Meyer–Schuster rearrangement

The Meyer–Schuster rearrangement is the chemical reaction described as an acid-catalyzed rearrangement of secondary and tertiary propargyl alcohols to α,β-unsaturated ketones if the alkyne group is internal and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes if the alkyne group is terminal.[1] Reviews have been published by Swaminathan and Narayan,[2] Vartanyan and Banbanyan,[3] and Engel and Dudley,[4] the last of which describes ways to promote the Meyer–Schuster rearrangement over other reactions available to propargyl alcohols.

When catalyzed by base, the reaction is called the Favorskii reaction.

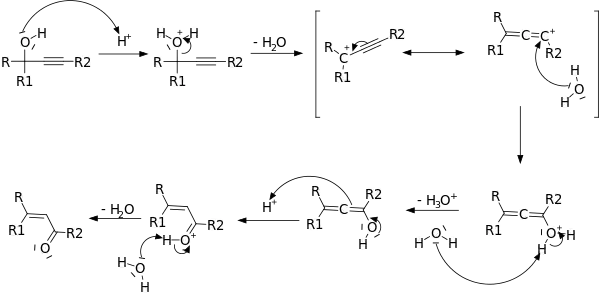

Mechanism

The reaction mechanism[5] begins with the protonation of the alcohol which leaves in an E1 reaction to form the allene from the alkyne. Attack of a water molecule on the carbocation and deprotonation is followed by tautomerization to give the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound.

Edens et al. have investigated the reaction mechanism.[6] They found it was characterized by three major steps: (1) the rapid protonation of oxygen, (2) the slow, rate-determining step comprising the 1,3-shift of the protonated hydroxy group, and (3) the keto-enol tautomerism followed by rapid deprotonation.

In a study of the rate-limiting step of the Meyer–Schuster reaction, Andres et al. showed that the driving force of the reaction is the irreversible formation of unsaturated carbonyl compounds through carbonium ions.[7] They also found the reaction to be assisted by the solvent. This was further investigated by Tapia et al. who showed solvent caging stabilizes the transition state.[8]

Rupe rearrangement

The reaction of tertiary alcohols containing an α-acetylenic group does not produce the expected aldehydes, but rather α,β-unsaturated methyl ketones via an enyne intermediate.[9][10] This alternate reaction is called the Rupe reaction, and competes with the Meyer–Schuster rearrangement in the case of tertiary alcohols.

Use of catalysts

While the traditional Meyer–Schuster rearrangement uses harsh conditions with a strong acid as the catalyst, this introduces competition with the Rupe reaction if the alcohol is tertiary.[2] Milder conditions have been used successfully with transition metal-based and Lewis acid catalysts (for example, Ru-[11] and Ag-based[12] catalysts). Cadierno et al. report the use of microwave-radiation with InCl as a catalyst to give excellent yields with short reaction times and remarkable stereoselectivity.[13] An example from their paper is given below:

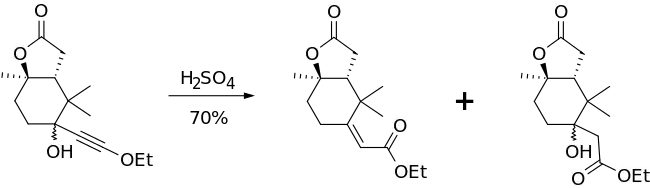

Applications

The Meyer–Schuster rearrangement has been used in a variety of applications, from the conversion of ω-alkynyl-ω-carbinol lactams into enamides using catalytic PTSA[14] to the synthesis of α,β-unsaturated thioesters from γ-sulfur substituted propargyl alcohols[15] to the rearrangement of 3-alkynyl-3-hydroxyl-1H-isoindoles in mildly acidic conditions to give the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.[16] One of the most interesting applications, however, is the synthesis of a part of paclitaxel in a diastereomerically-selective way that leads only to the E-alkene.[17]

The step shown above had a 70% yield (91% when the byproduct was converted to the Meyer-Schuster product in another step). The authors used the Meyer–Schuster rearrangement because they wanted to convert a hindered ketone to an alkene without destroying the rest of their molecule.

References

- Meyer, K. H.; Schuster, K. Ber. 1922, 55, 819.(doi:10.1002/cber.19220550403)

- Swaminathan, S.; Narayan, K. V. "The Rupe and Meyer-Schuster Rearrangements" Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 429–438. (Review)

- Vartanyan, S. A.; Banbanyan, S. O. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1967, 36, 670. (Review)

- Engel, D.A.; Dudley, G.B. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry 2009, 7, 4149–4158. (Review)

- Li, J.J. In Meyer-Schuster rearrangement; Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Reaction Mechanisms; Springer: Berlin, 2006; pp 380–381.(doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01053-8_159)

- Edens, M.; Boerner, D.; Chase, C. R.; Nass, D.; Schiavelli, M. D. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 3403–3408. (doi:10.1021/jo00441a017)

- Andres, J.; Cardenas, R.; Silla, E.; Tapia, O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 666–674. (doi:10.1021/ja00211a002)

- Tapia, O.; Lluch, J.M.; Cardena, R.; Andres, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 829–835. (doi:10.1021/ja00185a007)

- Rupe, H.; Kambli, E. Helv. Chim. Acta 1926, 9, 672. (doi:10.1002/hlca.19260090185)

- Li, J.J. In Rupe rearrangement; Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Reaction Mechanisms; Springer: Berlin, 2006; pp 513–514.(doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01053-8_224)

- Cadierno, V.; Crochet, P.; Gimeno, J. Synlett 2008, 1105–1124. (doi:10.1055/s-2008-1072593)

- Sugawara, Y.; Yamada, W.; Yoshida, S.; Ikeno, T.; Yamada, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12902-12903. (doi:10.1021/ja074350y)

- Cadierno, V.; Francos, J.; Gimeno, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 4773–4776.(doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.06.040)

- Chihab-Eddine, A.; Daich, A.; Jilale, A.; Decroix, B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2000, 37, 1543–1548.(doi:10.1002/jhet.5570370622)

- Yoshimatsu, M.; Naito, M.; Kawahigashi, M.; Shimizu, H.; Kataoka, T. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 4798–4802.(doi:10.1021/jo00120a024)

- Omar, E.A.; Tu, C.; Wigal, C.T.; Braun, L.L. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1992, 29, 947–951.(doi:10.1002/jhet.5570290445)

- Crich, D.; Natarajan, S.; Crich, J.Z. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 7139–7158.(doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00411-0)