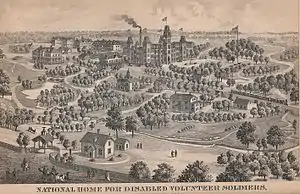

National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

The National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was established on March 3, 1865, in the United States by Congress to provide care for volunteer soldiers who had been disabled through loss of limb, wounds, disease, or injury during service in the Union forces in the American Civil War. Initially, the Asylum, later called the Home, was planned to have three branches: in the Northeast, in the central area north of the Ohio River, and in what was then considered the Northwest, the present upper Midwest.

The Board of Managers, charged with governance of the Home, added seven more branches between 1870 and 1907 as broader eligibility requirements allowed more veterans to apply for admission. The effects of World War I, which resulted in a new veteran population of over five million men and women, brought dramatic changes to the National Home and all other governmental agencies responsible for veterans' benefits. In 1930 the Veterans Administration was established, to consolidate all veterans' programs into a single Federal agency. The several wars since then in the 20th and 21st centuries have resulted in more veterans needing services.

Beginning of the National Home

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was originally called the National Asylum in the legislation approved by Congress and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in March 1865. The term "asylum" was used in the 19th century for institutions caring for dependent members of society, such as the insane and the poor, who were thought to temporarily suffer from conditions that could be cured or corrected.[1] But, the term had some negative connotations. In January 1873, the Board of Managers gained approval of the name, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

From the Revolutionary War through the Civil War, the small number of veterans of American wars had three sources of assistance from the Federal government. The government offered land grants to veterans as compensation for their service, particularly following the Revolutionary War, when it used the land grant system to develop unsettled territories of the new nation. In 1833, the Federal government established the Bureau of Pensions, which made small cash payments to veterans. The low numbers of the veteran population and the more attractive offer of free land kept the pension system relatively small until after the Civil War.

In 1811 the United States Navy was authorized by Congress to establish a permanent shelter for its veterans; construction was started in 1827. The United States Sailors' Home, located in Philadelphia as part of the Navy Yard, was opened in 1833.[2] In 1827, Secretary of War James Barbour suggested a similar institution for the Army, but Congressional lack of interest and funding meant such a project was delayed.[3]

In 1851, legislation introduced by Jefferson Davis, senator from Mississippi and former secretary of war, was enacted by Congress. It appropriated funds for construction of the United States Soldiers’ Home. The Soldiers’ Home was open to all men who were regular or volunteer members of the army with 20 years' service and who had contributed to the home's support through pay withdrawals.

When the Soldiers’ Home was being organized in 1851 and 1852, it was intended to have at least four branches. Its organization and administration were based on the army’s command structure and staffed with regular army officers. The Soldiers’ Home was managed by a board of commissioners, although drawn from army officers; each branch had a governor, deputy governor, and secretary-treasure; the members were organized into companies and the daily routine followed the military schedule; all members wore uniforms; and workshops were provided for members wanting or required to work.[4] When the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was being organized in 1866, the National Soldiers’ Home assisted the asylum’s board by explaining its regulations and offering suggestions.[5]

The Civil War was the first event in the history of the United States considered to be national in the scale of citizen involvement, and in its effects on the daily lives of people communities in both the North and the South. The Civil War was a war of volunteers and draftees, both military and civilian. Very early in the war, it became clear to social leaders in the North that new programs were required to deliver medical care to the wounded beyond what was available through the official military structure.

The leading civilian organization was the United States Sanitary Commission; it secured permission from President Lincoln in the summer of 1861 to deliver medical supplies to the battle front, build field hospitals staffed with volunteer nurses (mostly women), and raise funds to support the commission’s programs.[6] As the war continued, civilian leaders began to address the issue of caring for the numerous veterans who would require assistance once the war ended. Members of the Sanitary Commission favored the pension system rather than permanent institutional care for the disabled veteran; the commission feared that a permanent institution would become a poorhouse for veterans.[7] Other groups favored as strongly the establishment of a soldiers’ asylum, to ensure provision of quality care. The groups gathered information on European military asylums, particularly the Invalides in Paris. They tended to find evidence to support their opinions on either side of the concept of a soldiers' asylum.[8]

When President Lincoln signed legislation creating the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in March 1865, the nation was in a period of heightened emotional response to the approaching peace. The victory of the Union was seen as the triumph of the nation. The creation of a national institution to serve the veterans was an affirmation of that national victory. When the institution was established, supporters likely had a limited awareness of the potential need among future veterans. But, more than 2,000,000 men served in the Union Army, a third of the white men of military age (13 to 43 years old in 1860).[9] If the number of men disabled in service equaled a sixth of the soldiers who died in the war, the number eligible for admission to the National Asylum would have been more than 300,000.

Board of Managers (1866–1916)

It took time for the new institution to be organized, including design and construction of the building. The original corporation could not secure a quorum for a year after being authorized. In March 1866, Congress passed new legislation to replace the 100-member corporation with a twelve-member board of managers, a more manageable group. Still, they had to select the sites, arrange supervision of construction projects, and designate local officials while serving as unpaid volunteers of an independent Federal agency. The managers of the Asylum looked to past models and local efforts to guide the creation of the institution.

The Board of Managers of the National Asylum met for the first time in Washington, D.C. on May 16, 1866. Their first priority was the selection of sites for the three branches of the national institution, based on geographic distribution. They established criteria for site evaluation: a healthy site with fresh air and ample water supply, located 3 to 5 miles (8.0 km) from a city, and consisting of a tract of at least 200 acres (0.81 km2), connected to the city by a railroad.[10] The Board issued a bulletin to newspapers and to governors of the northern states requesting proposals for sites to be donated or sold for use by the branches. Proposals were due before July 12. In addition, the Board advertised for plans, specifications, and estimates for the construction of asylum buildings.

At the September 1866 Board meeting, General Benjamin Butler, the President of the Board, proposed the purchase of a bankrupt resort at Togus, Maine, near Augusta, as the eastern branch of the Asylum. In regards to a Milwaukee location or a northwestern branch, the Board directed that an Executive Committee visit the city to select a site. Possible locations for a central branch were discussed.

At the December 7, 1866 meeting of the Board, the Executive Committee announced its approval of a Milwaukee location. The Board directed them to return to Milwaukee to purchase a site and arrange for the construction of asylum buildings, as well as the transfer of veterans currently housed in the Wisconsin Soldiers' Home in Milwaukee, operated by the Lady Managers of the Home Society.[11] At the same meeting, the Board approved the purchase of the Togus site. Veterans had already been moved into the former hotel on the site in November 1866. The Central Branch location in Dayton, Ohio, was not selected until September 1867.[12]

The selection of the sites for the three branches was based on three motivations: practical, political and economic. First, the Board needed sites ready to be used immediately before the second winter after the war, and before the time of the November 1866 elections. The Togus site, having been a resort, had a sufficient number of buildings appropriate for housing the disabled veterans. Choosing Dayton as the Central Branch site satisfied the powerful Ohio faction in Congress, as well as the numerous Union generals from Ohio, particularly William Tecumseh Sherman. Locating the Northwestern Branch at Milwaukee resulted in the Board of Managers gaining a large cash donation from the Ladies Managers, enabling them both to purchase a site and have funds left to begin construction.

As the first buildings at the Northwestern Branch were being completed in 1867–1869, the Board of Managers concentrated building efforts at the Central Branch, and in rebuilding facilities at the Eastern Branch, which had been destroyed by fire in 1868. Even though membership had increased in the first few years the Asylum was open, the Board had felt membership would soon begin to decline. The Board based this on the belief that any veteran who needed the Asylum had already entered it and that, as members regained their health or learned new work skills, they would leave the Asylum. In 1868, the Board adopted a resolution that limited the number of branches to the three existing ones.[13] Problems with construction of the Main Building at the Northwestern Branch, and concern over the harsh winters at both the Northwestern and Eastern branches, led the Board to open a fourth branch in 1870 at a site in a warmer climate; it had existing buildings available for immediate use. In addition, an increasing number of veterans applied for services.

The Southern Branch of the National Asylum was established in October 1870, with the Board's purchase of the Chesapeake Female College at Hampton, Virginia.[14] What became the main building of this new branch was built in 1854 and used as the principal facility of the college. The building was used as a hospital for both Union and Confederate troops. In the economic downturn following the Civil War, the women's college did not reopen. Acquisition of the property by the National Home followed the precedent four years earlier of the purchase of the Togus resort.

The Southern Branch was founded to provide a facility in a milder climate for the benefit of older veterans, to house Southern black members whom the board believed would be more accustomed to a southern location, and to be associated with Fort Monroe, adjacent to the new branch site. The Federal troops at Fort Monroe and Union veterans at the Southern Branch would establish a strong Union presence near the strategic city of Newport News in the former Confederate state of Virginia.

On January 23, 1873, Congress passed a resolution changing the name of the institution to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, reflecting the increasing permanence of the institution and its membership. In 1875, the Board's report to Congress stressed the need for construction of larger accommodations as quickly as possible.[15] The Broad projected an eventual decline in the population as of the early 1870s, due to an increase in death rate with aging, but also said that it expected more aging veterans to apply for admission in the late 1870s and early 1880s. In 1875, major construction projects were started at the four branches, in part to provide more housing, but also to provide more hospital facilities to meet the changing medical needs of the members.

Considering the ages for Civil War participants ranged from 13 to 43 years in 1860, the Home could have expected continuing admissions well into the 20th century. The Board indicated a new understanding of the population makeup when it recommended that Congress change the eligibility requirements for admission to the Home by allowing benefits to all destitute soldiers unable to earn a living, without having to trace their disabilities to their military service.[16] The Board realized that denying benefits to this large group of veterans meant their only recourse was the poor house.

In 1883, the Board, recognizing the changes the Home would face with increased membership and increased medical needs of the members, conceded that an "institution like the National Home must in time become an enormous hospital." It concluded that all new buildings for the Home must be planned with that in mind.[17] As a result, the Board asked for Congressional appropriations to enlarge the hospital at the Central Branch and to build a new hospital at the Southern Branch. At the September 1883 Board meeting, the managers considered asking Congress for the transfer of Fort Riley, Kansas, to the Home as a new facility. They understood the fort was likely to be abandoned since the end of most of the Indian Wars, and it would be easily adaptable to Home use. The Board tabled the motion, but the issue of establishing additional branches of the National Home had been raised.[18]

On July 5, 1884, Congress approved the Board’s recommendation to change the eligibility requirements for admission, allowing any veterans disabled by old age or disease to apply without having to prove a service-related disability. In effect, the Federal government assumed responsibility of providing care for the aged veterans; what had been established as a temporary asylum for the disabled in 1866, had become a permanent home for the elderly. This legislation provided for expansion of the National Home by authorizing branches to be established west of the Mississippi and on the Pacific Coast.[19]

With the loosening of restrictions, the Home rapidly had an increase of 12% in membership, but it had not gained additional funding from Congress. The Board returned to Congress with a request for deficiency funding, arguing that the Home could either go into debt, which was illegal under its organic law, or it would have to discharge a large number of members to save on expenses.[20]

Expansion at the four original branches proceeded more slowly after 1884. The 1884 Board of Surgeons Report recommended that the Central Branch was already too large and should not be expanded; the severe climate at the Eastern and Northwestern branches should limit their growth; and the Southern branch should not be allowed to grow to more than 1500–2000 members. The surgeons suggested that new branches were a better solution than enlarging the older ones. They also recommended that certain diseases would benefit from treatment at the various branches. The establishment of new branches in the west and one the Pacific coast limited the expansion of the older branches.

In September 1884, the Board selected Leavenworth, Kansas, as a new location, contingent on the city donating a tract of 640 acres (2.6 km2) and $50,000 to provide for "ornamentation"; the city accepted in April 1885.[20] At the same meeting, the Board took under consideration the establishment of a Pacific Branch; it opened in Santa Monica, California in January 1888. Even with the creation of two new branches, the Board realized that membership would continue to increase; it proposed four alternatives to manage the needs.[21] Additional branches could be established; existing branches could be enlarged; states could be encouraged to erect state soldiers' homes through partial funding from the Federal government; and financial relief to veterans outside the Home system could be increased.

Congress established a new Home branch in Grant County, Indiana, on March 23, 1888, with an initial appropriation of $200,000, based on the county residents' providing natural gas supply sufficient for the heating and lighting of the facility. The site selected was near Marion, Indiana, and the new facility was called the Marion Branch.[22] The Marion Branch was the seventh of ten homes and one sanatorium that were built between 1867 and 1902. These homes were primarily intended to provide shelter for the veterans. The homes gradually developed as complete planned communities, with kitchens, gardens and facilities for livestock, designed to be nearly self-sufficient. It appears that these homes were the first non-religious planned communities in the country.

Additionally, Congress passed legislation to provide $100 annually for every veteran eligible for the National Home who was housed in a state soldiers' home. In 1895, the Indiana legislature authorized the establishment of a state soldiers’ home, which was built in West Lafayette, Indiana.

The National Home continued to face problems of overcrowding and the need for more specialized medical care. In 1898, Congress approved an eighth branch, to be established at Danville, Illinois. The Mountain Branch was established in 1903 near Johnson City, Tennessee. The last of the National Home facilities was established as the Battle Mountain Sanitariumt at Hot Springs, South Dakota, in 1907. It was not a full-service branch, but a specialized institution open to members from any of the nine branches who were suffering from rheumatism or tuberculosis. Neither disease could be cured at the time, but patients were believed to benefit from the dry air prevalent at that location. Between 1900 and 1910, the Board of Managers were directed most of their attention to developing these three new branches.

1916–1930

In 1916, the Board of Managers believed that membership had begun to decline, due to aging and deaths of veterans. But, on April 6, 1917, the United States entered World War I. By the time of the armistice on November 11, 1918, almost five million Americans had entered the armed forces. On October 6, 1917, an amendment to the War Risk Insurance Act, originally enacted in 1914 to insure American ships and cargo against risks of war, extended eligibility for National Home membership to all troops serving in the “German War.” Most importantly, it provided that all veterans were entitled to medical, surgical and hospital care by the federal government.

Prior to the 1917 amendment, the only veterans entitled to such medical care were members of the National Home who had access to the Home hospitals. All other veterans were dependent on civilian medical services. The 1917 amendment meant that all veterans were eligible for the same medical care as the members of the National Home. Existing hospital facilities at the ten Home branches were insufficient to care for the potentially high number of World War I veterans needing medical care.

In 1919, the responsibility for veterans’ services was distributed among several agencies: the United States Public Health Service (PHS) took over the provision of medical and hospital services; the Federal Board for Vocational Rehabilitation organized rehabilitation programs; and the War Risk Insurance Bureau managed compensation and insurance payouts.[23] The burden on PHS government hospitals was so great that the Service began to contract with private hospitals to provide health care for veterans.

On March 4, 1921, in response to the need for veterans' hospitals, Congress appropriated funds to construct additional hospitals for veterans covered by the War Risk Insurance Act amendment. In addition, in 1926 Congress required the Bureau of War Risk Insurance to make allotments to the National Home to fund alterations or improvement to existing Home facilities to care for beneficiaries.[24]

Immediately after the war, the National Home took actions to accommodate the large number of returning veterans:

- 1) transformed facilities of two branches into hospitals and classified them for specialized care (Marion for neuropsychiatric cases and Mountain for tuberculosis, which were the two classes of illness with the highest numbers of patients),

- 2) modernized existing facilities and established tuberculosis wards (Central and Pacific); and

- 3) built entirely new hospitals (Northwestern), using funding from the Treasury Department.[25]

In August 1921, Congress established the Veterans Bureau to manage all veterans’ benefits. On April 29, 1922, this agency assumed responsibility for fifty-seven veterans’ hospitals operated by the Public Health Service, as well as nine under construction by the Treasury Department.[26]

The participation of African Americans in World War I and issues of racism in US society added to the complexity of caring for veterans. African Americans pressed their case to the federal government, feeling that their service had created an obligation by the government to help them in the war's aftermath. African Americans had difficulty gaining medical care, especially in the South. The federal government authorized construction of what was originally called the "Tuskegee Home", now the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center, on land adjacent to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Opened in 1923 with 600 beds, it was intended to serve the 300,000 African-American veterans in the South. The complex eventually had 27 buildings, and more than 2300 beds by 1973.[27][28]

By 1926, the Board began to see a new trend in veterans’ use of the National Home. For the most part, the World War I veterans were receiving medical treatment and returning to civilian life, rather than entering the domiciliary program for the Home.[29] The Board noted that hospital care costs were almost three times the cost of domiciliary care, and it required large capital investments in hospitals, medical equipment, and professional staff. By 1928, the Board concluded that it was not capable of managing the National Home as a national medical service.[30]

In June 1929, the president of the Board of Managers was appointed to the Federal Commission for Consideration of Government Activities Dealing with Veterans’ Matters. The Commission recommended the founding of the Veterans Administration as a federal agency.

On July 21, 1930, the Veterans Bureau, the Bureau of Pensions, and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers were consolidated into the Veterans Administration. The National Home was designated the “Home Service.” In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt’s relief program during the Great Depression put a temporary hold on funding for Veterans Administration construction projects, in favor of projects that could quickly put people to work and be completed more rapidly. Two years later, in August 1935, plans were announced for a $20,000,000 building program for the Veterans Administration. Several of the former National Home branches received funding for new medical treatment buildings, domiciliaries, storage buildings, and garages for staff quarters.

On December 7, 1941, another war brought a new period of change to the former National Home. More citizens were drafted for military service. To meet the demand for services after World War II, and later the Korean and Vietnam wars, the former branches of the National Home were expanded and adapted to serve veterans. To ensure high-quality development and training for personnel, in the postwar years the Veterans Administration and its hospital officials worked to establish medical residency programs at veterans hospitals, accredited through collaboration with local and regional universities.

During its life, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was also known "officially" as the National Military Home and colloquially as the Old Soldiers Home. The formal organizational name was not changed by statute. But, the mailing address for most branches became "National Military Home," in the appropriate city and state. In the early days, the designation of "old soldier" had no bearing on an individual veteran's age. It was used for all veterans.

Meals

Breakfast meals included ham, sausage, corned beef hash, baked beans with pork, beef fricassee with hominy, potatoes. bread, butterine. Dinners might include string beans, lima beans, dried peas, pickles, pies, roast mutton, soups like vegetable or bean, roast beef and crackers. Supper would be a light fare like stewed dried fruits, watermelons, sugar cookies, tea, fresh berries, corn meal or rolled oats with syrup, cheese and biscuits.[31]

The quantities of food required were enormous, including 2,800 pounds of ham for the Sunday breakfast, or 2,950 pounds of sausage. 1,250 pies were eaten for dinner, 800 pounds of bread at each meal, and so forth. Preparing these meals required 126 cooks, 44 bakers, 18 butchers, 22 bread cutters, along with farm hands, dishwashers, servers and gardeners.[31]

Branches of the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

| Home | Location | Date Established |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Branch | Togus, ME | 1866 |

| Central Branch | Dayton, OH | 1867 |

| Northwestern Branch | Milwaukee, WI | 1867 |

| Southern Branch | Hampton, VA | 1870 |

| Western Branch | Leavenworth, KS | 1885 |

| Pacific Branch | Sawtelle, Los Angeles, CA | 1888 |

| Marion Branch | Marion, IN | 1888 |

| Roseburg Branch | Roseburg, OR | 1894 |

| Danville Branch | Danville, IL | 1898 |

| Mountain Branch | Johnson City, TN | 1903 |

| Battle Mountain Sanitarium | Hot Springs, SD | 1907 |

| Tuskegee Home | Tuskegee, AL | 1923[27] |

| Bath Branch | Bath, NY | 1929 |

| St. Petersburg Home | St. Petersburg, FL | 1930 |

References

- Rothman, David J, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic, Boston, MA 1971, pg. 131-13

- Cetina, Judith Gladys, A History of Veterans' Homes in the United States, 1811-1930, Ph.D. Diss., Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 1977, pg. 30-39

- Cetina (1977), History of Veterans' Homes, pg. 39-53

- Paul R. Goode, The United States Soldiers' Home, Richmond, VA 1957, pg. 24-26, pg. 45-46

- Goode, Soldiers' Home, pg. 99

- For the work of the Sanitary Commission: William Q. Maxwell, Lincoln's Fifth Wheel: The Political History of the United States Sanitary Commission, London, 1956

- Robert Bremner, The Public Good: Philanthropy and Welfare in the Civil War Era

- Cetina, History of Veterans' Homes, pg. 61-72

- Maris A. Vinovskis, "Have Social Historians Lost the Civil War? Some Preliminary Demographic Speculations," Toward A Social History of the American Civil War, Cambridge, 1990, pg. 9

- Board of Managers of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Proceedings, May 16, 1866, p.2

- Board of Managers of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Proceedings, December 7, 1866, p.7

- Dayton’s soldiers’ home was among the country’s first to care for veterans, by Lisa Powell, staff writer, Dayton Daily News, 24 May 2019. Accessed March 2020.

- Board of Managers of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Proceedings, March 12, 1868, p. 21

- Board of Managers of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Proceedings, October 28, 1870, pg. 75

- Board of Managers of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Annual Report for 1875, pgs 4–5

- Board of Managers, Annual Report for 1882, pg 3

- Board of Managers, Annual Report for 1883, pg 3

- Board of Managers, Annual Report for 1883, pg 25 22.

- Cetina, History of Veterans' Homes, pg. 183, 196–197

- Board of Managers, Annual Report for 1884, pg 5

- Cetina, History of Veterans' Homes, pg. 186, citing the Board of Managers Annual Report for 1887, pg. 3

- Board of Managers Proceedings for 1888, pg 198

- Gustavus Weber and Laurence Schmeckebier, The Veterans Administration, Washington D.C., 1934, pg. 4

- Board of Managers Proceedings, December 6, 1926, pg. 443

- Cetina, History of Veterans' Homes, pg. 378-379

- Weber and Schmeckebler, Veterans Administration, pg. 16-17

- "Tuskegee VA Medical Center Celebrates 85 Years of Service", press release, Central Alabama Veterans Health Care System (CAVHCS), (accessed 6 April 2010)

- "VA Hospital began with 25 beds, now has 2,307", The Tuskegee News, 8 February 1973, accessed 6 April 2010.

- Board of Managers Proceedings, March 20, 1928, pg. 7

- Robert M. Taylor, Jr., Indiana: An Interpretation, New York, 1947, pg. 76-78

- The New England Magazine, Volume 22. Warren F. Kellogg. 1900. p. 292.

- Plante, Trevor K. "The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers." Prologue Magazine, Spring 2004. 36(1). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2004/spring/soldiers-home.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. |