

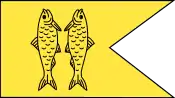

At this time, the Pandya kingdom, located to the south of the Hoysala territory, was in a state of political turmoil. After the death of the king Maravarman Kulashekhara, his sons Vira and Sundara Pandya were engaged in a war of succession.[3] Some later chroniclers state that Sundara sought Malik Kafur's help, leading to the Delhi army's invasion of the Pandya territory. However, the writings of the contemporary writer Amir Khusrau cast doubt on this claim: Khusrau's account suggests that Malik Kafur raided the territories controlled by both of them.[2]

Khusrau describes Sundara Pandya as a Brahman, who was a "pearl" among the Hindu kings. He states that Sundara, whose rule extended over land and sea, had a large army and several ships.[4]

March to the Pandya country

Malik Kafur started his march towards the Pandya territory (called Ma'bar in Muslim chronicles) from Dwarasamudra on 10 March 1311, and reached the Pandya frontier five days later.[2] The Delhi courtier Amir Khusrau mentions that, during this march, the Delhi army covered a difficult terrain, where sharp stones tore horse hoofs, and the soldiers had to sleep on ground "more uneven than a camel's back" at night.[5]

According to the 14th century chronicler Isami, the defeated Hoysala King Ballala guided the Delhi army during the plunder of the Pandya territories.[5] However, historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena doubts this claim, as it does not appear in the contemporary writings of Khusrau.[2]

Isami states that the Delhi army relied on a reconnaissance unit to explore the Pandya territory. This unit included leading generals such as Bahram Kara, Katla Nihang, Mahmud Sartiha, and Abachi. Every day, one of these generals would lead the reconnaissance party to visit an area of the Pandya territory, supported by a few people who knew the local language. One day, Abachi, who was a Mongol commander, decided to join the Pandya service, and even thought of killing Kafur. He got in touch with some people who promised to take him to the Pandya king.[5] While marching towards the Pandya king's residence, his contingent came into conflict with a body of Pandya troops.[6] Abachi asked his interpreter to communicate his intent to the Pandya troops, but the Pandya contingent suddenly attacked them and the interpreter was killed by an arrow.[7] Abachi had to retreat and rejoin Malik Kafur. When Malik Kafur came to know about Abachi's activities, he had Abachi imprisoned.[6] Later, Alauddin had Abachi executed in Delhi, which prompted Mongol nobles to conspire against him, ultimately leading to the 1311 massacre of Mongols.[8]

Khusrau states that the Pandya territory was protected by a high mountain, but there were two passes on either side of the mountain. He names these passes as Tarmali and Tabar, which can be identified with Tharamangalam and Thoppur. The Delhi army marched through these passes, and then encamped on the banks of a river (probably Kaveri). Next, the invaders captured a fort, which Khusrau calls "Mardi". According to Banarsi Prasad Saksena, Khusrau uses "Mardi" as an antonym of "namardi" (Persian for "impotence"), to characterize the fort's defenders.[2] The Delhi army massacred the inhabitants of Mardi.[6]

Raids

Birdhul

Next, Malik Kafur marched to Vira Pandya's headquarters, called "Birdhul" by Amir Khusrau. This is same as "Birdaval", which is named as the capital of the Ma'bar country (the Pandya territory) in Taqwīm al-buldān (1321), a book by the Kurdish writer Abu'l-Fida. British scholar A. Burnell identified Birdhul as Virudhachalam.[6] According to Mohammad Habib and Banarsi Prasad Saksena, who transliterate the name as "Bir-Dhol" (or "Vira-Chola"), the term may be a figure of speech invented by Khusrau to refer to the capital of Vira Pandya.[4] It can be derived from the words "Bir" (Vira) and "Dhol" (drum), thus equivalent to "the drum (capital) of Vira Pandya".[2] While describing Malik Kafur's entry into the city, Khsurau states "the Bir (Vira) had fled, and the Dhol (Drum) was empty".[4]

Owing to the war between the two brothers, the Pandya forces were not in a position to offer much resistance. Vira Pandya originally planned to flee to an island, but was unable to do so for some reason. Instead, he first marched to Kabam, a city whose identity is uncertain. He collected some soldiers and wealth from Kabam, and then escaped to Kandur[4] (identified with Kannanur on the banks of the Kollidam River).[9]

At Birdhul, the Delhi army found a contingent of around 20,000 Muslim soldiers in the Pandya service. These soldiers deserted the Pandyas, and joined the Delhi army.[6] Instead of killing them for being apostates, the Delhi generals decided to spare their lives.[4]

With help of the Muslim deserters, the Delhi army tried to pursue Vira Pandya, but had to retreat because of heavy rainfall.[10] According to the Khusrau, the rural areas were so flooded that "it was impossible to distinguish a road from a well". A large part of the Delhi army encamped at Birdhul, while a small party went out in search of Vira Pandya despite the heavy rains. At midnight, the unit brought the news that Vira Pandya was at Kannanur.[4]

Kannanur

The Delhi army marched to Kannanur in heavy rains, but by this time, Vira had escaped to a forest with some of his followers. When the rains stopped, the invaders captured 108 elephants loaded with pearls and precious stones.[9] They massacred the residents of Kannanur.[10]

The Delhi generals wanted to find Vira Pandya, so that they could force him into becoming a tributary to the Delhi Sultanate. They suspected that Vira Pandya had fled to his ancestral fort of Jal-Kota ("water fort", identified with Tivukottai). They started marching towards Jal-Kota, but people coming from that place informed them that he was not there. Ultimately, the Delhi generals decided that finding Vira Pandya was a hopelessly difficult task, and decided to return to Kannanur.[9]

Barmatpuri

According to Khusrau, the next morning, the Delhi army learned that the town of Barmatpuri had a golden temple, with several royal elephants roaming around it. S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar identified Barmatpuri as "Brahmapuri" (Chidambaram), whose Nataraja Temple had a golden ceiling.[9]

The Delhi army reached Barmatpuri at midnight, and captured 250 elephants the next morning. The invaders then plundered the golden temple, whose ceiling and walls were studded with rubies and diamonds.[9] They destroyed all the Shiva lingams (called "Ling-i-Mahadeo" by Khusrau), and brought down an idol of Narayana (Vishnu).[11] Khusrau mentions that the ground that once smelled of musk now emitted a stench of blood.[9]

Madurai

From Barmatpuri, the Delhi army marched back to its camp at Birdhul, where it arrived on 3 April 1311.[9] There, the invaders destroyed the temple of Vira Pandya. The Delhi forces then arrived Kanum (identified with Kadambavanam) on 7 April 1311. 5 days later, they reached Madurai (called "Mathura" by Khusrau), the capital of Sundara Pandya.[12]

By this time, Sundara Pandya had already fled the city with his queens. The Delhi army first visited the temple of "Jagnar", hoping to find elephants and treasures there. (H. M. Elliot translated "Jagnar" as "Jagannatha", but historian S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar identifies "Jagnar" as "Chokkanatha", an aspect of Madurai's patron deity Shiva.) Malik Kafur was disappointed to find that only 2-3 elephants were left at the temple. This made him so angry, that he set fire to the temple.[12][13]

Rameshwaram

According to the 16th-17th century chronicler Firishta, Malik Kafur built a mosque called Masjid-i-Alai ("Alauddin's mosque"), which could still be seen during Firishta's time, at a place named "Sit Band Ramisar". This place has been identified as "Setubandha Rameshwaram", leading to suggestions that Malik Kafur raided Rameshwaram. However, this identification is doubtful, as Firishta places this mosque in the "Carnatik" country at the port of "Dur Samandar" on the shore of the "Sea of Ummam", and states that it was built after Kafur subjugated the local ruler Bikal Dev. The "Sea of Ummam" (Sea of Oman) refers to the Arabian Sea, and therefore, the mosque must have been located at a port on this sea, in the Hoysala kingdom, whose capital was Dwarasamudra ("Dur Samandar") in present-day Karnataka. Therefore, it is likely that "Sit Band Ramisar" does not refer to Rameshwaram.[14]

The writings of Amir Khusrau or Ziauddin Barani do not contain any reference to Rameshwaram, and Firishta's account may be the result of a confusion.[14] Had Malik Kafur really constructed a mosque in Rameshwaram, Alauddin's courtier Khusrau would not have failed to mention such an achievement. If a mosque existed at Rameshwaram during Firishta's lifetime, it must have been built after the Khalji period.[12]

Although the identification of Firishta's "Sit Band Ramisar" with Rameshwaram is dubious, it is not unlikely that Malik Kafur's forces marched to Rameshwarm from Madurai, in search of the much-sought elephants and Pandya wealth. According to Amir Khusrau's Ashika, during a campaign against a ruler called "Pandya Guru", the Khalji forces reached as far as "the shores of the sea of Lanka". The capital of this ruler was called "Fatan", and had a temple with an idol. "Fatan" may be a transcription of "Periyapattinam", the name of a place near Rameshwaram.[14]

Return to Delhi

Lilatilakam, a 14th-century Sanskrit treatise written by an unknown author, states that a general named Vikrama Pandya defeated the Muslims. Based on this, some historians believe that Vikrama Pandya, an uncle of Vira and Sundara, defeated Malik Kafur's army. However, the identification of this Vikrama Pandya as the brother of Maravarman Kulashekhara is not supported by historical evidence. The Vikrama Pandya mentioned in Lilatilakam appears to have defeated another Muslim army during 1365-70 as a prince; he ascended the Pandya throne much later, in 1401.[15]

By late April 1311, the rains had obstructed the operations of the Delhi forces, and the generals received the news that the defenders had assembled a large army against them.[16] Kafur, who had already collected a huge amount of wealth from Hoysala and Pandya kingdoms, determined that it was futile to pursue the Pandya king. Therefore, he decided to return to Delhi.[17] According to Alauddin Khalji's courtier and chronicler Amir Khusrau, the Delhi army had captured 512 elephants, 5,000 horses and 500 manns of gold and precious stones by the end of its southern campaign against the Hoysalas and the Pandyas.[12] According to the exaggerated account of the later writer Ziauddin Barani (a less reliable writer who wrote during the Tughluq era), the loot included 612 elephants; 20,000 horses; and 96,000 manns of gold. Barani describes this seizure of wealth as the greatest one since the Muslim capture of Delhi.[18]

The army started its return journey on 25 April 1311. In Delhi, Alauddin held a public court (darbar) at Siri on 19 October 1311, to welcome Malik Kafur and other officers of the army.[12] He gave 0.5 to 4 manns of gold to his various nobles and Amirs.[18]

Aftermath

After Kafur's departure, the Pandya brothers resumed their conflict. This conflict resulted in the defeat of Sundara Pandya, who decided to seek Alauddin's assistance. With help of Alauddin's forces, he was able to re-establish his rule in the South Arcot region by 1314. Later, during the reign of Alauddin's son Qutb ud din Mubarak Shah, the Delhi general Khusro Khan raided the Pandya territories. The northern part of the Pandya kingdom was captured by the Muslims over the next two decades: it first came under the control of the Tughluq dynasty, and later became part of the short-lived Madurai Sultanate. However, the southernmost part of the Pandya territory remained independent.[16]

References

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 201.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 414.

- B. R. Modak 1995, p. 3.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 415.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 207.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 208.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 418.

- Peter Jackson 2003, p. 174.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 416.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 209.

- Richard H. Davis 1999, p. 113.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 417.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, pp. 209-212.

- Mohammad Habib 1981, p. 416.

- K.K.R. Nair 1987, p. 27.

- Peter Jackson 2003, p. 207.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 212.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 213.

Bibliography

- B. R. Modak (1995). Sayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-940-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Alauddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 31870180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mohammad Habib (1981). Politics and Society During the Early Medieval Period. People's Publishing House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- K.K.R. Nair (1987). "Venad: Its Early History". Journal of Kerala Studies. University of Kerala. 14 (1): 1–34. ISSN 0377-0443.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. OCLC 685167335.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richard H. Davis (1999). Lives of Indian Images. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00520-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)