Model (person)

A model is a person with a role either to promote, display or advertise commercial products (notably fashion clothing in fashion shows) or to serve as a visual aid for people who are creating works of art or to pose for photography. Though models are predominantly female, there are also male models, especially to model clothing. Models may work professionally or casually.

Modelling ("modeling" in American English) is considered to be different from other types of public performance, such as acting or dancing. Although the difference between modelling and performing is not always clear, appearing in a film or a play is not generally considered to be "modelling". Similarly, appearing in a TV advertisement is generally not considered modelling. Modelling generally does not involve speaking. Personal opinions are generally not expressed and a model's reputation and image are considered critical.

Types of modelling include: fashion, glamour, fitness, bikini, fine art, body-part, promotional and commercial print models. Models are featured in a variety of media formats including: books, magazines, films, newspapers, internet and television. Fashion modelling as a profession is sometimes featured in films (Prêt-à-Porter and Looker), reality TV shows (America's Next Top Model and The Janice Dickinson Modeling Agency) and music videos ("Freedom! '90", "Wicked Game", "Daughters" and "Blurred Lines").

Celebrities, including actors, singers, sports personalities and reality TV stars, frequently participate in modelling contests, assignments as well as contracts in addition to their regular work. Often, modelling is not a full-time, main activity.

History

Early years

Modelling as a profession was first established in 1853 by Charles Frederick Worth, the "father of haute couture", when he asked his wife, Marie Vernet Worth, to model the clothes he designed.[1][2] The term "house model" was coined to describe this type of work. Eventually, this became common practice for Parisian fashion houses. There were no standard physical measurement requirements for a model, and most designers would use women of varying sizes to demonstrate variety in their designs.

With the development of fashion photography, the modelling profession expanded to photo modelling. Models remained fairly anonymous, and relatively poorly paid, until the late 1940s, when the world's first three supermodels, Barbara Goalen, Bettina Graziani and Lisa Fonssagrives began commanding very large sums. During the 1940s and 1950s, Graziani was the most photographed woman in France and the undisputed queen of couture, while Fonssagrives appeared on over 200 Vogue covers; her name recognition led to the importance of Vogue in shaping the careers of fashion models. One of the most popular models during the 1940s was Jinx Falkenburg who was paid $25 per hour, a large sum at the time;[3] through the 1950s, Wilhelmina Cooper, Jean Patchett, Dovima, Dorian Leigh, Suzy Parker, Evelyn Tripp and Carmen Dell'Orefice also dominated fashion.[4] Dorothea Church was among the first black models in the industry to gain recognition in Paris. However, these models were unknown outside the fashion community. Wilhelmina Cooper's measurements were 38"-24"-36" whereas Chanel Iman's measurements are 32"-23"-33".[5] In 1946, Ford Models was established by Eileen and Gerard Ford in New York, making it one of the oldest model agencies in the world.

The 1960s and the beginning of the industry

In the 1960s, the modelling world began to establish modelling agencies. Throughout Europe, secretarial services acted as models' agents charging them weekly rates for their messages and bookings. For the most part, models were responsible for their own billing. In Germany, agents were not allowed to work for a percentage of a person's earnings, so referred to themselves as secretaries. With the exception of a few models travelling to Paris or New York, travelling was relatively unheard of for a model. Most models only worked in one market due to different labor laws governing modelling in various countries. In the 1960s, Italy had many fashion houses and fashion magazines but was in dire need of models. Italian agencies would often coerce models to return to Italy without work visas by withholding their pay.[6] They would also pay their models in cash, which models would have to hide from customs agents. It was not uncommon for models staying in hotels such as La Louisiana in Paris or the Arena in Milan to have their hotel rooms raided by the police looking for their work visas. It was rumoured that competing agencies were behind the raids. This led many agencies to form worldwide chains; for example, the Marilyn Agency has branches in Paris and New York.[6]

By the late 1960s, London was considered the best market in Europe due to its more organised and innovative approach to modelling. It was during this period that models began to become household names. Models such as Jean Shrimpton, Tania Mallet, Celia Hammond, Twiggy, Penelope Tree, and dominated the London fashion scene and were well paid, unlike their predecessors.[7] Twiggy became The Face of '66 at the age of 16.[8] At this time, model agencies were not as restrictive about the models they represented, although it was uncommon for them to sign shorter models. Twiggy, who stood at 5 feet 6 inches (168 cm) with a 32" bust and had a boy's haircut, is credited with changing model ideals. At that time, she earned £80 an hour, while the average wage was £15 a week.

.jpg.webp)

In 1967, seven of the top model agents in London formed the Association of London Model Agents. The formation of this association helped legitimize modelling and changed the fashion industry. Even with a more professional attitude towards modelling, models were still expected to have their hair and makeup done before they arrived at a shoot. Meanwhile, agencies took responsibility for a model's promotional materials and branding. That same year, former top fashion model Wilhelmina Cooper opened up her own fashion agency with her husband called Wilhelmina Models. By 1968, FM Agency and Models 1 were established and represented models in a similar way that agencies do today.[9][10] By the late 1960s, models were treated better and were making better wages. One of the innovators, Ford Models, was the first agency to advance models money they were owed and would often allow teen models, who did not live locally, to reside in their house, a precursor to model housing.

The 1970s and 1980s

The innovations of the 1960s flowed into the 1970s fashion scene. As a result of model industry associations and standards,[11] model agencies became more business minded, and more thought went into a model's promotional materials. By this time, agencies were starting to pay for a model's publicity.[6] In the early 1970s, Scandinavia had many tall, leggy, blonde-haired, blue-eyed models and not enough clients. It was during this time that Ford Models pioneered scouting.[6] They would spend time working with agencies holding modelling contests. This was the precursor to the Ford Models Supermodel of the World competition which was established in 1980. Ford also focused their attentions on Brazil which had a wide array of seemingly "exotic" models, which eventually led to establishment of Ford Models Brazil. It was also during this time that the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue debuted. The magazine set a trend by photographing "bigger and healthier" California models,[12] and printing their names by their photos, thus turning many of them into household names and establishing the issue as a hallmark of supermodel status.[12]

The 1970s marked numerous milestones in fashion. Beverly Johnson was the first black woman to appear on the cover of U.S. Vogue in 1974.[13] Models, including Iman, Grace Jones, Pat Cleveland, Alva Chinn, Donyale Luna, Minah Bird, Naomi Sims, and Toukie Smith were some of the top black fashion models who paved the way for black women in fashion. In 1975, Margaux Hemingway landed a then-unprecedented million-dollar contract as the face of Fabergé's Babe perfume and the same year appeared on the cover of Time magazine, labelled one of the "New Beauties", giving further name recognition to fashion models.[14]

Many of the world's most prominent modelling agencies were established in the 1970s and early 1980s. These agencies created the standard by which agencies now run. In 1974, Nevs Models was established in London with only a men's board, the first of its kind. Elite Models was founded in Paris in 1975 as well as Friday's Models in Japan.[15][16] The next year Cal-Carries was established in Singapore, the first of a chain of agencies in Asia. In 1977, Select Model Management opened its doors as well as Why Not Models in Milan. By the 1980s, agencies such as Premier Model Management, Storm Models, Mikas, Marilyn, and Metropolitan Models had been established.

In October 1981, Life cited Shelley Hack, Lauren Hutton and Iman for Revlon, Margaux Hemingway for Fabergé, Karen Graham for Estée Lauder, Christina Ferrare for Max Factor, and Cheryl Tiegs for CoverGirl by proclaiming them the "million dollar faces" of the beauty industry. These models negotiated previously unheard of lucrative and exclusive deals with giant cosmetics companies, were instantly recognizable, and their names became well known to the public.[17]

By the 1980s, most models were able to make modelling a full-time career. It was common for models to travel abroad and work throughout Europe. As modelling became global, numerous agencies began to think globally. In 1980, Ford Models, the innovator of scouting, introduced the Ford Models Supermodel of the World contest.[18] That same year, John Casablancas opened Elite Models in New York. In 1981, cosmetics companies began contracting top models to lucrative endorsement deals. By 1983, Elite developed its own contest titled the Elite Model Look competition. In New York during the 1980s there were so-called "model wars" in which the Ford and Elite agencies fought over models and campaigns. Models were jumping back and forth between agencies such Elite, Wilhelmina, and Ford.[19] In New York, the late 1980s trend was the boyish look in which models had short cropped hair and looked androgynous. In Europe, the trend was the exact opposite. During this time, a lot of American models who were considered more feminine looking moved abroad.[20] By the mid-1980s, big hair was made popular by some musical groups, and the boyish look was out. The curvaceous models who had been popular in the 1950s and early 1970s were in style again. Models like Patti Hansen earned $200 an hour for print and $2,000 for television plus residuals.[21] It was estimated that Hansen earned about $300,000 a year during the 1980s.

1990s

The early 1990s were dominated by the high fashion models of the late 1980s. In 1990, Linda Evangelista famously said to Vogue, "we don't wake up for less than $10,000 a day". Evangelista and her contemporaries, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington, Tatjana Patitz and Stephanie Seymour, became arguably the most recognizable models in the world, earning the moniker of "supermodel", and were boosted to global recognition and new heights of wealth for the industry.[22] In 1991, Turlington signed a contract with Maybelline that paid her $800,000 for twelve days' work each year.

By the mid‑1990s, the new "heroin chic" movement became popular amongst New York and London editorial clients. Kate Moss became its poster child through her ads for Calvin Klein. In spite of the heroin chic movement, model Claudia Schiffer earned $12 million. With the popularity of lingerie retailer Victoria's Secret, and the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, there was a need for healthier-looking supermodels such as Tyra Banks and Heidi Klum to meet commercial modelling demand. The mid‑1990s also saw many Asian countries establishing modelling agencies.

By the late 1990s, the heroin chic era had run its course. Teen-inspired clothing infiltrated mainstream fashion, teen pop music was on the rise, and artists such as Britney Spears, Aaliyah and Christina Aguilera popularized pleather and bare midriffs. As fashion changed to a more youthful demographic, the models who rose to fame had to be sexier for the digital age. Following Gisele Bundchen's breakthrough, a wave of Brazilian models including Adriana Lima and Alessandra Ambrosio rose to fame on runways and became popular in commercial modelling throughout the 2000s. Some have tied this increase in Brazilian models to the trend of magazines featuring celebrities instead of models on their covers.[23]

2000s and after

In the late 2000s, the Brazilians fell out of favour on the runways. Editorial clients were favouring models with a china-doll or alien look to them, such as Gemma Ward and Lily Cole. During the 2000s, Ford Models and NEXT Model Management were engaged in a legal battle, with each agency alleging that the other was stealing its models.[24]

However, the biggest controversy of the 2000s was the health of high-fashion models participating in fashion week. While the health of models had been a concern since the 1970s, there were several high-profile news stories surrounding the deaths of young fashion models due to eating disorders and drug abuse. The British Fashion Council subsequently asked designers to sign a contract stating they would not use models under the age of sixteen.[25] On March 3, 2012, Vogue banned models under the age of sixteen as well as models who appeared to have an eating disorder.[26] Similarly, other countries placed bans on unhealthy, and underage models, including Spain, Italy, and Israel, which all enacted a minimum body mass index (BMI) requirement.

In 2013, New York toughened its child labor law protections for models under the age of eighteen by passing New York Senate Bill No. 5486, which gives underage models the same labor protections afforded to child actors. Key new protections included the following: underage models are not to work before 5:00 pm or after 10:00 pm on school nights, nor were they to work later than 12:30 am on non-school nights; the models may not return to work less than twelve hours after they leave; a pediatric nurse must be on site; models under sixteen must be accompanied by an adult chaperone; parents or guardians of underage models must create a trust fund account into which employers will transfer a minimum of 15% of the child model's gross earnings; and employers must set aside time and a dedicated space for educational instruction.[27]

Types

Fashion modelling

Runway modelling

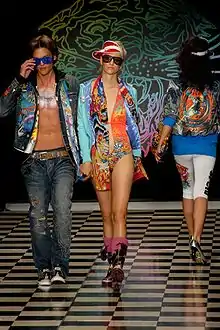

Runway models showcase clothes from fashion designers, fashion media, and consumers. They are also called "live models" and are self-employed. They are wanted to be over the height of 5'11" for men and 5'8" for women. Runway models work in different locations, constantly travelling between those cities where fashion is well known—New York City, London, Paris, and Milan. Second-tier international fashion center cities include Rome, Florence, Venice, Brescia, Barcelona, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Moscow.

The criteria for runway models include certain height and weight requirements. During runway shows, models have to constantly change clothes and makeup. Models walk, turn, and stand in order to demonstrate a garment's key features. Models also go to interviews (called "go and sees") to present their portfolios.[28] The more experience a model has, the more likely she/he is to be hired for a fashion show. A runway model can also work in other areas, such as department store fashion shows, and the most successful models sometimes create their own product lines or go into acting.[29]:191–192

The British Association of Model Agents (AMA) says that female models should be around 34"-24"-34" and between 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) and 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) tall.[30] The average model is very slender. Those who do not meet the size requirement may try to become a plus-size model.[31] According to the New York Better Business Career Services website, the preferred dimensions for a male model are a height of 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) to 6 ft 2 in (188 cm), a waist of 29–32 in (73.66–81.28 cm) and a chest measurement of 39–40 in (99.06–101.60 cm).[32] Male runway models are notably skinny and well toned.[33]

Male and female models must also possess clear skin, healthy hair, and attractive facial features. Stringent weight and body proportion guidelines form the selection criteria by which established, and would‑be, models are judged for their placement suitability, on an ongoing basis. There can be some variation regionally, and by market tier, subject to current prevailing trends at any point, in any era, by agents, agencies and end-clients.

Formerly, the required measurements for models were 35"-23.5"-35" in (90-60-90 cm), the alleged measurements of Marilyn Monroe. Today's fashion models tend to have measurements closer to the AMA-recommended shape, but some – such as Afghan model Zohre Esmaeli – still have 35"-23.5"-35" measurements. Although in some fashion centres, a size 00 is more desirable than a size 0.

The often thin shape of many fashion models has been criticized for warping girls' body image and encouraging eating disorders.[34] Organisers of a fashion show in Madrid in September 2006 turned away models who were judged to be underweight by medical personnel who were on hand.[35] In February 2007, following the death of her sister, Luisel Ramos, also a model, Uruguayan model Eliana Ramos became the third fashion model to die of malnutrition in six months. The second victim was Ana Carolina Reston.[36] Luisel Ramos died of heart failure caused by anorexia nervosa just after stepping off the catwalk. In 2015, France passed a law requiring models to be declared healthy by a doctor in order to participate in fashion shows. The law also requires re-touched images to be marked as such in magazines.[37]

Plus-size

Plus-size models are models who generally have larger measurements than editorial fashion models. The primary use of plus-size models is to appear in advertising and runway shows for plus-size labels. Plus-size models are also engaged in work that is not strictly related to selling large-sized clothing, e.g., stock photography and advertising photography for cosmetics, household and pharmaceutical products and sunglasses, footwear and watches. Therefore, plus-size models do not exclusively wear garments marketed as plus-size clothing. This is especially true when participating in fashion editorials for mainstream fashion magazines. Some plus-size models have appeared in runway shows and campaigns for mainstream retailers and designers such as Gucci, Guess, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Levi's and Versace Jeans.[38][39][40][41]

Normal-size

Also known as the "in-between" and "middle models",[42] they are neither considered catalogue size (0–2) nor plus-size (10 up).[43] Actress Mindy Kaling has described this body type in her 2011 book Is Everybody Hanging Out Without Me? writing, "Since I am not model-skinny, but also not super-fat... I fall into that nebulous, 'Normal American Woman Size' that legions of fashion stylists detest... Many stylists hate that size because, I think, to them, I lack the self-discipline to be an aesthetic, or the sassy confidence to be a total fatty hedonist. They're like, 'Pick a lane.'"[44] There is criticism that these models have been left out of the conversation because fashion companies and brands opt to employ the extremes of the spectrum.[45][46]

Model Camille Kostek who was on a solo cover of Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue in 2019 has stated that she was told by a well-known international modeling agency "...that it was too bad that I wasn’t a size 10. That plus size is a big market right now and it’s too bad I wasn’t measuring bigger. My size (4/6) is considered an "in-between size," meaning I'm not a straight model nor plus model, I'm right in the middle.[47][48]

Magazine modeling

Fashion modeling also includes modeling clothing in fashion magazines. In Japan, there are different types of fashion magazine models. Exclusive models (専属モデル, senzoku moderu) are models who regularly appear in a fashion magazine and model exclusively for it.[49] On the other hand, street models, or "reader models" (読者モデル, dokusha moderu, abbreviated as "dokumo" for short), are amateur models who model part-time for fashion magazines in conjunction to school work and their main jobs.[49][50][51] Unlike professional models, street models are meant to represent the average person in appearance and do not appear on runways.[50] Street models are also not exclusively contracted to fashion magazines.[49] If a street model is popular enough, some of them become exclusive models.[49] Many fashion icons and musicians in Japan began their career as street models, including Kaela Kimura and Kyary Pamyu Pamyu.[50]

Black models

The arrival of black women modeling as a profession began in early postwar America. It began most notably from the need of advertisers and a rise of black photography magazines. The women who advanced in such careers were those in a middle-class system that emphasized the conservative value of marriage, motherhood, and domesticity. Originally titled the "Brownskin" model, black women refined the social, sexual, and racial realities confined in the gender expectations of the modeling world. There was a profound need for black women to partake in the advertising process for the new "Negro Market".[52] With the help of Branford Models, the first black agency, 1946 was the beginning of the black modeling era. Branford Models’ was able to "overturn the barriers facing African American in the early postwar period" especially by lifting at least one economic freedom.[52] In this postwar America, the demand for such presence in magazines advanced "as a stage for models to display consumer goods" while assisting "in constructing a new visual discourse of urban middle-class African America".[52]

While they represented diversity, a major gap in the fashion industry, it was only until the 1970s that black models had a substantial presence in the modeling world. Known as the "Black is Beautiful" movement, the 1970s became the era of the black model. With growing disenfranchisement and racial in-equality, the United States recognized the urgency of opening the "doors of social access and visibility to black Americans".[53] The world of fashion was the gateway for social change. "The world of fashion was similarly looked to as a place where the culture could find signs of racial progress. Expressions of beauty and glamour mattered. Good race relations required taking note of who was selling women lipsticks and mini skirts, which meant that advertisers began looking for black models"[53] Black models were looked to as the vehicle of social change. They were given the opportunity to balance out the lack of presence of black individuals in the mainstream culture. Agencies were beginning to scout black models and focus on the social change they were contributing too. Life Magazine in October 1969, covered their issue with Naomi Sims, one of the most influential black models in the industry. Her rise to fame led her to international magazine jobs and individual projects with designers across the globe.[54] In the Life Magazine issue, Black Beauty, a new agency that represented black models, had a spread in the magazine that showcased 39 black models. Each one of the models had their own unique features, allowing black expression to progress through this historic magazine spread.[53]

With the movement's presence both in magazines and the runway, designers began to realize the need to include black models on their runways and advertisements. The battle of Versallies was one of the most notable moments in fashion history that put black models on the map. Eleanor Lambert, creator of Fashion Week and a major "[controller] of the narrative of American fashion", set up a dinner and a fundraiser to both increase American fashion visibility and restore the palace of Versailles.[53] Five French designers and five American designers battled it out on the runway, showing off the fashion, and for the Americans, black models as well. Oscar de la Renta stated "it was the black models that had made the difference." Pat Cleveland, Bethann Hardiason, Billie Blair, Jennifer Brice, Alva Chinn, and Ramona Saunders, were among the many black models that helped Team America win and stun the French competition. This competition made the black model a worldwide phenomenon. The French were beginning to welcome diversity on the runway and in their advertising. With the recognition Versaillies had given, black presence in the modeling world carried out into the 1980s and the 1990s. The models were now known by name and the publicity that came with the designers they were modeling for. With the rise of the supermodel, models like Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks paved the way for black success.[53] Naomi Campbell, born in London, was the first black model to cover American Vogue, TIME magazine, Russian Vogue, and the first British black model to cover British vogue. Brands like Chanel, Louis Vitton, Balmain, Prada, and more have all featured Campbell in their campaigns. She used her remarkable success to achieve more than fashion excelience.

By the mid-1990s, black presence in the modeling world had dramatically decreased. Designers began to favor a consistent aesthetic and elected for skinnier white models. This reality was paved by models such as Kate Moss and Stella Tennant who provided a more consistent look for the runway. At this time, "the number of working black models in high-profile runway presentation... became so dire that stories began appearing in the mainstream media about the whitewashing of the runway".[55] In response, models like Campbell, Iman, and Bethann Hardison, joined forces throughout the"Diversity Coalition" in an attempt to "call out and accuse prominent fashion houses for snubbing Black and Asian models on the catwalk, editorial spreads, and campaigns".[53] The lack of representation was, in part, due to the belief that "black girls don’t push products", which "encouraged people who work directly and indirectly in the industry to speak out on the injustices that go on within it".[53] In the 1990s, it was quite clear that the top designers simply preferred a new aesthetic that excluded models of color, which resulted in only 6% of runway models to be women of color.[53] Campbell's Diversity Coalition's main mission was to "expedite inclusion on the runway by deliberately calling out designers who have executed acts of racism on the runway".[53] According to Campbell, it was their choice to not include black models on the runway and desire a uniformed runway that resulted in a racist act. Although such a dramatic effort to exclude black presence from the fashion world, models like Tyra Banks and Veronica Webb persisted. Banks not only dominated the runway as a teen, she took over countless pop culture platforms. Being the first black model to cover Sports Illustrated, Banks was one of the most prominent models in the early 2000s. Covering Sports Illustrated, Elle, Essence, Vogue, and walking for Chanel, Chrisitan Dior, and Claude Motnanta, Banks was truly dominating the fashion world. In addition, she acted in Fresh Prince of Bel Air and created her own reality competition show called America's Next Top Model.[54] In conversation with Trebay of Los the New York Times, Banks stated that her first cover on Sport Illustrated "changed [her] life overnight.. You have to think back to remember what that did for an appreciation of black beauty to have a black girl, a girl next door type, on the cover of one of the most mass mainstream magazines of our lives. It was a societal statement, a political statement, and an economic one".[56] Now, models like Joan Smalls, Winne Harlow, Slick Woods, Jasmine Sanders and more are continuing the fight for black presence in the modeling world and using their successors as inspiration.

Fit models

A fit model (sometimes fitting model) is a person who is used by a fashion designer or clothing manufacturer to check the fit, drape and visual appearance of a design on a 'real' human being, effectively acting as a live mannequin.[57]

Glamour models

Glamour modelling focuses on sexuality and thus general requirements are often unclear, being dependent more on each individual case. Glamour models can be any size or shape. There is no industry standard for glamour modelling and it varies greatly by country. For the most part, glamour models are limited to modelling in calendars, men's magazines, such as Playboy, bikini modelling, lingerie modelling, fetish modelling, music videos, and extra work in films. However, some extremely popular glamour models transition into commercial print modelling, appearing in swimwear, bikini and lingerie campaigns.

It is widely considered that England created the market for glamour modelling when The Sun established Page 3 in 1969,[58] a section in their newspaper which featured sexually suggestive images of Penthouse and Playboy models. From 1970 models appeared topless. In the 1980s, The Sun's competitors followed suit and produced their own Page 3 sections.[58] It was during this time that glamour models first came to prominence with the likes of Samantha Fox. As a result, the United Kingdom has a very large glamour market and has numerous glamour modelling agencies to this day.

It was not until the 1990s that modern glamour modelling was established. During this time, the fashion industry was promoting models with waif bodies and androgynous looking women, which left a void. Several fashion models, who were deemed too commercial, and too curvaceous, were frustrated with industry standards, and took a different approach. Models such as Victoria Silvstedt left the fashion world and began modelling for men's magazines.[59] In the previous decades, posing nude for Playboy resulted in models losing their agencies and endorsements.[60] Playboy was a stepping stone which catapulted the careers of Victoria Silvstedt, Pamela Anderson, and Anna Nicole Smith. Pamela Anderson became so popular from her Playboy spreads that she was able to land roles on Home Improvement and Baywatch.

In the mid-1990s, a series of men's magazines were established such as Maxim, FHM, and Stuff. At the same time, magazines including Sweden's Slitz (formerly a music magazine) re-branded themselves as men's magazines. Pre-internet, these magazines were popular among men in their late teens and early twenties because they were considered to be more tasteful than their predecessors. With the glamour market growing, fashion moved away from the waifs and onto Brazilian bombshells. The glamour market, which consisted mostly of commercial fashion models and commercial print models, became its own genre due to its popularity. Even in a large market like the United Kingdom, however, glamour models are not usually signed exclusively to one agency as they can not rely financially on one agency to provide them with enough work. It was, and still is, a common practice for glamour models to partake in kiss-and-tell interviews about their dalliances with famous men. The notoriety of their alleged bed-hopping often propels their popularity and they are often promoted by their current or former fling.[61] With Page 3 models becoming fixtures in the British tabloids, glamour models such as Jordan, now known as Katie Price, became household names. By 2004, Page 3 regulars earned anywhere from £30,000 to 40,000,[58] where the average salary of a non-Page 3 model, as of 2011, was between £10,000 and 20,000.[62] In the early 2000s, glamour models, and aspiring glamour models, appeared on reality television shows such as Big Brother to gain fame.[63] Several Big Brother alumni parlayed their fifteen minutes of fame into successful glamour modelling careers. However, the glamour market became saturated by the mid-2000s, and numerous men's magazines including Arena, Stuff and FHM in the United States went under.[64] During this time, there was a growing trend of glamour models, including Kellie Acreman and Lauren Pope, becoming DJs to supplement their income. In a 2012 interview, Keeley Hazell said that going topless is not the best way to achieve success and that "[she] was lucky to be in that 1% of people that get that, and become really successful."[65]

Alternative models

An alternative model is any model who does not fit into the conventional model types and may include punk, goth, fetish,[66] and tattooed[67] models or models with distinctive attributes. This type of modeling is usually a cross between glamour modeling and art modeling. Publishers such as Goliath Books in Germany introduced alternative models and punk photography to larger audiences. Billi Gordon, then known as Wilbert Anthony Gordon, was the top greeting card model in the world and inspired a cottage industry, including greeting cards, T-shirts, fans, stationery, gift bags, etc.[68]

Parts models

Some models are employed for their body parts. For example, hand models may be used to promote products held in the hand and nail-related products. (e.g. rings, other jewelry or nail polish). They are frequently part of television commercials.[69] Many parts models have exceptionally attractive body parts, but there is also demand for unattractive or unusual looking body parts for particular campaigns.

Hands are the most in-demand body parts. Feet models are also in high demand, particularly those who fit sample size shoes.[70] Models are also successful modelling other specific parts including abs, arms, back, bust or chest, legs, and lips.[71] Some petite models (females who are under 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) and do not qualify as fashion models) have found success in women's body part modelling.

Parts model divisions can be found at agencies worldwide. Several agencies solely represent parts models, including Hired Hands in London, Body Parts Models in Los Angeles, Carmen Hand Model Management in New York and Parts Models in New York.[72][73][74] Parts Models is the largest parts agency, representing over 300 parts models.[69][72][75][76][77]

Petite models

Petite models are models that are under the typical height requirements that are expected of fashion models. Petite models typically work more often in commercial, and print modeling (rather than runway modeling)

The height of models is typically above 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) for women, and above 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) for men. Models who are of heights such as 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) fall under the category of petite models.

Petite models typically model shoes because their feet are of more common sizes compared to the average fashion model.

Fitness models

Fitness modelling focuses on displaying a healthy, toned physique. Fitness models usually have defined muscle groups. The model's body weight is greater due to muscle weighing more than fat; however, they have a lower body fat percentage because the muscles are toned and sculpted. Fitness models are often used in magazine advertising; they can also in some cases be certified personal fitness trainers. However, other fitness models are also athletes and compete as professionals in fitness and figure competitions. There are several agencies in large markets such as New York, London, and Germany that have fitness modelling agencies. While there is a large market for these models, most of these agencies are a secondary agency promoting models who typically earn their primary income as commercial models. There are also magazines that gear towards specifically fitness modelling or getting fit and in shape.

Gravure idols

In Japan, a gravure idol (グラビアアイドル, gurabia aidoru), often abbreviated to gradol (グラドル, guradoru), is a female model who primarily models for magazines, especially men's magazines, photobooks or DVDs. "Gurabia" (グラビア) is a Wasei-eigo term derived from "rotogravure", which is a type of intaglio printing process that was once a staple of newspaper photo features. The rotogravure process is still used for commercial printing of magazines, postcards, and cardboard product packaging.[78]

Gravure idols appear in a wide range of photographic styles and genres. Their photos are largely aimed at male audiences with poses or activities intended to be provocative or suggestive, generally accentuated by an air of playfulness and innocence rather than aggressive sexuality. Although gravure idols may sometimes wear clothing that exposes most of their body, they seldom appear fully nude. Gravure idols may be as young as pre-teen age up to their early thirties. In addition to appearing in mainstream magazines, gravure idols often release their own professional photobooks and DVDs for their fans. Many popular female idols in Japan launched their careers by starting out as gravure idols.[78][79]

Commercial print and on-camera models

Commercial print models generally appear in print ads for non-fashion products, and in television commercials. Commercial print models can earn up to $250 an hour. Commercial print models are usually non-exclusive, and primarily work in one location.

There are several large fashion agencies that have commercial print divisions, including Ford Models in the United States.

Promotional models

A promotional model is a model hired to drive consumer demand for a product, service, brand, or concept by directly interacting with potential consumers. The vast majority of promotional models tend to be attractive in physical appearance. They serve to provide information about the product or service and make it appealing to consumers. While the length of interaction may be short, the promotional model delivers a live experience that reflects on the product or service he or she is representing. This form of marketing touches fewer consumers for the cost than traditional advertising media (such as print, radio, and television); however, the consumer's perception of a brand, product, service, or company is often more profoundly affected by a live person-to-person experience.

Marketing campaigns that make use of promotional models may take place in stores or shopping malls, at tradeshows, special promotional events, clubs, or even at outdoor public spaces. Promotional models may also be used as TV host/anchor for interviewing celebrities such as at film awards, sports events, etc. They are often held at high traffic locations to reach as many consumers as possible, or at venues at which a particular type of target consumer is expected to be present.

Spokesmodels

"Spokesmodel" is a term used for a model who is employed to be associated with a specific brand in advertisements. A spokesmodel may be a celebrity used only in advertisements (in contrast to a brand ambassador who is also expected to represent the company at various events), but more often the term refers to a model who is not a celebrity in their own right. A classic example of the spokesmodel are the models hired to be the Marlboro Man between 1954 and 1999.

Trade show models

Trade show models work a trade show floorspace or booth, and represent a company to attendees. Trade show models are typically not regular employees of the company, but are freelancers hired by the company renting the booth space. They are hired for several reasons: trade show models can make a company's booth more visibly distinguishable from the hundreds of other booths with which it competes for attendee attention. They are articulate and quickly learn and explain or disseminate information on the company and its product(s) and service(s). And they can assist a company in handling a large number of attendees which the company might otherwise not have enough employees to accommodate, possibly increasing the number of sales or leads resulting from participation in the show.

Atmosphere models

Atmosphere models are hired by the producers of themed events to enhance the atmosphere or ambience of their event. They are usually dressed in costumes exemplifying the theme of the event and are often placed strategically in various locations around the venue. It is common for event guests to have their picture taken with atmosphere models. For example, if someone is throwing a "Brazilian Day" celebration, they would hire models dressed in samba costumes and headdresses to stand or walk around the party.

Podium models

Podium models differ from runway models in that they don't walk down a runway, but rather just stand on an elevated platform. They resemble live mannequins placed in various places throughout an event. Attendees can walk up to the models and inspect and even feel the clothing. Podium Modeling is a practical alternative way of presenting a fashion show when space is too limited to have a full runway fashion show.

Art models

Art models pose for any visual artist as part of the creative process. Art models are often paid professionals who provide a reference or inspiration for a work of art that includes the human figure. The most common types of art created using models are figure drawing, figure painting, sculpture and photography, but almost any medium may be used. Although commercial motives dominate over aesthetics in illustration, its artwork commonly employs models. Models are most frequently employed for art classes or by informal groups of experienced artists that gather to share the expense of a model.

Instagram models

Instagram models have become popular due to the widespread use of social media. They are models who gain their success as a result of the large number of followers they have on Instagram and other social media. They should not be confused with established models such as Cara Delevingne and Gigi Hadid, who use Instagram to promote their traditional modelling careers,[80] although some models, such as Playboy model Lindsey Pelas, begin their modelling careers conventionally and subsequently become Instagram models. Some models use Instagram success to develop their careers, such as Rosie Roff who worked as a fashion model before being discovered via Instagram and gaining work as a ring girl in American boxing. In some cases, Instagram provides unsigned models with a platform to attract the attention of agencies and talent scouts.[81] American model Matthew Noszka entered the profession as a result of being discovered on Instagram by Wilhelmina Models.[80]

The Instagram model concept originated in the late 2000s, when the boyfriends of fashion bloggers such as Rumi Neely and Chiara Ferragni began photographing their girlfriends in various outfits.[82] Instagram models often attempt to become social media influencers and engage in influencer marketing,[81] promoting products such as fashion brands and detox teas.[82] High-profile influencers are able to earn thousands of US dollars for promoting commercial brands. When choosing whom to employ, brands have become less concerned with the number of followers an influencer has and more focussed on their engagement marketing strategy. Research indicates that 89 per cent of influencers use Instagram to promote themselves compared to 20 per cent using Twitter and 16 per cent using Facebook.[81]

Some Instagram models have gained high-profile modelling jobs and become celebrities.[83] Fitness model Jen Selter had become an Internet celebrity by 2014 with nearly 2 million Instagram followers, gaining professional sports management work[84] and modelling for Vanity Fair magazine.[85] Cosplayer and model Anna Faith had acquired over 250,000 Instagram followers by 2014, gaining success from her ability to impersonate the Disney character Elsa.[86][87] With Facebook's continuing decrease in post reach, Instagram has increasingly become the favorite platform for cosplayers.[88][89] American actress Caitlin O'Connor had almost 300,000 Instagram followers in 2016, earning most of her social media income from endorsing products on Instagram.[90] Australian personal trainer Kayla Itsines acquired five-and-a-half million Instagram followers allowing her to build a business in the fitness industry.[91] Brazilian model Claudia Alende had gained a following of 2.8 million people on Instagram by 2015 and developed a career as a lingerie model.[92] Plus-size models Iskra Lawrence and Tess Holliday have used Instagram to demonstrate their potential as models.[81] Yashika Aannand, an Indian teenage actress rose to prominence in the Tamil film industry after gaining popularity among the public as an Instagram model with over 145,000 followers on her account by 2017.[93]

Instagram model techniques and aesthetics have also been used in unconventional or parody profiles. Instagram model Lil Miquela has blurred the line between reality and social media, amassing more than 200,000 followers without it being revealed whether she is real or computer-generated.[94] Australian comedian Celeste Barber had acquired 1.8 million Instagram followers by 2017, parodying celebrity fashion photographs with real-life reenactments.[95] In 2016, French organization Addict Aide ran a campaign to raise awareness for alcohol abuse among young people in which a model posed as Louise Delage, a fictitious 25-year-old Parisian whose Instagram photos nearly always featured alcohol. The account amassed 65,000 followers in a month, after which a reveal video posted to it had over 160,000 views.[96]

Some reports[97] suggest that a number of Instagram models obtain extra income by covertly working as prostitutes. Websites accusing various models of this, often without reliable evidence, have increased in popularity recently, sometimes with the unintended effect of increasing their earnings.[98] However, false accusations on these sites can harm legitimate models' reputations, and some women in the industry consider them to be a way for men to exert power over women.[99]

See also

References

- "modelworker.com". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- Walker, Harriet (4 May 2009). "Fabulous faces of fashion: A century of modelling". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "fashion models 1940s, fashion modeling in 1940, Forties Fashion modeling agencies, first fashion modeling agency in New York, 1940s fashion models, John Powers modeling agency, girls of the John Roberts Powers modeling agency, Powers Girls Photographs, popular 1". Oldmagazinearticles.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Cathy Horyn (4 February 2002). "Jean Patchett, 75, a Model Who Helped Define the 50s". New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Chanel Iman – Fashion Model – Profile on FMD". Fashionmodeldirectory.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Peter Marlowe (January 2007). "A Brief History Of Modelling". The Peter Marlowe Model Composite Archives. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008.

- Armstrong, Lisa (20 January 2012). "David Bailey's favourite model Jean Shrimpton was the Shrimp who sparked the Sixties – Telegraph". London: Fashion.telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Twiggy – The Official Site". Twiggylawson.co.uk. 23 February 1966. Archived from the original on 11 February 2003. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Europe's Leading Model Agency". Models 1. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "FM Agency – London – Contact". Fmmodelagency.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Europe's Leading Model Agency". Models 1. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Curtis, Bryan (16 February 2005). "The Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue: An intellectual history". Slate. Washington Post. Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Joy Sewing Beverly Johnson's got the right attitude Archived 2009-08-26 at the Wayback Machine The Houston Chronicle, Retrieved 23 August 2009

- Fonseca, Nicholas (29 June 2001). "Entertainment Weekly: Papa's Little Girl". Ew.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- "About Us". Fridayfarm.net. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Elite Model Management India Pvt. Ltd". Elitemodelsindia.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Best–Selling Beauties, Life October 1981, page 120

- "Ford Models Supermodel of the World". Supermodeloftheworld.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2000. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Rayl, Salley. "The Fashion World Is Rocked by Model Wars, Part Two: the Ford Empire Strikes Back". People.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Like (6 July 2010). "Kitchen Table Conversation with Cindy Morris and Roxan Gould on Vimeo". Vimeo.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Clurman, Shirley (18 February 1980). "Who Is Patti Hansen? Just the Successor to Tiegs and Fawcett, or So Says Scavullo". People.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Citations:

- Harold Koda, Kohle Yohannan (2009). The Model As Muse: Embodying Fashion (First ed.). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-58839-312-8. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Callahan, Susannah (4 August 2013). "Super models class of 1990 back in vogue". New York Post (www.nypost.com). NYP HOLDINGS, INC. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- "Supermodel Status: A Brief History Of The Supermodel". Fashion Gone Rogue (www.fashiongonerogue.com). Fashion Gone Rogue. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Brown, Laura (23 March 2009). "Classic Lindbergh". Harper's Bazaar (www.harpersbazaar.com). Brant Publishing. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Death of the Supermodels by C. L. Johnson, Urban Models 21 October 2002 online retrieved 13 July 2006 Archived 15 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Model agency wars Next vs Ford (Vogue.com UK)". Vogue.co.uk. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Fashion news: Underage models banned at London Fashion Week". Marie Claire. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Vogue bans models who are too skinny, underage - style - TODAY.com". Today.msnbc.msn.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Darwell, Robert A.; Theodore C. Max; Edwin Komen; James A. Mercer III (29 October 2013). "The New Catwalk Experience: New York Tightens Laws for Underage Models". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Rusu, M (April 2013). "Interview with Catwalk Model Rusu" (Printed Publication). Expatriates Magazine. Paris. p. 33. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Vogt, Peter; Angie Wojak (2007). Career Opportunities in the Fashion Industry. Info base Publishing. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8160-6841-8.

- "Getting Started as a Model". associationofmodelagents.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- sawyer, Meieli. "how to become a plus size model". article. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Effron, Lauren (14 September 2011). "Fashion Models: By the Numbers". ABC News. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- Trebay, Guy (7 February 2008). "The Vanishing Point". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Nanci Hellmich, Do thin models warp girls' body image? Archived 2012-07-02 at the Wayback Machine USA Today 9/26/2006

- Skinny models banned from catwalk Archived 2006-11-24 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. September 13, 2006.

- Ban on stick-think models illegal Archived 2007-11-13 at the Wayback Machine, Jennifer Melocco, The Daily Telegraph, February 16, 2007.

- Kim Willsher, Models in France must provide doctor's note to work Archived 2016-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 18 December.

- Tran, Khan T.L. (1 May 2012). "Q&A: Paul Marciano on 30 Years of Guess Campaigns". wwd.com. Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Brown, Annie (3 July 2000). "Fashion's new Dahling; All Woman: Sophie Makes A Comeback with Three New Contracts and a Sexy, Slimmer Look". The Daily Record. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Serpe, Gina (8 February 2012). "Anna Nicole Smith's Death Five Years On: Timeline of a Tragedy". people.com. People Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Levi's Boyfriend Collection F/W 10". models.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Holt, Bethan (10 November 2018). "Why aren't there more 'middle' sized models in fashion?". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Why the Average American Woman Is Being Left Out of the Traditional Fashion Industry". Brit + Co. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Schlossberg, Mallory. "There's a group of women that the clothing industry is ignoring — and it's costing them tons of money". Business Insider. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Chernikoff, Leah (7 November 2014). "Myla Dalbesio on Her New Calvin Klein Campaign and the Rise of the 'In-Between' Model". ELLE. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Size 10 model: Controversy over my body 'so surreal'". TODAY.com. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "CAMILLE KOSTEK on Instagram: "Recently I experienced a situation that rattled me for a moment, so I wanted to take it to my page for whoever is open to reading.I made…"". Instagram. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "'Sports Illustrated' model Camille Kostek was told to adjust her measurements". yahoo.com. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Janette, Misha (16 September 2010). "A day in the life of a Japanese 'hostess' model". CNN. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Satsuki (7 December 2015). "How Dokumo, "Amateur Fashion Models", Have Been Making Impacts on Japanese Girls' Fashion Culture". Tokyo Girls Update. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Kobayashi, Tetsuo (14 January 2019). "女子大生読者モデルは平成で終わる?ファッション誌で激減。もう憧れの存在ではない。". Business Insider (in Japanese). Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Haidarali, Laila (2005). "Polishing Brown Diamonds: African American Women, Popular Magazines, and the Advent of Modeling in Early Postwar America". Journal of Women's History. 17 (1): 10–37. doi:10.1353/jowh.2005.0007. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 144395153.

- Newman, Scarlett L. (2017). "Black Models Matter: Challenging the Racism of Aesthetics and the Facade of Inclusion in the Fashion Industry". CUNY Academic Works – via Academic Works.

- Haynes, Clarence (24 June 2019). "Naomi Campbell and 10 Black Models Who Owned the Runway". Biography. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Givhan, Robin (6 September 2013). "Robin Givhan: Confronting the Lack of Black Models on the Runway". The Cut. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Trebay, Guy (8 May 2019). "At 45, Tyra Banks Is Back on the Cover of Sports Illustrated". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Fasanella, Kathleen (17 August 2010). "What is a fit model?". Fashion-Incubator:Lessons from the Sustainable Factory Floor. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Braid, Mary (14 September 2004). "UK | Magazine | Page Three girls – the naked truth". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Biography". Victoriasilvstedt.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Rebel Heart: An American Rock 'n' Roll Journey (13 August 2001). Rebel Heart: An American Rock 'n' Roll Journey: Bebe Buell, Victor Bockris: 9780312266943: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 0312266944.

- Gente (26 April 2008). "'Interviú' desnuda a Nereida Gallardo, la novia de Cristiano Ronaldo". 20minutos.es. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "BBC News – Sussex benefit cheat glamour model Dionne Stenner fined". Bbc.co.uk. 12 September 2011. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Big Brother: Only glamour models allowed – now". Nowmagazine.co.uk. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "MediaCorp launches Style: Men, ARENA to be closed" (Press release). MediaCorp. 30 April 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- "Newsbeat – Revealed: 'My body makes money'". BBC. 10 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Bianca Beauchamp Cosplay in Latex". Cosplay News Network. 6 August 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Cuh_Booom – It's Christie Jay". Cosplay News Network. 23 December 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Seaver, Linda. The Secret of Her Excess Oakland Tribune (8-13-87)

- Hare, Brianna (10 August 2009). "Their hands are worth 1,200 a day". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- "Meet the model who stands in for Kate Moss". Mirror. 18 September 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Susannah Cahalan (4 April 2010). "The sum of their parts". nypost.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- FoxNews.com (13 July 2002). "'Part' Time Modeling". FoxNews.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- "Cool Companies". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "About Carmen Hand Model Management". carmenhandmodels.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Herald Journal (30 March 2003). "A Model For Good Hand Care". Herald Journal. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Alan Burdick (July 2002). "I Was DeNiro's Leg: Tales from the parts-modeling industry". Alan Burdick. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- BellaSugar (11 August 2009). "Five Fun Facts About Hand Models". BellaSugar. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Jimi Okelana (10 March 2012). "Japan 101: Guide to Gravure Idols". Axiom Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Galbraith, P. W.; Karlin, J. G., eds. (30 August 2012). Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture. Springer, 2012. ISBN 978-1137283788.

- Mara Schiavocampo; Claire Pedersen; Timor Balaish; Lauren Effron (26 February 2015). "From Construction to High Fashion: How Instagram Helped This Male Model Get Discovered". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Heather Saul (27 March 2016). "Instafamous: Meet the social media influencers redefining celebrity". Independent. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Rosie Spinks (7 August 2016). "What It's Actually Like to Be an Instagram Model". Vice.

- "Instagram Models". Maxim. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Stephanie Smith (22 January 2014). "Curvy Instagram star Selter gets big sports deal". Page SIx. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Stephanie Radvan (13 March 2014). "Jen Selter Shows off her Famous Butt in "Vanity Fair"". Maxim. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "'Frozen' Lookalike, Anna Faith, Totally Looks Like Elsa". The Huffington Post Canada. 13 June 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- "Anna Faith Top Ten Cosplayer". Cosplay News Network. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "The Hottest Female Cosplayers On Instagram | Cosplay News Network". Cosplay News Network. 21 August 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "The Hottest Slave Leia Cosplay on Instagram". Cosplay News Network. 21 January 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Why Snapchat's Influencer Economy Runs on Hot Tubs, Selfies, and Whey Protein". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Blair, Olivia (5 October 2016). "Kayla Itsines: The personal trainer turned Instagram star on social media, body image and her new found fame". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Sam Webb (26 December 2015). "Millionaire models of Instagram: The stunning women you've never heard of raking in the cash on social media". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Teen temptations". Deccan Chronicle. 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Maya Oppenheim (6 September 2016). "This Instagram model has thousands of followers and they're mostly people trying to work out if she's fake or not". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "The model world of Instagram parody star Celeste Barber – in pictures". The Guardian. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Hunt, Elle (6 October 2016). "Who is Louise Delage? New Instagram influencer not what she seems". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Roberts, Sophie (30 August 2017). "Model reveals the truth about prostitution in the fashion industry". News Corp Australia. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Falzone, Diana (19 July 2016). "Insta-hookers? Sites say they expose 'Instagram models' who are really prostitutes". foxnews.com. Fox News. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Rachel, Hosie (12 January 2017). "Sexist websites are 'ruining lives' of women on Instagram, exposing them as 'escorts and prostitutes'". The Independent. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Models (people). |

- Gross, Michael. Model : the Ugly Business of Beautiful Women. New York: IT Books, 2011. ISBN 0-062-06790-7

- Hix, Charles, and Michael Taylor. Male Model: the World Behind the Camera. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1979. ISBN 0-312-50938-3

- Mears, Ashley (2011). Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26033-7.

- Vogels, Josey, and Smee, Tracy. "Object of Desire: Idealized Male Bodies Sell Everything from Underwear to Appliances; Are We Creating a Male Beauty Myth?" Hour (Montréal), vol. 3, no. 46 (14-20 Dec. 1995), p. [1], 10–11. N.B.: The caption title (on p. 10) is "Male Attention".

.jpg.webp)