Nagpuri people

Nagpuris are an Indo-Aryan-speaking ethnolinguistic group who traditionally speak Nagpuri as their mother tongue and native to western Chota Nagpur Plateau region of Indian state Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Odisha.[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 4 – c. 5 million [1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal, Assam | |

| Languages | |

| Nagpuri • Hindi • Odia • Bengali • Assamese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Minorities: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Etymology

Historically the native speaker of Sadri/Nagpuri language are known as Sadan. Sadan means non-tribal Indo-Aryan language speaker who traditionally speak Nagpuri, Khortha, Panchpargania and Kurmali.[3] The Nagpuri as a linguistic and cultural identity is perhaps origin of early modern period. The known use of name Nagpuri was first used by king Medini Ray for Nagvanshi king Raghunath Shah. The name "Nagpuri" has been propagated by poets and writers. In recent years the native speaker of Sadri/Nagpuri language are known as Nagpuri in western study.[4]

History

Prehistoric era

Stone tools, microliths discovered from Chota Nagpur plateau region which are from Mesolithic and Neolithic period.[5] During Neolithic period, agriculture started in South Asia. Several neolithic settlements have found in sites such as Jhusi, Lahuradewa, Mehergarh, Bhirrana, Rakhigarhi, Koldihwa, Chopani Mando and Chirand. At the confluence of Son and North Koel river in Kabra-Kala mound in Palamu district various antiquities, coins and art objects have been found which are from Neolithic to Medieval period and the pot-sherds of Redware, black and red ware, black ware, black slipped ware and NBP ware are from Chalcolithic to late medieval period.[6] During the 2nd millennium BC, the use of Cooper tools had spread in the Chotanagpur plateau region and these find-complexes known as Copper Hoard Culture.[7]

Ancient history

The use of Iron tools and pottery had spread in Chotanagpur plateau region during 1400 BCE according to carbon dating of Iron slag and pottery which have found in Singhbhum district.[8] During the Vedic period, several janapadas emerged in northern India. Parts of western India was dominated by tribes who had a slightly different culture, considered non-Vedic by the mainstream Vedic culture prevailing in the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms. Similarly, there were some tribes in the eastern regions of India considered to be in this category. There were many kingdom existing in the north such as Madra, Salva and in the east such as Kikata, Nishadas who were not following Vedic religion.

Around c. 1200–1000 BCE, Vedic Aryans spread eastward to the fertile western Ganges Plain and adopted iron tools which allowed for clearing of forest and the adoption of a more settled, agricultural way of life. [9][10][11] During this time, the central Ganges Plain dominated by a related but non-Vedic Indo-Aryan culture. The end of the Vedic period witnessed the rise of cities and large states (called mahajanapadas) as well as śramaṇa movements (including Jainism and Buddhism) which challenged the Vedic orthodoxy.[12] According to Bronkhorst, the sramana culture arose in greater Magadha, which was Indo-European, but not Vedic. In this culture, Kshatriyas were placed higher than Brahmins, and it rejected Vedic authority and rituals.[13][14] These Sramana religions did not worship the Vedic deities, practiced some form of asceticism and meditation (jhana) and tended to construct round burial mounds (called stupas in Buddhism).[15] Some parts of Nagpuri speaking region was part of Magadha Mahajanpada.

.png.webp)

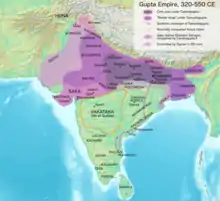

In Mauryan period, this region ruled by a number of states, which were collectively known as the Atavika (forest) states. These states accepted the suzerainty of the Maurya empire during Ashoka's reign (c. 232 BCE). Samudragupta, while marching through the present-day Chotanagpur region, directed the attack against the kingdom of Dakshina Kosala in the Mahanadi valley.[16]

Early modern period (c. 1526 - c. 1858)

During medivial period Nagvanshi and Chero were ruling this region. During region of Akbar, the Mughal invaded Khukhragarh, then Nagvanshi rulers became vassal of Mughals. Nagvanshi were independent during weak Mughal rule. After the Battle of Plassey, the region comes under influence of East India Company. Chero and Nagvanshi ruler then became tributaries to East India company.

Bakhtar Say and Mundal Singh, two landowners from Gumla, fought against the British East India company in 1812 against tax imposition on farmers. British hanged them in Kolkata.[17]

The other princely states in Chota Nagpur Plateau, came within the sphere of influence of the Maratha Empire, but they became tributary States of East India Company as a result of the Anglo-Maratha Wars known as Chota Nagpur Tributary States.[18]

Modern Period (after c. 1850 CE)

The brothers Nilamber and Pitamber were chiefs of Bhogta clan of the Kharwar tribe, who held ancestral jagirs led the revolt against British East India company in 1857.[19]

Thakur Vishwanath Shahdeo and Pandey Ganpat Rai led rebels against British East India Company in 1857 rebellion.[20]Tikait Umrao Singh, Sheikh Bhikhari, Nadir Ali, Jai Mangal Singh played pivotal role in Indian Rebellion of 1857.[21]

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the British East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria.[22]

Post-independence

After Indian independence in 1947, the rulers of the states chose to accede to the Dominion of India. Changbhakar, Jashpur, Koriya, Surguja and Udaipur later became part of Madhya Pradesh state, but Gangpur and Bonai became part of Orissa state, and Kharsawan and Saraikela part of Bihar state.[23] Region under Kings of Nagvansh and Ramgarh became parts of Bihar state.

In November 2000, the new states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand separated from Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, respectively.

Caste and communities

Various communities in Chota Nagpur Plateau traditionally speak the Nagpuri language, including the Ahir, Binjhia, Bhogta, Chik Baraik, Ghasi, Jhora, Kudmi, Kurmi, Kewat, Kharwar,[24] Kumhar, Lohra, Mahli, Nagvanshi, Rautia,[25] Teli and Turi among others.[26]

Language

Nagpuri language/dialect is native to western and central Chota Nagpur plateau region. It is sometimes considered hindi dialect. Nagpuri belongs to Bihari group of Indo-Aryan languages.[27][28] According to professor Keshri Kumar Singh, Nagpuri is descendant of Magadhi Prakrit. According to Dr. Sravan Kumar Goswami, Nagpuri had evolved from Ardhamagadhi Prakrit.[29] Its literary tradition started around the 17th century. It was lingua-franca in the region.[30] The Nagvanshi king Raghunath Shah and King of Ramgarh, Dalel Singh were poet.[31] Hanuman Singh, Jaigovind Mishra, Barju Ram, Ghasiram Mahli and Das Mahli were prominent peot.[32] "Nagvanshavali" written by Beniram Mehta is a historical work in Nagpuri language. Great poet Ghasiram Mahli had written several works including Nag Vanshavali, Durga Saptasati, Barahamasa, Vivha Parichhan etc. There were also great writer like Pradumn Das and Rudra Singh.[33]

Culture

Music and dance

The Nagpuri people have their own styles of dance.[34] Some Nagpuri folk dance are Jhumair, Mardani Jhumair, Janani Jhumair, Domkach, Lahasua, Angnai, faguwa, sanjhi, adhratiya, bhinsariya, Painki etc.[35] Painki is ceremonial martial folk dance performed in marriage and functions.[36]

The musical instruments used in folk music and dance are Dhol, Mandar, Bansi, Nagara, Dhak, Shehnai, Khartal, Narsinga etc.[35] Akhra is important part of Nagpuri culture which is village ground where people dance.[37]

Festival

Karam and Jitia are major festival celebrated among Nagpuri people.[37] Other major festival are Asari, Nawakhani, Sohrai, Fagun etc. Sarna is a place of Sacred grove where village deity resides according to traditional belief, the offering to gaon Khut/gram deoti takes place twice a year before sowing of seeds and harvesting crops for good harvest.

Religion

The deities reverence in nagpuri tradition are Suraj(Solar deity), Chand(lunar deity). Other deities are Gram deoti(village deity), Bar Pahari(hill deity) and Gaurea(Cattle deity) etc. The people worship these deities at home themselves during festivals. In home, rituals performed by head of family and in community festival the rituals performed by village priest "Pahan" and his assistant "Pujar".[38] [39][36] The Nagpuri religious tradition is based on local folk tradition and is non-vedic Indo-Aryan tradition which was prevailed in Magadha region. According to June McDaniel, folk hinduism is based on local traditions and cults of local deities and is the oldest, non-literate system. It is pre-vedic tradition extending back to prehistoric times, or before written of Vedas.[40]

According to ancient texts several tribes were living in border of Brahmanical India including Magadha, Madra, Salva, Kikata, Nishadas and Shakya, the clan of Gautama Buddha were following non-vedic culture.[41]

Chotangpur region was outside pale of Aryavarta and local people have been following non-vedic Indo-Aryan culture since Chalcolithic period such as worship of tree spirit, nagas etc which has been described as non-vedic practice by ancient texts. The Vedic religion and Brahmanism influence reached in the region after arrival of Brahmin perhaps during post Mauryan period. The Nagvanshi rulers constructed several temples during their reign and invited Brahmin from different parts of the country for priestly duty.[42]

Marriage tradition

Nagpuri marriage is unique. Prior to marriage, the boy’s relatives go to girl’s home to see and negotiate for marriage and token amount is paid by the boy’s family to the girl’s family as part of the marriage expenses called damgani.

The process of marriage starts with giving of Sari by boy's family to girl's family. Damgani, panbandhi, matikoran (worship of gramadevata), madwa and dalhardi, nahchhur, amba biha, painkotan, baraat, pairghani, sindoor dan (Vermilion giving), harin marek (hunting deer), chuman (giving gifts), etc are the activities and rituals of marriage accompanied by music of Nagara, Dhak and Shehnai played by traditionally musicians of Ghasi community. There are different songs for different marriage rituals. Domkach, Pairghani(welcome ceremony) dance performed during marriage. Wedding performed by thakur/Nai (barber) and the village priest called pahan in matikoran. Traditionally nagpuri wedding conducted without a Brahmin priest.[38]

Notable people

- Jay Prakash Singh Bhogta, M.L.A from Chatra

- Satyanand Bhogta, Former Agriculture minister of Jharkhand

- Ram Tahal Choudhary, former Member of Parliament

- Ganesh Ganjhu, M.L.A from Simaria

- Deepika Kumari, International Archer

- Ghasiram Mahli, Poet

- Mukund Nayak, folk artist

- Nandlal Nayak, Music composer

- Nikki Pradhan, Field hockey player

- Pushpa Pradhan, Field hockey player

- Vimla Pradhan, Former Social welfare and tourism minister of Jharkhand

- Dhiraj Prasad Sahu, MP of Rajya sabha

- Shiv Prasad Sahu, former Member of Parliament

- Bakhtar Say, freedom fighter

- Raghunath Shah, Nagvanshi king and poet

- Ani Nath Shahdeo, King of Barkagarh

- Gopal Sharan Nath Shahdeo, Prince and former M.L.A from Hatia

- Lal Chintamani Sharan Nath Shahdeo, Last Nagvanshi king

- Lal Pingley Nath Shahdeo, Jurist and Political activist

- Lal Ranvijay Nath Shahdeo, Lawyer, writer, poet and political activist

- Lal Vijay Shahdeo, director

- Vishwanath Shahdeo, Freedom fighter in 1857 rebellion

- Mundal Singh, freedom fighter

- Rameswar Teli, Politician from Assam

Notes

References

- "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues - 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Sadri". Ethnologue.

- "Sadani / Sadri". Southasiabibliography.de. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Barz, Gregory F.; Cooley, Timothy J. (9 September 2008). Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology. ISBN 9780199886708.

- periods, India-Pre- historic and Proto-historic (4 November 2016). India – Pre- historic and Proto-historic periods. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 9788123023458. Retrieved 8 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- "KABRA – KALA". www.asiranchi.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- Paul Yule, Addenda to "The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation", Man and Environment 26.2, 2002, 117–120 http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/savifadok/volltexte/2009/510/.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131711200. Retrieved 8 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- Stein 2010, p. 50.

- Witzel 1995, p. 3-5.

- Samuel 2010, p. 49-52.

- Flood 1996, p. 82.

- Bronkhorst 2007.

- Long 2013, p. chapter II.

- Bronkorst, J; Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India (2007), p. 3

- Sharma, Tej Ram (1978). Personal and Geographical Names in the Gupta Inscriptions. Concept Publishing Company. p. 258.

- "Raghubar honours Simdega patriots". timesofindia. 18 April 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- http://www.southasiaarchive.com/Content/sarf.100009/231191

- "History". latehar.nic.in.

- "cm pays tribute thakur vishwanath sahdeo birth anniversary". avenuemail. 13 August 2017.

- "JPCC remembers freedom fighters Tikait Umrao Singh, Sheikh Bhikari". webindia123. 8 January 2016.

- Kaul, Chandrika. "From Empire to Independence: The British Raj in India 1858–1947". Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Eastern States Agency. List of ruling chiefs & leading personages Delhi: Agent to Governor-General, Eastern States, 1936

- Minz, Diwakar; Hansda, Delo Mai (2010). Encyclopaedia of Scheduled Tribes in Jharkhand. ISBN 9788178351216.

- People of India Bihar Volume XVI Part Two edited by S Gopal & Hetukar Jha pages 945 to 947 Seagull Books

- "1 Paper for 3 rd SCONLI 2008 (JNU, New Delhi) Comparative study of Nagpuri Spoken by Chik-Baraik & Oraon's of Jharkhand Sunil Baraik Senior Research Fellow". slideplayer.com.

- Wynne, Alexander (1 July 2011). "Review of Bronkhorst, Johannes, Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India". H-net.org. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Lal, Mohan (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. ISBN 9788126012213.

- Ranjan, Manish (19 August 2002). Jharkhand Samanya Gyan. ISBN 9789351867982.

- Brass Paul R., The Politics of India Since Independence, Cambridge University Press, pp. 183

- "gaint new chapter for nagpuri poetry". telegraphindia. 5 November 2012.

- "नागपुरी राग-रागिनियों को संरक्षित कर रहे महावीर नायक". prabhatkhabar. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Ranjan, Manish (January 2016). Jharkhand Samanya Gyan. ISBN 9789351866848.

- Sharan, Arya (1 June 2017). "Colours of culture blossom at Nagpuri dance workshop". The Daily Pioneer. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Out of the Dark". democratic world. 7 June 2014.

- "बख्तर साय मुंडल सिंह के बताए राह पर चलें". bhaskar. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "talk on nagpuri folk music at ignca". daily Pioneer. 7 November 2018.

- "Culture and Tradition of Chik Baraik Community". chikbaraik.org.

- Minz, Diwakar; Hansda, Delo Mai (2010). Chik Baraik. ISBN 9788178351216. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- June McDaniel "Hinduism", in John Corrigan, The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Emotion, (2007) Oxford University Press, 544 pages, pp. 52–53 ISBN 0-19-517021-0

- Levman, Bryan Geoffrey (2013). "Cultural Remnants of the Indigenous Peoples in the Buddhist Scriptures", Buddhist Studies Review 30 (2), 145-180. ISSN (online) 1747-9681.

- Ranjan, Manish (19 August 2002). Jharkhand Samanya Gyan. ISBN 9789351867982. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nagpuri people. |