Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is an idea in psychology proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper "A theory of Human Motivation" in Psychological Review.[2] There is little scientific basis to the idea: Maslow himself noted this criticism. Maslow subsequently extended the idea to include his observations of humans' innate curiosity. His theories parallel many other theories of human developmental psychology, some of which focus on describing the stages of growth in humans. He then created a classification system which reflected the universal needs of society as its base and then proceeding to more acquired emotions.[3]

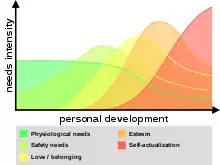

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is used to study how humans intrinsically partake in behavioral motivation. Maslow used the terms "physiological", "safety", "belonging and love", "social needs" or "esteem", and "self-actualization" to describe the pattern through which human motivations generally move. This means that in order for motivation to arise at the next stage, each stage must be satisfied within the individual themselves. Additionally, this hierarchy is a main base in knowing how effort and motivation are correlated when discussing human behavior. Each of these individual levels contains a certain amount of internal sensation that must be met in order for an individual to complete their hierarchy.[3] The goal in Maslow's hierarchy is to attain the fifth level or stage: self-actualization.[4]

Maslow's idea was fully expressed in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality.[5] The hierarchy remains a very popular framework in sociology research, management training[6] and secondary and higher psychology instruction. Maslow's classification hierarchy has been revised over time. The original hierarchy states that a lower level must be completely satisfied and fulfilled before moving onto a higher pursuit. However, today scholars prefer to think of these levels as continuously overlapping each other. This means that the lower levels may take precedence back over the other levels at any point in time.[3]

Maslow's idea emerged and was informed by his work with Blackfeet Nation through conversations with elders and inspiration from the shape and meaning of the Blackfoot tipi. However, Maslow's idea has been criticized for misrepresenting the Blackfoot worldview, which instead places self-actualization as a basis for community-actualization and community-actualization as a basis for cultural perpetuity, the latter of which exists at the top of the tipi in Blackfoot philosophy.[7][8]

Hierarchy

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid with the largest, most fundamental needs at the bottom and the need for self-actualization and transcendence at the top. In other words, the idea is that individuals' most basic needs must be met before they become motivated to achieve higher-level needs.[1][9] However, it has been pointed out that, although the ideas behind the hierarchy are Maslow's, the pyramid itself does not exist anywhere in Maslow's original work.[10]

The most fundamental four layers of the pyramid contain what Maslow called "deficiency needs" or "d-needs": esteem, friendship and love, security, and physical needs. If these "deficiency needs" are not met – except for the most fundamental (physiological) need – there may not be a physical indication, but the individual will feel anxious and tense. Maslow's idea suggests that the most basic level of needs must be met before the individual will strongly desire (or focus motivation upon) the secondary or higher-level needs. Maslow also coined the term "metamotivation" to describe the motivation of people who go beyond the scope of the basic needs and strive for constant betterment.[11]

The human brain is a complex system and has parallel processes running at the same time, thus many different motivations from various levels of Maslow's hierarchy can occur at the same time. Maslow spoke clearly about these levels and their satisfaction in terms such as "relative", "general", and "primarily". Instead of stating that the individual focuses on a certain need at any given time, Maslow stated that a certain need "dominates" the human organism.[5] Thus Maslow acknowledged the likelihood that the different levels of motivation could occur at any time in the human mind, but he focused on identifying the basic types of motivation and the order in which they would tend to be met.[12]

Basic needs

The basic need is a concept that was derived to explain and cultivate the foundation for motivation. This concept is the main physical requirement for human survival. This means that basic needs are universal human needs. Basic needs, being primal, are by default, a governor on the attainment of the "higher" needs. Efforts to accomplish higher needs may be interrupted temporarily by a deficit of primal needs, such as a lack of food or air. Basic needs are considered in internal motivation according to Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Maslow's idea is that humans are compelled to fulfill these basic needs first to pursue intrinsic satisfaction on a higher level.[3] If these needs are not achieved, it leads to an increase in displeasure within an individual. In return, when individuals feel this increase in displeasure, the motivation to decrease these discrepancies increases.[3] Basic needs can be defined as both traits and a state.[3] Basic needs as traits allude to long-term, unchanging demands that are required of basic human life. Physiological needs as a state allude to the unpleasant decrease in pleasure and the increase for an incentive to fulfill a necessity.[3] To pursue intrinsic motivation higher up Maslow's hierarchy, basic needs must be met first. This means that if a human is struggling to meet their basic needs, then they are unlikely to intrinsically pursue safety, belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization.

Physiological needs include:

Safety needs

Once a person's physiological needs are relatively satisfied, their safety needs take precedence and dominate behavior. In the absence of physical safety – due to war, natural disaster, family violence, childhood abuse, etc. and/or in the absence of economic safety – (due to an economic crisis and lack of work opportunities) these safety needs manifest themselves in ways such as a preference for job security, grievance procedures for protecting the individual from unilateral authority, savings accounts, insurance policies, disability accommodations, etc. This level is more likely to predominate in children as they generally have a greater need to feel safe. It includes shelter, job security, health, and safe environments. If a person does not feel safe in an environment, they will seek safety before attempting to meet any higher level of survival.

Safety needs include:

Social belonging

After physiological and safety needs are fulfilled, the third level of human needs is interpersonal and involves feelings of belongingness. According to Maslow, humans possess an effective need for a sense of belonging and acceptance among social groups, regardless of whether these groups are large or small. For example, some large social groups may include clubs, co-workers, religious groups, professional organizations, sports teams, gangs, and online communities. Some examples of small social connections include family members, intimate partners, mentors, colleagues, and confidants. Humans need to love and be loved – both sexually and non-sexually – by others.[2] Many people become susceptible to loneliness, social anxiety, and clinical depression in the absence of this love or belonging element. This need is especially strong in childhood and it can override the need for safety as witnessed in children who cling to abusive parents. Deficiencies due to hospitalism, neglect, shunning, ostracism, etc. can adversely affect the individual's ability to form and maintain emotionally significant relationships in general.

Social belonging needs include:

This need for belonging may overcome the physiological and security needs, depending on the strength of the peer pressure. In contrast, for some individuals, the need for self-esteem is more important than the need for belonging; and for others, the need for creative fulfillment may supersede even the most basic needs.[14]

Self-esteem

Esteem needs are ego needs or status needs. People develop a concern with getting recognition, status, importance, and respect from others. Most humans need to feel respected; this includes the need to have self-esteem and self-respect. Esteem presents the typical human desire to be accepted and valued by others. People often engage in a profession or hobby to gain recognition. These activities give the person a sense of contribution or value. Low self-esteem or an inferiority complex may result from imbalances during this level in the hierarchy. People with low self-esteem often need respect from others; they may feel the need to seek fame or glory. However, fame or glory will not help the person to build their self-esteem until they accept who they are internally. Psychological imbalances such as depression can distract the person from obtaining a higher level of self-esteem.

Most people have a need for stable self-respect and self-esteem. Maslow noted two versions of esteem needs: a "lower" version and a "higher" version. The "lower" version of esteem is the need for respect from others and may include a need for status, recognition, fame, prestige, and attention. The "higher" version manifests itself as the need for self-respect, and can include a need for strength, competence,[3] mastery, self-confidence, independence, and freedom. This "higher" version takes guidelines, the "hierarchies are interrelated rather than sharply separated".[5] This means that esteem and the subsequent levels are not strictly separated; instead, the levels are closely related.

Self-actualization

"What a man can be, he must be."[5]:91 This quotation forms the basis of the perceived need for self-actualization. This level of need refers to the realization of one's full potential. Maslow describes this as the desire to accomplish everything that one can, to become the most that one can be.[5]:92 People may have a strong, particular desire to become an ideal parent, succeed athletically, or create paintings, pictures, or inventions.[5]:93 To understand this level of need, a person must not only succeed in the previous needs but master them. Self-actualization can be described as a value-based system when discussing its role in motivation. Self-actualization is understood as the goal or explicit motive, and the previous stages in Maslow's Hierarchy fall in line to become the step-by-step process by which self-actualization is achievable; an explicit motive is the objective of a reward-based system that is used to intrinsically drive completion of certain values or goals.[3] Individuals who are motivated to pursue this goal seek and understand how their needs, relationships, and sense of self are expressed through their behavior. Self-actualization can include:[3]

- Partner Acquisition

- Parenting

- Utilizing & Developing Talents & Abilities

- Pursuing goals

Transcendence

In his later years, Abraham Maslow explored a further dimension of motivation, while criticizing his original vision of self-actualization.[15][16][17][18] By these later ideas, one finds the fullest realization in giving oneself to something beyond oneself—for example, in altruism or spirituality. He equated this with the desire to reach the infinite.[19] "Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos".[20]

Criticism

Although recent research appears to validate the existence of universal human needs, the hierarchy proposed by Maslow is called into question.[21][22]

Unlike most scientific theories, Maslow's hierarchy of needs has widespread influence outside academia. As Uriel Abulof argues, "The continued resonance of Maslow's theory in popular imagination, however unscientific it may seem, is possibly the single most telling evidence of its significance: it explains human nature as something that most humans immediately recognize in themselves and others."[23] Still, academically, Maslow's idea is heavily contested.

Methodology

Maslow studied what he called the master race of people such as Albert Einstein, Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frederick Douglass rather than mentally ill or neurotic people, writing that "the study of crippled, stunted, immature, and unhealthy specimens can yield only a cripple psychology and a cripple philosophy."[5]:236 Maslow studied the healthiest 1% of the college student population.[24]

Global ranking

In their extensive review of research based on Maslow's hierarchy, Wahba and Bridwell found little evidence for the ranking of needs that Maslow described or for the existence of a definite hierarchy at all.[25]

The order in which the hierarchy is arranged has been criticized as being ethnocentric by Geert Hofstede.[26] In turn, Hofstede's work has been criticized by others.[27] Maslow's hierarchy of needs fails to illustrate and expand upon the difference between the social and intellectual needs of those raised in individualistic societies and those raised in collectivist societies. The needs and drives of those in individualistic societies tend to be more self-centered than those in collectivist societies, focusing on improvement of the self, with self-actualization being the apex of self-improvement. In collectivist societies, the needs of acceptance and community will outweigh the needs for freedom and individuality.[28]

Ranking of sex

The position and value of sex on the pyramid has also been a source of criticism regarding Maslow's hierarchy. Maslow's hierarchy places sex in the needs category along with food and breathing; it lists sex solely from an individualistic perspective. For example, sex is placed with other physiological needs which must be satisfied before a person considers "higher" levels of motivation. Some critics feel this placement of sex neglects the emotional, familial, and evolutionary implications of sex within the community, although others point out that this is true of all of the basic needs.[29][30]

Changes to the hierarchy by circumstance

The higher-order (self-esteem and self-actualization) and lower-order (physiological, safety, and love) needs classification of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is not universal and may vary across cultures due to individual differences and availability of resources in the region or geopolitical entity/country.

In one study,[31] exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of a thirteen-item scale showed there were two particularly important levels of needs in the US during the peacetime of 1993 to 1994: survival (physiological and safety) and psychological (love, self-esteem, and self-actualization). In 1991, a retrospective peacetime measure was established and collected during the Persian Gulf War and US citizens were asked to recall the importance of needs from the previous year. Once again, only two levels of needs were identified; therefore, people have the ability and competence to recall and estimate the importance of needs. For citizens in the Middle East (Egypt and Saudi Arabia), three levels of needs regarding importance and satisfaction surfaced during the 1990 retrospective peacetime. These three levels were completely different from those of the US citizens.

Changes regarding the importance and satisfaction of needs from the retrospective peacetime to the wartime due to stress varied significantly across cultures (the US vs. the Middle East). For the US citizens, there was only one level of needs since all needs were considered equally important. With regards to satisfaction of needs during the war, in the US there were three levels: physiological needs, safety needs, and psychological needs (social, self-esteem, and self-actualization). During the war, the satisfaction of physiological needs and safety needs were separated into two independent needs while during peacetime, they were combined as one. For the people of the Middle East, the satisfaction of needs changed from three levels to two during wartime.[32][33]

A 1981 study looked at how Maslow's hierarchy might vary across age groups.[34] A survey asked participants of varying ages to rate a set number of statements from most important to least important. The researchers found that children had higher physical need scores than the other groups, the love need emerged from childhood to young adulthood, the esteem need was highest among the adolescent group, young adults had the highest self-actualization level, and old age had the highest level of security, it was needed across all levels comparably. The authors argued that this suggested Maslow's hierarchy may be limited as a theory for developmental sequence since the sequence of the love need and the self-esteem need should be reversed according to age.

Self-actualization

The term "self-actualization" may not universally convey Maslow's observations; this motivation refers to focusing on becoming the best person that one can possibly strive for in the service of both the self and others.[5] Maslow's term of self-actualization might not properly portray the full extent of this level; quite often, when a person is at the level of self-actualization, much of what they accomplish in general may benefit others, or "the greater good".

Human or non-human needs

Abulof argues that while Maslow stresses that "motivation theory must be anthropocentric rather than animalcentric," he posits a largely animalistic hierarchy, crowned with a human edge: "Man's higher nature rests upon man's lower nature, needing it as a foundation and collapsing without this foundation… Our godlike qualities rest upon and need our animal qualities." Abulof notes that "all animals seek survival and safety, and many animals, especially mammals, also invest efforts to belong and gain esteem... The first four of Maslow's classical five rungs feature nothing exceptionally human."[35] Even when it comes to "self-actualization", Abulof argues, it is unclear how distinctively human is the actualizing "self". After all, the latter, according to Maslow, constitutes "an inner, more biological, more instinctoid core of human nature," thus "the search for one's own intrinsic, authentic values" checks the human freedom of choice: "A musician must make music," so freedom is limited to merely the choice of instrument.[35]

See also

- ERG theory, which further expands and explains Maslow's theory

- First World problem reflects on trivial concerns in the context of more pressing needs.

- Manfred Max-Neef's Fundamental human needs, Manfred Max-Neef's model

- Functional prerequisites

- Human givens, a theory in psychotherapy that offers descriptions on the nature, needs, and innate attributes of humans

- Need theory, David McClelland's model

- Positive disintegration

- Self-determination theory, Edward L. Deci's and Richard Ryan's model

References

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- Maslow, A.H. (1943). "A theory of human motivation". Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.7586. doi:10.1037/h0054346 – via psychclassics.yorku.ca.

- Deckers, Lambert (2018). Motivation: Biological, Psychological, and Environmental. Routledge Press.

- M., Wills, Evelyn (2014). Theoretical basis for nursing. ISBN 9781451190311. OCLC 857664345.

- Maslow, A (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-041987-5.

- Kremer, William Kremer; Hammond, Claudia (31 August 2013). "Abraham Maslow and the pyramid that beguiled business". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Grayshield, Lisa; Begay, Marilyn; L. Luna, Laura (2020). "IWOK Epistemology in Counseling Praxis". Indigenous Ways of Knowing in Counseling: Theory, Research, and Practice. Springer International Publishing. pp. 7–23. ISBN 9783030331788.

- Kingston, John (2020). "Maslow and Transcendence". American Awakening: Eight Principles to Restore the Soul of America. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310360759.

- Steere, B. F. (1988). Becoming an effective classroom manager: A resource for teachers. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-620-7.

- Eaton, Sarah Elaine (August 4, 2012). "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Is the Pyramid a Hoax?". Learning, Teaching, and Leadership.

- Goble, F. (1970). The third force: The psychology of Abraham Maslow. Richmond, CA: Maurice Bassett Publishing. pp. 62.

- "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs in Education". Education Library. 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs". simply psychology. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Cherry, Kendra. "What Is Self-Actualization?". About.com. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- Maslow, Abraham H. (1996). "Critique of self-actualization theory". In E. Hoffman (ed.). Future visions: The unpublished papers of Abraham Maslow. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 26–32.

- Maslow, Abraham H. (1969). "The farther reaches of human nature". Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 1 (1): 1–9.

- Maslow, Abraham H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: The Viking Press.

- Koltko-Rivera, Mark E. (2006). "Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification" (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 10 (4): 302–317. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.10.4.302. S2CID 16046903.

- Garcia-Romeu, Albert (2010). "Self-transcendence as a measurable transpersonal construct" (PDF). Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 421: 26–47.

- Maslow 1971, p. 269.

- Villarica, H. (August 17, 2011). "Maslow 2.0: A new and improved recipe for happiness". The Atlantic.

- Tay, L.; Diener, E. (2011). "Needs and subjective well-being around the world". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 101 (2): 354–365. doi:10.1037/a0023779. PMID 21688922.

- Abulof, Uriel (2017-12-01). "Introduction: Why We Need Maslow in the Twenty-First Century". Society. 54 (6): 508–509. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0198-6. ISSN 0147-2011.

- Mittelman, W. (1991). "Maslow's study of self-actualization: A reinterpretation". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 31 (1): 114–135. doi:10.1177/0022167891311010. S2CID 144849415.

- Wahba, M. A.; Bridwell, L. G. (1976). "Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory". Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 15 (2): 212–240. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6.

- Hofstede, G. (1984). "The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept" (PDF). Academy of Management Review. 9 (3): 389–398. doi:10.5465/amr.1984.4279653. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-12.

- Jones, M. (28 June 2007). "Hofstede - Culturally questionable?". Faculty of Commerce - Papers (Archive).

- Cianci, R.; Gambrel, P. A. (2003). "Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture". Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship. 8 (2): 143–161.

- Kenrick, D. (May 19, 2010). "Rebuilding Maslow's pyramid on an evolutionary foundation". Psychology Today.

- Kenrick, D. T.; Griskevicius, V.; Neuberg, S. L.; Schaller, M. (2010). "Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 5 (3): 292–314. doi:10.1177/1745691610369469. PMC 3161123. PMID 21874133.

- Tang, T. L.; West, W. B. (1997). "The importance of human needs during peacetime, retrospective peacetime, and the Persian Gulf War". International Journal of Stress Management. 4 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1007/BF02766072 (inactive 2021-01-15).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Tang, T. L.; Ibrahim, A. H. (1998). "Importance of human needs during retrospective peacetime and the Persian Gulf War: Mid-eastern employees". International Journal of Stress Management. 5 (1): 25–37. doi:10.1023/A:1022902803386. S2CID 141983215.

- Tang, T. L.; Ibrahim, A. H.; West, W. B. (2002). "Effects of war-related stress on the satisfaction of human needs: The United States and the Middle East". International Journal of Management Theory and Practices. 3 (1): 35–53.

- Goebel, B. L.; Brown, D. R. (1981). "Age differences in motivation related to Maslow's need hierarchy". Developmental Psychology. 17 (6): 809–815. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.17.6.809.

- Abulof, Uriel (Dec 2017). "Be Yourself! How Am I Not Myself?". Society. 54 (6): 530–532. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0183-0. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 148897359.

Further reading

- Heylighen, Francis (1992). "A cognitive-systemic reconstruction of Maslow's theory of self-actualization" (PDF). Behavioral Science. 37 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1002/bs.3830370105.

- Koltko-Rivera, Mark E. (2006). "Rediscovering the later version of Maslow's hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification". Review of General Psychology 10.4: 302.

- Kress, Oliver (1993). "A new approach to cognitive development: ontogenesis and the process of initiation". Evolution and Cognition. 2 (4): 319–332.

- Maslow, Abraham H. (1993). "Theory Z". In Abraham H. Maslow, The farther reaches of human nature (pp. 270–286). New York: Arkana (first published Viking, 1971). Reprinted from Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1969, 1(2), 31–47.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maslow's hierarchy of needs. |

- "A Theory of Human Motivation", original 1943 article by Maslow.