Maravar

Maravar (also known as Maravan and Marava) are a Tamil community in the state of Tamil Nadu. These people are one of the three branches of the Mukkulathor confederacy.[1] Members of the Maravar community often use the honorific title Thevar.[2][3][4]

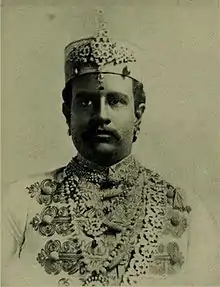

Bhaskara Sethupathi, former Marava ruler of Ramnad kingdom | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India: Ramnad, Madurai, Tirunelveli regions of Tamil Nadu | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kallar, Agamudayar, Tamil people |

The Sethupathi rulers of the erstwhile Ramnad kingdom were from this community.[5] The Maravar community, along with the Kallars, had a reputation for thieving and robbery from as early as the medieval period.[6][7][8][9][10]

Etymology

The term Maravar has diverse proposed etymologies;[11] it may come simply from a Tamil word maram, meaning such things as vice and murder.[12] or a term meaning "bravery".[13]

Social status

According to Pamela G, Price, the Maravar were warriors who were in some cases zamindars. During the British colonial era, the Maravars were sometimes recorded as Kshatriyas by the legal officers involved in Zamindari litigation proceedings but more often they classified as Shudras. Occasionally the Setupathis had to respond to the charge they were not ritually pure.[14]

During the formation of Tamilaham, the Maravars were brought in as socially outcast tribes or traditionally as lowest entrants into the shudra category. The Maravas to this day are feared as a thieving tribe and are an ostracised group in Tirunelveli region.[15][16]

See also

References

- Dirks, Nicholas B. (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-47208-187-5.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-52154-885-4.

- Hardgrave, Robert L. (1969). The Nadars of Tamilnad: The Political Culture of a Community in Change. University of California Press. p. 280.

- Pandian, Anand (2009). Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India. Duke University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-82239-101-2.

- Pamela G. Price (14 March 1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press, 14-Mar-1996 - History - 220 pages. p. 26. ISBN 9780521552479.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Women and Work in Precolonial India: A Reader. Sage Publications. p. 74. ISBN 9789351507406.

- Dirks, Nicholas (2007). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780472081875.

- Balasubramanian, R (2001). Social and Economic Dimensions of Caste Organisations in South Indian States. University of Madras. p. 88.

- Oscar Salemink, Peter Pels (2002). Colonial Subjects. Wiesbaden. p. 160. ISBN 0472087460.

- Ferro-Luzzi, Gabriella Eichinger (2002). The Maze of fantasy in Tamil folktales. Wiesbaden. p. Glossary. ISBN 9783447045681.

- VenkatasubramanianIndia, T. K. (1986). Political Change and Agrarian Tradition in South India, C. 1600-1801: A Case Study. Mittal Publications. p. 49.

- Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Taylor and Francis. p. 213.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8108-5379-9.

- Price, Pamela (1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. University of Cambridge. p. 62.

- Ramasamy, Vijaya (2016). Women and work in Precolonial India. SAGE. p. 62.

- Parkin, Robert (2001). Perilous Transactions. Sikshasandhan. p. 130.