Mary Lawson (actress)

Mary Elizabeth Lawson (30 August 1910 – 6 May 1941[1]) was a stage and film actress during the 1920s and 1930s. In addition to her performances on stage and screen, Lawson was known for her romantic affairs, including with tennis player Fred Perry and her future husband, the married son of the Dame of Sark. Lawson and her husband died in the Second World War during a German bombing raid on Liverpool.

Mary Lawson | |

|---|---|

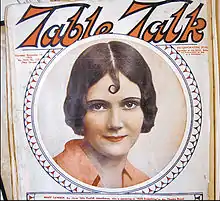

Portrait of Mary Lawson on the cover of the Australian magazine Table Talk from 14 November 1929 | |

| Born | Mary Elizabeth Lawson 30 August 1910 Darlington, County Durham, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 6 May 1941 (aged 30)[1] Liverpool, England, United Kingdom |

| Cause of death | WWII air bombing |

| Other names | Mary Elizabeth Beaumont |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1915–1941 |

| Spouse(s) | Francis William Lionel Collings Beaumont |

Early life

Mary Lawson was born in Darlington, County Durham, England on 30 August 1910.[2][3] She grew up in a humble terraced house on 58 Pease Street on the Freeholders' Estate in Darlington and attended Dodmire School.[3] The Lawsons were a working-class family that had relocated from Gateshead to Darlington several years before Mary's birth. Lawson's father, Thomas Ed Lawson (b. 1876), was an assistant fitter for the North Eastern Railway Company,[3] while her mother, Jane Hood Lawson (b. 1875), died when Mary was only three.[3] As a result, Mary was largely raised by her elder sister Dorothy (b. 1899).[3] Mary also had two brothers: John (b. 1896) and Francis James (b. 1906)

Stage and film career

Lawson began performing at a young age. When she was only five she sang at Feethams for soldiers wounded during the First World War and soon became a regular at Darlington's Scala theatre on Eldon Street.[3] Lawson took on other roles and in 1920 she had a part in a Babes in the Wood panto.[3] At the age of twelve she led a performing group of young girls that toured County Durham for three years.[3] In addition to her pure acting ability, Lawson developed into an exceptional dancer.[2] In her mid-teens she landed a role in a panto in Brighton and later performed in Frinton-on-Sea in Essex, where she was spotted by comedian Gracie Fields.[3] With Fields's support, Lawson was able to become the resident act at The May Fair Hotel in London.[3] Lawson incorporated into her show the song Varsity Drag from the musical Good News, which at the time was being performed by American Zelma O'Neal at the Carlton Theatre in the West End.[2][3][4] Her performance was such a success that when O'Neal returned to the United States, the Carlton Theatre choose 17-year-old Lawson as her replacement.[3] Lawson made her name on stage in 1928 at the Carlton in the role Flo in the production of Good News.[3] In 1929, Lawson departed for Australia on a tour,[3] where she appeared in the productions of The Desert Song and Hold Everything!.[5][6]

By the early 1930s, Lawson had established herself on the stage as a musical comedy star, able to earn fifty to sixty British pounds a week,[3] and in 1933 she entered into the British film industry. Though she eventually acted in more than a dozen films, her screen career never matched her stage success. Her first major role was as Susie in Colonel Blood, which starred Frank Cellier.[7] The most successful film that Lawson had a role in was the 1935 production of Scrooge, which starred Seymour Hicks and Donald Calthrop.[8] She also appeared in films that included in their cast such notable actors as Stanley Holloway in D'Ye Ken John Peel? and Cotton Queen,[9][10] Will Fyffe in Cotton Queen,[10] and Vivien Leigh in Things Are Looking Up,[11] and Bud Flanagan in A Fire Has Been Arranged.[12] Lawson's last film was Oh Boy! in 1938.[13]

Between films she continued her stage career, including a starring role in Life Begins at Oxford Circus at the London Palladium.[3] Lawson appeared in a number of theatrical productions up through the first year of the Second World War. In late 1939 Lawson participated in a series of shows for the benefit of the British military personnel.[14] The last production that Lawson had a role in was White Horse Inn at the Coliseum Theatre in early 1940.[15]

Romances and marriage

Lawson was as known for her off stage romances as she was for her onstage performances. In 1933 her engagement to Maurice Henry van Raalte, heir to a cigar importing fortune, ended tragically with her fiancé's sudden death.[3] In May 1934 Lawson announced she was to marry a Mr H Glendenning, a cameraman on the set of Money in the Air, a film in which Lawson had a part and that was eventually distributed as Radio Pirates.[3][16] But only a few months later in August 1934 Lawson caused a national sensation when it was announced that she was engaged to Fred Perry, the world's premier tennis player and winner of numerous Grand Slam tournaments. The couple first met when Perry visited the London studies of the film Falling in Love, in which Lawson played the role of Ann Brent.[3] Perry later escorted Lawson to an exhibition match at Highbury Fields and proposed marriage before he departed to New York City to defend his US Open title.[3] The couple's engagement became a news sensation, which took a toll on their relationship. When Perry turned down an offer of $50,000 to turn pro, he reportedly said it was because he would face tax issues and jeopardise his relationship with Lawson.[17] In April 1935, while Perry was in the United States, the engagement was called off.[3] Lawson reportedly stated that she broke off the engagement because publicity killed their romance, she had tired of the ridiculous rumours that had circulated in the media and she was opposed to Perry's plans to live permanently in America.[18]

Lawson met her future husband Francis William Lionel Collings Beaumont while filming the 1936 film Toilers of the Sea, a film adaption of Victor Hugo's 1866 novel Les Travailleurs de la mer.[19] Hugo's book is set in the British Crown Dependency Guernsey in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy, which includes the island of Sark, a feudal territory ruled by the Seigneur of Sark. Beaumont's mother, Dame Sibyl Mary Collings Beaumont Hathaway, who was the ruling 21st Seigneur of Sark, wrote in her autobiography that the scenes from the film were shot on Sark and that her son provided backing for the film, along with French director/producer Jean Choux;[20][21] in the film credits the production company L. C. Beaumont is mentioned, but not Choux.[20][22] At this time Beaumont was married and had a son, the future 22nd Seigneur of Sark. It is uncertain when the affair between Lawson and Beaumont began, but Beaumont's wife purchased an announcement in the edition of 30 November 1937 of The Times asking for a "dissolution" of their marriage "on the ground of his adultery with Miss Mary Lawson."[23] That year the Beaumonts were divorced,[24] and on 22 June 1938 Beumont and Lawson were married in Chelsea.[25] In her memoirs, Hathaway makes no mention of her son's second wife, rather she praises his first wife as a "charming girl"[26] and states that "on account of behaviour of my sons … there have been many heartbreaking blows."[27] Upon marriage Lawson legally changed her name to Mary Elizabeth Beaumont, but she continued to use Mary Lawson as her stage name.[1]

Death

When the Second World War broke out Sark was occupied by the German military and Beaumont joined the Royal Air Force, reaching the rank of flight lieutenant.[3] In May 1941 Flt Lt Beaumont received a week's leave and he, Lawson, friends and family travelled to Liverpool,[3] where according to Hathaway they stayed at a hotel at 126 Smithdown Road in the Sefton Park district. This, however, is unlikely as 126 Smithdown Road was the address for Smithdown Road Infirmary (later Sefton General Hospital) and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission information suggests they were staying at 74 Bedford Street in Toxteth.[1][28][29] On 1 May the German Luftwaffe began a bombing campaign on Liverpool that lasted for more than a week. On 4 May as the warning sirens went off, family and friends at the home, including Lawson's sister Dorothy, took safety in a shelter, while Lawson and Beaumont stayed in their room.[3] The home was destroyed, killing the couple, while all those who sought safety in the shelter survived.[3] Lawson's death was announced in newspapers around the globe, but was overshadowed by the greater destruction of the war.[2][30] Both Lawson and her husband are buried in Kirkdale Cemetery, Liverpool.[29][31]

Filmography

- 1934 – Youthful Folly[13]

- 1934 – Colonel Blood[13]

- 1935 – D'Ye Ken John Peel?[13] (US title: Captain Moonlight)

- 1935 – Can You Hear Me, Mother?[13]

- 1935 – Scrooge 'Scrooge Wife'[13]

- 1935 – Radio Pirates, aka Big Ben Calling[13]

- 1935 – Falling in Love[13] (US title: Trouble Ahead)

- 1935 – A Fire Has Been Arranged[13]

- 1935 – Things Are Looking Up[13]

- 1936 – House Broken[13]

- 1936 – To Catch a Thief[13]

- 1936 – Toilers of the Sea[13]

- 1937 – Cotton Queen, aka Crying Out Loud[13]

- 1938 – Oh Boy![13]

Stage performances

- 1928 – Good News at the Carlton Theatre in London[4]

- 1929–1930 – Hold Everything! at the Theatre Royal in Sydney[6]

- 1930 – The Desert Song in Sydney[5]

- 1931 – White Horse Inn at the Coliseum Theatre in London[2]

- 1932 – Casanova at the Coliseum Theatre in London[32]

- 1935 – Life Begins at Oxford Circus at the London Palladium in Lond[33]

- 1937 – Home and Beauty at the Adelphi Theatre in London[34]

- 1937–1938 – Going Greek at the Gaiety Theatre in London[35]

- 1938–1939 – Running Riot at the Gaiety Theatre in London[36]

- 1939–1940- The Two Bouquets at the Embassy Theatre in London[37]

- 1940 – White Horse Inn at the Coliseum Theatre in London.[15]

References

- "Mary Elizabeth Beaumont (otherwise Mary Lawson), deceased". The London Gazette. No. 35208. 4 July 1941. p. 3854.

- "Second Raid on Humber Area Many Casualties, Other Attacks in North Midlands". The Times (48922). London. 10 May 1941. col C, p. 2.

- Lloyd, Chris (19 March 2003). "Echo memories – Tragic star whose light was snuffed out too early". The Northern Echo. p. 6b.

- ""Good News." American Musical Comedy at the Carlton". The Times (44973). London. 16 August 1928. col C, p. 8.

- "Around the Theatres". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 January 1934. p. 9 of The Women's Supplement. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Theatre Royal". Argus. No. 26,005. 17 December 1929. p. 22. Retrieved 3 June 2009.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Colonel Blood at IMDb

- Scrooge at IMDb

- D'Ye Ken John Peel? at IMDb

- Cotton Queen at IMDb

- Things Are Looking Up at IMDb

- A Fire Has Been Arranged at IMDb

- Mary Lawson at IMDb

- "Shows for the Troops A Rapid Expansion". The Times (48459). London. 10 November 1939. col F, p. 6.

- "Reviews". Reviews. The Times (48571). London. 23 March 1940. col D, p. 4.

- Low, Rachael. The History of British Film, Volume VII: The History of the British Film 1929–1939: Film Making in 1930s Britain. 2005: Routledge. p. 358. 0415156521.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Perry's Refusal". The Canberra Times. vol. 8, issue 2174. 31 August 1934. p. 2. Retrieved 2 June 2009.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Another Romance Endedl". The Age. no. 24, 963. 17 April 1935. p. 12. Retrieved 2 June 2009.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Toilers of the Sea at IMDb

- Jean Choux at IMDb

- Hathaway incorrectly writes that the film was shot in 1938. Hathaway, Sibyl (1962). Dame of Sark: An Autobiography. New York City: Coward-McCann, Inc. pp. 104–5.

- L.C. Beaumont at IMDb

- "Probate, Divorce, And Admiralty Division Decree Nisi Against Film Producer, Beaumont, E. C. v. Beaumont, F. W. L. C.". The Times (47855). London. 30 November 1937. col E, p. 4.

- Catalogue description for Document No. J 77/3752/4301. Divorce Court File: 4301. Appellant: Enid Corinne Beaumont. Respondent: Francis William Lionel C Beaumont. Type: Wife's petition for divorce [wd] 1937. The National Archives, Kew

- "News in Brief". The Times (48028). London. 23 June 1938. col C, p. 14.

- Hathaway, Sibyl (1962). Dame of Sark: An Autobiography. New York City: Coward-McCann, Inc. p. 70.

- Hathaway, Sibyl (1962). Dame of Sark: An Autobiography. New York City: Coward-McCann, Inc. p. 68.

- Hathaway, Sibyl (1962). Dame of Sark: An Autobiography. New York City: Coward-McCann, Inc. p. 130.

- "Casualty Details: Mary Elizabeth Beaumont". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Mary Lawson, British Actress, Killed in Raid". Chicago Tribune. 10 May 1941. p. 8.

- "Casualty Details: Francis William Lionel C. Beaumont". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "The Theatres "Casanova"". The Times (46140). London. 23 May 1932. col C, p. 12.

- "Varieties, & c.". The Times (47003). London. 4 March 1935. col C, p. 12.

- "Manchester Opera House "Coronation Revue" From our own correspondent". The Times (47567). London. 28 December 1936. col G, p. 15.

- "Concerts & c.". The Times (47939). London. 10 March 1938. col E, p. 12.

- "Concerts & c.". The Times (48238). London. 24 February 1939. col E, p. 14.

- "Opera And Ballet". The Times (48493). London. 20 December 1939. col F, p. 6.

External links

- Mary Lawson at IMDb

- photo of Mary Lawson at Durham County Council