Maternal healthcare in Texas

Maternal healthcare in Texas refers to the provision of family planning services, abortion options, pregnancy-related services, and physical and mental well-being care for women during the prenatal and postpartum periods. The provision of maternal health services in each state can prevent and reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality and fetal death.[1][2]

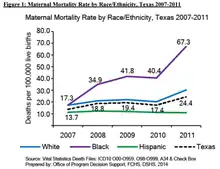

The maternal healthcare system in Texas has undergone legislative changes in funding and the provision of family planning and abortion services, in relation to other states in the United States. The system in Texas has also received attention in regards to the state's maternal mortality ratio, currently the highest in the United States.[3] Maternal deaths have steadily increased in Texas from 2010, with more than 30 deaths occurring for every 100,000 live births in 2014.[4] The diverse demography of Texas has been identified as one factor contributing to this mortality rate, with mortality being higher among ethnic minorities such as African-American and Hispanic women.[5] In 2013, Texas legislation established the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force to begin investigating the causes of the maternal mortality rates in the state as well as suggesting ways in which it could be reduced or averted.

Family Planning Services

In the late 1900s, the importance of family planning services captured the attention of healthcare professionals and policy makers. The recognition that unintentional pregnancies had adverse health outcomes for mothers and increased costs of maternal and infant care coupled with ethical considerations led to the passage of Title X in 1970 and the creation of federal- and state-funded family planning programs.[6][7][8] Under Title X funding in Texas, family planning organizations participate in the 340B drug-pricing program, which reduces contraception costs by 50–80%. Under Title X regulations, clinics are also allowed to provide confidential family planning services to adolescents.[9]

Contraception and Screening

In 2007, the Health and Human Services Commission of Texas established the Women's Health Program (WHP), a Medicaid waiver program that received 90% of its funding from the federal level.[9][10] The Program provided family planning services for women from the ages of 18–44 whose incomes were 185% below the federal poverty level.[9]

In September 2011, the program served ~119,000 low-income women.[9] In December 2011, the state of Texas established legislation that excluded family planning providers affiliated with abortion services, such as Planned Parenthood clinics, from the WHP.[9][10] As a result, the federal government ruled this as a violation of federal law, and in March 2012, discontinued federal funding for the WHP. The WHP was then replaced with a program that was 100% funded by revenue from the state of Texas.[6][9][10]

The exclusion of Planned Parenthood clinics from the WHP was found to be associated with a reduced use of contraception by clients.[10] After the exclusion of Planned Parenthood clinics from the WHP, the claims in Planned Parenthood clinics for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) reduced by 35.5% and the claims for injectable contraceptives reduced by 31.1%.[10] After the exclusion, there was also found to be an increase in childbirth covered under Medicaid from 7.0% to 8.4% in the counties with Planned Parenthood affiliates.[10]

In addition to the Women's Health Program, from September 2010 to August 2011, the Texas Department of State Health Services allocated $49.3 million in funding to private, public, and Planned Parenthood affiliated clinics through Title X, V, and XX funding to provide family planning services.[9]

In September 2011, preceding the exclusion of programs from WHP, the state of Texas reduced its family planning funding from $111.0 million to $37.9 million through the removal of Title V and Title XX block grants.[9] The funds were re-allocated away from family planning providers to other state and federal programs. With the remaining funding, family planning programs were organized into a 3-tiered system, with public agencies and federally funded health centers (tier 1) being prioritized over agencies that provided family planning services as a part of primary care (tier 2) and those that specialized in the provision of family planning services (tier 3).[6][9][10]

The reduction of the budget for family planning services and the creation of three-tiered program was associated with the closing of 82 family-planning clinics, with one third of the clinics being Planned Parenthood affiliates.[10] Without subsidized aid, fewer clinics were able to afford contraception, and as a result, reduced access to IUDs and implants for patients.[9] Clinics also began to reduce their service hours. With the loss of funding, clinics lost their participation in the 340B drug-pricing program, which had reduced contraception costs from 50 – 80%.[9] Clinics also lost their exemption status from a Texas law requiring parental consent for provision of family planning services to adolescents. Family planning organizations reported a 41–92% reduction in clients after the reduction and reallocation of family planning funding.[9]

The changes in family planning funding and exclusion of Planned Parenthood clinics from the WHP did not seem to affect screening and counseling services. Services such as cervical cancer screening, chlamydia and gonorrhea screening, and HIV testing continue to be offered at private and public clinics.[9]

Prenatal and Postpartum Care

Prenatal care is a form of preventative health care that aims to reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality and fetal defects and death.[1][2] Women's access to prenatal care services is dependent on and can be limited by their socioeconomic status or region of residency.[1] One study conducted in 2010 through interviews of low-income women living in San Antonio, Texas, showed how those with limited education or in singly inhabited houses initiated prenatal care services later in their pregnancies.[11] The women reported "service-related" barriers as the number one reason for not initiating prenatal care services.[11]

Postpartum care is the provision of healthcare services upon delivery and mirrors prenatal care services. Postpartum care is offered both for the physical and mental repercussions that may result after delivery. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System is one way of gauging the mental health of women after delivery, and is used by hospitals in the state of Texas.[12] In 2003, Texas passed the Postpartum Depression to Pregnant Women Act, requiring healthcare professionals to equip women with information on accessing organizations that provide counseling and postpartum guidance.[13] This act also urged the consideration of insurance coverage and other economic factors in providing women with postpartum care.

Regarding one area of postpartum care, a study conducted in 2014 surveyed women living in Austin and El Paso, Texas on their preferred method of contraception six months after delivery and compared it with their current contraception use.[14] The surveys found that while women preferred to use LARC methods of contraception, they were unable to use or access them at the time.[14] Postpartum contraception has been deemed an integral part of the maternal healthcare system, especially because 61% of all unwanted pregnancies occur for women who have undergone delivery at least once.[15][16]

Maternal Mortality

According to the World Health Organization, maternal mortality is defined as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy."[17] The maternal mortality rates in Texas have been a source of concern as well as much discussion. From 2000 to 2010, the maternal mortality rate in Texas increased from 17.7 (for every 100,000 live births) to 18.6.[3] It must be noted that during this period, in 2006, Texas included the consideration of pregnancy on its death certificate.[3] However, this was not seen to visibly affect the maternal mortality rates in the ten-year time period. After 2010, the maternal mortality rate doubled, exceeding 35 between 2010 and 2014 and remaining higher than 30 in 2014.[3]

In the US, from 1987 to 2009, the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths included hemorrhage, sepsis, and hyperintensive disorders.[18] From 2006 to 2009, these causes changed, with cardiovascular conditions accounting for more than a third of pregnancy-related deaths.[18]

While research is ongoing on the causes of maternal mortality in Texas, maternal mortality in the US has been linked to chronic health conditions in women.[19][20] Cardiovascular conditions were shown to account for at least one third of pregnancy-related deaths. Behavioral factors, such as smoking, overdoses, and suicide have also shown to be present in a high frequency during the period of pregnancy and postpartum period.[19][21] Similarly, depression and anxiety have been prevalent in women during the postpartum period.[22] In Texas, African-American women are at the highest risk of maternal death.[19]

In 2013, the Senate Bill 495 passed, leading to the establishment of the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force to assess the factors contributing to maternal death in the state and suggest measures to reducing its incidence.[23][24] In the 2016 Biennial Report, the Task Force identified cardiac event, drug overdose, hypertension, hemorrhage, and sepsis as being the top five factors contributing to maternal death in Texas.[23] Since opioids are the most common method of drug abuse in Texas, the Task Force has initiated the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Prevention Pilot to reduce the incidence of this syndrome in newborns resulting from maternal opioid use.[23][25] The Task Force is also working toward extending the number of days after delivery to which a woman in the Healthy Texas Women program can access health services.[24]

Other initiatives the Task Force has worked on include The Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies, which enables the delivery of postpartum health services to women while raising awareness of maternal and infant mortality.[24] Other programs such as Someday Starts Now and Preconception Peer Education, work to raise community awareness of maternal morbidity and mortality, and are specifically targeted to minority populations of childbearing age.[24] The Task Force is planning to allocate Title V funding to these programs and thus strengthen community health and awareness of maternal mortality and morbidity.[23]

References

- Alexander, Greg (2001). "Assessing the Role and Effectiveness of Prenatal Care: History, Challenges, and Direction for Future Research". Public Health Reports. 116 (4): 306–316. doi:10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50052-3. PMC 1497343. PMID 12037259.

- Langer, Ana (2002). "Are women and providers satisfied with antenatal care?". BMC Women's Health. 2: 7. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-2-7. PMC 122068. PMID 12133195.

- MacDorman, Marian F.; Declercq, Eugene; Cabral, Howard; Morton, Christine (2016). "Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 128 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001556. PMC 5001799. PMID 27500333.

- MacDorman, Marian F.; Declercq, Eugene; Cabral, Howard; Morton, Christine (2016). "Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 128 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001556. PMC 5001799. PMID 27500333.

- Colman, Silvie (2011). "Regulating abortion: impact on patients and providers in Texas" (PDF). Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 30 (4): 775–797. doi:10.1002/pam.20603.

- White, Kari (2012). "Cutting Family Planning in Texas". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (13): 1179–1181. doi:10.1056/nejmp1207920. PMC 4418511. PMID 23013071.

- Mohllajee, A P.; Curtis, K M.; Morrow, B; Marchbanks, P A. (2007). "Pregnancy intention and its relationship to birth and maternal outcomes". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 109 (3): 678–686. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000255666.78427.c5. PMID 17329520.

- "The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature". Studies in Family Planning.

- White, Kari; Hopkins, Kristine; Aiken, Abigail R. A.; Stevenson, Amanda; Hubert, Celia; Grossman, Daniel; Potter, Joseph E. (2015). "The impact of reproductive health legislation on family planning clinic services in Texas". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (5): 851–858. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302515. PMC 4386528. PMID 25790404.

- Stevenson, Amanda J. (2016). "Effect of removal of planned parenthood from the Texas Women's Health Program". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (9): 853–860. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1511902. PMC 5129844. PMID 26836435.

- Sunil, T.S. (2010). "Initiation of and barriers to prenatal care use among low-income women in San Antonio, Texas". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 14 (1): 133–40. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0419-0. PMID 18843529.

- Chalmers, B (2001). "WHO principles of perinatal care: The essential antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum care course". Birth. 28 (3): 202–7. doi:10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00202.x. PMID 11552969.

- Texas Department of Health Services (2003). "HB 341: The provision of information on postpartum depression to pregnant women". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Potter, J.E. (2010). "Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas". Contraception. 88: 437. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.031.

- Finer, LB (2014). "Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the united states, 2001–2008". American Journal of Public Health. 104 Suppl 1: S43-8. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301416. PMC 4011100. PMID 24354819.

- Finer, LB (2011). "Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006". Contraception. 84 (5): 478–485. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. PMC 3338192. PMID 22018121.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1992.

- "Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now?". Journal of Women's Health.

- Callaghan, WM (2012). "Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 120 (5): 1029–36. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. PMID 23090519.

- Creanga, AA (2014). "Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now?". Women's Health. 23 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1089/jwh.2013.4617. PMC 3880915. PMID 24383493.

- Farr, SL (2011). "Depression, diabetes, and chronic disease risk factors among U.S. women of reproductive age". Chronic Diseases. PMID 22005612.

- Ko, JY (2012). "Depression and treatment among U.S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009". Journal of Women's Health. 21 (8): 830–6. doi:10.1089/jwh.2011.3466. PMC 4416220. PMID 22691031.

- Texas State Department of Health Services (2016). "Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Texas State Department of Health Services (2014). "Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force Report". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wendell, AD (2013). "Overview and epidemiology of substance abuse in pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 56 (1): 91–96. doi:10.1097/grf.0b013e31827feeb9. PMID 23314721.