Murnong

Murnong and yam daisy are common names for the plants Microseris walteri, Microseris lanceolata and Microseris scapigera, which were an important food source for Indigenous people in Australia.

The roots of the murnong plants were consumed in high quantities by Indigenous people until the 1840s, when European colonists began using the murnong crop lands for sheep farming. [1]

The binomial names of the three species are often misidentified, because they were classified under different names until they were clarified in 2016. Murnong is often described as growing a sweet tuber, but this identifies Microseris walteri rather than the other two plants, which have bitter roots. [2]

Botanical naming

For more than 30 years Murnong was named as Microseris sp. or Microseris lanceolata or Microseris scapigera. Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria botanist Neville Walsh clarified the botanical name of Microseris walteri in 2016 and defined the differences in the three species in the table below.[2]

| Feature | Microseris walteri | Microseris lanceolata | Microseris scapigera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | single fleshy root expanding to a solitary, napiform to narrow-ellipsoid or narrow-ovoid, annually replaced tuber | several fleshy roots, cylindrical to long-tapered, branching just below ground-level | several cylindrical or long-tapered, usually branched shortly below leaves |

| Images of roots |  M. walteri tuber roots |

M. lanceolata tapered roots |

M. scapigera tapered roots |

| Fruit (Capsela) | usually less than 7mm long | usually less than 7mm long | mostly 7–10 mm long |

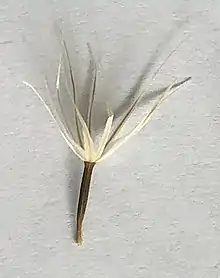

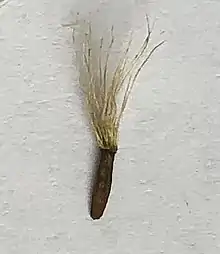

| Images of seeds |  Microseris walteri seed |

Microseris lanceolata seed |

Microseris scapigera seed |

| Pappus bristles | c. 10 mm long, 0.5–1.3mm wide at base | 10–20 mm long, c. 0.3–0.5 mm wide at base | 30–66 mm long |

| Images of flowers |  M. walteri flower, approx 4cm wide |

M. lanceolata flower, approx 5cm wide |

M. scapigera flower, approx 2cm wide |

| Joined petals (Ligule) | usually more than 15mm long | usually more than 15mm long | up to 12mm long |

| Origin | lowlands of temperate southern WA, SA, NSW, ACT, Victoria and Tasmania | rarely on basalt soils; alpine and subalpine NSW, ACT and Victoria | mostly from basalt plains of western Victoria and elevated sites in Tasmania |

| Taste of roots | sweet-tasting, both raw and cooked | bitter, slightly fibrous and not particularly palatable | slightly fibrous, and slightly, but tolerably bitter |

Indigenous names of Murnong

Murnong is a Woiwurrung word for the plant, used by the Wurundjeri people and possibly other clans of the Kulin nation. It has many other names in other Australian Indigenous languages. [1] Below is a list of the indigenous names, language groups and locations where the name was recorded.

- murnong, mernong, mirr-n'yong, myrnong, wuleli. Woiwurrung (Melbourne) [3]

- dirrinan. Wiradjuri (Mudgee, NSW)

- dalu-mlarng,[3] mlang,[4] moit-bar-dyul. Gunai/Kurnai (Gippsland, Vic)

- keerang, yuwatch (cooked root). Peek Whuurong (Port Fairy, Vic)

- kool-an-gur. Wannin (Wannon, Vic)

- maiela. Bangerang (Echuca, Vic)

- maiyilla.[4] Yorta Yorta (Echuca, Vic)

- maranong. Wathawurrung (Trawalla, central Vic)

- midyini. Dharug (Sydney)

- meerwan. Wemba Wemba (Lake Bogal, Vic)

- mingar (Mudgee, NSW)

- mo-i-yool. Ngoorialum (Colbinabbin, Vic)

- mo-ner, moo-nar. Dja Dja Wurrung (East of Grampians)

- moonang (Bacchus Marsh, Vic)

- moonya[4] (Lake Albacutya, Vic)

- mooranong (Hamilton, Vic)

- munja. Wergaia (Mallee, Vic)

- munya, bam-munya. Wotjobaluk (Lake Hindmarsh, Vic)

- murning Wathawurrung (Geelong, Vic)

- muurang, yuwatch (cooked root). Kuurn Kopan Noot (North of Port Fairy, Vic)

- myrnong (Mortlake, Vic)[3]

- ngamko.[7] Thura-Yura (Lower Murray, SA)

- njamang. Southern Ngarigu (Gippsland, Vic)

- pun-nin. Waverang (West of Mt Cole, Vic)

- pun'-yin, taluum. Chaap Wuurong (Mt Rouse, Vic)

- tao.[9] (Lachlan River, Regent Lake, Bogan River, NSW)

- thabor. Watiwati (Tyntynder, Vic)

- yerat. (Lake Condah, Vic) [3]

Uses and cultivation

The edible tuberous roots of murnong plants were once a vitally important source of food for Aboriginal Australian people in the southern parts of Australia. Indigenous women would dig for roots with a digging stick, also known as a yam stick, and they would carry the roots in a dillybag. They would place the whole dillybag of tubers onto a mirnyong (earth oven) to roast the tubers. [1][10] Another cooking technique places heated clay elements placed above and below the edible roots. The steam and moisture helps reduce the drying and shrinking of the vegetables.[11]

Early records

In 1835, convict William Buckley escaped from the settlement at Sullivan’s Bay near Sorrento, Victoria and lived among the Wathaurong people at the mouth of Thompson Creek. An important source of food for Buckley 'was a particular kind of root the natives call Murning — in shape, and size, and flavour, very much resembling the radish.'[12]

Port Phillip settler James Malcolm testified in front of the NSW parliament on the condition of Indigenous people in 1845. Malcolm said, 'There is a nutritious root which [the Indigenous people] eat and are fond of; and that, I think, has greatly diminished, from the grazing of sheep and cattle over the land, because I have not seen so many of the flowers of it in the spring as I used to see. It bears a beautiful yellow flower. The native name of this root is "murnong".'[13]

Malcolm referenced Buckley in his description of murnong. He said, 'It is rather agreeable to the taste as a native article of food, and when you squeeze it, there is a sort of milk or creamy substance which comes out of it. I have eaten it many a time, and a man named Buckley who lived among the natives for thirty years before the settlement was formed, tells me, that a man may live on the root for weeks together; and that he has dug them up in great numbers for food.'[13]

In 1835, the Tasmanian colonist John Batman set up his base camp for the land speculation company Port Phillip Association at Indented Head. While he returned to Tasmania to collect his family and additional provisions, the members left at the Indented Head camp were running low on imported food supplies, so they began to eat murnong. The servant William Todd wrote, 'We have commenced eating roots the same as the natives do.'[14]

Surveyor and explorer Thomas Mitchell came across a community of Aboriginal people who cultivated and harvested murnong tubers with specialised tools on the plains around the Hopkins River on 17 September 1835. Mitchell was wary and when 40 of them approached his camp, he ordered his men to charge at them.[9]

Sheep and cattle grazing

The introduction of cattle, sheep and goats by immigrating early–colonialist Europeans led to the near extinction of murnong, with calamitous results for Indigenous communities who depended upon murnong for a large part of their food.[1] Mitchell had noted that 'the cattle are very fond of the leaves of this plant, and seem to thrive upon it'.[9] Sheep were more destructive, since the murnong was most abundant on the plains and open forests where sheep were introduced.[1]

Richmond Hill Massacre

From 1794 to 1816, British soldiers fought against Indigenous clans inhabiting the Hawkesbury River region and the surrounding areas to the west of Sydney. Four hundred British settlers moved into the area in 1794 and began to construct farms along the river, some established by soldiers. The midyini (murnong) yam beds around the river were removed and corn was planted. [15] When the corn was ripening, a report stated that there were sightings of Aboriginal people intending to take the corn. Darug man Chris Tobin wrote, 'Sixty Red Coats were deployed under the instruction to hang any Aboriginal person they killed to drive away others.' The soldiers found Indigenous camps at night and shot the people. An unknown number died. Tobin said, 'They took five prisoners to Parramatta, one of the women taken was carrying a baby who had been shot through her body. The baby died in hospital and the prisoners were released three days later.'[16]

In remembrance of the colonial violence across the region, a Memorial Fire Place was built in 2002 on the land of the St John of God Hospital in North Richmond, NSW.[17]

Artwork

In 2019, the National Gallery of Victoria commissioned a large sculpture called 'In Absence' by Yhonnie Scarce and Melbourne architecture studio Edition Office. The artwork questions the absence of murnong in Victoria, which were once plentiful prior to colonisation. The artwork consists of wooden tower rises upwards from a surrounding field of kangaroo grass, murnong and a path of crushed Victorian basalt. The 9 metre high by 10 metre wide cylinder is clad in a dark-stained Tasmanian hardwood. A narrow vertical aperture, slicing the tall cylinder open, bisects the tower leaving a void and creating a passage into two curved chambers. Inside each, hundreds of hand-blown, glossy, black glass murnong populate the walls and glitter in shafts of sunlight. [18]

References

- Gott, Beth (1983). "Murnong—Microseris scapigera: a study of a staple food of Victorian Aborigines". Australian Aboriginal Studies. 2.

- Walsh, Neville (2016). "A name for Murnong (Microseris: Asteraceae: Cichorioideae)" (PDF). Muelleria. 34.

- Smyth, Robert Brough (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria. Melbourne: J Ferres, gov't printer.

- Robert Hamilton, Mathews (1902), The Aboriginal languages of Victoria, Royal Society of New South Wales

- Amery, Rob (2015). Warraparna Kaurna! Reclaiming an Australian language (PDF). Adelaide: University of Adelaide. ISBN 9781925261240.

- Robert Hamilton, Mathews (1908), Vocabulary of the Ngarrugu tribe N.S.W., Sydney: Royal Society of New South Wales, nla.obj-756524402, retrieved 7 February 2021 – via Trove

- Moorhouse, Matthew (1846). A vocabulary of the Murray River language from Wellington on the Murray. Andrew Murray.

- Williams, Alice; Sides, Tim. "Wiradjuri Plant Use in the Murrumbidgee Catchment" (PDF). NSW Local Land Services. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Mitchell, Thomas (1838). Journal of an Expedition to the rivers Darling and Murray in the year 1836 in Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia. London: T. & W. Boone.

- Gott, Beth; Conran, John (1991). Victorian Koorie plants : some plants used by Victorian Koories for food, fibre, medicines and implements. Hamilton and Western District Museum. Yangennanock Women's Group, Aboriginal Keeping Place. ISBN 978-0-646-03846-9.

- Campanelli, Maurizio; Muir, Jane; Mora, Alice; Clarke, Daniel; Griffin, Darren (2015). "Re-Creating an Aboriginal Earth Oven with Clayey Heating Elements: Experimental Archaeology and Paleodietary Implications". Experimental Archaeology.

- Morgan, John (1852). The life and adventures of William Buckley (PDF). Canberra: ANU Press.

- Malcolm, James (11 September 1845). NSW Legislative Council Select Committee (PDF). New South Wales.

- Boyce, James (2011). 1835: the Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia. Melbourne: Black Inc. p. 95.

- Macintyre, Stuart (1999). A Concise History of Australia. Cambridge Concise Histories (First ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62577-7.

- Knowles, Rachael (8 November 2019). "Dharug massacre memorial site teaches young Aboriginal students about colonial history".

- "Battle of Richmond Hill". Monument Australia. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- McEoin, Ewan. "In Absence, Yhonnie Scarce and Edition Office". 2019 NGV Architecture Commission. Retrieved 31 January 2021.