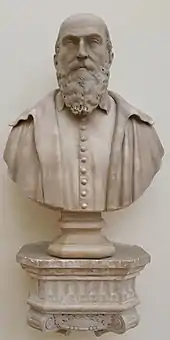

Michele Sanmicheli

Michele Sanmicheli (also spelled Sanmmicheli, Sanmichele or Sammichele) (1484–1559), was a Venetian architect and urban planner of Mannerist-style, among the greatest of his era. A tireless worker, he was in charge of designing buildings and religious buildings of great value.

Hired by the Serenissima as a military architect, he designed also numerous fortifications in the extensive Venetian Empire, thus ensuring a great reputation. In fact, not only in Italy, where you can find his works in Venice, Verona, Bergamo and Brescia, he worked also in Dalmatia, Zadar (Zara), Šibenik, Crete and Corfu. He was probably the only practicing Venetian architect of the sixteenth century to have had the opportunity to study Greek architecture, a possible source of inspiration for the use of Doric columns without bases.

Biography

Sanmicheli was born in San Michele, a quarter of Verona, which at the time was part of the Venetian Terra ferma. He learnt the elements of his profession from his father Giovanni and his uncle Bartolomeo, who both practised successfully as builder-architects in Verona. Like Jacopo Sansovino he was a salaried official of the Republic of Venice, but unlike Sansovino, his commissions lay in Venetian territories outside Venice; he was no less distinguished as a military architect, and was employed in strengthening Venetian fortifications in several cities of Crete and most notably Candia, Dalmatia and Corfu as well as a great fort at the Lido, guarding the sea entrance to the Venetian lagoon.

He went at an early age to Rome, probably to work as an assistant to Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, where he had opportunities to study classic sculpture and architecture. In 1509 he went to Orvieto where he practiced for the next two decades. Among his earliest works are the first design of the duomo of Montefiascone, initiated in 1519, an octagonal building surmounted with a dome,[1] and the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, he designed and built the funerary chapel for the Petrucci family in the Gothic church of San Domenico in Orvieto. Several palazzi at both places are attributed to him.

Sanmicheli was in Verona by 1527 at the latest, working on the monumental cannon-resistant city gates; he began to transform the fortifications of Verona according to the newer system of corner bastions, a system for the advancement of which he did much valuable service. Sanmicheli built two massively fortified and richly decorated city gates for Verona, the Porta Nuova and the Porta Palio, in which the richest possible Roman Doric is superimposed against layers of rustication. Giorgio Vasari's impression was that "in these two gates it may truly be seen that the Venetian Senate made full use of the architect's powers and equalled the buildings and works of the ancient Romans[2] – the constant aim and ultimate goal of the Renaissance architects. He also regularised the Piazza Brà, opening up a vista to the Arena.

Works

He found time to spare from his official commissions to build three palazzi in Verona that have been central to his reputation, though documentation has proved elusive. These are:

- Palazzo Pompei (probably begun around 1530) is an enriched version of Bramante's House of Raphael. The entrance has been moved to the center of a seven-bay façade[3] and given a slightly wider central bay; in order to prevent the composition from rifting apart, the corner columns of the outermost bays are stressed by being doubled with square pilasters.

- Palazzo Canossa (under construction in 1537), with another seven-bay front, has a triple-arched central entrance in a high rusticated basement that is pierced by low mezzanine windows. In the piano nobile arch-headed windows are framed by doubled pilasters, so that each bay reads as a unit complete in itself, while the arch imposts are emphasized by a moulding that appears to run continuously behind the pilasters, to tie together the sequence of bays. There is a second mezzanine above the piano nobile, under a powerfully projecting cornice capped with a balustrade, with a skyline of figural sculptures. Strong mouldings continue the imposts of the arched openings and windows. The palazzo wraps round a three-sided court open to the Adige on the fourth side.

- Palazzo Bevilacqua (under construction in 1529), the most famous of the three and often cited as an exemplar of Mannerism in architecture, is the richest façade of its generation, rivalling Giulio Romano's Palazzo Te. Its complex superimposed layers, its alternating superimposed rhythms of large and small bays and straight and spiralling fluting, the rich carved decor in its keystones and in the spandrels of the piano nobile arches, climax in the rich sculpture of its corbelled cornice.

One of Sanmicheli's most graceful designs is the Cappella Pellegrini in the church of San Bernardino at Verona, where the cylindrical exterior masks a domed interior that rearranges elements of the Pantheon. His other works include Palazzo Corner a San Polo and Palazzo Grimani di San Luca in Venice, the Porta Terraferma in Zadar and the funerary Petrucci Chapel in the church of San Domenico in Orvieto.

Beside the Ponte Nuovo in Verona (demolished in the late 19th century), his last work, begun in 1559, was the Santuario di Madonna di Campagna (or Santa Maria della Pace), formerly outside Verona on the road to Venice. The cylindrical church, with a band of blind and windowed arcading under a wide plain frieze, crowned with a dome, was probably modified during its construction by Bernardino Brugnoli.[4][5][6]

Notes

- The Montefiascone duomo was not completed until 1843. The great dome is not Sanmicheli's; it was designed by Carlo Fontana towards the end of the 17th century but left unfinished for more than a century; the Neoclassical façade and the campanili are 19th-century.

- Quoted in Murray, p. 180.

- In Bramante's House of Raphael, the ground floor was given over to premises for shops.

- The book that was mistaken for Sanmicheli's own in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica was Li cinque ordini dell' architettura civile di Michel Sanmicheli, printed at Verona in 1735 by conte Alessandro Pompei, the heir of Sanmicheli's patron who lived in Palazzo Pompei, Verona. Pompei was a noble amateur architect with links to the circle of Scipione Maffei. Noting the lack of existing drawings by Sanmicheli, and the absence of theoretical contributions on his part, Pompei analyzed Sanmicheli’s use of the orders of architecture, comparing them with those of the outstanding published masters, Vignola, Serlio and Palladio. His publication attracted the attention of a young generation of neoclassical architects to the forgotten Michele Sanmichele. In 1862 measured drawings published by Francesco Ronzani and Girolamo Luciolli inaugurated the modern reappraisal of his work. The work was published as three folio volumes, with a portrait frontispiece and 150 engraved plates.

- Alessandro Pompei, Li cinque ordini d'architettura civile di Michele Sanmicheli non più veduti in luce, ora publicati, ed esposti con quelli di Vitruvio e d'altri cinque, Verona, 1735

- Michele Sanmicheli; Francesco Zanotto; Francesco Ronzani; Girolamo Luciolli. Le Fabbriche Civili, Ecclesiastiche e Militari di Michele Sanmicheli, Disegnate ed Incisi da Francesco Ronzani e Girolamo Luciolli, con Testo Illustrativo Riveduto da Francesco Zanotto. (Turin 1862) OCLC 8653304

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sanmichele, Michele". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sanmichele, Michele". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Peter J. Murray, 1963. The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance (Batsford)

Further reading

- Eric Langenskiöld, 1938. Michele Sanmicheli: The Architect of Verona. His Life and Works (Uppsala; in English)

- Michele Sanmicheli, 1960. Micheli Sanmicheli: Catalogo (della mostra, maggio-ottobre 1960, Palazzo Canossa, Verona), Venezia: Neri Pozza. OCLC 637072811

- Paul Davies and David Hemsoll Michele Sanmicheli], Milan, Electa, 2004, ISBN 88-370-2804-0, 404 pages, 440 ill. (in Italian, translated by Antonella Bergamin).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michele Sanmicheli. |