Nisenan

The Nisenan are a group of Native Americans and an Indigenous people of California from the Yuba River and American River watersheds in Northern California[1] and the California Central Valley. For generations, the Nisenan were mislabeled as Maidu, along with three other Tribes. The four Tribes are not Maidu Sub-groups.[2] Nisenan is its own separate and unique culture, customs, leaders, holy people and language. The Nisenan language has 13 dialects.

Because of these geographical barriers there are many customs and cultural practices that are unique to each region. Although they have existed in these regions prior to outside presence they are not recognized by the US government. The Nisenan previously had federal recognition via the Nevada City Rancheria. Some Nisenan people today are enrolled in the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, a federally recognized tribe.[3]

Name

The name Nisenan, derives from the ablative plural pronoun nisena·n, "from among us".[4]

The Nisenan have been called the Southern Maidu and Valley Maidu. While the term Maidu is still used widely, Maidu is an over-simplification of a very complex division of smaller groups or bands of Native Americans .

Territory

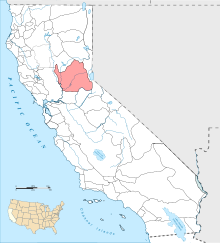

The Nisenan lived in Northern California, between the Sacramento River to the west and the Sierra Mountains to the east. The southern reach went to about Cosumnes River but north of Elk Grove and the Meadowview and Pocket regions of Sacramento, and the northern reach somewhere between the northern fork of the Yuba River and the southern fork of the Feather River.

Neighboring tribes included the Valley and North Sierra Miwok to the south, the Washoe to the east, the Konkow and Maidu to the north, and the Patwin to the west.

History

.jpg.webp)

Gold Rush

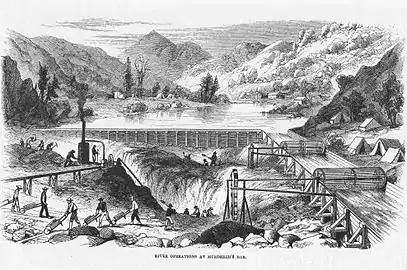

The Nisenan were initially unaffected by European-American influence and their initial meeting with the Spanish and U.S. expeditions were peaceful in the early nineteenth century. In 1833, a severe malaria epidemic hit which killed many of the Nisenan as well as other neighboring tribes. The 1849 Gold Rush led to the appropriation of their land, decimation of their resources, more disease, violence, and mass murder.[5] The influx of migrants created by the Gold Rush and their excessive use of the land caused a strain on the environment; this prompted a drought and starvation took over.[6] The Nisenan population dropped from approximately 9,000 to 2,500 people by 1995 and a fraction of the surviving Nisenan were left in the Sierra Nevada foothills and acquired low-wage jobs.[5]

Customs

Birth customs

Documented history about customs can be contradictory and not always reliable, as early anthropologists were often researching several regions at once, often well after disruptions and trauma to tribes had already occurred due to European contact.[7] According to some sources, if twins were born, they were often killed, along with the mother.[5] However according to Richard B. Johnson, current Tribal Chairman for the Nevada City Nisenan; "Our elders have said that twins were not killed, but were considered fortunate if both survived during infancy. Our tribe has ancestors who are twins."[8] Due to the frequency of stillborn births, cradleboards were always made after the birth of the child.[9] An expecting mother getting close to birth, avoided cold air, salt, meat, and cold water. After a birth, the new mother and her child would remain in the birthing hut for the first 16 days, with the husband maintaining a fire day and night.[10] The new mother slept in a seated position for the first sixteen days after birth,[11] with a heated flat stone placed on the belly to assist with the afterbirth.[12] A feast was essential after the sixteen days; during which the child would be celebrated with relatives and a name chosen.[9] Naming the child after an elder or ancestor was common. If there were no more names left to choose in a particular lineage, a close friend might allow the use of his family lineage to the parents.[9]

The umbilical cord was cut, with an obsidian knife, and the end of the cord was smeared with charcoal.[13] The mother started breastfeeding her child two days after his or her birth and children were usually weaned at two or three years old.[9]

Marriage customs

Marriage arrangements are now set by the couple themselves, but the parents chose the arrangements in older customs. Once both of their parents reached an agreement on the pairing, the couple was then officially engaged. Shells and beads were gifted between the two families, and an event was arranged to celebrate their communion. Before the union was consummated, the couple was educated on their specific marital responsibilities. The man proved his ability to care for his wife by providing gifts to his in-laws. Couples moved from the woman's home to their own place near the man's family.[5] During the process of the consummation of the marriage, the pair slept at a distance from each other for a number of nights. Each night, the man was allowed to advance closer towards the woman. The consummation was complete once they were "within touching distance."[14]

Mainly widows, widowers, and divorcees remarried without the engagement period as they no longer required guidance from elders. Female widows were allowed to remarry after a mourning period of six months to three years; men were allowed to remarry sooner than the women. Many women most often opted to return to their own people than to remarry. Marriage to husband's brother was also an option. Before any decisions to remarry, permission from deceased spouse's relatives was necessary as a form of respect.[15]

Death customs

Funeral burning rituals are one of the most prominent death ceremonies in the Nisenan community. It not only included the cremation of the body, but also of all of the deceased person's possessions.[16] Cremation was the most feasible practice for tribes, primarily for those of a nomadic lifestyle, due to easier transportation and to limit grave robberies.[17] The dead were reported to mingle in the surrounding space, before going to a land of the dead, an area that did not discriminate between good or bad.[16] The deceased have the ability to take the forms of either creatures or weather patterns, but were not welcomed by the living community. There is thought to be a distinguishable boundary between the living and dead, and even the mere mention of a deceased person's name was greatly frowned upon.[16]

Language

The Nisenan language encompasses 13 dialects that are as extensive as the language, itself. The language is spoken in the Sierra Nevada, between the Cosumnes River and Yuba River, as well as in the Sacramento Valley between the American River and Feather River.[18]

The were as many as 13 specific Nisenan dialects[19] but 8 that are documented.

Previously documented as only 4 dialects. These were:

- Valley Nisenan

- Northern Hill Nisenan

- Central Hill Nisenan

- Southern Hill Nisenan

Spanish influence

Spanish originally invaded and occupied California in the late 18th century. Franciscans missions were built in California to settle the area, spread the religion, extract resources from the land and enslave indigenous people. The Nisenan people had less interaction with Spanish settlers from the coast compared to neighboring tribes. They were relatively undisturbed by Spanish missionaries and religious missions, though Spanish and Mexican troops occasionally set foot on Nisenan land to capture enslaved indigenous people who had fled, many of whom in one particular example were of the neighboring Miwok tribe, find livestock, or traverse the land.[20]

Social organization

Nisenan, as with many of the tribes of central California, is not a strict political distinction, but are a group that shared a common language, with a wide spectrum on similar dialects. The Nisenan people historically have not been a unified polity but instead a number of small, self-sufficient, autonomous communities. Each community spoke a different variation of the Nisenan language, which has led to some inconsistency among the linguistic data on the language. The Nisenan tribes encompassed the traits of a Patriarchal society. The tribes adhered to a Patrilocal residence system and most likely followed a system of Patrilineal chief succession.[21] Because of the organization of descent, property customs also followed a Patriarchal means.[21]

Daily life

Housing

The Nisenan made two distinct living structure known as Hu, and K’um. Hu was the common structure in which villagers lived. These dome-shaped homes were typically built of a combination of tule, earth and wooden poles. Their floors were strewn with foliage and a fire occupied a clear space in the center of a floor. The smoke floated out through a corresponding hole in center of the roof. Earth was also piled on the outside of the Hu for additional insulation.[22] K’um was a partially subterranean dwelling where ceremonial practice and dances would take place.[23] These structures were more prominent in larger villages. The K’um would also be used to provide lodging for visitors. The floor of the K’um was partially dug in below ground level. The door was oriented to the east and opposite the door were drums. The K’um would have 2 to 4 major posts depending on its size for support. Placement of the post was important in that putting one in front of where the drums would go was considered bad luck.[22]

Food

An abundant source of food came from acorns. In the fall villagers would help forage for acorns. Long poles were used to acquire the acorns. Acorns were harvested in a granary. Acorns were then taken to be made into mush, gruels, or cakes. Pine nuts, berries, and other sorts of vegetations were harvested as well. Tule would be consumed by boiling it or roasting it over an open fire.[24] Men would typically be the ones that would hunt for game. In small parties they would hunt deer, elk and rabbits. Bears were hunted during the winter months when they were hibernating. Fishing was also popular in regions close to rivers. Freshwater fish like salmon, sturgeon, and trout were amongst the most popular. Food was not only limited to vegetation and game, but also insects. Grubs, earthworms, and yellow jackets were eaten. They would be smoked out with fire and collected.[22]

Currency and trade

Shell beads were used as a display of wealth and a form of currency. The beads were not shaved down by the Nisenan but were imported from coastal communities. Once worn down the shell beads would be punctured so they could be strung on strings. This currency was not always used with outside tribes.[22] The Valley Nisenan and Hill Nisenan frequently traded with each other. The Nisenan who lived in the valley traded fish, roots, shells, beads, salt, and feathers to the Hill Nisenan. they in turn would trade black acorns, pine nuts, berries, animal skins, and wood needed to make bows[23]

Current events

147 Nisenan currently reside in Nevada City, California. The tribe is not recognized by the government which prevents them from receiving federal protection and financial aid. Congress enacted the Rancheria Act of 1958 in an effort to disband the Rancheria System in California. Although 27 out of 38 Rancherias as well as additional tribes have been restored throughout the past 25 years, the Nisenan were the first to be denied restoration of their Rancheria in 2015. This withheld them from federal health and housing services, education programs, and job assistance programs. Today, 87 percent of the tribe live along or below California's poverty line. Extremely high rates of under-education, under-employment, drug and alcohol addiction, domestic violence, suicide, and poor health persist within the community. The main goal of the Nisenan people is to restore their identity and re-establish representation of their tribe. Nisenan Heritage Day is held annually to showcase ceremonial dances and allow attendees insight as well as participation in traditional practices such as basket weaving. Additional efforts are put towards educating people on their language as they view it as their "connection to the land itself."[25]

Notes

- Sturtevant, general editor; Handbook of North American Indians, Nisenan chapter; Wilson, Norman L. and Thowne, Arlean H., page 387 (Smithsonian Institution, 1987)

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY OF US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria. Comstock Bonanza Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0933994652.

- "Our Heritage." Archived 2014-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians. 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- Mithun, Marianne (2001). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-521-29875-9.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopeida: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 132.

- "The Gold Rush Impact on Native Tribes". PBS. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY of US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria (1 ed.). Nevada City, CA: Comstock Bonanza Press. pp. ix. ISBN 0933994656.

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY of US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria. Comstock Bonanza Press. p. x. ISBN 0933994656.

- Faye, Paul Louis (1923). Notes on the Southern Maidu. Vol. 20. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology: University of California Press. p. 35.

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY of US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria. Comstock Bonanza Press. p. 42. ISBN 0933994656.

- Beals, Ralph L. (1933). Ethnology of the Nisenan. Berkeley, California: University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. pp. 368–369.

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY of US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria (1 ed.). Nevada City, CA: Comstock Bonanza Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0933994656.

- Johnson, Richard (2018). HISTORY OF US: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria (1 ed.). Nevada City, CA: Comstock Bonanza Press. p. 42. ISBN 0933994656.

- Nelson, Kjerstie (1975). Marriage and Divorce Practices in Native California. Berkeley: University of California: Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology. pp. 12–13.

- Beals, Ralph L. (1933). Ethnology of the Nisenan. Berkeley, California: University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. pp. 371–372.

- Simmons, William S. (1997). "Indian Peoples of California". California History. 76 (2/3): 48–77. doi:10.2307/25161662. JSTOR 25161662.

- Splitter, Henry Winfred (1948). "Ceremonial and Legend of Central California Indians". Western Folklore. 7 (3): 266–271. doi:10.2307/1497550. JSTOR 1497550.

- Eatough, Andrew (1999-10-05). Central Hill Nisenan Texts with Grammatical Sketch. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520098060.

- NISENAN - Survey of California and Other Indian Languages, Department of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley

- Hurtado, Albert L. (2006). John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806137728.

Nisenan.

- Goldschmidt, Walter (1948). "Social Organization in Native California and the Origin of Clans". American Anthropologist. 50 (3): 444–456. doi:10.1525/aa.1948.50.3.02a00040. JSTOR 664293.

- Beals, Ralph Leon (1933). Ethnology of the Nisenan. University of California Press. p. 356.

- "Nisenan".

- Kroeber, A.L. (1929). The Valley Nisenan. University of California Press. p. 261.

- "The California Tribe the Government Tried to Erase in the 60s". Vice. 2018-01-17. Retrieved 2018-04-14.