Old 666

Old 666 (B-17E 41-2666) was a World War II B-17 Flying Fortress bomber which was assigned to the United States' 19th and 43rd Bomb Groups in 1942–43. It is notable for being the aircraft piloted by Lt. Col. (then Captain) Jay Zeamer on the 16 June 1943 mission that would earn him and 2d Lt. Joseph Sarnoski each a Medal of Honor, and all other members of the crew the Distinguished Service Cross.

| Old 666 | |

|---|---|

| |

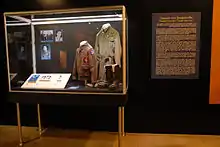

| Only known image of Old 666. | |

| Other name(s) | Lucy |

| Type | Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| Construction number | 2487 |

| Manufactured | March 1942 |

| Serial | 41-2666 |

| In service | 1942–1943 |

| Fate | Scrapped, September 1945 |

History

B-17E #41-2666 was built in Seattle, Washington in March 1942. It arrived in Hawaii in May 1942 for delivery to Australia. That same month, it was assigned to the 19th Bombardment Group.[1] Sometime after it arrived in Australia, 41-2666 was equipped with a trimetrogon camera array used in high-altitude topographical mapping.[2]

During the summer and fall of 1942, the aircraft was flown primarily by the 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron (PRS), usually while attached to the 19th.[3] Late in the year it was transferred to the 43rd Bomb Group, where on a mission in December 1942 it was damaged severely enough to be grounded for a period of time.[2] Nothing more is currently known about the aircraft until the following April, when it was again being flown by the 8th PRS. In May 1943, having gained a reputation as a “Hard Luck Hattie” for its record of damage and odd accidents, 41-2666 was transferred to the 65th Bomb Squadron, 43rd Bomb Group, at Seven-Mile Airstrip, located at Port Moresby, New Guinea.[4]

It was in the 65th that then-Captain Jay Zeamer, serving as squadron executive officer, requisitioned the aircraft for his crew, known as the “Eager Beavers,” to customize for their use in photo-mapping and reconnaissance work.[5] Besides significantly reducing the overall weight and replacing the engines, the crew installed additional .50 caliber machine guns, including a .50 mounted to the bombardier's deck in the nose that Zeamer could fire himself.[6] While that and the sheer number of guns on '666 was remarkable—the common gun complement on a Pacific B-17E was thirteen—what made Zeamer's upgrade unique in the Pacific was the crew's installation of twin .50s in both waist positions.[2]

As for a name, the regular crew referred to 41-2666 only as "666" or "the plane". The plane was indeed officially nicknamed "Lucy", but only shortly before the 16 June 1943 mission—not in time for the crew to begin referring to it as such.[5] Because of its specialized use for camera work, and despite their extensive work on the plane, Zeamer and his crew flew 41-2666 only five times, two of which were test hops. Bombing missions were flown in B-17s suited to that purpose, with their use of 41-2666 restricted to three photo-mapping missions.[7]

Mapping mission

The last of these missions occurred on June 16, 1943. It called for a solo B-17 to map the west coast of Bougainville, almost six hundred miles over mostly open ocean from Seven-Mile, in support of a planned invasion of the island later that year. Such mapping demanded rigorously straight and level flight for the duration to avoid blurring of the photos, and this mission would require a 22-minute such run over hostile territory.

Zeamer had volunteered for the mission when it was first requested in April, but weather and other factors forced postponements until the June date.[8][5] Twice before taking off at 4:00 a.m., June 16, Zeamer rejected orders to add to the mission a reconnaissance of Buka airdrome, located off Bougainville's northern tip. The mapping would be hazardous enough, he felt, without adding extended contact with the enemy just prior.[8]

Early arrival to the initial mapping point meant a half-hour delay in starting the mapping run; the sun was not high enough for the light necessary for topographic relief.[9] The delay prompted Zeamer to ask the crew's opinion on the Buka recon. All supported going ahead with it, considering their proximity. As a result, Zeamer adjusted course northeast to take them over Buka airstrip before heading into the mapping run down Bougainville's west coast.

Contemporary accounts from the crew report counting around fifty aircraft on either side of the Buka airstrip, with seventeen or eighteen Japanese aircraft either taxiing or taking off from Buka airstrip as "Old 666" covered the island. These were Japanese Navy fighters, Model 22 Zeroes of Air Squadron 251, most of which were usually based at Rabaul, New Britain, but had moved to Buka the previous day for their planned June 16 attack on Guadalcanal.[5] Zeamer began the mapping run, hoping that it could be finished before the enemy aircraft could reach their mapping altitude of 25,000 feet. Shortly before its completion, ineffectual passes from below were followed by a handful of Zeros enclosing the B-17 in a coordinated attack from below, two approaching from the rear and three fanned across the front. The combination left Zeamer unable to execute his usual defensive tactic of turning inside the line of fire of enemy aircraft attacking from the front; such a maneuver in this case would expose the B-17's belly to the other Zeros attacking from the front. Aware of their position now over Empress Augusta Bay, the primary mapping objective, Zeamer held course, hoping to fight it out.[10]

This first attack proved fatal for bombardier Sarnoski, who was mortally wounded by a 20mm shell which also badly injured the navigator, 1st Lt. Ruby Johnston. Another 20mm struck the side of the cockpit behind the pilots, sending shrapnel into the legs of Sgt. Johnny Able, the assistant flight engineer substituting as top turret gunner that day. It also struck the oxygen and hydraulic lines behind the cockpit, starting a fire. A third 20mm entered through the Plexiglass nose, destroying Zeamer's rudder pedals and instrument panel and delivering grievous wounds to Zeamer's left leg and slicing his right wrist. Farther back, radio operator Sgt. William Vaughan was grazed badly in the neck by a bullet. Back in the nose, despite being blown to the floor with a horrible gash in his side and another in his neck, Sarnoski regained his gun in time to counter a twin-engine fighter—variously described by crew members as either a Mitsubishi Ki-46 "Dinah" or Kawasaki Ki-45 "Nick"—pressing a new attack on the nose. Sarnoski drove the attacker off before it could inflict any more damage and then collapsed from his wounds.[11][5]

Having finished the mapping run and now needing oxygen, Zeamer dove the plane from 25,000 feet to around 10,000 feet, estimating his altitude from a change in manifold pressure, since the altimeter had been destroyed. After the dive, both Johnston and Able extinguished the oxygen fire using only their hands and rags.[12]

Leveling out, Zeamer continued to pilot "Old 666" despite excruciating pain and continued blood loss. Correctly assuming its forward guns were now inoperable, the Japanese began lining up on both sides of the B-17 to circle around, one by one in turn, to strafe the aircraft from the front. Zeamer was now able to apply the technique he'd been unable to use against the coordinated first pass: banking hard inside the firing angle of each approaching Zero, Zeamer both avoided the enemy's fire and allowed his rear gunners unfettered access to the Zeros as they passed by the B-17. This continued until finally, low on ammunition and fuel, around forty minutes after the initial attack, the last of the remaining Zeros returned home. While the crew reported downing five fighters, Japanese records show none were actually shot down, with one ditching early in the engagement due to engine failure and only three being damaged by return fire.[13]

Once out of danger, Sgt. Able piloted "Old 666" on a dead reckoning return heading determined by Zeamer while the unscathed substitute copilot, Lt. J.T. Britton, took stock of the damage to the crew and plane. Zeamer, drifting in and out of unconsciousness, advised Able on keeping course and level. Radio operator Vaughan, while nursing his neck wound, calculated a heading for Dobodura, an Allied airstrip on the eastern coast of Papua New Guinea, for an emergency landing. It was not expected that Zeamer would survive a return flight over the Owen-Stanley mountains to Port Moresby. Britton, having returned to his seat for the balance of the flight, landed at Dobodura without flaps or brakes, requiring him to ground loop the bomber near the end of the six-thousand-foot runway.[5]

In all, four members of the crew were wounded and one killed. The aircraft suffered damage to the instrument panel from being struck by a 20mm gun, and the pilot's rudder pedals were destroyed. For the completion of their mission despite the certainty of attack and their respective sacrifices, Sarnoski and Zeamer each received the Medal of Honor, with the remainder of the crew receiving the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor in esteem. The mission remains the most highly decorated in American history, and the Eager Beavers, individual decorations all considered, remain the most highly decorated air crew in U.S. history.[14] This mission was featured on the History Channel show Dogfights in an episode titled "Long Odds".[15]

After the mission

Seven of the eight Zero pilots who intercepted "Old 666" later participated in a strike on Allied shipping at Lunga Point that same day.[16] Two of them, Warrant Officer Yoshio Oki and Flight Petty Officer 2nd Class Suehiro Yamamoto, failed to return.[16][17]

By mid-1943, like most heavy bomb groups in the Pacific, the 43rd had mostly converted to the B-24.[18] The aging and much-abused Pacific Fortresses were increasingly difficult to maintain, and the longer range of the B-24 made it more practical anyway in a theater defined by the vast distances to targets.

Due to its specialized nature, 41-2666 evaded retirement despite the damage received on the 16 June 43 mission.[1] Repairs and modifications reversed many of the changes made by the Eager Beavers. The plane was returned to the 8th PRS, and by fall had even returned to combat, flying two missions with the 63rd Bombardment Squadron.[2] By March 1944, though, it had been returned to the US to be used first as a base transport aircraft and then as a heavy bomber trainer, before finally being flown to Albuquerque, New Mexico in August 1945 to be sold as scrap metal.[1]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old 666. |

- #41-2666, Individual Aircraft Record Card, American Air Museum in Britain, retrieved 21 Jan 2019

- "'Old 666' / 'Lucy': A History". Zeamer's Eager Beavers - The Definitive Resource. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Stanaway and Rocker 1999, p. 8.

- Stanaway and Rocker 1999, p. 69.

- "Zeamer's Eager Beavers: The Incredible True Story". Zeamer’s Eager Beavers - The Definitive Resource. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Zeamer 1945, p. 105

- Jay Zeamer flight log

- Murphy 1993, p. 167.

- Murphy 1993, p. 168.

- Murphy 1993, p. 169.

- Gamble 2013, p. 80.

- Zeamer 1945, p. 106

- Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, Item ID C08051658400, pp. 44-45.

- Associated Press (26 March 2007). "Jay Zeamer Jr., 88; pilot won the Medal of Honor in World War II". Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Long Odds (episode)". Dogfights (TV). The History Channel. January 19, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gamble 2013, p. 81.

- Drury and Clavin, p. 267.

- USAF Historical Division's Brief History of the 43rd Bombardment Group, 1940-1952, retrieved 21 Jan 2019

- Stanaway, John, and Rocker, Bob. The Eight Ballers: Eyes of the Fifth Air Force: The 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron in World War. (X Planes of the Third Reich Series). Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 1999. ISBN 978-0764309106

- Murphy, James T., with Feuer, A.B. Skip Bombing. Praeger, 1993. ISBN 978-0275945404

- Zeamer, Jay (January 1945). "There's Always a Way". The American Magazine.

- Zeamer’s Eaver Beavers – The Definitive Resource, Clint Hayes, retrieved 23 Jan 2019

- Gamble, Bruce. Target: Rabaul. Zenith Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7603-4407-1

- Drury, Bob and Clavin, Tom. Lucky 666: The Impossible Mission That Changed the War in the Pacific. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2017. ISBN 978-1-4767-7485-5