Neoteny in humans

Neoteny in humans is the retention of juvenile features well into adulthood. This trend is greatly amplified in humans especially when compared to non-human primates. Adult humans more closely resemble the infants of gorillas and chimpanzees than the adults. Neotenic features of the head include the globular skull;[1] thinness of skull bones;[2] the reduction of the brow ridge;[3] the large brain;[3] the flattened[3] and broadened face;[2] the hairless face;[4] hair on (top of) the head;[1] larger eyes;[5] ear shape;[1] small nose;[4] small teeth;[3] and the small maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw).[3]

Neoteny of the human body is indicated by glabrousness (hairless body).[3] Neoteny of the genitals is marked by the absence of a baculum (penis bone);[1] the presence of a hymen;[1] and the forward-facing vagina.[1] Neoteny in humans is further indicated by the limbs and body posture, with the limbs proportionately short compared to torso length;[2] longer leg than arm length;[6] the structure of the foot;[1] and the upright stance.[7][8]

Humans also retain a plasticity of behavior that is generally found among animals only in the young. The emphasis on learned, rather than inherited, behavior requires the human brain to remain receptive much longer. These neotenic changes may have disparate roots. Some may have been brought about by sexual selection in human evolution. In turn, they may have permitted the development of human capacities such as emotional communication. However, humans also have relatively large noses and long legs, both peramorphic (not neotenic) traits, though said peramorphic traits that separate modern humans from extant chimpanzees were present in Homo erectus to an even higher degree than in Homo sapiens, keeping general neoteny valid for the erectus to sapiens transition although there were perimorphic changes separating erectus from even earlier hominins such as most Australopithecus.[9] Later research shows that some species of Australopithecus, including Australopithecus sediba, had the non-neotenic traits of Homo erectus to at least the same extent which separate them from other Australopithecus, making it possible that general neoteny applies throughout the evolution of the genus Homo depending on what species of Australopithecus that Homo descended from. The type specimen of Sediba had these non-neotenic traits, despite being a juvenile, suggesting that the adults may have been less neotenic in these regards than any Homo erectus or other Homo.[10]

Neoteny and Heterochrony

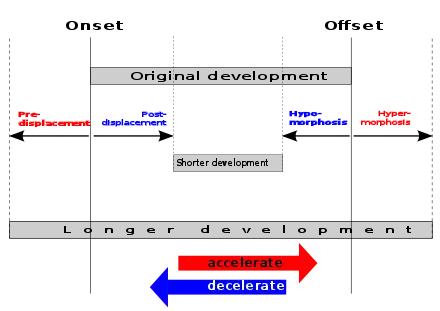

Heterochrony is defined as “a genetic shift in timing of the development of a tissue or anatomical part, or in the onset of a physiological process, relative to an ancestor”.[11] Heterochrony can lead to a modification in shape, size and/or behavior of an organism through a variety of different ways. With heterochrony being more of an umbrella term, there are two different types of heterochrony where development timing is altered: paedomorphosis and peramorphosis. These terms refer to deceleration and acceleration of development, respectively.[12] With neoteny (as described above) being defined as retention of juvenile features into adulthood, neoteny falls under paedomorphosis, as physical development of features is slowed.

Human evolution

Many prominent evolutionary theorists propose that neoteny has been a key feature in human evolution. Stephen Jay Gould believed that the "evolutionary story" of humans is one where we have been "retaining to adulthood the originally juvenile features of our ancestors".[13] J. B. S. Haldane mirrors Gould's hypothesis by stating a "major evolutionary trend in human beings" is "greater prolongation of childhood and retardation of maturity."[3] Delbert D. Thiessen said that "neoteny becomes more apparent as early primates evolved into later forms" and that primates have been "evolving toward flat face."[14] However, in light of some groups using arguments based around neoteny to support racism, Gould also argued "that the whole enterprise of ranking groups by degree of neoteny is fundamentally unjustified" (Gould, 1996, pg. 150).[15]

Doug Jones, a visiting scholar in anthropology at Cornell University, said that human evolution's trend toward neoteny may have been caused by sexual selection in human evolution for neotenous facial traits in women by men with the resulting neoteny in male faces being a "by-product" of sexual selection for neotenous female faces. Jones said that this type of sexual selection "likely" had a major role in human evolution once a larger proportion of women lived past the age of menopause. This increasing proportion of women who were too old to reproduce resulted in a greater variance in fecundity in the population of women, and it resulted in a greater sexual selection for indicators of youthful fecundity in women by men.[16]

The anthropologist Ashley Montagu said that the fetalized Homo erectus represented by the juvenile Mojokerto skull and the fetalized australopithecine represented by the juvenile Australopithecus africanus skull would have had skulls with a closer resemblance to those of modern humans than to those of the adult forms of their own species. Montagu further listed the roundness of the skull, thinness of the skull bones, lack of brow ridges, lack of sagittal crests, form of the teeth, relative size of the brain and form of the brain as ways in which the juvenile skulls of these human ancestors resemble the skulls of adult modern humans. Montagu said that the retention of these juvenile characteristics of the skull into adulthood by australopithecine or Homo Erectus could have been a way that a modern type of human could have evolved earlier than what actually happened in human evolution.[17]

The psychiatrist Stanley Greenspan and Stuart G. Shanker proposed a theory in The First Idea of psychological development in which neoteny is seen as crucial for the "development of species-typical capacities" that depend upon a long period of attachment to caregivers for the opportunities to engage in and develop their capacity for emotional communication. Because of the importance of facial expression in the process of interactive signaling, neotenous features, such as hair loss, allow for more efficient and rapid communication of socially important messages that are based on facially expressive emotional signaling.[18]

Other theorists have argued that neoteny has not been the main cause of human evolution, because humans only retain some juvenile traits, while relinquishing others.[19] For example, the high leg-to-body ratio (long legs) of adult humans as opposed to human infants shows that there is not a holistic trend in humans towards neoteny when compared to the other great apes.[19][20] Andrew Arthur Abbie agrees, citing the gerontomorphic fleshy human nose and long human legs as contradicting the neoteny hominid evolution hypothesis, although he does believe humans are generally neotenous.[7] Brian K. Hall also cites the long legs of humans as a peramorphic trait, which is in sharp contrast to neoteny.[21]

On the balance, an all or nothing approach could be regarded as pointless, with a combination of heterochronic processes being more likely and more reasonable (Vrba, 1996).

Cooked food and protective genome simplification

Based on calculations that show that more complex gene networks are more vulnerable to mutations as more conditions that are necessary but not sufficient increases the risk of one of them being hit, there is a theory that mutagens in food cooked by human ancestors short of modern human intelligence that was more likely to be burnt than in modern cooking selected against complex gene networks. This theory successfully predicts that the human genome is shorter than other Great Ape genomes and that there are significantly more defunct pseudogenes with functional homologs in the chimpanzee genome than vice versa. While the protein coding portion of the FOXP2 gene is identical to that in Neanderthals, there is one point mutation in the regulatory part thereof (modern humans having a T where Neanderthals and all nonhuman vertebrates have an A). The observation that the effect of that difference is that the modern human FOXP2 gene does not interact with RNA from other genes while all other vertebrate including Neanderthal varieties did agrees with the idea that modern human origins was marked by the elimination (not formation) of complex gene networks, as predicted by this model. The researchers behind the theory argue that neoteny is a side effect of the destruction of gene networks preventing the firing of genetic activity patterns that marked adulthood in prehuman ancestors.[22][23]

Growth pattern of children

In 1943 Konrad Lorenz noted that a newborn infant's rounded facial features might encourage guardians to show greater care for them, due to their perceived cuteness. He labeled this the kewpie doll effect, because of their similarity to the so-named doll.[24]

Desmond Collins who was an Extension Lecturer of Archaeology at London University[25] said that the lengthened youth period of humans is part of neoteny.

Physical anthropologist Barry Bogin said that the pattern of children's growth may intentionally increase the duration of their cuteness. Bogin said that the human brain reaches adult size when the body is only 40 percent complete, when "dental maturation is only 58 percent complete" and when "reproductive maturation is only 10 percent complete". Bogin said that this allometry of human growth allows children to have a "superficially infantile" appearance (large skull, small face, small body and sexual underdevelopment) longer than in other "mammalian species". Bogin said that this cute appearance causes a "nurturing" and "care-giving" response in "older individuals".[26]

Genetic diversity, relaxed sexual selection and immunity

While upper body strength is on average more sexually dimorphic in humans than in most other primates except gorillas, there is fossil evidence that male upper body strength and muscular sexual dimorphism in the upper body during human evolution peaked in Homo erectus and decreased along with overall robustness during the evolution of Homo sapiens with its neotenic traits. The fact that Homo sapiens survived while archaic human species that retained erectus-like sexual dimorphism in upper body strength died out contradicts the interpretation that enhanced chance of the species to survive makes taxa with high sexual dimorphism more species-rich on average, but can be explained by the theory that rampant sexual selection cause rapid speciation at the expense of genetic variation within species. This theory holds that strong sexual selection separate populations to little or no interbreeding so that new species are formed, but also homogenize each population/species by unforgiving sexual selection against differences from a "species norm" which makes the species more adapted to its specific environment but decreases the chance of some individuals of the species surviving environmental change. The predicted result is that while taxa with high sexual selection speciate fast, the resulting species are picked off one by one when the environment changes between different states until the taxon dies out, while species-poorer taxa with high intraspecies diversity and low sexual selection have species that survive over many climate changes. Neoteny in Homo sapiens is explained by this theory as a result of relaxed sexual selection shifting human evolution into a less speciation-prone but more intraspecies adaptable strategy, decreasing sexual dimorphism and making adults assume a more juvenile form. As a possible trigger of such a change, it have been cited that while the Neanderthal version of the FOXP2 gene that is located in the middle of the largest "neanderthal desert" region of the genome in which no modern humans have archaic human admixture differed on only one point from the modern human version (not two points as the difference between chimpanzees and modern humans) interacted strongly with other genes and was part of a gene regulatory network, the derived mutation that is unique to the modern human version of the gene knocked out the attachment to which RNA strains from other genes connected to it so that the gene was disconnected from its former genetic network. It is suggested that since the FOXP2 gene controls synapses, its disconnection from a formerly complex network of genes instantly removed many instincts including ones that drove sexual selection. It is also suggested that it allowed more genetic variants that affect the phenotype to accumulate in humans, which in combination with increased synaptic plasticity made modern humans more able to survive environmental change and to colonize new environments and innovate. The theory that the origin of complex language was the most recent step in human evolution is considered unlikely as storytelling about past environments would be of little use in droughts with novel distributions of water while individual ability to make correct predictions would be useful and allow for differential survival that could eliminate the archaic version altogether, as opposed to selection for language in which some primitives could use imitation as long as there were enough storytellers in the group to keep the knowledge alive for long times which predicts that some individuals would have retained the archaic version if the modern version was for language. Homo sapiens is known from fossils to have had a mix of modern neotenic traits and older non-neotenic traits from its origin some 300000 years ago to the transition to early agriculture when the non-neotenic traits disappeared, which is theorized to be due to selection for the immune system adapting to survive a higher pathogen load caused by agriculture and men who retained more childlike traits being less burdened by weakening of the immune system from upper body musculature competing with the immune system over nutrients. It is argued that the genetic evidence of only a small part of the male population of the time of early agriculture passing on their Y chromosomes can be explained by the heredity of non-neotenic traits causing the male descendants of the non-neotenic men who were not killed by diseases in one generation to die from them in subsequent generations, leaving no Y chromosome evidence of their short term continuation of paternal bloodlines in present humans. Sexual selection for stereotypic masculinity causing most men to fail to breed is ruled out as it would have selected against neoteny, not for as the archaeological evidence shows.[27][28]

Milder punishment as a survival advantage

One theory of the premise that Stone Age humans did not record birth date but instead assumed age based on appearance holds that if milder punishment to juvenile delinquents existed in Paleolithic times, it would have imparted milder punishment for longer on those retaining a more youthful appearance into adulthood. This theory holds that those who got milder punishment for the same breach of rules had the evolutionary advantage, passing their genes on while those who got more severe punishment had more limited reproductive success due to either limiting their survival by following all rules or by being severely punished.[29][30]

Neotenous features elicit help

The Multiple Fitness Model proposes that the qualities that make babies appear cute to adults additionally look "desirable" to adults when they see other adults. Neotenous features in adult females may help elicit more resource investment and nurturing from adult males. Likewise, neotenous features in adult males may similarly help elicit more resource investment and nurturing from adult females in addition to possibly making neotenous adult males appear less threatening and possibly making neotenous adult males more able to elicit resources from "other resource-rich people". Therefore, it could be adaptive for adult females to be attracted to adult males that have "some" neotenous traits.[31]

Neotenous features elicits fitness benefits for mimickers. From the point of view of the mimicker, the neoteny expression signals appeasement or submissiveness. Thus, extra parental or alloparental care will be most likely be administered because the mimicker appears to be more childlike and maybe ill equipped to survive on its own. On the other hand, the recipient often faces aggression because of this signaled vulnerability.[32]

Caroline F. Keating et al. tested the hypothesis that adult male and female faces with more neotenous features would elicit more help than adult male and female faces with less neotenous features. Keating et al. digitally modified photographs of faces of African-Americans and European Americans to make them appear more or less neotenous by either enlarging or decreasing the size of their eyes and lips. Keating et al. said that the more neotenous white male, white female and black female faces elicited more help from people in the United States and Kenya, but the difference in help from people in the United States and Kenya for more neotenous black male faces was not significantly different from less neotenous black male faces.[33]

A 1987 study using 20 Caucasian subjects found that "babyfaced" individuals are assumed by both Korean and U.S. participants to possess more childlike psychological attributes than their mature-faced counterparts.[32]

In her dissertation from the University of Michigan, Sookyung Cho explained how perception of cuteness can contribute to perception of value. Different physical cues were shown to trigger protective feelings from their adult caregivers or other adults from which they engaged in interaction.[34] Participants in the study were asked to design their own version of a cute rectangle. They were allowed to edit the rectangle in terms of shape roundedness, color, size, orientation, etc. Associational coefficients showed that shapes with a smaller area and rounder features were found to be cuter, and that lighter coloring and contrast playing a lesser but important role in predicting cuteness.[34]

As an additional part of the study the asymmetric dominance paradigm was introduced, where a decoy option is presented to observe how it affects a person’s decision on a certain matter. In the United States, this asymmetric dominance paradigm induced a person to be more prone to a cuter item and in Korea the opposite effect occurred. Cho concluded that this may be due to a different attitude toward cuteness, and so related to neoteny the advantages may be different in different countries.[34]

Brain

The developmental psychologist Helmuth Nyborg said that a testable hypothesis can be made using his General Trait Covariance-Androgen/Estrogen (GTC-A/E) model with regards to "neoteny". Nyborg said that the hypothesis is that "feminized", slower maturing, "neotenic" "androtypes" will differ from "masculinized", faster maturing "androtypes" by having bigger brains, more fragile skulls, bigger hips, narrower shoulders, less physical strength, live in cities (as opposed to living in the countryside) and by receiving higher performance scores on ability tests. Nyborg said that if the predictions made by this hypothesis are true, then the "material basis" of the differences would be "explained". Nyborg said that some ecological situations would favor the survival and reproduction of the "masculinized," faster maturing "androtypes" due to their "sheer brutal force" while other ecological situations would favor the survival and reproduction of the "feminized," slower maturing, "neotenic" "androtypes" due to their "subtle tactics."[35]

Aldo Poiani who is an evolutionary ecologist at Monash University, Australia,[36] said that he agrees that neoteny in humans may have become "accelerated" through "two-way sexual selection" whereby females have been choosing smart males as mates and males have been choosing smart females as mates.[37]

Somel et al. said that 48% of the genes that affect the development of the prefrontal cortex change with age differently between humans and chimpanzees. Somel et al. said that there is a "significant excess of genes" related to the development of the prefrontal cortex that show "neotenic expression in humans" relative to chimpanzees and rhesus macaques. Somel et al. said that this difference was in accordance with the neoteny hypothesis of human evolution.[38]

In terms of brain size differences, it has been noted that given the larger skull in neoteny humans, brain volume may be larger than an average human brain. It has been hypothesized that this is one mode of which the brains of Homo sapiens grew as a species, as the prolonged development of neurons may have led to hypermorphosis, or excessive neuronal growth. Especially in the prefrontal cortex, brain pruning from childhood may be slower than usual, allowing for more time for neuronal maturation. This prolongs the transformation of otherwise very juvenile features.

Bruce Charlton, a Newcastle University psychology professor, said what looks like immaturity — or in his terms, the "retention of youthful attitudes and behaviors into later adulthood" — is actually a valuable developmental characteristic, which he calls psychological neoteny.[39] In fact, the ability of an adult human to learn is considered a neotenous trait.[40]

However, some studies may suggest the opposite of this idea of neoteny being beneficial. In general, the process of learning and developing new skills can be attributed to plasticity of neurons in the brain, especially in the prefrontal cortex for higher order decisions and activity. As neurons go through ontogeny and maturity, it becomes more difficult to make new neuronal connections and change already present pathways and connections. However, during juvenile periods, cortical neurons are described to have higher plasticity and metabolic activity. In cases with neoteny, neurons are lingering in their more juvenile states since development is decelerated.[41] On the surface this seems beneficial for the increased potential of younger cells. However, this may not be the case, as the consequences of the increased cellular activity must be taken into account.[41]

In general, oxidative phosphorylation is the process used to supply energy for neuronal processes in the brain. When resources for oxidative phosphorylation are exhausted, neurons turn to aerobic glycolysis in the place of oxygen. However, this can be taxing on a cell. Given that the neurons in question retain juvenile characteristics, they may not be entirely myelinated. Bufill, Agusti, Blesa et. al note how “The increase of the aerobic metabolism in these neurons may lead, however, to higher levels of oxidative stress, therefore, favoring the development of neurodegenerative diseases which are exclusive, or almost exclusive, to humans, such as Alzheimer’s disease.”[41] Specifically through various studies of the brain, aerobic glycolysis activity has been detected at high levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which has functionality regarding the working memory.[41] Stress on these working memory cells may support conditions related to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease.

Physical attractiveness

Women

Montagu said that the following neotenous traits are in women when compared to men: more delicate skeleton, smoother ligament attachments, smaller mastoid processes, reduced brow ridges, more forward tilt of the head, narrower joints, less hairy, retention of fetal body hair, smaller body size, more backward tilt of pelvis, greater longevity, lower basal metabolism, faster heartbeat, greater extension of development periods, higher pitched voice and larger tear ducts.[3]

In a cross-cultural study, more neotenized female faces were the most attractive to men while less neotenized female faces were the least attractive to men, regardless of the females' actual age.[16] Using a panel of Asian, Hispanic and White judges, Michael R. Cunningham found that the Asian, Hispanic and white female faces found most attractive were those that had "neonate large eyes, greater distance between eyes, and small noses"[42] and his study led him to conclude that "large eyes" were the most "effective" of the "neonate cues".[42] Cunningham also said that "shiny" hair may be indicative of "neonate vitality".[42]

Cunningham said that there was a "difference" in the preferences of Asian and White judges. Cunningham said that Asian judges preferred women with "less mature faces" and smaller mouths than the White judges.[42] Cunningham hypothesized that this difference in preference may stem from "ethnocentrism" since "Asian faces possess those qualities", so Cunningham re-analyzed the data with "11 Asian targets excluded" and he concluded that "ethnocentrism was not a primary determinant of Asian preferences."[42] Using a panel of Blacks and Whites as judges, Cunningham said that more neotenous faces were perceived as having both higher "femininity" and "sociability".[42]

In contrast, Cunningham said that faces that were "low in neoteny" were judged as "intimidating".[42] Upon analyzing the results of his study Cunningham concluded that preference for "neonate features may display the least cross-cultural variability" in terms of "attractiveness ratings".[42] In a study of Italian women who have won beauty competitions, the study said that the women had faces characterized by more "babyness" traits compared to the "normal" women used as a reference.[43] In a study of sixty Caucasian female faces, the average facial composite of the fifteen faces considered most attractive differed from the facial composite of the whole by having a reduced lower facial region, a thinner jaw, and a higher forehead.[44]

In a solely Westernized study, it was recorded that the high ratio of neurocranial to lower facial features, signified by a small nose and ears, and full lips, is viewed interchangeably as both youthful and or neotenous.[16] This interchangeability between neotenous features and youth leads to the idea that male attraction to youth may also apply to females that display exaggerated age-related cues. For example, if a female was much older but retained these “youthful” features, males may find her more favorable over other females who look their biological age. Beyond the face value of what males find physically attractive, secondary sexual characteristics related to body shape are factored in so adults may be able to recognize other adults from juveniles. In fact, a major part of the cosmetic world is built around capitalizing on enhancing these features. Making eyes and lips appear larger as well as reducing the appearance of any age-related blemishes such as wrinkles or skin discoloration are some of the key target areas of this industry.[45]

Doug Jones, a visiting scholar in anthropology at Cornell University, said that there is cross-cultural evidence for preference for facial neoteny in women, because of sexual selection for the appearance of youthful fecundity in women by men. Jones said that men are more concerned about women's sexual attractiveness than women are concerned about men's sexual attractiveness. Jones said that this greater concern over female attractiveness is unusual among animals, because it is usually the females that are more concerned with the male's sexual attractiveness in other species. Jones said that this anomalous case in humans is due to women living past their reproductive years and due to women having their reproductive capacity diminish with age, resulting in the adaption in men to be selective against physical traits of age that indicate lessening female fecundity. Jones said that the neoteny in men's faces may be a "by-product" of men's attraction to indicators of "youthful fecundity" in "adult females". [16]

Likewise, neotenous features have also been loosely linked to providing information about levels of ovarian function, which is another integral part of sexual selection. Both of these factors, seeming like extra help is needed as well as neotenous features expression, being tied to optimal ovarian function, lead to a fitness advantage because males respond positively. However, it was noted that neotenous face structures are not the only thing to be taken into consideration when thinking about attractiveness and mate selection. Once again, secondary sex characteristics come into play because they are dominated by the endocrine system and appear only when sexual maturity is reached. The facial features are ever present and may not be the strongest case for sexual selection.[32]

Other scientists, noting that other primates have not evolved neoteny to the same extent as humans despite fertility being as reproductively significant for them, argue that if human children need more parental investment than nonhuman primate young, that would have selected for a preference for more experienced females more capable of providing parental care. As this would make experience more relevant for effective reproductive success (producing offspring that survive to reproductive age, as opposed to simply the number of births) and therefore more able to compensate for a slight to moderate decrease in biological fertility from recent sexual maturity to late pre-menopausal life, these scientists argue that the sexual selection model of neoteny makes the false prediction that primates that need less parental investment than humans should display more neoteny than humans.[46][47]

Men

A study was conducted on the attractiveness of males with the subject of the skull and its application in human morphology, using psychology and evolutionary biology to understand selection on facial features. It found that averageness was the result of stabilizing selection, whereas facial paedomorphosis or juvenile traits had been caused by directional selection.[48] In directional selection, a single phenotypic trait is driven by selection toward fixation in a population. In contrast, in stabilizing selection both alleles are driven toward fixation (or polymorphism) in a population.[49] To compare the effects of directional and stabilizing selection on facial paedomorphosis Wehr used graphic morphing to alter appearances to make faces appear more or less juvenile. The results concluded that the effect of averageness was preferred nearly twice over juvenile trait characteristics which indicates that stabilizing selection influences facial preference, and averageness was found more attractive than the retention of juvenile facial characteristics. It was perplexing to find that women tend to prefer the average facial features over the juvenile, because in animals the females tend to drive sexual selection by female choice and the Red Queen hypothesis.[48]

Because men generally exhibit uniform preference for neotenous women's faces, Elia (2013) questioned if women's varying preferences for neotenous men's faces could "help determine" the range of facial neoteny in humans.[50]

Neoteny and its connection with human specialization features

Neoteny is not a ubiquitous trait of the human phenotype. Human expression timing, compared to chimpanzee, has a completely different trajectory uncovering that there is no uniform shift in developmental timing. Humans undergo this neotenous shift once sexual maturity is reached. A question prompted by the Mehmet Somel et al. study, is whether or not human-specific neotonic changes are indicative of human- specific cognitive traits. The tracking of where developmental landmarks occur in humans and other primates is a step towards a better understanding of how neoteny manifests specifically in our species and how it may contribute to our specialized features, such as smaller jaws. In humans, the neotonic shift is concentrated around a group of gray matter genes. This shift in neotonic genes also coincides with cortical reorganization that is related to synaptic elimination and is at a much more rapid pace over others during adolescence. It is also linked to the development of linguistic skills and the development of certain neurological disorders like ADHD.[38]

Among primates and early humans

Delbert D. Thiessen said that Homo sapiens are more neotenized than Homo erectus, Homo erectus was more neotenized than Australopithecus, Great Apes are more neotenized than Old World monkeys and Old World monkeys are more neotenized than New World monkeys.[14]

Nancy Lynn Barrickman said that Brian T. Shea concluded by multivariate analysis that Bonobos are more neotenized than the common chimpanzee, taking into account such features as the proportionately long torso length of the Bonobo.[51] Montagu said that part of the differences seen in the morphology of "modernlike types of man" can be attributed to different rates of "neotenous mutations" in their early populations.[17]

Regarding behavioral neoteny, Mathieu Alemany Oliver says that neoteny partly (and theoretically) explains stimulus seeking, reality conflict, escapism, and control of aggression in consumer behavior.[52] However, if these characteristics are more or less visible among people, Alemany Oliver argues, it is more the fact of cultural variables than the result of different levels of neoteny. Such a view makes behavioral neoteny play a non-significant role in gender and race differences, and puts an emphasis on culture.

Specific neotenies

Populations with a history of dairy farming have evolved to be lactose tolerant in adulthood, whereas other populations generally lose the ability to break down lactose as they grow into adults.[53]

Down syndrome neotenizes the brain and body.[54] The syndrome is characterized by decelerated maturation (neoteny), incomplete morphogenesis (vestigia) and atavisms.[54]

See also

References

- Bednarik RG (2011). The Human Condition. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9353-3. ISBN 978-1-4419-9352-6. (page 134), cited by:

Achrati A (November 2014). "Neoteny, female hominin and cognitive evolution". Rock Art Research. 31 (1): 232–238.

"In humans, neoteny is manifested in the resemblance of many physiological features of a human to a late-stage foetal chimpanzee. These foetal characteristics include hair on the head, a globular skull, ear shape, vertical plane face, absence of penal bone (baculum) in foetal male chimpanzees, the vagina pointing forward in foetal ape, the presence of hymen in neonate ape, and the structure of the foot. 'These and many other features', Bednarik says, 'define the anatomical relationship between ape and man as the latter's neoteny'". - Gould SJ (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

- Montagu A (1989). Growing Young (2nd ed.). Granby, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89789-167-7. Retrieved 19 July 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu P (2007). Evolution. USA: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-60980-368-1.

- "Why Do Men Find Women With Larger Eyes Attractive?". Zidbits - Learn something new everyday!. 2 June 2011.

- Smith JM (1958). The Theory of Evolution. Cambridge University Press.

- Henke W, Tattersall W, eds. (2007). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. 1. NY: Springer Books. ISBN 978-3-540-33761-4.

- Hetherington R (2010). The Climate Connection: Climate Change and Modern Human Evolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14723-1.

- Thompson JL, Krovitz GE, Nelson AJ, eds. (December 2003). Patterns of Growth and Development in the Genus Homo. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-54256-5.

- Reed KE, Fleagle JG, Leakey RE, eds. (March 2013). The paleobiology of Australopithecus. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-5919-0.

- "the definition of heterochrony". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- McNamara KJ (2012-06-01). "Heterochrony: the Evolution of Development". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 5 (2): 203–218. doi:10.1007/s12052-012-0420-3. ISSN 1936-6434.

- Gould SJ (2008). "A biological homage to Mickey Mouse". Ecotone. 4 (1): 333–40. doi:10.1353/ect.2008.0045. S2CID 144159557.

- Thiessen DD (1997). Bittersweet destiny: the stormy evolution of human behavior. N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-245-1.

- Gould SJ (1996). The Mismeasure of Man. N.Y.: W.W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31425-0.

- Jones D, Brace CL, Jankowiak W, Laland KN, Musselman LE, Langlois JH, et al. (December 1995). "Sexual selection, physical attractiveness, and facial neoteny: cross-cultural evidence and implications [and comments and reply]". Current Anthropology. 36 (5): 723–48. doi:10.1086/204427.

- Montagu MA (1955). "Time, Morphology, and Neoteny in the Evolution of Man". American Anthropologist. 57 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1525/aa.1955.57.1.02a00030.

- Greenspan SI, Shanker SG (2004). The first idea: How symbols, language, and intelligence evolved from our primate ancestors to modern humans. Cambridge, MA, US: Da Capo Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-306-81449-5.

- Rantala MJ (September 2007). "Evolution of nakedness in Homo sapiens". Journal of Zoology. 273 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00295.x. S2CID 14182894.

- Shea BT (1989). "Heterochrony in human evolution: the case for neoteny reconsidered". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 80: 69–101. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330320505.

- Hall BK, Hallgrímsson B, Monroe WS (2008). Strickberger's evolution: the integration of genes, organisms and populations. Canada: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9.

- Provost JJ, Colabroy KL, Kelly BS, Wallert M (2016). The Science of Cooking: Understanding the Biology and Chemistry Behind Food and Cooking. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-67420-8.

- Richards JE, Hawley RS (2010). The human genome : a user's guide (3rd ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-333445-9.

- Lorentz (1943). "Die angeborenen Formen möglicher Erfahrung". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie (5): 234–409.

- "Special Issue: Early Man". World Archaeology Volume. 2 (1): 112. 1970. doi:10.1080/00438243.1970.9979467.

- Bogin B (1997). "Evolutionary Hypotheses for Human Childhood" (PDF). Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 40: 63–89. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8644(1997)25+<63::aid-ajpa3>3.0.co;2-8. hdl:2027.42/37682.

- Spier F (March 2015). Big history and the future of humanity. John Wiley & Sons.

- Austad SN, Finch CE (2017). "Human life history evolution: new perspectives on body and brain growth". On Human Nature. Elsevier. pp. 221–234. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420190-3.00014-4. ISBN 978-0-12-420190-3.

- Rolls ET (2013). Emotion and decision making explained. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965989-0.

- Dubreuil B (2010). Human Evolution and the Origins of Hierarchies: The State of Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67036-5.

- Simpson JA, Kenrick DT (1997). Evolutionary Social Psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-805-81905-2.

- McArthur LZ, Berry DS (June 1987). "Cross-Cultural Agreement in Perceptions of Babyfaced Adults" (PDF). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 18 (2): 165–192. doi:10.1177/0022002187018002003. S2CID 145782864.

- Keating CF, Randall DW, Kendrick T, Gutshall KA (2003). "Do Babyfaced Adults Receive More Help? The (Cross-Cultural) Case of the Lost Resume" (PDF). Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 27 (2): 89–109. doi:10.1023/A:1023962425692. S2CID 53979877.

- "Aesthetic and Value Judgment of Neotenous Objects: Cuteness as a Design Factor and its Effects on Product Evaluation". hdl:2027.42/94009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nyborg H (1994). Hormones, sex and society: The science of physicology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-275-94608-1.

- "Author: Aldo Poiani". Fifteen eighty four: Academic Perspectives from Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- Poiani A (2010). Animal Homosexuality: A biosocial perspective. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19675-8.

- Somel M, Franz H, Yan Z, Lorenc A, Guo S, Giger T, Kelso J, Nickel B, Dannemann M, Bahn S, Webster MJ, Weickert CS, Lachmann M, Pääbo S, Khaitovich P (April 2009). "Transcriptional neoteny in the human brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (14): 5743–8. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5743S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900544106. PMC 2659716. PMID 19307592.

- Risen C (10 December 2006). "Psychological Neoteny". The New York Times.

- Young JZ, Hobbs MJ (1975). The Life of Mammals (2nd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-857156-8.

- Bufill E, Agustí J, Blesa R (2011). "Human neoteny revisited: The case of synaptic plasticity". American Journal of Human Biology. 23 (6): 729–39. doi:10.1002/ajhb.21225. PMID 21957070. S2CID 30782772.

- Cunningham MR, Roberts AR, Barbee AP, Druen PB, Wu CH (1995). "Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours": consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 68 (2): 261–79. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.261. S2CID 27778786.

- Sforza C, Laino A, D'Alessio R, Grandi G, Binelli M, Ferrario VF (January 2009). "Soft-tissue facial characteristics of attractive Italian women as compared to normal women". The Angle Orthodontist. 79 (1): 17–23. doi:10.2319/122707-605.1. PMID 19123721.

- Perrett DI, May KA, Yoshikawa S (March 1994). "Facial shape and judgements of female attractiveness". Nature. 368 (6468): 239–42. Bibcode:1994Natur.368..239P. doi:10.1038/368239a0. PMID 8145822. S2CID 4371695.

- Furnham A, Reeves E (May 2006). "The relative influence of facial neoteny and waist-to-hip ratio on judgements of female attractiveness and fecundity". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 11 (2): 129–41. doi:10.1080/13548500500155982. PMID 17129903. S2CID 35459243.

- Ellison PT (September 2017). Reproductive Ecology and Human Evolution. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315128467. ISBN 9781315128467.

- Furuichi T, Yamagiwa J, Aureli F, eds. (June 2015). Dispersing primate females: Life history and social strategies in male-philopatric species. Primatology Monographs. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55480-6. ISBN 978-4-431-55479-0. S2CID 39655593.

- Wehr P, MacDonald K, Lindner R, Yeung G (December 2001). "Stabilizing and directional selection on facial paedomorphosis: Averageness or juvenilization?". Human Nature. 12 (4): 383–402. doi:10.1007/s12110-001-1004-z. PMID 26192413. S2CID 27737675.

- Bergstrom CT, Dugatkin LA (2012). Evolution. W. W. Norton. pp. 218, 221. ISBN 978-0-393-60104-6.

- Elia IA (2013). "A Foxy View of Human Beauty: Implications of the Farm Fox Experiment for Understanding the Origins of Structural and Experiential Aspects of Facial Attractiveness". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 88 (3): 163–183. doi:10.1086/671486. PMID 24053070.

- Barrickman NL. Evolutionary relationship between life history and brain growth in anthropoid primates (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Duke University.

- Alemany Oliver M (2016). "Consumer Neoteny: An Evolutionary Perspective on Childlike Behavior in Consumer Society". Evolutionary Psychology. 14 (3): 1–11. doi:10.1177/1474704916661825.

- Johnson S. "Religion, Science and other Neotenous Behaviour" (PDF).

- Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness EF (1990). "Reflections on the pathogenesis of Down syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 7 (S7 Supplement): 38–51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320370707. PMID 2149972.