Mimar Sinan

Mimar Sinan (Ottoman Turkish: معمار سينان, romanized: Mi'mâr Sinân, Turkish: Mimar Sinan, pronounced [miːˈmaːɾ siˈnan]) c. 1488/1490 – July 17, 1588) was the chief Ottoman architect (Turkish: mimar) and civil engineer for sultans Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, and Murad III. Known as Koca Mi'mâr Sinân Âğâ, "Sinan Agha the Grand Architect", he was responsible for the construction of more than 300 major structures and other more modest projects, such as schools. His apprentices would later design the Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul and Stari Most in Mostar.

Mimar Sinan | |

|---|---|

A pencil portrait of Mimar Sinan | |

| Born | c. 1488/1490 |

| Died | July 17, 1588 (aged 97–100) |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Süleymaniye Mosque Selimiye Mosque Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge Mihrimah Sultan Mosque Mihrimah Mosque Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex Şehzade Mosque Haseki Hürrem Sultan Baths Haseki Sultan Complex Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque |

| Signature | |

| |

The son of a stonemason, he received a technical education and became a military engineer. He rose rapidly through the ranks to become first an officer and finally a Janissary commander, with the honorific title of ağa.[1] He refined his architectural and engineering skills while on campaign with the Janissaries, becoming expert at constructing fortifications of all kinds, as well as military infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges and aqueducts.[2] At about the age of fifty, he was appointed as chief royal architect, applying the technical skills he had acquired in the army to the "creation of fine religious buildings" and civic structures of all kinds.[2] He remained in this post for almost fifty years.

His masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, although his most famous work is the Suleiman Mosque in Istanbul. He headed an extensive governmental department and trained many assistants who, in turn, distinguished themselves, including Sedefkar Mehmed Agha, architect of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque. He is considered the greatest architect of the classical period of Ottoman architecture and has been compared to Michelangelo, his contemporary in the West.[3][4] Michelangelo and his plans for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome were well known in Istanbul, since Leonardo da Vinci and he had been invited, in 1502 and 1505 respectively, by the Sublime Porte to submit plans for a bridge spanning the Golden Horn.[5] Mimar Sinan's works are among the most influential buildings in history.[6]

Early years and background

According to contemporary biographer, Mustafa Sâi Çelebi, Sinan was born in 1489 (c. 1490 according to the Encyclopædia Britannica,[7] 1491 according to the Dictionary of Islamic Architecture and some time between 1494 and 1499, according to the Turkish professor and architect Reha Günay)[8] with the name Joseph. He was born either an Armenian,[9][10][11][12][13][14] Cappadocian Greek,[15][16][17][18][19][20][21] Albanian,[22][23][24] or a Christian Turk[25] in a small town called Ağırnas near the city of Kayseri in Anatolia (as stated in an order by Sultan Selim II).[26] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Sinan had either Armenian or Greek origin.[7] One argument that lends credence to his Armenian or Greek background is a decree by Selim II dated Ramadan 7 981 (ca. Dec. 30, 1573), which grants Sinan's request to forgive and spare his relatives from the general exile of Kayseri's Armenian communities to the island of Cyprus;[12][27] while Godfrey Goodwin stated that "after the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571, when Selim II decided to repopulate the island by transferring Rum (Orthodox Christian) families from the Karaman Eyalet, Sinan intervened on behalf of his family and obtained two orders from the Sultan in council exempting them from deportation."[20]

According to some scholars, this means that his family was Cappadocian Greek because the only Orthodox Christians (Rûms) of the region were Greek-speaking.[28][29]

According to Herbert J. Muller though, he "seems to have been an Armenian."[30] Lucy Der Manuelian of Tufts University suggests that "he can be identified as an Armenian through a document in the imperial archives and other evidence."[31]

Several scholars have cited Sinan's possible Albanian origin.[22] According to the British scholar Percy Brown and the Indian scholar Vidya Dhar Mahajan, the Mughal Emperor Babur was very dissatisfied with the local Indian architecture and planning, thus he invited "certain pupils of the leading Ottoman architect Sinan, the Albanian genius, to carry out his architectural schemes.".[32][33]

Sinan grew up helping his father in his work, and by the time that he was conscripted would have had a good grounding in the practicalities of building work.[34] There are three brief records (Anonymous Text; Architectural Masterpieces; Book of Architecture) in the library of Topkapı Palace, dictated by Sinan to his friend and biographer Mustafa Sâi Çelebi. In these manuscripts, Sinan divulges some details of his youth and military career. His father is referred to as "Abdülmennan" (literally "Servant of the Generous and Merciful One"), a title which was commonly used in the Ottoman period to define the non-Muslim father of a Muslim convert.[8]

Military career

In 1512, Sinan was conscripted into Ottoman service under the devshirme system.[26][35] He was sent to Constantinople to be trained as an officer of the Janissary Corps and converted to Islam.[26] He was too old to be admitted to the imperial Enderun School in the Topkapı Palace but was sent instead to an auxiliary school.[26] Some records claim that he might have served the Grand Vizier Pargalı İbrahim Pasha as a novice of the Ibrahim Pasha School. Possibly, he was given the Islamic name Sinan there. He initially learned carpentry and mathematics but through his intellectual qualities and ambitions, he soon assisted the leading architects and got his training as an architect.[26]

During the next six years, he also trained to be a Janissary officer (acemioğlan). He possibly joined Selim I in his last military campaign, Rhodes according to some sources, but when the Sultan died, this project ended. Two years later he witnessed the conquest of Belgrade. Under the new sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, he was present, as a member of the Household Cavalry, at the Battle of Mohács. He was promoted to captain of the Royal Guard and then given command of the Infantry Cadet Corps. He was later stationed in Austria, where he commanded the 62nd Orta of the Rifle Corps.[26] He became a master of archery, while at the same time, as an architect, learning the weak points of structures when gunning them down. In 1535 he participated in the Baghdad campaign as a commanding officer of the Royal Guard. In 1537 he went on expeditions to Corfu and Apulia and Moldavia.[36]

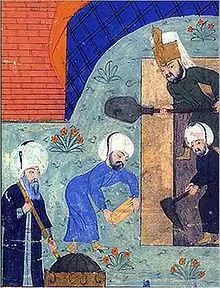

During these campaigns he proved himself an able architect and engineer. When the Ottoman army captured Cairo, Sinan was promoted to chief architect and was given the privilege of tearing down any buildings in the captured city that were not according to the city plan. During the campaign in the East, he assisted in the building of defences and bridges, such as a bridge across the Danube. He converted churches into mosques. During the Persian campaign in 1535 he built ships for the army and the artillery to cross Lake Van. For this he was given the title Haseki'i, Sergeant-at-Arms in the body guard of the Sultan, a rank equivalent to that of the Janissary Ağa.

When Chelebi Lütfi Pasha became Grand Vizier in 1539, he appointed Sinan, who had previously served under his command, to the office of Architect of the Abode of Felicity. This was the start of a remarkable career. The job entailed the supervision infrastructure construction and the flow of supplies within the Ottoman Empire. He was also responsible for the design and construction of public works, such as roads, waterworks and bridges. Through the years he transformed his office into that of Architect of the Empire, an elaborate government department, with greater powers than his supervising minister. He became the head of a whole Corps of architects, training a team of assistants, deputies and pupils.

Work

His training as an army engineer gave Sinan an empirical approach to architecture rather than a theoretical one. But the same can be said of the great Western Renaissance architects, such as Brunelleschi and Michelangelo.

Various sources state that Sinan was the architect of at least 374 structures which included 92 mosques; 52 small mosques (mescit); 55 schools of theology (medrese); 7 schools for Koran reciters (darülkurra); 20 mausoleums (türbe); 17 public kitchens (imaret); 3 hospitals (darüşşifa); 6 aqueducts; 10 bridges; 20 caravanserais; 36 palaces and mansions; 8 vaults; and 48 baths.[37] Sinan held the position of chief architect of the palace, which meant being the overseer of all construction work of the Ottoman Empire, for nearly 50 years, working with a large team of assistants consisting of architects and master builders.

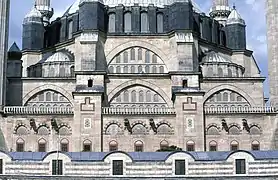

The development and maturing stages of Sinan's career can be illustrated by three major works. The first two of these are in Istanbul: the Şehzade Mosque, which he calls a work of his apprenticeship period and the Süleymaniye Mosque, which is the work of his qualification stage. The Selimiye Mosque in Edirne is the product of his master stage.

- Sinan's major works

Şehzade Mosque - Istanbul

Şehzade Mosque - Istanbul Şehzade Mosque interior

Şehzade Mosque interior Süleymaniye Mosque - Istanbul

Süleymaniye Mosque - Istanbul Süleymaniye Mosque interior

Süleymaniye Mosque interior Selimiye mosque - Edirne

Selimiye mosque - Edirne

Şehzade Mosque is the first of the grand mosques created by Sinan. The Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, which is also known as the Üsküdar Quay Mosque, was completed in the same year and has an original design with its main dome supported by three half domes. When Sinan reached the age of 70, he had completed the Süleymaniye Mosque complex. This building, situated on one of the hills of Istanbul facing the Golden Horn, and built in the name of Süleyman the Magnificent, is one of the symbolic monuments of the period. The diameter of the dome, which exceeds the 31 m (102 ft) of the Selimiye Mosque which Sinan completed when he was 80, is the most outstanding example of the level of achievement reached by Sinan. Mimar Sinan reached his artistic peak with the design, architecture, tile decorations and land stone workmanship displayed at Selimiye.

Another area of architecture where Sinan produced unique designs are his mausoleums. The Mausoleum of Şehzade Mehmed is notable for with its exterior decorations and sliced dome. The Rüstem Paşa mausoleum is a very attractive structure in classical style. The mausoleum of Süleyman the Magnificent is an interesting experiment, with an octagonal body and flat dome. The Selim II Mausoleum with has a square plan and is one of the best examples of Turkish mausoleum architecture. Sinan's own mausoleum, which is located in the north-east part of the Süleymaniye complex on the other hand, is a very plain structure.

Sinan masterfully combined art with functionalism in the bridges he built. The largest of these is the nearly 635 m (2,083 ft) long Büyükçekmece Bridge. Other important examples are the Ailivri Bridge, the Old Bridge in Svilengrad on the Maritsa, the Lüleburgaz (Sokullu Mehmet Pasha) Bridge on the Lüleburgaz River, the Sinanlı Bridge over the river Ergene and the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge over Drina river in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[38]

While Sinan was maintaining and improving the water supply system of Istanbul, he built arched aqueducts at several locations within the city. The Mağlova Arch over the Alibey River, which is 257 m (843 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) high, has two tiers of arches, and is one of the best examples of its kind.

At the start of Sinan's career, Ottoman architecture was highly pragmatic. Buildings were repetitions of former types and were based on rudimentary plans. They were more an assembly of parts than a conception of a whole. An architect could sketch a plan for a new building and an assistant or foreman knew what to do, because novel ideas were avoided. Moreover, architects used an extravagant margin of safety in their designs, resulting in a wasteful use of material and labour. Sinan would gradually change all this. He was to transform established architectural practices, amplifying and transforming the traditions by adding innovations, trying to approach perfection.

The early years (till the mid-1550s) : apprenticeship period

During these years he continued the traditional pattern of Ottoman architecture, but he gradually began exploring other possibilities, because during his military career he had had the opportunity to study the architectural monuments in the conquered cities of Europe and the Middle East.

His first opportunity to design a major building was the Hüsrev Pasha Mosque and its double medresse in Aleppo, Syria. It was built in the winter of 1536-1537 for his commander-in-chief and the governor of Aleppo between two army campaigns. It was built hastily and this is evident in the coarseness of execution and the crude decoration.

His first major commission as the royal architect was the construction of the Haseki Sultan Complex for Hurrem Sultan, the wife of the sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. He had to follow the plans drawn by his predecessors. Sinan retained the traditional arrangement of the available space without any innovations. Nevertheless, it was already better built than the Aleppo mosque and it shows a certain elegance. However, it has suffered from many restorations. Sinan is credited to have built a defensive tower in Vlorë, south Albania, in 1537, very similar to the White Tower of Thessaloniki,[39] as well as Muradie Mosque, during Suleiman the Magnificent's stay in the town for the preparation of his expedition towards Italy.[40][41]

In 1541, he started the construction of the mausoleum (türbe) of the Grand Admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa. It stands on the shore of Beşiktaş on the European part of Istanbul, at the site where his fleet used to assemble. Oddly enough, the admiral is not buried there, but in his türbe next to the Iskele mosque. This mausoleum has been severely neglected since then.

Mihrimah Sultan, the only daughter of Suleiman and Hurrem and wife of the Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha gave Sinan the commission to build a mosque with medrese (college), an imaret (soup kitchen) and a sibyan mekteb (Qur'an school) in Üsküdar. The imaret no longer exists. This Iskele Mosque (or Jetty mosque) already shows several hallmarks of Sinan's mature style: a spacious, high-vaulted basement, slender minarets, single-domed baldacchino, flanked by three semi-domes ending in three exedrae and a broad double portico. The construction was finished in 1548. The construction of a double portico was not a first in Ottoman architecture, but it set a trend for country mosques and mosques of viziers in particular. Rüstem Pasha and Mihrimah required them later in their three mosques in Constantinople and in the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Tekirdağ. The inner portico traditionally have stalactite capitals while the outer portico has capitals with chevron patterns (baklava).

When sultan Suleiman the Magnificent returned from another Balkan campaign, he received news that his son Ṣehzade Mehmed had died at the age of twenty-two. In November 1543, not long after Sinan had started the construction of the Iskele Mosque, the sultan ordered Sinan to build a new major mosque with an adjoining complex in memory of his favourite son. This Şehzade Mosque would become larger and more ambitious than his previous ones. Architectural historians consider this mosque as Sinan's first masterpiece. Obsessed by the concept of a large central dome, Sinan turned to the plans of mosques such as the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakır or the Piri Pasha Mosque in Hasköy. He must have visited both mosques during his Persian campaign. Sinan built a mosque with a central dome, this time with four equal half-domes. This superstructure is supported by four massive, but still elegant, free-standing octagonal fluted piers and four piers incorporated in each lateral wall. In the corners, above roof level, four turrets serve as stabilizing anchors. This coherent concept already is markedly different from the additive plans of traditional Ottoman architecture. Sedefkar Mehmed Agha would later copy the concept of fluted piers in his Sultan Ahmed Mosque in an attempt to lighten their appearance. Sinan, however, rejected this solution in his next mosques.

Mid-1550s to 1570: qualification stage

By 1550, Suleiman the Magnificent was at the height of his powers. Having built a mosque for his son, he felt it was time to construct his own imperial mosque, an enduring monument larger than all the others, to be built on a gently sloping hillside dominating the Golden Horn. Money was no problem, since he had accumulated a treasure from the loot of his campaigns in Europe and the Middle East. He gave the order to Sinan to build a mosque, the Süleymaniye, surrounded by a külliye consisting of four colleges, a soup kitchen, a hospital, an asylum, a hamam, a caravanserai and a hospice for travellers (tabhane). Sinan, now heading a formidable department with a great number of assistants, finished this formidable task in seven years. Before Süleymaniye, no mosques had been built with half cubic roofs. He got the idea of half cubic roof design from the Hagia Sophia. Through this monumental achievement, Sinan emerged from the anonymity of his predecessors. Sinan must have known the ideas of the Renaissance architect Leone Battista Alberti (who in turn had studied De architectura by the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius), since he too was concerned in building the ideal church, reflecting harmony through the perfection of geometry in architecture. But, contrary to his Western counterparts, Sinan was more interested in simplification than in enrichment. He tried to achieve the largest volume under a single central dome. The dome is based on the circle, the perfect geometrical figure representing, in an abstract way, a perfect God. Sinan used subtle geometric relationships, using multiples of two when calculating the ratios and the proportions of his buildings. However, in a later stage, he also used divisions of three or ratios of two to three when working out the width and the proportions of domes, such as the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque at Kadırga.

While he was fully occupied with the construction of the Süleymaniye, Sinan or his subordinates drew up the plans and gave instructions for many other constructions. Sinan built a mosque for the Grand Vizier Pargalı İbrahim Pasha and a mausoleum (türbe) at Silivrikapı (Constantinople) in 1551.

The next Grand Vizier, Rüstem Pasha gave Sinan several more commissions. In 1550 he built a large inn (han) in the Galata district of Istanbul. About ten years later he built another han in Edirne, and between 1544 and 1561 the Taṣ Han at Erzurum. He designed a caravanserai in Eregli and an octagonal madrasah in Constantinople.

Between 1553 and 1555, Sinan built the Sinan Pasha Mosque at Beşiktaş, a smaller version of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque at Edirne, for the Grand Admiral Sinan Pasha. This proves again that Sinan had thoroughly studied the work of other architects, especially since he was responsible for the upkeep of these buildings. He copied the old form, pondered over the weaknesses in the construction and tried to solve this with his own solution. In 1554, Sinan used the form of the Sinan Pasha mosque again for the construction of the mosque for the next Grand Vizier Kara Ahmet Pasha in Constantinople, his first hexagonal mosque. By using a hexagonal plan, Sinan could reduce the side domes to half-domes and set them in the corners at an angle of 45 degrees. Clearly, Sinan must have appreciated this form, since he repeated it later in mosques such as the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque at Kadırga and the Atik Valide Mosque at Üsküdar.

In 1556, Sinan built the Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı, replacing the antique Baths of Zeuxippus, which are still standing close to the Hagia Sophia. This would become one of the most beautiful hamams he ever constructed.

In 1559, he built the Cafer Ağa madrasah below the forecourt of the Hagia Sophia. In the same year he began the construction of a small mosque for Iskender Pasha at Kanlıka, beside the Bosphorus. This was one of the many minor and routine commissions the office of Sinan received over the years.

In 1561, when Rüstem Pasha died, Sinan began the construction of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque, as a memorial supervised by his widow Mihrimah Sultan. It is situated just below the Süleymaniye. This time the central form is octagonal, modelled on the monastery church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, with four small semi-domes set in the corners. In the same year, Sinan built a türbe for Rüstem Pasha in the garden of the Şehzade Mosque, decorated with the finest tiles Iznik could produce. Mihrimah Sultan, having doubled her wealth after the death of her husband, now wanted a mosque of her own. Sinan built the Mihrimah Mosque at Edirnekapı (Edirne Gate) for her on the highest of the seven hills of Constantinople. He raised the mosque on a vaulted platform, accentuating its hilltop site. There is some speculation concerning the dates; until recently this was supposed to be between 1540 and 1540, but now it is generally accepted to be between 1562 and 1565. Sinan, concerned with grandeur, built a mosque in one of his most imaginative designs, using new support systems and lateral spaces to increase the area available for windows. He built a central dome 37 m (121 ft) high and 20 m (66 ft) wide, supported by pendentives, on a square base with two lateral galleries, each with three cupolas. At each corner of this square stands a gigantic pier, connected with immense arches each with 15 large windows and four circular ones, flooding the interior with light. The style of this revolutionary building was as close to the Gothic style as Ottoman structure permits.

In 1566 Sinan completed the Banya Bashi Mosque in Sofia, Bulgaria, currently the only functioning mosque in the city. His first mosque in Sofia was built in 1528; popularly known as Imaret Mosque or Black Mosque due to the dark colour of its building stone, it was damaged by an earthquake and abandoned in the XIX century.

In the 1560s he built the Kirkcesme water supply system for Istanbul. It is seen as a masterpiece of his work. It spans 55 km and includes 35 aqueduct bridges, 4 of which are notable for their height (up to 35m) as well as their length (up to 700m).[42]

Between 1560 and 1566 Sinan built a mosque in Constantinople for Zal Mahmud Pasha on a hillside beyond Ayvansaray. Sinan certainly conceived the plans and partly supervised the construction, but left the building of lesser areas to less than competent hands, since Sinan and his most able assistants were about to begin his masterpiece, the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne. On the outside, the mosque rises high, with its east wall pierced by four tiers of windows. This gives the mosque an aspect of a palace or even a block of apartments. Inside, there are three broad galleries making the interior look compact. The heaviness of this structure makes the dome look unexpectedly lofty. These galleries look like a preliminary try-out for the galleries of the Selimiye Mosque.

The period from 1570 to his death: master stage

In this late stage of his life, Sinan tried to create unified and sublimely elegant interiors. To achieve this, he eliminated all the unnecessary subsidiary spaces beyond the supporting piers of the central dome. This can be seen in the Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque in Kadırga, Istanbul (1571–1572) and in the Selimiye mosque in Edirne. In other buildings of his final period, Sinan experimented with spatial and mural treatments that were new in the classical Ottoman architecture.

According to him from his autobiography "Tezkiretü’l Bünyan", his masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne. Breaking free of the handicaps of traditional Ottoman architecture, this mosque marks the climax of Sinan's work and of all classical Ottoman architecture. While it was being built, the architect's saying of "You can never build a dome larger than the dome of Hagia Sophia and specially as Muslims" was his main motivation. When it was completed, Sinan claimed that it had the largest dome in the world, leaving Hagia Sophia behind. In fact, the dome height from the ground level was lower and the diameter barely larger (0.5 meters, approximately 2 feet) than the millennium-older Hagia Sophia. However, measured from its base the dome of Selimiye is higher. Sinan was more than 80 years old when the building was finished. In this mosque he finally realized his aim of creating the optimum, completely unified, domed interior : a triumph of space that dominates the interior. He used this time an octagonal central dome (31.28 m wide and 42 m high), supported by eight elephantine piers of marble and granite. These supports lack any capitals but have squinches or consoles at their summit, leading to the optical effect that the arches seem to grow integrally out of the piers. By placing the lateral galleries far away, he increased the three-dimensional effect. The many windows in the screen walls flood the interior with light. The buttressing semi-domes are set in the four corners of the square under the dome. The weight and the internal tensions are hidden, producing an airy and elegant effect rarely seen under a central dome. The four minarets (83 m high) at the corners of the prayer hall are the tallest in the Muslim world, accentuating the vertical posture of this mosque that already dominates the city.

He also designed the Taqiyya al-Sulaimaniyya khan and mosque in Damascus, still considered one of the city's most notable monuments. He has also built Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad across the Drina River in the east of Bosnia and Herzegovina which is now UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Conclusion

At the start of his career as an architect, Sinan had to deal with an established, traditional domed architecture. His training as an army engineer led him to approach architecture from an empirical point of view, rather than from a theoretical one. He started to experiment with the design and engineering of single-domed and multiple-domed structures. He tried to obtain a new geometrical purity, a rationality and a spatial integrity in his structures and designs of mosques. Through all this, he demonstrated his creativity and his wish to create a clear, unified space. He started to develop a series of variations on the domes, surrounding them in different ways with semi-domes, piers, screen walls and different sets of galleries. His domes and arches are curved, but he avoided curvilinear elements in the rest of his design, transforming the circle of the dome into a rectangular, hexagonal or octagonal system. He tried to obtain a rational harmony between the exterior pyramidal composition of semi-domes, culminating in a single drumless dome, and the interior space where this central dome vertically integrates the space into a unified whole. His genius lies in the organization of this space and in the resolution of the tensions created by the design. He was an innovator in the use of decoration and motifs, merging them into the architectural forms as a whole. He accentuated the centre underneath the central dome by flooding it with light from the many windows. He incorporated his mosques in an efficient way into a complex (külliye), serving the needs of the community as an intellectual centre, a community centre and serving the social needs and the health problems of the faithful.

When Sinan died, classical Ottoman architecture had reached its climax. No successor was gifted enough to better the design of the Selimiye mosque and to develop it further. His students retreated to earlier models, such as the Şehzade mosque. Invention faded away, and a decline set in.

Constructions

During his tenure during 50 years of the post of imperial architect, Sinan is said to have constructed or supervised 476 buildings (196 of which still survive), according to the official list of his works, the Tazkirat-al-Abniya. He could not possibly have designed them all, but he relied on the skills of his office. He took credit and the responsibility for their work. For, as a janissary, and thus a slave of the sultan, his primary responsibility was to the sultan. In his spare time, he also designed buildings for the chief officials. He delegated to his assistants the construction of less important buildings in the provinces.

- 94 large mosques (camii),

- 57 colleges,

- 52 smaller mosques (mescit),

- 48 bath-houses (hamam).

- 35 palaces (saray),

- 22 mausoleums (türbe),

- 20 caravanserai (kervansaray; han),

- 17 public kitchens (imaret),

- 8 bridges,

- 8 store houses or granaries

- 7 Koranic schools (medrese),

- 6 aqueducts,

- 3 hospitals (darüşşifa)

Some of his works:

- Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque (Azapkapı)

- Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque (Kadırga)

- Caferağa Medresseh

- Selimiye Mosque in Edirne

- Süleymaniye Mosque

- Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex

- Molla Çelebi Mosque

- Haseki Baths

- Haseki Sultan Complex

- Çemberlitaş Baths

- Piyale Pasha Mosque

- Şehzade Mosque

- Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Edirnekapı

- Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Üsküdar

- Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad

- Banya Bashi Mosque in Sofia, Bulgaria

- Nisanci Mehmed Pasha Mosque

- Rüstem Pasha Mosque

- Zal Mahmud Pasha Mosque

- Kadirga Sokullu Mosque

- Koursoum Mosque or Osman Shah Mosque in Trikala

- Al-Takiya Al-Suleimaniya in Damascus

- Yavuz Sultan Selim Madras

- Mimar Sinan Bridge in Büyükçekmece

- Church of the Assumption in Uzundzhovo

- Tekkiye Mosque

- Khusruwiyah Mosque

- Oratory at the Western Wall

Death and Legacy

Sinan died in AH 996 (1587-88 CE) and is buried in a tomb in Istanbul, a türbe of his own design, just to the north of the Süleymaniye Mosque, across a street named Mimar Sinan Caddesi in his honour. He was buried near the tombs of his greatest patrons: Sultan Süleyman I and Sultana Haseki Hürrem, Suleiman's wife. Above the iron-grilled prayer window of his tomb is an epitaph written in Ottoman Turkish by the poet Mustafa Sai. It gives the year of his death and records that Sinan built 400 masjids (small mosques), 80 Friday mosques and the Kanuni Sultan Suleiman bridge at Büyükçekmece.[45]

In 1935, his remains were exhumed by a group of Turkish scholars. Proponents of the racial science popular at the time, they claimed that measurements of Sinan's skull proved that he was actually Turkish.[46]

His name is also given to:

- a crater on the planet Mercury.

- A Turkish state university, the Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts in Istanbul.

Sinan's portrait was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 10,000 lira banknotes of 1982-1995[47] and a 7 500 000 lira coin of 2001 (in the "millennium" series), also on 6 postage stamps: 100 lira 1957 (400th anniversary of the opening of the Suleymaniye Mosque), 50 lira 1988 (400th anniversary of Sinan's death) and a set of 4 issued on 14 November 2007 (60, 70, 70 & 80 Kurus - Sinan and his works).

Elif Shafak's novel The Architect's Apprentice revolves around Mimar Sinan: "Filled with the scents, sounds and sights of the Ottoman Empire, when Istanbul was the teeming centre of civilisation, The Architect's Apprentice is a magical, sweeping tale of one boy and his elephant caught up in a world of wonder and danger."[48]

See also

Notes

- Goodwin (2001), p. 87

- Kinross (1977), pp 214–215

- De Osa, Veronica.

- Saoud (2007), p. 7

- Vasari (1963), Book IV, p. 122

- http://home.howstuffworks.com/home-improvement/construction/planning/10-most-famous-architects2.htm

- Encyclopædia Britannica. Sinan (Ottoman architect):

Sinan, also called Mimar Sinan (“Architect Sinan”) or Mimar Koca Sinan (“Great Architect Sinan”) (born c. 1490, Ağırnaz, Turkey—died July 17, 1588, Constantinople [now Istanbul]), most celebrated of all Ottoman architects, whose ideas, perfected in the construction of mosques and other buildings, served as the basic themes for virtually all later Turkish religious and civic architecture.

The son of Greek or Armenian Christian parents, Sinan entered his father’s trade as a stone mason and carpenter. - Günay, Reha (2006). A guide to the works of Sinan the architect in Istanbul. Istanbul, Turkey: Yapı-Endüstri Merkezi Yayınları. p. 23. ISBN 975-8599-77-1. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- Fletcher, Richard (2005). The cross and the crescent: Christianity and Islam from Muhammad to the Reformation (Reprinted. ed.). London: Penguin. p. 138. ISBN 9780670032716.

...was Sinan the Old-he lived to be about ninety-an Armenian from Anatolia who had been brought to the capital as one of the 'gathered'.

- Zaryan, Sinan, Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, p. 385.

- Kouymjian, Dickran. "Armenia from the Fall of the Cilician Kingdom (1375) to the Forced Emigration under Shah Abbas (1604)" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, p. 13. ISBN 0-312-10168-6.

- Alboyajian (1937), vol. 2, pp. 1533-34.

- Jackson, Thomas Graham (1913). Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 143.

They are many of them designed by Sinan, who is said to have been an Armenian

- Sitwell, Sacheverell (1939). Old Fashioned Flowers. Country Life. p. 74.

The architect Sinan, perhaps of Armenian descent, raised mosques and other buildings all over the Turkish Empire.

- Talbot, Hamlin Architecture Through the Ages. University of Michigan, p. 208.

- Byzantium and the Magyars, Gyula Moravcsik, Samuel R. Rosenbaum p.28.

- Kathleen Kuiper. Islamic Art, Literature, and Culture. — The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009 — p. 204 — ISBN 9781615300976: "The son of Greek Orthodox parents, Sinan entered his father's trade as a stone mason and carpenter." .

- Sinan: the grand old master of Ottoman architecture, p. 35, Aptullah Kuran, Institute of Turkish Studies, 1987

- Walker, Benjamin and Peter Owen Foundations of Islam: the making of a world faith, 1998, p. 275.

- Goodwin 2003, p. 199.

- Rogers, J. M. (2006). Sinan: Makers of Islamic Civilization. I.B.Tauris: Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. p. backcover. ISBN 978-1-84511-096-3.

(Sinan) He was born in Cappadocia, probably into a Greek Christian family. Drafted into the Janissaries during his adolescence, he rapidly gained promotion and distinction as a military engineer.

- Cragg, Kenneth (1991). The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-664-22182-3.

- al-Lubnānī lil-Dirāsāt, Markaz (1992). The Beirut review, Issue 3. Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. p. 113. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- Brown, Percy (1942). Indian architecture: (The Islamic period). Taraporevala Sons. p. 94.

… the fame of the leading Ottoman architect, Sinan, having reached his ears, he is reported to have invited certain pupils of this Albanian genius to India to carry out his architectural schemes.

- Akgündüz Ahmed & Öztürk Said, (2011), Ottoman History, Misperfections and Truths, IUR Press (Islamitische Universiteit Rotterdam), Pg.196, See online. Quoted from the book: "According to yet another view, Sinan came from a Christian Turkish family, whose father's name was Abdulmennan and his grandfather's Doğan Yusuf."

- Goodwin 2003, pp. 199-200.

- This decree was published in the Turkish journal Türk Tarihi Encümeni Mecmuası, vol. 1, no. 5 (June 1930-May 1931) p. 10.

- Necipoğlu 2007, p. 147.

- Constantinople, de Byzance à Stamboul, Celâl Esad Arseven, H. Laurens, 1909

- Muller, Herbert Joseph (1961). The Loom of History. New American Library. p. 439.

- "Architects, Craftsmen, Weavers: Armenians and Ottoman Art". Abstracts from the International Conference ARMENIAN CONSTANTINOPLE organized by Richard G. Hovannisian, UCLA, May 19–20, 2001. Social Sciences Division University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Brown, Percy (1942). Indian architecture: (The Islamic period). Taraporevala Sons. p. 92. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

… the fame of the leading Ottoman architect, Sinan, having reached his ears, he is reported to have invited certain pupils of this Albanian genius to India to carry out his architectural schemes.

- Mahajan, Vidya Dhar; Savitri Mahajan (1962). The Muslim rule in India, Volume 1. S.Chand. p. 210. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Sinan (Ottoman architect)

- Kinross, pp 214–215.

- Sinan (in Dictionary of Islamic Architecture) Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- A list of the buildings designed by Mimar Sinan

- The Drina Bridge gave its name to the famous novel "Na Drini ćuprija" by the Yugoslav author Ivo Andrić.

- Tracy, James D.; Savitri Mahajan (2000). City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- (Article’s author): Gjergji Frashëri (2000). Fjalori Enciklopedik Shqiptar. Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. p. 2946. ISBN 978-99956-10-32-6.

- Albanian Cultural Heritage (PDF). Republic of Albania, National Tourism Agency. 2000. p. 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- Harmancioglu, Nilgun B.; Altinbilek, Dogan (2019-06-04). Water Resources of Turkey. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-030-11729-0.

- William J. Hennessey, PhD, Director, Univ. of Michigan Museum of Art. IBM 1999 WORLD BOOK.

- Marvin Trachtenberg and Isabelle Hyman. Architecture: from Prehistory to Post-Modernism. p. 223.

- Necipoĝlu 2005, p. 147.

- Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü (2013). Atatürk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780691157948.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group - Ten Thousand Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, II. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, III. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine & IV. Series Archived 2009-07-29 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- Elif Shafak (6 November 2014). "The Architect's Apprentice by Elif Shafak - Waterstones.com". waterstones.com.

Sources

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2003) [1971]. A History of Ottoman Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27429-3.

- Necipoĝlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-244-7.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2007). "Creation of a national genius: Sinan and the historiography of "classical" Ottoman architecture". Muqarnas. 24: 141–183. JSTOR 25482458.

Further reading

- (in Armenian) Alboyajian, Arshag A. Պատմութիին հայ Կեսարիոյ (History of Armenian Kayseri). 2 vols. Cairo: H. Papazian, 1937.

- (in Turkish) Çelebi, Sai Mustafa (2004). Book of Buildings : Tezkiretü'l Bünyan Ve Tezkiretü'l-Ebniye (Memoirs of Sinan the Architect). Koç Kültür Sanat Tanıtım ISBN 975-296-017-0

- Crane, Howard; Akın, Esra; Necipoĝlu, Gülru, eds. (2006). Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-century Texts. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14168-1.

- De Osa, Veronica (1982). Sinan the Turkish Michelangelo. New York: Vantage Press ISBN 0-533-04655-6

- (in German) Egli, Ernst (1954). Sinan, der Baumeister osmanischer Glanzzeit, Erlenbach-Zürich, Verlag für Architektur; ISBN 1-904772-26-9

- Egli, Hans G. (1997). Sinan: An Interpretation. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. ISBN 978-9758070121.

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2001). The Janissaries. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-055-2

- Güler, Ara; Burelli, Augusto Romano; Freely, John (1992). Sinan: Architect of Suleyman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Golden Age. WW Norton & Co. Inc. ISBN 0-500-34120-6

- Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire London: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8

- Kuran, Aptullah. (1987). Sinan: The Grand Old Master of Ottoman architecture, Ada Press Publishers. ISBN 0-941469-00-X

- (in Turkish) Kuran, Aptullah; Ara Güler (Illustrator); Mustafa Niksarli (Illustrator). (1986) Mimar Sinan. Istanbul: Hürriyet Vakfi. ISBN 3-89122-007-3

- Rogers, J M. (2005). Sinan. I.B. Tauris ISBN 1-84511-096-X

- Saoud, Rabat (2007). Sinan: The Great Ottoman Architect and Urban Designer. Manchester: Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation.

- Sewell, Brian. (1992) Sinan: A Forgotten Renaissance Cornucopia, Issue 3, Volume 1. ISSN 1301-8175

- Stratton, Arthur (1972). Sinan. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-02901-1.

- Turner, J. (1996). Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, USA; New Ed edition; ISBN 0-19-517068-7

- Van Vynckt, Randall J. (editor). (1993) International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture Volume 1. Detroit: St James Press. ISBN 1-55862-089-3

- Vasari, G. (1963). The Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects. (Four volumes) Trans: A.B. Hinds, Editor: William Gaunt. London and New York: Everyman.

- Wilkins, David G. Synan in Van Vynckt (1993), p. 826.

- A Guide to Ottoman Bulgaria" by Dimana Trankova, Anthony Georgieff and Professor Hristo Matanov; published by Vagabond Media, Sofia, 2011

- Tertiary Sources

- (in Armenian) Zaryan, Armen. «Սինան» (Sinan). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. x. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1984, pp. 385–386.

See also

- (in French) Roux, Jean-Paul (1988). "Les Mosquées de Sinan", Les Dossiers d'archéologie, May 1988, number 127.

- (in French) Stierlin, Henri (1988). "Sinan et Soliman le Magnifique", Les Dossiers d'archéologie, May 1988, number 127.

- (in French) Topçu, Ali (1988a) "Sinan et l'architecture civile", Les Dossiers d'archéologie, May 1988, number 127.

- (in French) Topçu, Ali (1988b)."Sinan et la modernité", Les Dossiers d'archéologie, May 1988, number 127.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mimar Sinan. |

- Mimar Sinan founder of this Foundation - with a picture of his last will and proof of his original name (in Turkish)

- Pictures of the city of Edirne, with many pictures of the Selimiye Mosque

- Pictures of some 30 mosques by Sinan in Istanbul

- A map and a short guide for Sinan's works in Istanbul (in Turkish)

- Photos of some Sinan mosques in Istanbul

- Map of some Sinan mosques in Istanbul

- Master Builder of the 16th Century Ottoman Mosque

- Mimar Sinan Bridge in Büyükçekmece

- The Ottoman architect who linked East and West

- Peerless Turkish architect claimed to be headless in tomb

- Mimar Sinan's life and works (in Turkish)

.jpg.webp)