Multiplicative group of integers modulo n

In modular arithmetic, the integers coprime (relatively prime) to n from the set of n non-negative integers form a group under multiplication modulo n, called the multiplicative group of integers modulo n. Equivalently, the elements of this group can be thought of as the congruence classes, also known as residues modulo n, that are coprime to n. Hence another name is the group of primitive residue classes modulo n. In the theory of rings, a branch of abstract algebra, it is described as the group of units of the ring of integers modulo n. Here units refers to elements with a multiplicative inverse, which in this ring are exactly those coprime to n.

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

This group, usually denoted , is fundamental in number theory. It has found applications in cryptography, integer factorization, and primality testing. It is an abelian, finite group whose order is given by Euler's totient function: For prime n the group is cyclic and in general the structure is easy to describe, though even for prime n no general formula for finding generators is known.

Group axioms

It is a straightforward exercise to show that, under multiplication, the set of congruence classes modulo n that are coprime to n satisfy the axioms for an abelian group.

Indeed, a is coprime to n if and only if gcd(a, n) = 1. Integers in the same congruence class a ≡ b (mod n) satisfy gcd(a, n) = gcd(b, n), hence one is coprime to n if and only if the other is. Thus the notion of congruence classes modulo n that are coprime to n is well-defined.

Since gcd(a, n) = 1 and gcd(b, n) = 1 implies gcd(ab, n) = 1, the set of classes coprime to n is closed under multiplication.

Integer multiplication respects the congruence classes, that is, a ≡ a' and b ≡ b' (mod n) implies ab ≡ a'b' (mod n). This implies that the multiplication is associative, commutative, and that the class of 1 is the unique multiplicative identity.

Finally, given a, the multiplicative inverse of a modulo n is an integer x satisfying ax ≡ 1 (mod n). It exists precisely when a is coprime to n, because in that case gcd(a, n) = 1 and by Bézout's lemma there are integers x and y satisfying ax + ny = 1. Notice that the equation ax + ny = 1 implies that x is coprime to n, so the multiplicative inverse belongs to the group.

Notation

The set of (congruence classes of) integers modulo n with the operations of addition and multiplication is a ring. It is denoted or (the notation refers to taking the quotient of integers modulo the ideal or consisting of the multiples of n). Outside of number theory the simpler notation is often used, though it can be confused with the p-adic integers when n is a prime number.

The multiplicative group of integers modulo n, which is the group of units in this ring, may be written as (depending on the author) (for German Einheit, which translates as unit), , or similar notations. This article uses

The notation refers to the cyclic group of order n. It is isomorphic to the group of integers modulo n under addition. Note that or may also refer to the group under addition. For example, the multiplicative group for a prime p is cyclic and hence isomorphic to the additive group , but the isomorphism is not obvious.

Structure

The order of the multiplicative group of integers modulo n is the number of integers in coprime to n. It is given by Euler's totient function: (sequence A000010 in the OEIS). For prime p, .

Cyclic case

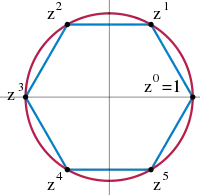

The group is cyclic if and only if n is 1, 2, 4, pk or 2pk, where p is an odd prime and k > 0. For all other values of n the group is not cyclic.[1][2][3] This was first proved by Gauss.[4]

This means that for these n:

- where

By definition, the group is cyclic if and only if it has a generator g (a generating set {g} of size one), that is, the powers give all possible residues modulo n coprime to n (the first powers give each exactly once). A generator of is called a primitive root modulo n.[5] If there is any generator, then there are of them.

Powers of 2

Modulo 1 any two integers are congruent, i.e., there is only one congruence class, [0], coprime to 1. Therefore, is the trivial group with φ(1) = 1 element. Because of its trivial nature, the case of congruences modulo 1 is generally ignored and some authors choose not to include the case of n = 1 in theorem statements.

Modulo 2 there is only one coprime congruence class, [1], so is the trivial group.

Modulo 4 there are two coprime congruence classes, [1] and [3], so the cyclic group with two elements.

Modulo 8 there are four coprime congruence classes, [1], [3], [5] and [7]. The square of each of these is 1, so the Klein four-group.

Modulo 16 there are eight coprime congruence classes [1], [3], [5], [7], [9], [11], [13] and [15]. is the 2-torsion subgroup (i.e., the square of each element is 1), so is not cyclic. The powers of 3, are a subgroup of order 4, as are the powers of 5, Thus

The pattern shown by 8 and 16 holds[6] for higher powers 2k, k > 2: is the 2-torsion subgroup (so is not cyclic) and the powers of 3 are a cyclic subgroup of order 2k − 2, so

General composite numbers

By the fundamental theorem of finite abelian groups, the group is isomorphic to a direct product of cyclic groups of prime power orders.

More specifically, the Chinese remainder theorem[7] says that if then the ring is the direct product of the rings corresponding to each of its prime power factors:

Similarly, the group of units is the direct product of the groups corresponding to each of the prime power factors:

For each odd prime power the corresponding factor is the cyclic group of order , which may further factor into cyclic groups of prime-power orders. For powers of 2 the factor is not cyclic unless k = 0, 1, 2, but factors into cyclic groups as described above.

The order of the group is the product of the orders of the cyclic groups in the direct product. The exponent of the group, that is, the least common multiple of the orders in the cyclic groups, is given by the Carmichael function (sequence A002322 in the OEIS). In other words, is the smallest number such that for each a coprime to n, holds. It divides and is equal to it if and only if the group is cyclic.

Subgroup of false witnesses

If n is composite, there exists a subgroup of the multiplicative group, called the "group of false witnesses", in which the elements, when raised to the power n − 1, are congruent to 1 modulo n (since the residue 1, to any power, is congruent to 1 modulo n, the set of such elements is nonempty).[8] One could say, because of Fermat's Little Theorem, that such residues are "false positives" or "false witnesses" for the primality of n. The number 2 is the residue most often used in this basic primality check, hence 341 = 11 × 31 is famous since 2340 is congruent to 1 modulo 341, and 341 is the smallest such composite number (with respect to 2). For 341, the false witnesses subgroup contains 100 residues and so is of index 3 inside the 300 element multiplicative group mod 341.

n = 9

The smallest example with a nontrivial subgroup of false witnesses is 9 = 3 × 3. There are 6 residues coprime to 9: 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8. Since 8 is congruent to −1 modulo 9, it follows that 88 is congruent to 1 modulo 9. So 1 and 8 are false positives for the "primality" of 9 (since 9 is not actually prime). These are in fact the only ones, so the subgroup {1,8} is the subgroup of false witnesses. The same argument shows that n − 1 is a "false witness" for any odd composite n.

n = 91

For n = 91 (= 7 × 13), there are residues coprime to 91, half of them (i.e., 36 of them) are false witnesses of 91, namely 1, 3, 4, 9, 10, 12, 16, 17, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30, 36, 38, 40, 43, 48, 51, 53, 55, 61, 62, 64, 66, 68, 69, 74, 75, 79, 81, 82, 87, 88, and 90, since for these values of x, x90 is congruent to 1 mod 91.

n = 561

n = 561 (= 3 × 11 × 17) is a Carmichael number, thus s560 is congruent to 1 modulo 561 for any integer s coprime to 561. The subgroup of false witnesses is, in this case, not proper; it is the entire group of multiplicative units modulo 561, which consists of 320 residues.

Examples

This table shows the cyclic decomposition of and a generating set for n ≤ 128. The decomposition and generating sets are not unique; for example, (but ). The table below lists the shortest decomposition (among those, the lexicographically first is chosen – this guarantees isomorphic groups are listed with the same decompositions). The generating set is also chosen to be as short as possible, and for n with primitive root, the smallest primitive root modulo n is listed.

For example, take . Then means that the order of the group is 8 (i.e., there are 8 numbers less than 20 and coprime to it); means the order of each element divides 4, that is, the fourth power of any number coprime to 20 is congruent to 1 (mod 20). The set {3,19} generates the group, which means that every element of is of the form 3a × 19b (where a is 0, 1, 2, or 3, because the element 3 has order 4, and similarly b is 0 or 1, because the element 19 has order 2).

Smallest primitive root mod n are (0 if no root exists)

- 0, 1, 2, 3, 2, 5, 3, 0, 2, 3, 2, 0, 2, 3, 0, 0, 3, 5, 2, 0, 0, 7, 5, 0, 2, 7, 2, 0, 2, 0, 3, 0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 2, 3, 0, 0, 6, 0, 3, 0, 0, 5, 5, 0, 3, 3, 0, 0, 2, 5, 0, 0, 0, 3, 2, 0, 2, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 7, 0, 5, 5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 0, 2, 7, 2, 0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 3, 0, ... (sequence A046145 in the OEIS)

Numbers of the elements in a minimal generating set of mod n are

- 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1, 1, 1, 3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, ... (sequence A046072 in the OEIS)

| Generating set | Generating set | Generating set | Generating set | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 33 | C2×C10 | 20 | 10 | 2, 10 | 65 | C4×C12 | 48 | 12 | 2, 12 | 97 | C96 | 96 | 96 | 5 | |||

| 2 | C1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 34 | C16 | 16 | 16 | 3 | 66 | C2×C10 | 20 | 10 | 5, 7 | 98 | C42 | 42 | 42 | 3 | |||

| 3 | C2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 35 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 2, 6 | 67 | C66 | 66 | 66 | 2 | 99 | C2×C30 | 60 | 30 | 2, 5 | |||

| 4 | C2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 36 | C2×C6 | 12 | 6 | 5, 19 | 68 | C2×C16 | 32 | 16 | 3, 67 | 100 | C2×C20 | 40 | 20 | 3, 99 | |||

| 5 | C4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 37 | C36 | 36 | 36 | 2 | 69 | C2×C22 | 44 | 22 | 2, 68 | 101 | C100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | |||

| 6 | C2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 38 | C18 | 18 | 18 | 3 | 70 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 3, 69 | 102 | C2×C16 | 32 | 16 | 5, 101 | |||

| 7 | C6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 39 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 2, 38 | 71 | C70 | 70 | 70 | 7 | 103 | C102 | 102 | 102 | 5 | |||

| 8 | C2×C2 | 4 | 2 | 3, 5 | 40 | C2×C2×C4 | 16 | 4 | 3, 11, 39 | 72 | C2×C2×C6 | 24 | 6 | 5, 17, 19 | 104 | C2×C2×C12 | 48 | 12 | 3, 5, 103 | |||

| 9 | C6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 41 | C40 | 40 | 40 | 6 | 73 | C72 | 72 | 72 | 5 | 105 | C2×C2×C12 | 48 | 12 | 2, 29, 41 | |||

| 10 | C4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 42 | C2×C6 | 12 | 6 | 5, 13 | 74 | C36 | 36 | 36 | 5 | 106 | C52 | 52 | 52 | 3 | |||

| 11 | C10 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 43 | C42 | 42 | 42 | 3 | 75 | C2×C20 | 40 | 20 | 2, 74 | 107 | C106 | 106 | 106 | 2 | |||

| 12 | C2×C2 | 4 | 2 | 5, 7 | 44 | C2×C10 | 20 | 10 | 3, 43 | 76 | C2×C18 | 36 | 18 | 3, 37 | 108 | C2×C18 | 36 | 18 | 5, 107 | |||

| 13 | C12 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 45 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 2, 44 | 77 | C2×C30 | 60 | 30 | 2, 76 | 109 | C108 | 108 | 108 | 6 | |||

| 14 | C6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 46 | C22 | 22 | 22 | 5 | 78 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 5, 7 | 110 | C2×C20 | 40 | 20 | 3, 109 | |||

| 15 | C2×C4 | 8 | 4 | 2, 14 | 47 | C46 | 46 | 46 | 5 | 79 | C78 | 78 | 78 | 3 | 111 | C2×C36 | 72 | 36 | 2, 110 | |||

| 16 | C2×C4 | 8 | 4 | 3, 15 | 48 | C2×C2×C4 | 16 | 4 | 5, 7, 47 | 80 | C2×C4×C4 | 32 | 4 | 3, 7, 79 | 112 | C2×C2×C12 | 48 | 12 | 3, 5, 111 | |||

| 17 | C16 | 16 | 16 | 3 | 49 | C42 | 42 | 42 | 3 | 81 | C54 | 54 | 54 | 2 | 113 | C112 | 112 | 112 | 3 | |||

| 18 | C6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 50 | C20 | 20 | 20 | 3 | 82 | C40 | 40 | 40 | 7 | 114 | C2×C18 | 36 | 18 | 5, 37 | |||

| 19 | C18 | 18 | 18 | 2 | 51 | C2×C16 | 32 | 16 | 5, 50 | 83 | C82 | 82 | 82 | 2 | 115 | C2×C44 | 88 | 44 | 2, 114 | |||

| 20 | C2×C4 | 8 | 4 | 3, 19 | 52 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 7, 51 | 84 | C2×C2×C6 | 24 | 6 | 5, 11, 13 | 116 | C2×C28 | 56 | 28 | 3, 115 | |||

| 21 | C2×C6 | 12 | 6 | 2, 20 | 53 | C52 | 52 | 52 | 2 | 85 | C4×C16 | 64 | 16 | 2, 3 | 117 | C6×C12 | 72 | 12 | 2, 17 | |||

| 22 | C10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 54 | C18 | 18 | 18 | 5 | 86 | C42 | 42 | 42 | 3 | 118 | C58 | 58 | 58 | 11 | |||

| 23 | C22 | 22 | 22 | 5 | 55 | C2×C20 | 40 | 20 | 2, 21 | 87 | C2×C28 | 56 | 28 | 2, 86 | 119 | C2×C48 | 96 | 48 | 3, 118 | |||

| 24 | C2×C2×C2 | 8 | 2 | 5, 7, 13 | 56 | C2×C2×C6 | 24 | 6 | 3, 13, 29 | 88 | C2×C2×C10 | 40 | 10 | 3, 5, 7 | 120 | C2×C2×C2×C4 | 32 | 4 | 7, 11, 19, 29 | |||

| 25 | C20 | 20 | 20 | 2 | 57 | C2×C18 | 36 | 18 | 2, 20 | 89 | C88 | 88 | 88 | 3 | 121 | C110 | 110 | 110 | 2 | |||

| 26 | C12 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 58 | C28 | 28 | 28 | 3 | 90 | C2×C12 | 24 | 12 | 7, 11 | 122 | C60 | 60 | 60 | 7 | |||

| 27 | C18 | 18 | 18 | 2 | 59 | C58 | 58 | 58 | 2 | 91 | C6×C12 | 72 | 12 | 2, 3 | 123 | C2×C40 | 80 | 40 | 7, 83 | |||

| 28 | C2×C6 | 12 | 6 | 3, 13 | 60 | C2×C2×C4 | 16 | 4 | 7, 11, 19 | 92 | C2×C22 | 44 | 22 | 3, 91 | 124 | C2×C30 | 60 | 30 | 3, 61 | |||

| 29 | C28 | 28 | 28 | 2 | 61 | C60 | 60 | 60 | 2 | 93 | C2×C30 | 60 | 30 | 11, 61 | 125 | C100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | |||

| 30 | C2×C4 | 8 | 4 | 7, 11 | 62 | C30 | 30 | 30 | 3 | 94 | C46 | 46 | 46 | 5 | 126 | C6×C6 | 36 | 6 | 5, 13 | |||

| 31 | C30 | 30 | 30 | 3 | 63 | C6×C6 | 36 | 6 | 2, 5 | 95 | C2×C36 | 72 | 36 | 2, 94 | 127 | C126 | 126 | 126 | 3 | |||

| 32 | C2×C8 | 16 | 8 | 3, 31 | 64 | C2×C16 | 32 | 16 | 3, 63 | 96 | C2×C2×C8 | 32 | 8 | 5, 17, 31 | 128 | C2×C32 | 64 | 32 | 3, 127 |

See also

Notes

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Modulo Multiplication Group". MathWorld.

- Primitive root, Encyclopedia of Mathematics

- (Vinogradov 2003, pp. 105–121, § VI PRIMITIVE ROOTS AND INDICES)

- (Gauss & Clarke 1986, arts. 52–56, 82–891)

- (Vinogradov 2003, p. 106)

- (Gauss & Clarke 1986, arts. 90–91)

- Riesel covers all of this. (Riesel 1994, pp. 267–275)

- Erdős, Paul; Pomerance, Carl (1986). "On the number of false witnesses for a composite number". Math. Comput. 46 (173): 259–279. doi:10.1090/s0025-5718-1986-0815848-x. Zbl 0586.10003.

References

The Disquisitiones Arithmeticae has been translated from Gauss's Ciceronian Latin into English and German. The German edition includes all of his papers on number theory: all the proofs of quadratic reciprocity, the determination of the sign of the Gauss sum, the investigations into biquadratic reciprocity, and unpublished notes.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Clarke, Arthur A. (translator into English) (1986), Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (Second, corrected edition), New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-96254-2

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Maser, H. (translator into German) (1965), Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithemeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition), New York: Chelsea, ISBN 978-0-8284-0191-3

- Riesel, Hans (1994), Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorization (second edition), Boston: Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-3743-9

- Vinogradov, I. M. (2003), "§ VI PRIMITIVE ROOTS AND INDICES", Elements of Number Theory, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, pp. 105–121, ISBN 978-0-486-49530-9