Margery Wentworth

Margery Wentworth, also known as Margaret Wentworth, and as both Lady Seymour[1] and Dame Margery Seymour[2] (c. 1478[3] – 18 October 1550[4]). She was the wife of Sir John Seymour and the mother of Queen Jane Seymour, the third wife of King Henry VIII of England. She was the grandmother of King Edward VI of England.

Margery Seymour | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1478 |

| Died | 18 October 1550 (aged 71–72) |

| Nationality | English |

| Title | Lady Seymour |

| Spouse(s) | Sir John Seymour |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Sir Henry Wentworth Anne Say |

Family

Margery was born in about 1478, the daughter of Sir Henry Wentworth and Anne Say, daughter of Sir John Say and Elizabeth Cheney.[3][5]

Margery's first cousins, courtiers Elizabeth and Edmund Howard, were parents to an earlier and later royal wife than her daughter: Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, respectively.[6][7]

Elizabeth Cheney's first husband was Frederick Tilney, father of Elizabeth Tilney, Countess of Surrey.[5] This made Anne Say although not of peerage-level nobility herself, the half-sister of a countess.[8] Wentworth was also a descendant of King Edward III, this remote royal ancestry is partly why Henry VIII found Jane Seymour (her daughter) marriageable.[9]

Margery's father, Henry Wentworth, rose to be a critical component of Yorkshire and Suffolk politics: in 1489, during the Yorkshire uprising against Henry VII who had married the female main claimant heir of the former Plantagenet dynasty in order to bolster his own shaky claim to the throne, he left his home and was named the steward of Knaresborough, earning him the privilege to keep the peace in the name of the first Earl of Surrey. After this, he was awarded the title of the Sheriff of Yorkshire.[8]

Early life

She was given a place in the household of her aunt, the Countess of Surrey, where she met the poet John Skelton, whose muse she became.[5] She was considered a great beauty by Skelton and others. In poetry dedicated to her he praised her demeanor. Skelton's poem, Garland of Laurel, in which ten women in addition to the Countess weave a crown of laurel for Skelton himself, portrays Margery as a shy, kind girl, and compares her to primrose and columbine. The other nine women from the poem are: Elizabeth Howard, Muriel Howard, Lady Anne Dacre of the South, Margaret Tynley, Jane Blenner-Haiset, Isabel Pennell, Margaret Hussey, Gertrude Statham, and Isabel Knyght.[8]

Marriage and children

On 22 October 1494 Margery married Sir John Seymour (1476 – 21 December 1536)[10] of Wulfhall, Savernake Forest, Wiltshire.[11] On the same day, her father Henry remarried Lady Elizabeth Scrope.[8]

Margery and her husband had ten children together:[11][12]

- John Seymour (died 15 July 1510)[13][14]

- Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of Edward VI (c. 1500[15] – 22 January 1552)[16] married firstly Catherine, daughter of Sir William Filliol[3] and secondly Anne, daughter of Sir Edward Stanhope.[3]

- Sir Henry Seymour (1503–1578) married Barbara, daughter of Morgan Wolfe[17]

- Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley (c. 1508 – 20 March 1549) married Catherine Parr, widow of Henry VIII.[18][19]

- John Seymour (died young)[20]

- Anthony Seymour (died c. 1528)[13][21]

- Jane Seymour, (c. 1509 – 24 October 1537). queen consort of Henry VIII and the mother of Edward VI.[11][22]

- Margery Seymour (died c. 1528)[13][21]

- Elizabeth Seymour (c. 1518[23] – 19 March 1568[24]), married firstly Sir Anthony Ughtred. Married secondly Gregory Cromwell, 1st Baron Cromwell. Her third husband was John Paulet, 2nd Marquess of Winchester.[25]

- Dorothy Seymour[20] married firstly, Sir Clement Smith (c. 1515 – 26 August 1552) of Little Baddow, Essex[14][26] and secondly, Thomas Leventhorpe of Shingle Hall,[27] Hertfordshire.[20][28]

It is presumed that Margery and John had a good relationship in their marriage.[11] After her husband's death, instead of remarrying, she took a larger role in her children's education while running Wulfhall. Notably, her eldest daughter, Jane, was not schooled in a formal setting; Margery instead had her disciplined in more traditional roles that she deemed suitable.[29]

Her son Edward, a soldier and royal servant, would become the Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector. He was the eldest surviving child of the Seymours.[15]

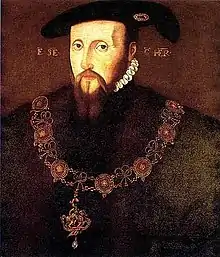

Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, later 1st Duke of Somerset & Lord Protector

Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, later 1st Duke of Somerset & Lord Protector Portrait Miniature of Thomas Seymour, Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger

Portrait Miniature of Thomas Seymour, Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger_-_Jane_Seymour_(Mauritshuis).jpg.webp) Jane Seymour, Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger

Jane Seymour, Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger_-_Portrait_of_a_lady%252C_probably_of_the_Cromwell_Family_formerly_known_as_Catherine_Howard_-_WGA11565.jpg.webp) Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Elizabeth Seymour, Hans Holbein the Younger[23]

Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Elizabeth Seymour, Hans Holbein the Younger[23]

References

- Davey, R. (1909). The Nine Days' Queen, Lady Jane Gray, and Her Times. Methuen & Company, 1909. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

and their mother, Lady Seymour, by birth a Wentworth,....

- "Will of Dame Margery Seymour, Widow - The National Archives, Kew". GOV.UK. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

Will of Dame Margery Seymour, Widow...11 December 1550

- Pollard 1897, pp. 299–310.

- Seymour 1972, p. 340.

- Norton 2009, p. 9.

- Norton 2009, p. 8–9.

- Hart 2010, p. 142.

- Tucker 1969, pp. 333–345.

- Norton 2009, p. 8.

- Aubrey 1862, p. 375–376:"This Knight departed this Lyfe at LX years of age, the XXI day of December, Anno 1536 ..."

- Norton 2009, p. 11.

- Seymour 1972, p. 26.

- Norton 2009, p. 13.

- Aubrey 1862, p. 377.

- Beer 2009.

- Pole 2008, p. 481.

- Hawkyard 1982b.

- Hawkyard 1982c.

- Seymour 1972, p. 65.

- Burke III 1836, p. 201.

- Seymour 1972, p. 35.

- Wagner & Schmid 2012, p. 1000.

- Strong 1967, pp. 278–281: "The portrait should by rights depict a lady of the Cromwell family aged 21 c.1535–40..."

- College of Arms 2012, p. 63.

- Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry III 2011, p. 111–112.

- Machyn 1848, p. 24, 326.

- Shingle Hall is also listed as Shingey, Shingley and Shinglehall in various sources.

- Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry III 2011, p. 82.

- Norton 2009, p. 12–13.

- Acts of the Privy Council III: 1550–1552, p. 142.

References

- Aubrey, John; Jackson, John Edward (1862). Wiltshire: The Topographical Collections of John Aubrey, F. R. S., A. D. 1659–70, With Illustrations. Corrected and enlarged by John Edward Jackson. London: Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society.

- Beer, Barrett L. (January 2009) [First published 2004]. "Seymour, Edward, Duke of Somerset (c.1500–1552)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25159. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Burke, Bernard (1965). Townend, Peter (ed.). Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry. Edited by Peter Townend (18th ed.). London: Burke's Peerage. ASIN B0006BNKM8.

- Burke, John (1836). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Enjoying Territorial Possessions or High Official Rank; But Invested With Heritable Honours. III. London: Published for Henry Colburn by R. Bentley.

- College of Arms (1829) [Printed by S. and R. Bentley, London, 1829]. Catalogue of the Arundel Manuscripts in the Library of the College of Arms. [By William Henry Black. With a preface signed C. G. Y., i.e. Sir Charles George Young]. Rarebooksclub.com (published 20 May 2012). ISBN 9781236284259.

- Dasent, John Roche, ed. (1891) [First published HMSO:1891]. Acts of the Privy Council of England. New Series. III: 1550–1552. British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Davids, R. L. (1982). "Seymour, Sir John (1473/74–1536), of Wolf Hall, Wilts.". In Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hart, Kelly (2010). The Mistresses of Henry VIII. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 9780752462516.

- Hawkyard, A. D. K. (1982). "Cromwell, Gregory (by 1516–51), of Lewes, Suss.; Leeds Castle, Kent and Launde, Leics.". In Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Hawkyard, A. D. K. (1982). "Seymour, Sir Henry (by 1503–78), of Marwell, Hants.". In Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hawkyard, A. D. K. (1982). "Seymour, Sir Thomas II (by 1509–49), of Bromham, Wilts., Seymour Place, London and Sudeley Castle, Glos.". In Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). Members. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509–1558. Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Machyn, Henry (1848). Nichols, John Gough (ed.). The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant–Taylor of London, from A. D. 1550 to A. D. 1563. [Camden Society. Publications]. XLII. Edited by John Gough Nichols. London: Printed for the Camden Society by J. B. Nichols and Son.

- Norton, Elizabeth (2009). Jane Seymour: Henry VIII's True Love (hardback). Chalford: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781848681026.

- Pole, Reginald; Mayer, Thomas F.; Walters, Courtney B. (2008). A Biographical Companion: The British Isles (hardback). The Correspondence of Reginald Pole. 4. By Thomas F. Mayer and Courtney B. Walters. St Andrews Studies in Reformation History. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754603290.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1897). "Seymour, Edward". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 51. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 299–310.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. III (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-1461045205.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. III (2nd ed.). CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1461045137.

- Russell, Gareth (14 May 2010). "May 14th, 1536: Mistress Seymour's New Lodgings". Confessions of a Ci-Devant. Garethrussellcidevant.blogspot.com.au. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Seymour, William (1972). Ordeal by Ambition: An English Family in the Shadow of the Tudors. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0283978661.

- Sherlock, Peter (2008). Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6093-4.

- Strong, Roy (May 1967). "Holbein in England – I and II". The Burlington Magazine. 109 (770): 276–281. JSTOR 875299.

- Tucker, M. J. (Winter 1969). "The Ladies in Skelton's 'Garland of Laurel'". Renaissance Quarterly. 22 (4): 333–345. doi:10.2307/2859042. JSTOR 2859042.