Mallet locomotive

The Mallet locomotive is a type of articulated steam railway locomotive, invented by the Swiss engineer Anatole Mallet (1837–1919).

The articulation was achieved by supporting the front of the locomotive on an extended Bissel truck. The compound steam system fed steam at boiler pressure to high-pressure cylinders driving the main set of wheels. The exhaust steam from these cylinders was fed into a low-pressure receiver and was then sent to low-pressure cylinders that powered the driving wheels on the swiveling bogie.

Compounding

Steam under pressure is converted into mechanical energy more efficiently if it is used in a compound engine; in such an engine steam from a boiler is used in high-pressure (HP) cylinders and then under reduced pressure in a second set of cylinders. The lower-pressure steam occupies a larger volume and the low-pressure (LP) cylinders are larger than the high-pressure cylinders.

A third stage (triple expansion) may be employed. Compounding was proposed by the British engineer Jonathan Hornblower in 1781.

The American engineer W. S. Hudson patented a system of compounding for railway locomotives in 1873[1] in which he proposed an intermediate receiver surrounded by hot gas from the fire, so that the low-pressure steam is partly superheated.

Mallet himself proposed cross-compounding in which a conventional steam locomotive configuration would have one high-pressure cylinder and one low-pressure cylinder.[2]

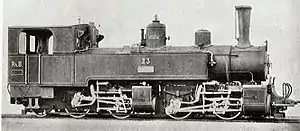

Mallet patented such a system in 1874, and in 1876 the first locomotive on his principle was built: an 0-4-2T for the Bayonne and Biarritz Railway, and several others followed for railways in mainland Europe.[3]

The London and North Western Railway locomotive engineer F W Webb adopted the idea and converted some existing locomotives in 1879, followed by de Glehn and others in the 1880s and several American engineers in the 1890s which included some vertical boiler railcar applications.[3]

Articulation

Mallet found typical main line railways unwilling to adopt his particular ideas and, in 1884, he started to propose compounding combined with articulation; on lightly engineered secondary lines this could give greater power to locomotives whose axle load and size was limited. His patent 162876 in France specified four cylinders, two large and two small, with one pair of cylinders acting on two or three fixed axles, and the other pair acting on axles mounted in a swivelling truck.[3]

Diagrams provided by Mallet make it clear that the swivelling truck was to be a Bissell truck, that is, a pony truck or bogie pivoting about a vertical pin some distance behind the centre of the truck itself. The weight of the front part of the boiler was to be supported on an arc-shaped radial bearing. The truck could therefore turn into a curve and move to some extent laterally. Typically the support bearing was placed beneath the smokebox, hollowed and with a sliding seal to provide a route for exhaust steam from the low-pressure cylinders to discharge through a blastpipe within the smoke box.

Mallet considered that the major advantage of this arrangement was that it enabled the cylinders on the truck to be fed with low-pressure steam: the high-pressure cylinders were on the fixed main frame and only low-pressure steam needed to be carried through movable pipes to the swivelling truck.

The Mallet concept

This then was what became understood as a "Mallet" locomotive: an articulated locomotive in which the rear set of driving wheels were fixed in the main frame of the locomotive; a Bissell truck carrying a second set of driving wheels; and compounding in which the high-pressure cylinders drove the axles on the main frame and the Bissell truck axles were driven by low-pressure steam.

Mallet asserted that the advantages of his concept were:

- all the locomotive weight would be adhesive, yet there would be great flexibility of the locomotive as a vehicle;

- the difficulties with Meyer, Fairlie and other then-existing articulated systems would be eliminated as the moving pipes would be carrying low-pressure steam at only 40 to 55 psi (280 to 380 kPa) pressure, and would be easier to keep steam-tight; and

- A simple type of very powerful locomotive would be created.[3]

The large-diameter pipe conveying the low-pressure steam from the high-pressure to the low-pressure cylinders acted also as a receiver, forming a buffer for the gas flow.

Independent cut-offs for the high-pressure and low-pressure cylinders were advocated by Mallet, but driving standards were inadequate and he later used combined cut-off control.

European versions

Large numbers of Mallet designs for narrow gauge railways were built, but in 1889 the first six standard gauge examples were built by J A Maffei for the Swiss Central railways, and an 87 tonne 0-6-6-0T banker (US: pusher) for the Gotthard Bahn, the last being the most powerful and heaviest locomotive in the world at the time. By 1892 110 Mallets were at work, of which 24 were standard gauge; by 1900 there were nearly 400, of which 218 were on standard gauge or Russian gauge (1,520 mm (4 ft 11 27⁄32 in)).

One of the examples in Germany were the 0-8-8-0Ts built by Maffei for Bavarian State Railways between 1913 and 1923. However no Mallet ever ran on a British railway.

Mallet designs were popular in Hungary, too. 30 of MÁV 422 (B'B) were built between 1898–1902 (the last one served until 1958). MÁV 401 was a (1B)B locomotive in service between 1905–1969 and MÁV 651 (C'C) until 1962. The strongest Mallet-locomotive of Europe was the MÁV 601 which was built for the Hungarian State Railways, it as a (1'C)C type steam locomotive. With their 22.5 meter length, 163.3 tonnes total weight and 2200 KW power, the MÁV 601 was the biggest, the heaviest and most powerful steam locomotive built before and during the First World War in Europe.[4]

North American versions

.jpg.webp)

The first Mallet locomotive in the United States was Baltimore & Ohio Railroad number 2400, built by Alco in 1904. Nicknamed "Old Maude", it was a 0-6-6-0 weighing 334,500 lb (151,700 kg) and with axle loads of 60,000 lb (27,000 kg).[5] Received negatively at first due to speed limitation arising from the short wheelbase and stiff suspension, it gained support during service, and it was soon followed by Baldwin examples, and then steadily heavier and more powerful successors.

In Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway experimented with an unusual design of Mallet promoted by H.H. Vaughan, then Chief Mechanical Officer and Assistant to the CPR Vice-President. Their in-house compound 0-6-6-0 design located both the high and low pressure cylinders adjacent to one another in the center of the locomotive driving opposite directions. Produced in the CPR's Angus shops, road numbers 1950 to 1954 were outshopped between 1909 and 1911. An additional "simple" (as opposed to compound) unit with road #1955 featuring the same arrangement was also produced. These were used in helper service in the Rockies and Selkirks. The units were unpopular with crews owing to frequent steam leakages and derailments resulting from the lack of pilot wheels. While not an outright failure these were considered an unsuccessful design, and by 1916-1917 these units had been converted to a conventional 2-10-0 arrangement. These six locomotives were ultimately the only articulated locomotives operated by a Canadian railway.

As weight and power and length increased, there were experiments with flexible boiler casings; from 1910 the Santa Fe road introduced 2-6-6-2 locomotives weighing 392,000 lb (178,000 kg), with a 37 feet (11.28 m) long boiler barrel, with a firetube reheater and a firetube feedwater section in front, each separated by a blank section, and variants of a telescopic or bellows type boiler casing.[6] These were unsuccessful, and later engines used conventional boilers.

The largest compound Mallets were ten 2-10-10-2s built for the Virginian by Alco in 1918; in pairs they pushed coal trains headed by a 2-8-8-2.[7]

Although compounds had been considered obsolescent since the 1920s, C&O thought them appropriate, in the late 1940s, for low-speed coal-mine pickup runs converging on the classification yard at Russell, Kentucky.[8] Only ten were built before the order was cancelled, the last delivered in September 1949. The final loco, Chesapeake and Ohio 1309, is preserved on the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad.[9] The 1309 was also the last steam locomotive that Baldwin built for the North American market.

The last compound Mallets to remain in use on a major North American railroad were the N&W class Y6b 2-8-8-2 locomotives, retired in July 1959. Norfolk & Western 2156 is the sole surviving Y6b, preserved at the Museum of Transportation in St. Louis.

Simple expansion versions in the US

By about 1920 the US version of the Mallet as a huge slow-speed pusher had reached a plateau; the size of the LP cylinders became a limiting factor even on the large loading gauge permitted in the US, and reciprocating masses posed serious dynamic problems above walking pace. Moreover, there were adhesion stability problems where the front engine tended to slip and then stall uncontrollably because of an imbalance of tractive effort and axle load, accentuated by the drawbar reaction, and inability of the intermediate steam receiver to accommodate the sudden pressure change. This was further worsened by dynamic instability of the front end in running.

The Chesapeake & Ohio road introduced 25 simple (non-compound expansion) 2-8-8-2 locomotives in 1924 and 20 more in 1926. Although the simple-expansion concept diverged from Mallet's original patent, the locomotives were clearly a continuation of the concept and were conveniently still referred to as "Mallet" locomotives. As the front truck cylinders were now using boiler pressure steam, special arrangements were necessary to deliver it, through the truck pivot pin where only radial movement took place. These new locomotives took over service on a 113-mile (182 km) division, covering it in 5 hours with 9,500 short tons (8,600 t; 8,500 long tons) and a single locomotive.[3]

Further development culminated in 1941 with the 4-8-8-4 Big Boy type on the Union Pacific RR. They weighed 760,000 to 772,000 lb (345,000 to 350,000 kg) with a 434,000 lb (197,000 kg) tender; at 133 feet (40.54 m) long (including the tender), they could only be turned on a select few of the system's turntables. They could develop 6,290 horsepower (4,690 kW) on the drawbar at 35 mph (56 km/h) and were designed for a top speed of 70 mph (110 km/h), though they rarely saw these speeds during their service careers. Slightly shorter but even heavier and more powerful were 2-6-6-6s built by Lima for the C&O and the Virginian between 1941 and 1948, which weighed 778,000 lb (353,000 kg) and could produce up to 6,900 horsepower (5,100 kW) at 45 mph (72 km/h).

The last Mallets

These US locomotives were paralleled to some extent by heavy haul versions in the USSR, though without any attempt at faster running. Two 2-8-8-4 examples built in Russia in 1954–55 were probably the last Mallets built in Europe.[3]

Other continents

Although it had found early favour in Europe, especially on lightly engineered railways, the Mallet type had generally been superseded by the Garratt locomotive by the mid-1920s, but in the Dutch East Indies, now the Republic of Indonesia, several types and sizes remained in use into the 1980s. Moreover, in 1962 the Indonesian State railways DKA ordered a series of 0-4-4-2s, basically an updated version of the earlier Dutch design, for the old Atjeh (now Aceh) tramway. Constructed by Nippon Sharyo in Japan, these are the only Mallets built in Asia. In contrast to the rest of the Indonesian railways it has a gauge of 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in), as to 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) for the rest of the Archipelago. Smaller Mallets were used by plantations and other industries, all of the 0-4-4-0 type. These ran mostly on 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) and 700 mm (2 ft 3 9⁄16 in) gauge networks. They were employed in Brazilian 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge, tight-radius railroads.

One Mallet ran in New Zealand, and is preserved at Glenbrook Vintage Railway, Auckland. Three Mallets ran in Australia, including one on the Magnet Tramway in Tasmania.

Preservation

Several Mallets have been preserved, some in operational condition. A number of the Union Pacific "Big Boys", are preserved, including one overlooking Omaha, Nebraska where UP is based. In January 2014, Big Boy #4014 was removed from its museum ground parking track in Pomona, California and hauled to Cheyenne, Wyoming for restoration to operating condition; this was completed in May 2019. No. 4014 is the largest, heaviest, and most powerful operational steam locomotive in the world.

Two of Union Pacific's "Challengers" class have also survived into preservation. Challenger #3985 was the largest operational steam locomotive in the world until the restoration of UP 4014. It was taken out of service in October 2010 due to mechanical problems and subsequently retired in January 2020.

Chesapeake & Ohio 2-6-6-2 #1309, the last domestic steam locomotive built by Baldwin, was scheduled for restoration in September 2017. "New as they were, the last C&O steam engines never got adequate maintenance, lengthening the list of work needed to bring 1309 back to life." https://wmsr.com/1309-restoration/ Although restoration is not 100% complete (as of 1/15/2021), C&O 1309 was fired up and moved under her own steam on December 31, 2020, the 1st time she had done so in 64 years. The C&O 1309 is scheduled to be fully complete and in operation for the upcoming 2021 tourist season.

The single surviving example of a Cab forward Mallet is Southern Pacific 4294, which is on display at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento, California.

Several smaller loggin railroad Mallets have been restored to operating condition, including 2-6-6-2T Black Hills Central #110 in Hill City, South Dakota, 2-6-6-2T Clover Valley Lumber Company #4 in Sunol, California,[11] and 2-4-4-2 Deep River Logging "Skookum" #7 in Garibaldi, Oregon.

One of the early Dutch-built Indonesian Mallets has been returned to the Netherlands and is now exhibited in the Dutch Railway Museum,[12]

Another industrial type has been purchased and restored by the Statfold Barn Railway in the UK. This saw its first operation in Europe in 2011 and after initial trials on the owners' railway, was transferred to the Welsh Highland Railway as its power is better suited to that railway.

A number of Mallets were constructed for the Nordhausen Wernigerode Eisenbahn, now part of the Harz Narrow Gauge Railways system in Germany. Running numbers 99 5901-3 and 99 5906 are in working order.

ABPF-SC (Brazilian Association for Railroad Preservation – Santa Catarina branch) has restored a 2-6-6-2 Mallet to working order. It hauls tourist steam trains on 3% grades. The first official train ran on April 30 2017.

Terminology

As a French-speaking Swiss, Mallet pronounced his name accordingly, something like "Ma-lay".

Mallet's original patent specifies compound expansion, but after his death in 1919 many locomotives (particularly in the United States) were articulated Mallet style without using compounding (for instance the Union Pacific Big Boy). When fleets of such locomotives appeared in the middle 1920s the trade press naturally called them "Simple Mallets" — i.e., simple locomotives articulated like Mallets — but eventually the notion spread that this was somehow incorrect. The term "Mallet" continued to be widely used for simples as well as compounds, but some enthusiasts insist "simple Mallet" is an oxymoron.[13]

- Examples of Mallet locomotives

2-6-6-2T Mallet #110, Black Hills Central Railroad, USA

2-6-6-2T Mallet #110, Black Hills Central Railroad, USA 2-6-6-2 Restored Mallet #204, ABPF, Rio Negrinho, Santa Catarina, Brazil

2-6-6-2 Restored Mallet #204, ABPF, Rio Negrinho, Santa Catarina, Brazil A 2-6-6-2 Mallet Locomotive at the Northwest Railway Museum in Snoqualmie, Washington

A 2-6-6-2 Mallet Locomotive at the Northwest Railway Museum in Snoqualmie, Washington Portuguese Railways Mallet locomotive No. E168 at Povoa da Varzim, August 1970

Portuguese Railways Mallet locomotive No. E168 at Povoa da Varzim, August 1970 Swedish-built Mallet locomotive DONJ No 12 in Jädraås, Sweden, August 2009

Swedish-built Mallet locomotive DONJ No 12 in Jädraås, Sweden, August 2009 Russian Mallet locomotive Fita (Ө) series in 1905. Note piston valves on high-pressure cylinders and slide valves on low-pressure cylinders

Russian Mallet locomotive Fita (Ө) series in 1905. Note piston valves on high-pressure cylinders and slide valves on low-pressure cylinders.jpg.webp) "Union Pacific Big Boy", an example of a simple Mallet. This type is generally regarded as the largest steam locomotive in the world.

"Union Pacific Big Boy", an example of a simple Mallet. This type is generally regarded as the largest steam locomotive in the world. Harz Narrow Gauge Railways 99 5901

Harz Narrow Gauge Railways 99 5901

References

- US Patent 136729, Improvement in Locomotives, March 11, 1873

- Mallet, A, On the Compounding of Locomotive Engines, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, London, June 1879, page 328, quoted in The Steam Engine: A Treatise on Steam Engines and Boilers, Clark, D K, Blackie and Co, London

- Loco Profile 6: The Mallets, Reed, Brian, Profile Publications Limited, Windsor, undated

- (Béla Czére, Ákos Vaszkó): Nagyvasúti Vontatójármüvek Magyarországon, Közlekedési Můzeum, Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat, Budapest, 1985, ISBN 9635521618

- Ransome-Wallis, P. (1959). Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Railway Locomotives (2001 republication ed.). Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 500–501. ISBN 0-486-41247-4.

- Self, Douglas. "Flexible-Boiler Mallet Locomotives". Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Llanso, Steve. "Virginian 2-10-10-2 Locomotives of the USA". www.steamlocomotive.com. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- "Locomotive Notes," Trains magazine, August 1948

- "Chesapeake & Ohio / Hocking Valley 2-6-6-2 "Mallet Mogul" Locomotives in the USA". www.steamlocomotive.com.

- "Steam Locomotive #110 :: 1880 Train :: 2018 Season". www.1880train.com.

- "Clover Valley Lumber #4". Niles Canyon Railway. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "Het Spoorwegmuseum Loc SSJ 1622". www.nmld.locaalspoor.nl. Netherlands Railway Museum.

- "A Big Boy is Not a Mallet". Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mallet locomotives. |