Michelangelo phenomenon

The Michelangelo phenomenon is an interpersonal process observed by psychologists in which close, romantic partners influence or ‘sculpt’ each other.[1] Over time, the Michelangelo effect causes individuals to develop towards what they consider their “ideal selves”. This happens because their partner sees them and acts around them in ways that promote this ideal.

The phenomenon is referred to in contemporary marital therapy. Recent popular work in couples therapy and conflict resolution points to the importance of the Michelangelo phenomenon. Diana Kirschner[2] reported that the phenomenon was common among couples reporting high levels of marital satisfaction.

It is the opposite of the Blueberry phenomenon “in which interdependent individuals bring out the worst in each other.”[3] The Michelangelo phenomenon is related to the looking-glass self concept introduced by Charles Horton Cooley in his 1902 work Human Nature and the Social Order.[4]

Description

The model

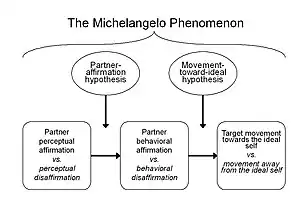

The Michelangelo phenomenon describes a three-step confirmation process in which an individual affirms their partner's ideal self and thereby helps move them towards their ideal self.

1. An individual sees their partner as the partner's own ideal self

2. The individual behaves around their partner in a way that elicits qualities in the partner they themselves consider ideal

3. This leads to the partner moving towards and realising their ideal self

The model posits a close romantic partner rather than a friend or acquaintance because they are "especially likely to yield strong confirmation effects."[5][6]

Partner affirmation

A couple of concepts are understood to constitute the Michelangelo phenomenon. The model relies on behavioural confirmation as the principle force that shapes the self. In interdependent relationships, behavioural confirmation takes place when the ideas and expectations an individual has of their partner come to be realised in the partner because of the individual's behaviour.

The Michelangelo phenomenon requires that individuals see their partner as their partner's self-conceived ideal. This entails partner perceptual affirmation, or the degree to which an individual's perception of their partner corresponds with their partner's ideal self. It also requires partner behavioural affirmation which refers to whether the behaviour of an individual brings out qualities in their partner that the partner themselves see as ideal.

Both perceptual and behavioural aspects of partner affirmation can take place consciously or unconsciously.[7] For example, someone with a partner who wants to be more sociable may consciously encourage them to spend more time with their friends, in an effort to help them meet this goal. This is conscious behavioural affirmation. On the other hand, knowing that sociability is a goal of their partner, someone may feel less apprehension when organising a social gathering in their space. This would inadvertently give the partner an opportunity to socialise and is an example of unconscious behavioural affirmation.

Movement towards the ideal self

According to the Michelangelo phenomenon, affirmation from a partner helps individuals move towards their ideal self. Stephen Drigotas (et al.) uses insights from interdependence theory to explain how partner affirmation leads to movement towards the ideal self. An affirming partner may shape someone through a series of selection mechanisms:[1]

- Retroactive selection in which an individual reinforces behaviours of their partner by punishing or rewarding them

- Preemptive selection wherein an individual initiates an interaction that promotes certain behaviours in their partner

- Situation selection where an individual creates a situation in which the elicitation of desired partner behaviours is probable

Partner disaffirmation and movement away from the ideal self

It is also possible for the inverse of the Michelangelo phenomenon to take place. A partner may in fact disaffirm their partner's ideal self and in doing so facilitate a movement away from their ideal self. An individual may disaffirm their partner “by communicating indifference, pessimism, or disapproval, by undermining [their] ideal pursuits, or by affirming qualities that are antithetical to [their] ideal self."[7] This disaffirmation may occur passively, in the failure to affirm, or actively, in disaffirmation.[1]

The metaphor

The phenomenon is named after the Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet and engineer Michelangelo (1475-1564). Michelangelo “described sculpting as a process whereby the artist released a hidden figure from the block of stone in which it slumbered.”[1] The metaphor of chipping away at a block of stone to reveal the ‘ideal form’, which extends to close relationships. According to the Michelangelo phenomenon, a person will be ‘sculpted’ into their self-conceived ideal form by their partner. The metaphor and term was first introduced by the US psychologist Stephen Michael Drigotas (et al.) in 1999.

Personal and couple well-being

Evidence suggests the Michelangelo phenomenon is conducive to both personal well-being[5] and the well-being of relationships.[1][5] The increased personal well-being is believed to be due to individuals being in a gratifying relationship and enjoying higher self-esteem. Well-being hypotheses are often incorporated into models that test the Michelangelo phenomenon.

Related phenomena

Growth-as-hell model

In contrast, it has been posited by Guggenbühl-Craig that it is precisely through disaffirmation that we grow and move towards our ideal-selves. This is because it is through disaffirmation that we are made aware of our flaws and can overcome them.[1] Much like the Michelangelo phenomenon, this growth-as-hell model of self-growth and movement towards the ideal self is understood to occur most potently in close, romantic relationships.

The Pygmalion phenomenon

The Pygmalion phenomenon, similar to a self-fulfilling prophecy, occurs when someone's belief about how a person should be informs their behaviour towards them, which in turn shapes the person's actual behaviour and self. This could take place in a close relationship.[7] For example, an individual's ideal self might be someone who is conscientious and as a consequence affirm that conscientious quality in their partner and shape their behaviour. Where the Michelangelo phenomenon brings out the 'sculpture's ideal', the Pygmalion phenomenon instead brings the 'sculptor's ideal' into being. For the person being 'sculpted', this can be seen as a movement away from their own ideal self and therefore the process would not enhance personal or couple well-being according to the model of the Michelangelo phenomenon.

References

- Drigotas, Stephen M.; Rusbult, Caryl E.; Wieselquist, Jennifer; Whitton, Sarah W. (1999). "Close partner as sculptor of the ideal self: Behavioral affirmation and the Michelangelo phenomenon". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77 (2): 293–323. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.293. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 10474210.

- Kirschner, Diana Adile (2014-07-02). Sealing the deal : the love mentor's guide to lasting love. ISBN 9781609416959. OCLC 860833193.

- Anghel, Teodora C. (September 2016). "Emotional Intelligence and Marital Satisfaction". Journal of Experimential Psychotherapy. 19: 75.

- Charles Horton Cooley (2018). Human Nature And The Social Order. 开放图书馆. ISBN 978-9600040005. OCLC 1078575196.

- Drigotas, Stephen M. (February 2002). "The Michelangelo Phenomenon and Personal Well-Being". Journal of Personality. 70 (1): 59–77. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00178. ISSN 0022-3506. PMID 11908536.

- Bühler, Janina Larissa; Weidmann, Rebekka; Kumashiro, Madoka; Grob, Alexander (2018-03-27). "Does Michelangelo care about age? An adult life-span perspective on the Michelangelo phenomenon". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 36 (4): 1392–1412. doi:10.1177/0265407518766698. ISSN 0265-4075.

- Rusbult, Caryl E.; Finkel, Eli J.; Kumashiro, Madoka (December 2009). "The Michelangelo Phenomenon" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 18 (6): 305–309. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01657.x. ISSN 0963-7214.