Natalia Negru

Natalia Negru (December 5, 1882 – September 2, 1962) was a Romanian poet and prose writer. Although her literary contributions were relatively minor, she is noted for being at the center of a love triangle involving her first husband, Ștefan Octavian Iosif, and her second, Dimitrie Anghel. The men were close friends, but Anghel seduced her, she divorced Iosif, who died of his grief, and then Anghel shot himself during a quarrel with her, dying of the wound two weeks later. Two years after Anghel's death, her daughter with Iosif was killed by a German bomb during World War I. She lived for four and a half decades after these turbulent events, in relatively uneventful fashion.

Natalia Negru | |

|---|---|

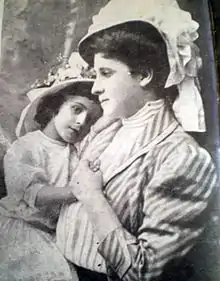

Negru with her daughter Corina before c.1916 | |

| Born | December 5, 1882 Buciumeni, Tecuci County, Romania |

| Died | September 2, 1962 (aged 79) Tecuci, Galați County |

| Pen name | Natalia Iosif |

| Alma mater | University of Bucharest (1907) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Corina Octavian Iosif (died 1916) |

Biography

Early life and first marriage

Born in Buciumeni, Tecuci County, her parents were Avram Negru, a teacher, and his wife Elena (née Dumitrescu).[1] Negru attended primary school in Galați, where her father worked, and high school in Bucharest. She enrolled in the literature and philosophy faculty of the University of Bucharest in 1901, graduating in 1907. Fond of reading in the University Foundation Library, she met its caretaker, the published poet Ștefan Octavian Iosif, in 1903. A grateful Iosif asked her for poems, one of which he published in a prominent position in Sămănătorul. In order to attract his attention, she presented an essay about one of his poems to her class.[2] The couple married in July 1904; the three-day wedding took place at Tecucel on the outskirts of Tecuci, where her father had built her a house and granted her ten hectares of vineyards. Guests included Nicolae Iorga and Mihail Sadoveanu, who wrote accounts of the festivities.[3] Their daughter Corina was born a year later.[2]

Dimitrie Anghel, Iosif's closest friend and a collaborator on poems, visited the family home almost daily and fell in love with Natalia.[2] Iosif broke with Anghel in spring 1910, and became alienated from his wife that summer.[3] Anghel eventually convinced her to move in with him,[2] and she sued for divorce in November. She won the case the following June because two letters from Iosif proved he had left their home. In December, after suing but before the divorce was granted, she traveled to Paris for health reasons and later invited Iosif to spend a month together, presumably seeking a reconciliation. He declined, and Anghel went instead.[3] Devastated by the betrayal of the woman he idolized and who was the inspiration behind most of his later work, as well as of his best friend, Iosif died of a stroke in June 1913.[2]

Second marriage

Negru and Anghel married in November 1911; the union created hostility around them, especially in the literary circles that valued Iosif's poetry and his delicate temperament. The ostracizing atmosphere worsened after his death. Meanwhile, the marriage was deteriorating, with the temperamental and jealous Anghel locking up his wife for days at a time.[2] The couple had frequent scenes involving screams, explosive emotions and sudden reconciliations; on at least one occasion, Anghel broke down a door and embraced his wife's feet in tears.[4]

One day in autumn 1914, a key fell out of his pocket, and she accused him of using it for romantic encounters in a hotel room. He convinced her it was for office use, but tension remained between the two. Several days later, while visiting her parents, she renewed the attack and announced she was going home. Anghel threatened to shoot her if she did not calm down; his wife believed he was joking, and continued toward the door. He pulled out his revolver and, intending to frighten her, fired toward a window. The bullet hit the metal frame of a bed and ricocheted, lightly wounding Negru. She fell to the ground; believing he had killed her, Anghel fired into his chest. The wound became infected and he died of sepsis two weeks later. At the funeral, an unknown female reportedly shouted, "You miserable woman, who kill all the country's great people!"[2]

For a long time afterwards, Negru faced public opprobrium that sometimes took hysterical turns. George Călinescu viewed her as a femme fatale without blame of her own. Her third marriage, to theologian Ioan Gheorghe Savin, appears to have been tranquil however they separated after Savin married Lucia Avramescu.[4][5]

Subsequent life and writings

In September 1916, shortly after Romania entered World War I, her daughter was killed by shrapnel from a bomb dropped by a Zeppelin.[2] With the Central Powers rapidly approaching Bucharest, she moved to Tecucel, living there exclusively from the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s. After 1945, she moved seasonally between Tecucel and a town house in Tecuci, where she died in 1962.[3] The Tecuci house, which dates to the end of the 19th century, is listed as a historic monument by Romania's Culture Ministry.[6]

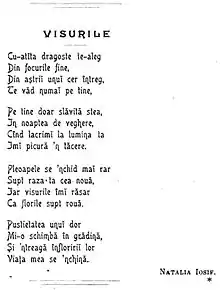

She signed her early writings Natalia Iosif. Negru's work was published in Cumpăna, Junimea literară, Minerva literară ilustrată and Profiluri feminine, where she wrote the literature column. She was a founding member of the Romanian Writers' Society. Her output includes poems collected in the book O primăvară (1909), a dramatic poem (Legenda, 1921), a dramatized legend (Califul Barză, 1921) and two autobiographical novels (Mărturisiri, 1913; Helianta, 1921).[1] The latter represented Negru's attempt to tell her side of the love triangle story, and may have been an attempt to exorcise a guilty conscience, or at least one held guilty by others.[4] She published translations of Hans Christian Andersen, Gustave Aimard, André Theuriet, Nicholas Wiseman (Fabiola) and Prosper Mérimée (Colomba).[1]

Critical opinion of Negru's poetry has tended to be negative. Eugen Lovinescu placed her "in the unoriginality competition of Sămănătorist poetesses", noting she "concocted little sentimental exuberances" out of typical and already stale Sămănătorist material. Constantin Ciopraga found the poems in O primăvară "saturated with idyllism.... easily confused with analogous productions of the period". Commenting on the same work, Alexandru Piru found that "one can remember nothing of her elegies [there]". A slightly more appreciative Victor Durnea finds "a certain lyrical, ingenuous sensibility" that can be "glimpsed.... in the recovery of certain childhood and adolescent memories". However, he finds her prose more redeeming. Alex. Cistelecan labels the poems "childish", speculating they may date to Negru's high school days.[4]

Notes

- Aurel Sasu (ed.), Dicționarul biografic al literaturii române, vol. II, p. 205. Pitești: Editura Paralela 45, 2004. ISBN 973-697-758-7

- (in Romanian) Marius Mototolea, "Povestea tragicului triunghi amoros din istoria literaturii române", Adevărul, February 8, 2013

- (in Romanian) Bogdan Nistor, "'Femeia fatală': Natalia Negru a stat la originea morții a doi importanți scriitori români", Adevărul, February 8, 2013

- (in Romanian) Alex. Cistelecan, "Natalia, femeia-drog", in Revista Limba Română, Nr. 11–12/2009

- (in Romanian) Iurie Colesnic, "Unul dintre intelectualii care a dat culoare Chișinăului intervalic", Timpul, September 9, 2013

- (in Romanian) Lista Monumentelor Istorice 2010: Județul Galați