Mi Fu

Mi Fu (Chinese: 米芾 or 米黻; pinyin: Mǐ Fú, also given as Mi Fei, 1051–1107)[1] was a Chinese painter, poet, and calligrapher born in Taiyuan during the Song dynasty. He became known for his style of painting misty landscapes. This style would be deemed the "Mi Fu" style and involved the use of large wet dots of ink applied with a flat brush. His poetry was influenced by Li Bai and his calligraphy by Wang Xizhi.

| Mi Fu | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mi Fu as depicted in a 1107 painting by Chao Buzhi | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 米芾 or 米黻 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 미불 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | べいふつ | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Mi Fu is regarded as one of the four greatest calligraphers of the Song dynasty. His style is derived from calligraphers in earlier dynasties, although he developed unique traits of his own.

As a personality, Mi Fu was noted as an eccentric. At times, they even deemed him "Madman Mi" because he was obsessed with collecting stones. He was also known as a heavy drinker. His son, Mi Youren, also became a well known painter following in his father's artistic style.

Biography

Mi Fu was a fifth-generation descendant of Mi Xin, a Later Zhou and early Song dynasty general from the Kumo Xi tribe that descended from the Xianbei.[2] He showed early signs of interest in arts and letters, as well as unusual memory skills.

His mother worked as a midwife and later as a wet-nurse, looking after the Emperor Shenzong (who was to start his reign in 1051 and continue until 1107).

Mi Fu knew the imperial family and he lived in the privileged location of the royal palaces, where he also started his career as Reviser of Books, Professor of Painting and Calligraphy in the capital, Secretary to the Board of Rites and Military Governor of Huaiyang. Mi Fu openly criticized conventional regulations of the time, causing him to move between jobs frequently.

Mi Fu collected old writings and paintings as his family wealth gradually diminished. Gradually his collection became of high value. He also inherited some of the calligraphies from his collection. He wrote:

When a man of today obtains such an old sample it seems to him as important as his life, which is ridiculous. It is in accordance with human nature, that things which satisfy the eye, when seen for a long time become boring; therefore they should be exchanged for fresh examples, which then appear double satisfying. That is the intelligent way of using pictures.

He arranged his collection in two parts, one of which was kept secret (or shown only to a few selected friends) and another which could be shown to visitors.

In his later years, Mi Fu became very fond of Holin Temple (located on Yellow Crane Mountain (黃鶴樓)). He later asked to be buried at its gate. Today the temple is gone, but his grave remains.[3]

Historical background

After the rise of landscape painting, creative activities followed which were of a more general kind and included profane, religious figure, bird, flower and bamboo painting besides landscapes. It was all carried out by men of high intellectual standards. To most of these men, painting was not a professional occupation but only one of the means by which they expressed their intellectual reactions to life and nature in visible symbols. Poetry and illustrative writing were in a sense even more important to them than painting and they made their living as more or less prominent government officials if they did not depend on family wealth. Even if some of them were real masters of ink-painting as well as of calligraphy, they avoided the fame and position of professional artists and became known as “gentleman-painters”. Artistic occupations such as calligraphy and painting were to these men activities to be done during the leisure time from official duties or practical occupations. Nevertheless, the foundation of their technical mastery was in writing, training in calligraphy which allowed them to transmit their thoughts with the same easiness in symbols of nature as in conventional characters. Their art became therefore a very intimate kind of expression, or idea-writing as it was called in later times. The beauty of this art was indeed closely connected to the visible ease with which it was produced, but which after all could not be achieved without intense training and deep thought.

Mi Fu was one of the highly gifted gentleman-painters. He was not a poet or philosopher, nevertheless, he was brilliant intellectually. With his very keen talent of artistic observation together with sense of humor and literary ability, he established for himself a prominent place among Chinese art-historians; his contributions in this field are still highly valued because they are based on what he had seen with his own eyes and not simply on what he had heard or learned from his forerunners. Mi Fu had the courage to express his own views, even when these were different from the prevailing ones or official opinions. His notes about painting and calligraphy are of great interest to art historians because they are spontaneous expressions of his own observations and independent ideas that help to characterize himself as well as the artists whose works he discusses.

Art

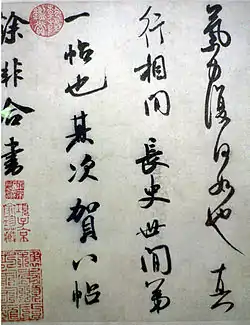

He is considered one of the most important representatives of the ‘Southern School’ (南宗畫) of landscape painting. Unfortunately, it is no longer possible clearly to say this from the pictures which passed under his name – there is no lack of such works, and most of them represent a rather definite type or pictorial style which existed also in later centuries, but to what extent they can be considered as Mi Fu's own creations is still a question. In other words, the general characteristics of his style are known, but it is not possible to be sure that the paintings ascribed to him represent the rhythm and spirit of his individual brush work as is possible with his authentic samples of calligraphy, which still exist. Therefore, he is more remembered as a skilled calligraphist and for his influence as a critic and writer on art rather than a skilled landscape painter.

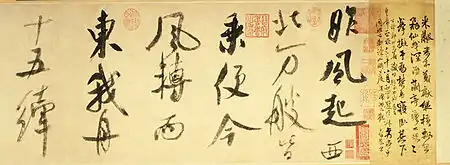

Mi Fu was among those for whom writing or calligraphy was intimately connected with the composing of poetry or sketching. It required an alertness of mind and spirit, which he thought was best achieved through the enjoyment of wine. Through this he reached a state of excitement rather than drunkenness. A friend of Mi Fu, Su Shih (蘇軾) admired him and wrote that his brush was like a sharp sword handled skillfully in fight or a bow which could shoot the arrow a thousand li, piercing anything that might be in its way. “It was the highest perfection of the art of calligraphy”, he wrote.

Other critics claimed that only Mi Fu could imitate the style of the great calligraphists of the Six Dynasties. Mi Fu indeed seems to have been an excellent imitator; some of these imitations were so good that they were taken for the originals. Mi Fu's son also testified that his father always kept some calligraphic masterpiece of the Tang or the Qin period in his desk as a model. At night he would place it in a box at the side of his pillow.

According to some writings, Mi Fu did most of his paintings during the last seven years of his life, and he himself wrote that “he chose as his models the most ancient masters and painted guided by his own genius and not by any teacher and thus represented the loyal men of antiquity.”

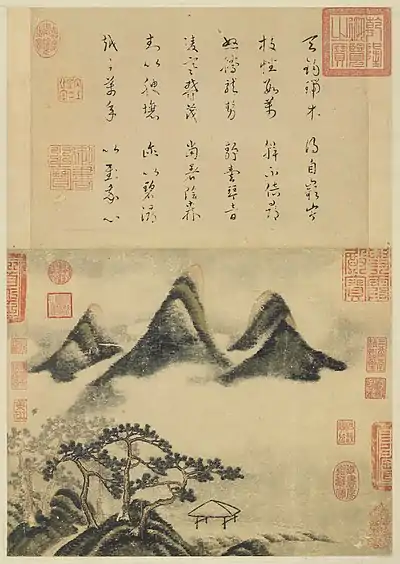

The pictures which still pass under the name of Mi Fu represent ranges of wooded hills or cone-shaped mountain peaks rising out of layers of woolly mist. At their feet may be water and closer towards the foreground clusters of dark trees. One of the best known examples of this kind of Mi Fu style is the small picture in the Palace Museum known as Spring Mountains and Pine-Trees. It is in the size of a large album-leaf, but at the top of the picture is added a poem said to be by the emperor Emperor Gaozong of Song. The mountains and the trees rise above a layer of thick mist that fills the valley; they are painted in dark ink tones with a slight addition of color in a plummy manner that hides their structure; it is the mist that is really alive. In spite of the striking contrast between the dark and the light tones the general effect of the picture is dull, which may be the result of wear and retouching.

Among the pictures which are attributed to Mi Fu, there apparently are imitations, even if they are painted in a similar manner with a broad and soft brush. They may be from Southern Song period, or possibly from the Yuan period, when some of the leading painters freely utilized the manner of Mi Fu for expressing their own ideas. The majority are probably from the later part of Ming period, when a cult of Mi Fu followers that viewed him as the most important representative of the "Southern School" started. Mi Fu himself had seen many imitations, perhaps even of his own works and he saw how wealthy amateurs spent their money on great names rather than on original works of art. He wrote: “They place their pictures in brocade bags and provide them with jade rollers as if they were very wonderful treasures, but when they open them one cannot but break out into laughter.”

Mi Fu's own manner of painting has been characterized by writers who knew it through their own observation or through hearsay. It is said that he always painted on paper which had not been prepared with gum or alum (alauns); never on silk or on the wall. In addition, he did not necessarily use the brush in painting with ink; sometimes he used paper sticks or sugar cane from which the juice had been extracted, or a calyx (kauss) of the lotus.

Even if Mi Fu was principally a landscape painter, he also did portraits and figure paintings of an old fashioned type. Nevertheless, he must have spent more time studying samples of ancient calligraphy and painting than producing pictures of his own. His book on "History of Painting" contains practical hints as to the proper way of collecting, preserving, cleaning and mounting pictures. Mi Fu was no doubt an excellent connoisseur who recognized quality in art, but in spite of his oppositional spirit, his fundamental attitude was fairly conventional. He appreciated some of the well recognized classics among the ancient masters and had little use for any of the contemporary painters. He had sometimes difficulty in admitting the values of others and found more pleasure in making sharp and sarcastic remarks than in expressing his thoughts in a just and balanced way.

Landscape painting was, to Mi Fu, superior to every other kind of painting; revealing his limitations and romantic flight: “The study of Buddhist paintings implies some moral advice; they are of a superior kind. Then follow the landscapes, then pictures of bamboo, trees, walls and stones, and then come pictures of flowers and grass. As to pictures of men and women, birds and animals, they are for the amusement of the gentry and do not belong to the class of pure art treasures.”

Notes

- Barnhart: 373. His courtesy name was Yuanzhang (元章) with several sobriquets: Nangong (南宮), Lumen Jushi (鹿門居士), Xiangyang Manshi (襄陽漫士), and Haiyue Waishi (海岳外史)

- Sturman, Peter Charles (1997). Mi Fu. Yale University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-300-06569-5.

- Red Pine. Poems of the Masters, p. 127. Copper Canyon Press 2003.

References

- Rhonda and Jeffrey Cooper (1997). Masterpieces of Chinese Art (page 76), by Rhonda and Jeffrey Cooper, Todtri Productions. ISBN 1-57717-060-1.

- Xiao, Yanyi, "Mi Fu". Encyclopedia of China (Arts Edition), 1st ed.

- Barnhart, R. M. et al., Three thousand years of Chinese painting. New Haven, Yale University Press. (1997). Page 373. ISBN 0-300-07013-6

External links

- Mi Fu and his Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mi Fu. |

- "米芾的書畫世界 The Calligraphic World of Mi Fu's Art". Taipei: National Palace Museum. 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-09-23.