Metta Fock

Metta (or Mätta) Charlotta Fock, née Ridderbjelke (10 June 1765 - 7 November 1810), was a Swedish noble and sentenced murderer. She was executed for murdering her spouse, son and daughter in order to marry her lover.

Life

Metta Fock was the daughter of quartermaster noble Axel Erik Ridderbjelke and Helena Margareta Gripenmark. In 1783, she married the noble sergeant Henrik Johan Fock (1757-1802). The marriage was arranged. The couple had several children, four of whom, two daughters and two sons, were alive by 1800.

The couple lived on the estate Lilla Gisslaved in Trevattna parish in Västergötland. It was a small farm with only one tenant, and their economic standard was very low for members of the nobility. The mental capacity of Henrik Johan Fock was restricted. He was described as "very foolish, though not insane",[1] which was reportedly why he never advanced from the rank of sergeant: he was not able to manage the affairs of the farm, and Metta Fock therefore had her husband placed under the guardianship of her brother and took over the management herself.

Metta Fock was rumored in the parish to have a lover, the married sergeant and game keeper Johan Fägercrantz, who often visited Lilla Gisslaved and to whom she often sent letters. The messengers she sent to deliver the letters were always illiterate, but later claimed to have showed them to a major, who read them and later testified that they included love poems. Gossip also claimed that Johan Fägercrantz had abused Johan Fock physically during one of his visits.

Deaths

In June 1802, Metta Fock's eldest son, the thirteen-year-old Claes, her three-year-old deaf mute daughter Charlotta, and finally her spouse Henrik Johan, all died within a couple of days after having experienced violent vomiting, temporarily improvement, followed by a hasty death. After their death, Metta Fock left home and spent a couple of days with her eldest daughter's fiance and then at the Norwegian border, before she returned. This caused rumors that she had murdered her spouse and her children in order to marry her lover.

These events, coupled with the rumors of her love affair, resulted in a suggestion from the local länsman to have an autopsy performed on the remains of her spouse. This demand was denied because it was deemed unnecessary, and the funeral was conducted. However, the governor gave order that the autopsy was to be conducted anyway and that the corpse was to be exhumed. The doctor, however, only looked at the corpse in the coffin and decided that it was impossible to conduct the autopsy because of the decay. After this, baron Adam Fock of Höverö, the patriarch of the Fock family and her late spouse's cousin's nephew, had an autopsy performed by a doctor from Skara. He did so without asking for permission from the authorities, and offered the doctor a sizable sum if the result of the autopsy proved poisoning.

Trial

Metta Fock was arrested and accused of having murdered her spouse and two children with arsenic in order to marry her lover. She denied the charges. Fock was denied contact with the outside world during her arrest. She was repeatedly questioned, but denied contact with a defense lawyer. She called her own witnesses and tried to prove that there were maggots in the remains, which was known not to be present in the remains of the victims of arsenic poisoning, and that there had been measles present in the parish at the time of the deaths. In April 1804, Johan Fägercrantz admitted to having an affair with her, but denied any knowledge of any murder. Johan Fägercrantz was sentenced to 28 days on water and bread for fornication and adultery.

In April 1805, a majority of the members of the court judged her guilt "more than half proven". However, Fock refused to confess and maintained her own version of events. A law at the time allowed for an accused person who could not be judged guilty but was regarded as dangerous for society to be kept prisoner awaiting their confession. This law was used for Metta Fock. She protested to the monarch and was granted a reprieve and allowed to summon more witnesses to her defense; however, the prison sentence was confirmed in November 1805. In 1806, she was placed as a prisoner at Carlsten awaiting her confession. She was the only female prisoner ever to be kept at Carlsten, which normally only housed male prisoners. She was kept in an isolation cell, and tended only by two priests, who were to encourage her to confess the truth.

Imprisonment and execution

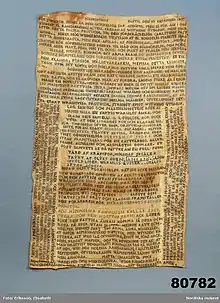

On 10 December 1805, during her time in prison, Metta Fock made a message of appeal by embroidery on 27 bits of linen cloth which she had sewn together, as she was not granted the right to pen and paper. In it, she stated her innocence and complained about the treatment she had received. The appeal came to be in the possession of Sophie Adlersparre, who donated it to Nordiska museet in her will, where it is still kept.

In April 1809, she confessed to her guilt. She later retracted her confession and started to defend herself again, but without success. She was sentenced to be executed by decapitation followed by burning; prior to this, her hand was to be cut off. The execution took place on 7 November 1810 at Fägredsmon in Västergötland.

Metta Fock in fiction

The case was described in the book Trefalt mord? ('Trice Murder?') by the lawyer Yngve Lyttkens (1996), who describes the investigation and trial as partial, the confession of Fock as doubtful, and Metta Fock as a potential victim of a miscarriage of justice.

A song is dedicated to her by Stefan Andersson in the album Skeppsråttan (2009).

She is the main subject of the novel Mercurium by Ann Rosman (2012), in which she is portrayed as innocent.

References

- Henrik Fock: Släkten Fock: personer och händelser under 450 år

- Lindberg, Gustaf (1921). Ett syskonpar: Johan Gustaf Ridderbjelke och Metta Charlotta Ridderbjelke (in Swedish). Tidaholm: Förf.

- Lyttkens, Yngve (1956). Trefalt mord?. Stockholm: Bonnier. Libris 541372

- Charlotta Ridderbjelke i Wilhelmina Stålberg, Anteckningar om svenska qvinnor (1864)

- Henrik Fock: Släkten Fock: personer och händelser under 450 år