Mollie Williams

Mollie Williams (born Mollie Hersh; March 18, 1884 – January 5, 1954) was an American burlesque artist and producer. She was best known for producing, writing, and starring in her own revue, The Mollie Williams Show.[1]

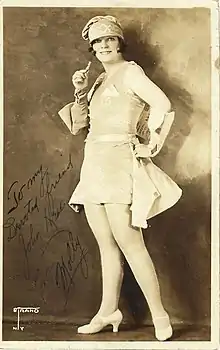

Mollie Williams | |

|---|---|

Strand Studio NY, 1924 | |

| Born | Mollie Hersh March 18, 1884 |

| Died | January 5, 1954 (aged 69) |

| Occupation | Actor, Producer, Writer, Comedienne |

| Years active | 1905-1920s |

| Spouse(s) | Albert Thetford (m. 1901) Hugh Dewart (m. 1946) |

| Children | Edwin Thetford (1903-1941) |

Early life

Mollie Hersh was born on March 18, 1884, in Manhattan, New York City.[2] She was one of four children born to Adolph Hersh and Henrietta (Miers) Hersh. Both Adolph and Henrietta descended from German Jewish immigrants and the family lived in East Harlem.[3]

Career

In 1905, Hersh appeared on stage at Miner's Bowery Theatre (originators of “get the hook”) using the name Mollie Williams.[4][5] Williams was subsequently signed as a chorus girl in Al Reeve's Big Beauty Show on the Eastern Burlesque Wheel. In 1907, while performing in the chorus of The Behman Show, Williams persuaded the producer to stage her impersonation of Anna Held. Williams' imitation of Held was a hit, one that led to principal roles in shows produced by Jack Singer and Robert Manchester.[6][7] During this time, Williams was known for her wisecracking comedy and risqué dramatic scenes, such as the Dance L’Enticement.[8][9]

With support from producer Max Spiegel, Williams became head of her own burlesque company in 1912.[10] As director and star of The Mollie Williams Show, she succeeded in creating a “snappy musical show [that] when in perfect running order ought to be ranking right up among leaders of the Eastern Wheel.”[11] The Mollie Williams Show featured a host of the Columbia Wheel's most talented comedians, soubrettes, and chorus girls. Williams herself appeared during the second act. She sang, danced, joked, and starred in dramatic playlets that she wrote. Williams kept the Dance L'Enticement in the show, but instead of performing it herself she gave it to the male comedians and played it for laughs. Citing Williams’ star power, Variety’s burlesque critic wrote, “burlesque boasts very few women of the Mollie Williams type. The lack of them is a prevailing weakness with most of the wheel shows...Mollie is a whole show in herself.”[12]

Williams began producing her own shows with her own company during the 1915–1916 season of The Mollie Williams Show.[13] It was around this time that she first performed her best known acts, namely a letter carrier ragtime number and a fashion show “for the ladies.”[14] Williams frequently touted her appeal with women. Early in her career, she told reporters that she tested new burlesque bits on her sisters.[9] Later, Williams admitted that she would listen closely to women in the audience and rewrite scenes until they laughed.[15] As a producer, Williams honed her image as a sympathetic boss, casting herself as a friend to the chorus girls because she had once been one herself.[16]

The Mollie Williams Show was a major financial success for the Columbia Wheel. Williams’ box office returns were second only to Jean Bedini, Columbia's top-performing male producer and performer.[8]

Postal Salary Readjustment Bill

The 1923–1924 season of The Mollie Williams Show smashed house records for ticket sales in major cities along the Columbia Wheel route. The show's success that year was due to Williams' public support for Senate Bill 1898, the Postal Salary Readjustment Bill. On the advice of the assistant superintendent of the Brooklyn Post Office, Williams used her popular letter carrier dance number to champion improved wages for postal workers. She went so far as to meet in Washington with the bill's sponsor, Pennsylvania Congressman Melville Clyde Kelly.[17]

Postal workers in numerous cities organized parades and parties in Williams’ honor. They bought tickets to The Mollie Williams Show for themselves and their families.[18] They "made it their business to mention that they had seen Miss Williams' show when delivering letters to households and that the show was a good one."[19]

Personal life

In 1901, Williams married Albert Thomas Thetford, an insurance agent from Brooklyn.[20] Two years later they had a son, Edwin Thetford, who was Williams’ only child. Edwin attended the New York Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb. He died in 1941.[21] In 1946, Williams married Hugh Dewart, President of Mohican Stores, Inc.[22][23]

Throughout her life, Williams dedicated herself to causes. In 1914, she turned down a leading role in Maurice Jacob's The Cherry Blossoms when the two failed to agree on a fair salary. Variety reported, “Miss Williams’ insistence upon a certain figure for her services has caused her to reject many offers that would have been decidedly alluring to almost any principal woman in burlesque.”[24] During that same year, she sued a motion picture company for royalties after they staged and filmed a traffic stop to catch her off guard.[25] As a producer, Williams staged overtly political material. For example, Williams' Wilson Show campaigned for the reelection of Woodrow Wilson during the Presidential Election of 1916.[26] Williams was an active member of the Actors Fund of America.[27]

Mollie Williams died in New York on January 5, 1954.[1] After a funeral service in University Chapel, she was buried next to her son, Edwin Thetford, at the Linden Hill Jewish Cemetery in Ridgewood, New York.[28]

References

- "Burlesque Bits". Billboard. January 23, 1954. p. 41.

- "New York, New York, Extracted Birth Index, 1878-1909". Ancestry.com.

- "Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900". Ancestry.com. Manhattan, New York, New York. Enumeration District: 0918.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Miner's Bowery Theatre". New York Clipper. October 7, 1905.

- Gerard, Barney (January 4, 1956). "Burlesque - Its Rise and Demise". Variety. p. 419.

- "The Behman Show". New York Clipper. October 24, 1908.

- "Manchester Signs Mollie". New York Clipper. April 16, 1910.

- Zeidman, Irving (1967). The American Burlesque Show. New York: Hawthorn Books.

- "Gossip of the Stage - Mollie Williams". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 12, 1908. p. 2.

- "Society and Drama". Washington Herald. November 24, 1912. p. 10.

- "Burlesque". Variety. September 6, 1912. pp. 32–33.

- "Mollie Williams Show". Variety. September 27, 1912. p. 26.

- "Lingerie, Drama, and Fun Blend in Williams Show". New York Clipper. October 18, 1916.

- "Gayety [advertisement]". Washington Herald. February 14, 1917. p. 10.

- "Says Women Are Best Judge of Plays". Dayton Daily News. October 24, 1926. p. 21.

- "Mollie Ever Was a Merry-Merry Herself, So Girls All Like Her". Omaha Sunday Bee. November 7, 1920. pp. 5-D.

- "Mollie Does Bit to Aid Mail Force". Dayton Daily News. March 6, 1924.

- "Postal Workers Here to Honor Mollie Williams". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 16, 1924.

- "Mollie Williams Tieup with Letter Carriers". Variety. February 28, 1924. pp. 1 and 27.

- "New York, New York, Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937". Ancestry.com.

- "New York, State Census, 1915". Ancestry.com.

- "New York, New York, Marriage License Indexes, 1907-2018". Ancestry.com.

- "Hugh Dewart, 73, Stores' Executive". New York Times. March 14, 1949. p. 19.

- "Mollie's Engagement Off". Variety. December 21, 1914.

- "Made Movie Star Against Her Will". Washington Times. January 17, 1914.

- "Columbia Has Wilson Show". New-York Tribune. October 17, 1916. p. 7.

- "Burlesque Booth at Fair". Variety. April 9, 1910.

- "Mollie Thetford". Find a Grave.

External links

Media related to Mollie Williams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mollie Williams at Wikimedia Commons- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "Mollie Williams". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "Mollie Williams, photographs". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "Mollie Williams". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Digital Repository, SUNY. "(sheet music) I Know You. By Andrew B. Sterling, Henry Lewis and Arthur Lange". Retrieved February 25, 2019.