Murders of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Peña

The rapes and murders of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Peña, two teenaged girls from Houston, Texas, aged 14 and 16, respectively, occurred on June 24, 1993. The murder of the two girls made headlines in Texas newspapers due to the nature of the crime and the new law resulting from the murder that allows families of the victims to view the execution of the murderers. The case was also notable in that the state of Texas rejected attempts by the International Court of Justice to halt the executions of several of the perpetrators.

| Murders of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Peña | |

|---|---|

Elizabeth Peña and Jennifer Ertman | |

| Location | Oak Forest, Houston, Texas, United States |

| Date | June 24, 1993 |

Attack type | Murder, gang rape, torture, sexual assault, kidnapping |

| Weapons | Ligatures, belt |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Perpetrators | Peter Cantu José Medellín Sean Derrick O'Brien Efrain Perez Raul Villarreal Venancio Medellín |

No. of participants | 6 |

| Verdict | Death (Cantu, J. Medellín, O'Brien, Perez, Villarreal) 40 years (V. Medellín) |

The death sentences of Efrain Perez and Raul Villarreal were commuted to life imprisonment in 2005, following Roper v. Simmons | |

Murder

On June 24, 1993, Jennifer Louise Ertman (August 15, 1978 – June 24, 1993) and Elizabeth Christine Peña (June 21, 1977 – June 24, 1993), Waltrip High School students, were attending the pool party of a friend who lived in the Spring Hill Apartments. When the pair realized that they were going to be late returning home, they decided to leave the party to meet an 11:30 pm curfew.[1] Ertman and Peña decided to take a 10-minute shortcut to Peña's residence in Oak Forest by following the railroad tracks and then passing through T.C. Jester Park.[2]

The girls were walking along the White Oak Bayou when they encountered "Black and White" gang members drinking beer after holding a gang initiation.[3]

The gang kidnapped Peña, and Ertman had initially escaped, but was kidnapped after she ran back to help her friend when she screamed. The six gang members raped the girls repeatedly. After realizing that the girls might identify them, Peter Anthony Cantu,[4] a leader of the gang, ordered the members to kill the girls, so the members strangled them to death.[2] Derrick Sean O'Brien and Raul Omar Villarreal strangled Ertman with a red nylon belt before the belt broke; then the gang members used shoelaces.[2][3] Cantu, José Medellín, and Efrain Perez strangled Peña with shoelaces. The members then stomped on the girls' throats to ensure their deaths.[2]

Cantu, Medellín, Perez, and Villarreal then met at Cantu's residence, where he lived with his brother, Joe Cantu, and sister-in-law, Christina Cantu. Christina Cantu questioned why Villarreal was bleeding and Perez had a bloody shirt. This prompted Medellín to say the gang "had fun" and that details would appear on the news. He then elaborated that he had raped both girls.[5]

Peter Cantu then returned, and divided valuables that had been stolen from the girls. José Medellín got a ring with an "E", so he could give it to his girlfriend, Esther. Medellín reported that he had killed a girl, and noted that he would have found it easier with a gun. O'Brien was videotaped smiling at the scene of the crime. After the gang left, Christina Cantu convinced Joe Cantu to report the crime to police.[6]

Four days after the crime, the bodies were found in the park during hot weather conditions. They were badly decaying, and dental records were used for identification. The medical examiner corroborated that the cause of death was strangulation. All those believed responsible were ultimately arrested. Medellín gave both written and taped confessions.[7][8][9]

Sentencing, incarceration, and executions

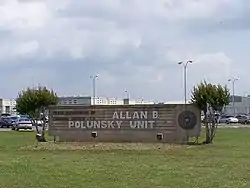

At sentencing, the offenders were remanded to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) system. Peter Anthony Cantu, José Ernesto Medellín, Derrick Sean O'Brien, Efrain Perez, and Raul Omar Villarreal received death sentences. Venancio Medellín, the brother of José Medellín, was 14 at the time of the murder, the same age as Jennifer Ertman. Venancio received a 40-year prison sentence. When the Supreme Court of the United States banned the executions of people who committed crimes while they were below 18 years of age, the sentences of Perez and Villarreal were automatically commuted to life in prison.[3] O'Brien, an African American and the only non-Hispanic in the gang, was the first to be executed, in July 2006. O'Brien was buried in the Captain Joe Byrd Cemetery in Huntsville, Texas.[2][10]

José Ernesto Medellín appealed his execution, saying that he had informed City of Houston and Harris County police officers that he was a Mexican citizen, and that he had been unable to confer with Mexican consular officials. The prosecutors said that Medellín never told authorities that he was a Mexican citizen. Medellín said in a sworn statement that he learned that the Mexican consulate could assist him in 1997.[11] He petitioned the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in 1998 regarding this issue; the appeal failed.[12]

Medellín's impending execution became an international controversy, since the state did not hold a hearing about whether the inability for Medellín to meet with Mexican consular officials harmed his defense. The right of a defendant to talk with his or her consulate is specified in the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations; the United States is a party to the convention, although the U.S. withdrew from compulsory jurisdiction in 1986 to accept the court's jurisdiction only on a case-by-case basis.[13] In 2004, the International Court of Justice responded to a lawsuit filed by Mexico against the United States; the court ordered hearings to be held for inmates, including Medellín, who were denied consular rights.[14]

In 2005, President George W. Bush ordered hearings to be held. The State of Texas, represented by Solicitor General Ted Cruz, challenged Bush's order, and the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that only the Congress of the United States has the right to order hearings to be held. In July, the World Court ordered a stay of Medellín's execution. Governor Rick Perry argued that Texas is not bound to World Court rulings. Death penalty opponents protested the impending execution. The families of both Ertman and Peña strongly favored the execution(s).[2]

Randy Ertman (1952–2014), father of Jennifer Ertman, wanted to have Andy Kahan, the City of Houston's crime advocate, witness the execution of Medellín. TDCJ refused to permit Kahan to witness the execution.[15] Michelle Lyons, a TDCJ official, said that Tropical Storm Edouard would likely not be a factor preventing the execution of Medellín.[16]

José Ernesto Medellín was executed at 9:57 pm on August 5, 2008, after his last-minute appeals were rejected by the Supreme Court.[17] Governor Perry rejected calls from Mexico and Washington, DC, to delay the execution, citing the torture, rape, and strangulation of two teenaged girls in Houston 15 years ago as just cause for the death penalty.[18] During his lifetime, Randy Ertman advocated strongly against granting parole to Venancio Medellín.[19]

Seventeen years after the crimes, Peter Anthony Cantu was executed on August 17, 2010.[20] The lethal injection was performed at 6:09 pm, and at 6:17 pm, Cantu was officially pronounced dead.[21]

In 2020 the Texas parole board denied parole to Medellin.[22]

Aftermath

The parents of the murder victims successfully advocated for the State of Texas allowing relatives of victims to have permission to witness executions.[3] Before the murders, Houston officials had stated that gangs were not a significant issue in the city. C.E. Anderson, a Houston Police Department officer who worked on the murder case, described the murder as "part of the impetus for the antigang programs in Houston." Jennifer Latson of the Houston Chronicle said that the deaths of the girls "shook" the Oak Forest neighborhood of Houston "to its foundation."[23]

Waltrip High School has a memorial to the girls.[24] Another memorial exists at T.C. Jester Park.[23]

See also

References

- Hayes, Kevin (August 17, 2010). "Peter Anthony Cantu Execution: Mastermind of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Pena Murders to Die Tonight". CBS News. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- Turner, Allan. "Medellin set to die Tuesday for Ertman-Peña killings", Houston Chronicle. August 4, 2008; retrieved March 6, 2010.

- Graczyk, Michael. ""Convicted killer of teenage Houston girls set to die."". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2010-03-06.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Associated Press at MySanAntonio.com, July 10, 2006; retrieved June 26, 2009.

- Clarkprosecutor.org: Peter Anthony Cantu- Reviewed 2017-05-07

- Allan Turner, Rosanna Ruiz (August 6, 2008). "Medellin executed for rape, murder of Houston teens". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved July 20, 2011.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Murder of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Peña, clarkprosecutor.org; accessed June 4, 2016.

- Underwood, Melissa (October 10, 2007). "Father of Murdered Girl Questions Bush's Support to Halt Killer's Execution". FOX News. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- "Media Advisory: Jose Medellin Scheduled For Execution". Attorney General of Texas. July 29, 2008. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- "San Antonio turned from bully to savage killer". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. February 14, 1994. p. 5A. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- Ross, Robyn. Laid to Rest in Huntsville (Archive) Texas Observer. Tuesday, March 11, 2014; retrieved March 16, 2014.

- law.justia.com

- law.cornell.edu

- Churchill, Ward. A Little Matter of Genocide, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1997.

- object.cato.org

- Vogel, Chris. Victim's "Advocate Won't be Witnessing Execution", Houston Press, July 30, 2008; retrieved March 6, 2010.

- "Can Edouard Save Jose Medellin?", Houston Press, August 5, 2008; retrieved March 6, 2010.

- Supreme Court of the United States (August 5, 2008). "José Ernesto Medellín v. Texas (Per Curiam)" (PDF). SCOTUS blog. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- McKinley, James C., Jr. (August 6, 2008). "Texas Executes Mexican Despite Objections". New York Times.

- Watkins, Andrea and Damali Keith. "Dad confronts parole board to keep daughter's murderer in prison" Archived 2014-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, myfoxhouston.com, September 5, 2012; accessed March 16, 2014.

- "Last Statement Peter Cantu." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on January 11, 2017.

- Tolson, Mike (2010-08-17). "Ex-gang leader executed for '93 deaths of 2 Houston girls". Houston Chronicle.

- "Parole denied for gang member convicted in 1993 murders of Jennifer Ertman and Elizabeth Pena". KTRK-TV. 2020-11-14. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Latson, Jennifer. Somber tribute held to the teen victims", Houston Chronicle, August 6, 2008; retrieved March 7, 2010.

- "In Memory of Elizabeth Peña and Jennifer Ertman - 1993." Waltrip High School; retrieved March 6, 2010.

Further reading

- Mitchell, Corey. Pure Murder. Pinnacle Books, 2008. ISBN 0786018518, 9780786018512. Available at Google Books.

- "Peter A. Cantu, Texas Executed August 17" (Chapter 35). In: Mangino, Matthew T. The Executioner's Toll, 2010: The Crimes, Arrests, Trials, Appeals, Last Meals, Final Words and Executions of 46 Persons in the United States. McFarland & Company, April 16, 2014. ISBN 0786479795, 9780786479795. START: p. 158.