Nutcracker syndrome

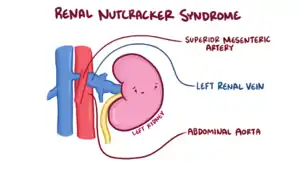

The nutcracker syndrome (NCS) results most commonly from the compression of the left renal vein (LRV) between the abdominal aorta (AA) and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), although other variants exist.[1][2] The name derives from the fact that, in the sagittal plane and/or transverse plane, the SMA and AA (with some imagination) appear to be a nutcracker crushing a nut (the renal vein). Furthermore, the venous return from the left gonadal vein returning to the left renal vein is blocked, thus causing testicular pain (colloquially referred to as "nut pain"). There is a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and diagnostic criteria are not well defined, which frequently results in delayed or incorrect diagnosis.[1] This condition is not to be confused with superior mesenteric artery syndrome, which is the compression of the third portion of the duodenum by the SMA and the AA.

| Nutcracker syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Nutcracker phenomenon, renal vein entrapment syndrome, mesoaortic compression of the left renal vein |

| |

| The nutcracker syndrome results from compression of the left renal vein between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. | |

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of NCS are all derived from the outflow obstruction of the left renal vein. The compression causes renal vein hypertension, leading to hematuria (which can lead to anemia)[3] and abdominal pain (classically left flank or pelvic pain).[4] The abdominal pain may improve or worsen depending on positioning.[4] Patients may also have orthostatic proteinuria, or the presence of protein in their urine depending on how they sit or stand.[5]

Since the left gonadal vein drains via the left renal vein, it can also result in left testicular pain[6] in men or left lower quadrant pain in women, especially during intercourse and during menstruation.[7] Occasionally, the gonadal vein swelling may lead to ovarian vein syndrome in women. Nausea and vomiting can result due to compression of the splanchnic veins.[6] An unusual manifestation of NCS includes varicocele formation and varicose veins in the lower limbs.[8] Another clinical study has shown that nutcracker syndrome is a frequent finding in varicocele-affected patients and possibly, nutcracker syndrome should be routinely excluded as a possible cause of varicocele and pelvic congestion.[9] In women, the hypertension in the left gonadal vein can also cause increased pain during menses.[9]

Etiology

In normal anatomy, the LRV travels between the SMA and the AA.[7] Occasionally, the LRV travels behind the AA and in front of the spinal column. NCS is divided based on how the LRV travels, with anterior NCS being entrapment by the SMA and AA and posterior NCS being compression by the AA and spinal column.[7] NCS can also be due to other causes such as compression by pancreatic cancer, retroperitoneal tumors, and abdominal aortic aneurysms.[7] Although other subtypes exist, these causes are more uncommon in comparison to entrapment by the SMA and the AA.[7] Patients with NCS have a tendency to have a tall and lean stature, as this can lead to a narrower gap between the SMA and the AA for the LRV. [10]

Diagnosis

Nutcracker syndrome is diagnosed through imaging such as doppler ultrasound (DUS), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and venography.[11] The selection of the imaging modality is a step-wise process. DUS is the initial choice after clinical suspicion based on symptoms. CT and MRI are used to follow up afterwards, and if further conrfirmation is necessary, venography is used to confirm.[11]

Doppler Ultrasound

Although its ability to detect renal vein compression is dependent on how a patient is positioned during imaging, DUS is recommended as an initial screening tool as it has a high sensitivity (69–90%) and specificity (89–100%). DUS measures the anteroposterior diameter, and a peak systolic velocity at least four times as fast as an uncompressed vein is indicative of NCS.[5]

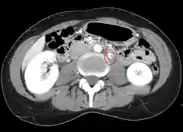

CT and MRI

CT and MRI can be used afterward to confirm compression by the AA and SMA with comprehensive measurements of the abdominal vasculature. A "beak sign" can often be seen in CT scans due to the LRV compression. However, CT and MRI cannot demonstrate the flow within the compressed vein. These two modalities can be used to confirm other evidence for NCS such as back-up of blood flow into the ovarian veins.[10][5]

Venography

If further confirmation is necessary, venography is used as the gold standard test in diagnosing nutcracker syndrome. A renocaval pullback mean gradient of >3 mmHg is considered diagnostic. Although this method continues to be the gold standard, values in unaffected individuals may be vary considerably, leading to some measurements in NCS patients to be similar to those in normal individuals.[11] This may be partly due to compensatory mechanisms in the vasculature as a result of the increased blood pressure. The invasive nature of the procedure is another consideration in comparison to DUS and CT/MRI as imaging modalities.[7]

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Treatment depends on the severity and symptoms. In addition to conservative measures, more invasive therapies include endovascular stenting,[4] renal vein re-implantation,[13] and gonadal vein embolization. The decision between conservative and surgical management is dependent on the severity of the symptoms.[11] Conservative management is used if the patient is a child and the hematuria is mild.[10] In contrast, more severe symptoms such as reduced renal function, flank pain, and anemia are managed with surgical interventions.[10]

Conservative management

Conservative management is advised in children as further growth may lead to an increase in tissue at the fork between the SMA and AA, providing room for the LRV to pass blood without obstruction.[11] Treatment in this case involves weight gain to build more adipose tissue, decreasing the compression. Venous blood may also be directed towards veins formed as a result of the higher blood pressure, which may contribute to symptomatic relief for individuals as they age.[11] 75% of adolescent patients have been found to have their symptoms resolved after two years. Medications that decrease blood pressure such as ACE inhibitors can also be used to reduce the proteinuria.[11]

Open and laparoscopic procedures

There are several different procedures available to manage NCS include:

- LRV transposition: The LRV is moved higher in the abdomen and re-implanted to the inferior vena cava (IVC) so that it is no longer being compressed.[5]

- Gonadal vein transposition: The gonadal veins are connected to the (IVC) to reduce the amount of blood backed up in the pelvis.[5]

- Renocaval bypass with saphenous vein: a segment of the great saphenous vein is used as a second connection between the LRV and the IVC to alleviate pressure build up.[5]

- Renal autotransplantation: transfer of a kidney from its original location into the body to another location to prevent venous compression.[5]

LRV transposition is the most common procedure done followed by renal autotransplantation and LRV bypass. [5]In all cases for open procedures, data is limited for long term follow-up. With respect to LRV transposition, most patients stated improvement of symptoms 70 months following the procedure.[5]

Laparoscopic procedures involve laparoscopic spleno-renal venous bypass and laparoscopic LRV-IVC transposition.[11] They are uncommon in comparison to open procedures, but the outcomes of such procedures are similar to those of open procedures.[11] Although robotic surgery is possible, data on robotic procedures is limited concerning outcomes and cost-effectiveness.[11]

Endovascular procedures

Endovascular interventions involve the use of stents to improve blood flow in the area of LRV impingement.[11] Following catheterization, venography is done to visualize the vasculature and can provide confirmatory diagnosis of NCS prior to stenting.[11] Following stenting, 97% of patients have had improvement of symptoms by sixth months following the procedure, and long term follow-up showed no recurrence of symptoms after 66 months. Although less invasive, risks involved include incorrect placement of the stent as well as stent dislodging and migration to the right atrium.[11] Furthermore, patients must be on anticoagulation therapy after stenting for three months.[11]

Gallery

Compression of the left renal vein (marked by the arrow) between the superior mesenteric artery (above) and the aorta (below) due to nutcracker syndrome.

Compression of the left renal vein (marked by the arrow) between the superior mesenteric artery (above) and the aorta (below) due to nutcracker syndrome. Thrombosis in the left renal vein associated with dilation.

Thrombosis in the left renal vein associated with dilation. A nutcracker. The legs of this nutcracker, with some imagination, could represent the superior mesenteric artery and abdominal aorta in nutcracker syndrome.

A nutcracker. The legs of this nutcracker, with some imagination, could represent the superior mesenteric artery and abdominal aorta in nutcracker syndrome.

References

- Kurklinsky AK, Rooke TW (June 2010). "Nutcracker phenomenon and nutcracker syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 85 (6): 552–9. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0586. PMC 2878259. PMID 20511485.

- Sugimoto I, Takashi O, Ishibashi H, Takeuchi N, Nagata Y, Honda Y (2001). "Left Renal Vein Entrapment Syndrome (Nutcracker Syndrome) treated with Left Renal Vein Transposition". JNP J Vasc Surg. 10: 503–7.

- Oteki T, Nagase S, Hirayama A, Sugimoto H, Hirayama K, Hattori K, Koyama A (July 2004). "Nutcracker syndrome associated with severe anemia and mild proteinuria". Clinical Nephrology. 62 (1): 62–5. doi:10.5414/CNP62062. PMID 15267016.

- Barnes RW, Fleisher HL, Redman JF, Smith JW, Harshfield DL, Ferris EJ (October 1988). "Mesoaortic compression of the left renal vein (the so-called nutcracker syndrome): repair by a new stenting procedure". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 8 (4): 415–21. doi:10.1067/mva.1988.avs0080415. PMID 3172376.

- White JM, Comerota AJ (April 2017). "Venous Compression Syndromes". Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 51 (3): 155–168. doi:10.1177/1538574417697208. PMID 28330436. S2CID 35732843.

- Hilgard P, Oberholzer K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Hohenfellner R, Gerken G (July 1998). "[The "nutcracker syndrome" of the renal vein (superior mesenteric artery syndrome) as the cause of gastrointestinal complaints]". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 123 (31–32): 936–40. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1024101. PMID 9721569.

- Gulleroglu K, Gulleroglu B, Baskin E (November 2014). "Nutcracker syndrome". World Journal of Nephrology. 3 (4): 277–81. doi:10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.277. PMC 4220361. PMID 25374822.

- Little AF, Lavoipierre AM (June 2002). "Unusual clinical manifestations of the Nutcracker Syndrome". Australasian Radiology. 46 (2): 197–200. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1673.2001.01037.x. PMID 12060163.

- Mohammadi A, Mohamadi A, Ghasemi-Rad M, Mladkova N, Masudi S (August 2010). "Varicocele and nutcracker syndrome: sonographic findings". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 29 (8): 1153–60. doi:10.7863/jum.2010.29.8.1153. PMID 20660448.

- Orczyk K, Wysiadecki G, Majos A, Stefańczyk L, Topol M, Polguj M (2017). "What Each Clinical Anatomist Has to Know about Left Renal Vein Entrapment Syndrome (Nutcracker Syndrome): A Review of the Most Important Findings". BioMed Research International. 2017: 1746570. doi:10.1155/2017/1746570. PMC 5742442. PMID 29376066.

- Ananthan K, Onida S, Davies AH (June 2017). "Nutcracker Syndrome: An Update on Current Diagnostic Criteria and Management Guidelines". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 53 (6): 886–894. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.02.015. PMID 28356209.

- Ahmed K, Sampath R, Khan MS (April 2006). "Current trends in the diagnosis and management of renal nutcracker syndrome: a review". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 31 (4): 410–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.05.045. PMID 16431142.

- Rudloff U, Holmes RJ, Prem JT, Faust GR, Moldwin R, Siegel D (January 2006). "Mesoaortic compression of the left renal vein (nutcracker syndrome): case reports and review of the literature". Annals of Vascular Surgery. 20 (1): 120–9. doi:10.1007/s10016-005-5016-8. PMID 16374539. S2CID 45878200.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Kimura K, Araki T (July 1996). "Images in clinical medicine. Nutcracker phenomenon". The New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (3): 171. doi:10.1056/NEJM199607183350305. PMID 8657215.