On Springfield Mountain

"On Springfield Mountain" or "Springfield Mountain" (Laws G16)[1] is an American ballad which recounts the tragic death of a young man who is bitten by a rattlesnake while mowing a field.[2] Historically, the song refers to the death of Timothy Merrick, who was recorded to have died on August 7, 1761 in Wilbraham, Massachusetts by snakebite. It is commonly included in collections of American folksong, and is one of the earliest known American ballads.[3][4][5][6]

| "(On) Springfield Mountain" | |

|---|---|

Melody and verse to a "Molly type" variation of the ballad | |

| Song | |

| Published | Late 18th or early 19th century |

| Genre | Ballad, Folk song |

The ballad has been cited as representative of elegiac verse tradition which later gained status as folklore throughout the United States. Due to its popularity, there exist many variations of the ballad and its narrative. Although the song is now accompanied by its own distinct melody, early performances of the ballad were sung to other airs, including "Old Hundredth"[7][8] and "Merrily Danced the Quaker's Wife".[9]

Historical basis

Timothy Merrick was born on May 24, 1739 to Lieutenant Thomas Merrick and his wife, Mary. As the story goes, at the age of 22, Timothy Merrick was engaged to be married to his village sweetheart, Sarah Lamb. However, on August 7, 1761, prior to their wedding day, Timothy Merrick set out to mow his father's field and was bitten by a rattlesnake, dying shortly thereafter.

Research efforts by several local historians have uncovered further biographical and historical context surrounding the incident. Charles Merrick claimed Wilbraham, Massachusetts to be the site of the 1761 snakebite fatality.[10] However, the neighboring town of Hampden, Massachusetts also holds a claim to the song's place of origin: the actual farmland where Timothy Merrick was bitten and died was located on the Hampden side of the modern town line, although prior to 1878 Hampden was known as South Wilbraham and considered part of Wilbraham.[11] Chauncey Peck's 1913 History of Wilbraham relates that it occurred "70 to 90 rods southwest of the boy's home,"[12] placing it within current-day Hampden borders.[13] A 1761 record of the Wilbraham town clerk includes a short record of the incident, reading "Lieut Thomas Mirick's only Son dyed, August 7th, 1761, By the Bite of a Ratle Snake, Being 22 years, two months and three days old, and very nigh marridge."[14] Given the rarity of venmous snakes in the region, a 1982 Springfield Union article suggested that Merrick's death was the last recorded snakebite casualty in Massachusetts. However, a reference to another man found to have been killed by a serpent on May 1, 1778 was later discovered by William Meuse in the Wilbraham death records.[15]

There exists some disagreement among folklorists with regards to the ballad's lyrics. Scholar Phillips Barry did not believe the ballad to predate 1825;[16] Tristram Coffin later rejected this claim as short-sighted, and held that the ballad might be derived from older elegiac verse about the incident.[17][18] Other authors note that no written versions were found until 1836 (or 1840, with melody).[19]

Variants and adaptations

The events related in the lyrics have been adapted outside of song, including stage performances and other ballads that include embellished details of the event. Alternative titles include "Ballad of Springfield Mountain",[20] "The Springfield Ballad", "On Springfield Mountains",[21] "The Pizing Sarpent",[22] "The Pesky Sarpent", "Stuttering Song",[23] "The Story of Timothy Mirick", and "Elegy on a/the Young Man Bitten by a Rattlesnake". In variations which feature the character Timothy Mettick, his name is occasionally spelled "Mirick" or "Myrick".[24]

One "entirely serious" version was recorded by George Brown from Mr. Josiah S. Kennison of Townshend, Vermont, and published in Vermont Folk-Songs & Ballads in 1931.[25]

Lyrical variations

Stebbins version

This variant was reported by Rufus Stebbins' Historical Address during the Wilbraham Centennial Celebration of 1863, p. 206. Stebbins, whose family later owned the farm land where the incident is believed to have occurred, asserts that this version is likely the true original exactly as penned by "probable author" Nathan Torrey, but that the lyrics had since been "tampered with" by other authors.[26]

"Elegy on the Young Man Bitten by a Rattlesnake"

On Springfield Mountain there did dwell

A likely youth was knowne full well

Lieutenant Mirick onley son

A likely youth nigh twenty-one

One Friday morning he did go

Into the medow and did mow

A round or two then he did feel

A pisin sarpent at his heel.

When he received his dedly wond

He dropt his sithe a pon the ground

And strate for home wase his intent

Caling aloude stil as he went

Tho all around his voys was hered

But none of his friends to him apiere

They thot it wase some workmen calld

And there poor Timothy alone must fall

So soon his Carful father went

To seek his son with discontent

And there his fond onley son he found

Ded as a stone a pon the ground

And there he lay down sopose to rest

With both his hands Acrost his brest

His mouth and eyes closed fast

And there poor man he slept his last

His father vieude his track with great consarn

Where he had ran across the corn

Uneven tracks where he did go

Did apear to stagger to and frou

The seventh of August sixty one

This fatal axsident was done

Let this a warning be to all

To be Prepared when God does call.

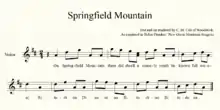

"Molly type" version

In one variation of the ballad published in Flanders's The New Green Mountain Songster and collected by C.M. Cobb, it is sung with melisma on the last syllable of each verse, which is drawn out over two nonsense diphthongs vowels. In addition, this variation features a four-bar refrain at the end of each verse. This later development of the ballad uses characters Tommy Blake and Molly Bland in place of Timothy and Sarah. Molly attempts to suck out the poison and dies in the process.[24][27]

- On Springfield Mountain

- There did dwell

- A comely youth.

- 'Tis known full we-o-al

- Ru tu di nu

- Di nu ni na

- Ti tu di nu

- Ti bu di na

- [...]

- Now Molly had,

- A Ruby lip,

- With which the Poison

- She did si-o-ip

- Ru tu, etc.

- She also had,

- A rotten Tuth,

- In which it struck,

- And killed them both

- Ru tu, etc.[28]

Woody Guthrie version

The song has also found popularity outside of New England folk tradition. Folk singer Woody Guthrie, who claimed his mother sang it to him as a child,[29] covered the song with Sonny Terry, Cisco Houston, and Bess Hawes on the album Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs. This rendition incorporated nonsense lyrics into each verse line, paralleling the frequently accompanied chorus:

- A nice young man-wa-wa-wa-wan lived on a

- hill-I-will-I-will

- And a nice young man-wa-wa-wa-wan, and I

- knowed him well-well-well-well-well

- Come a rood-i rood, a rood-i rood-i ray.[30]

See also

- Rattlesnake Mountain (song), a popular variant of the ballad.

- Fair Charlotte, another cautionary folk ballad situated in New England, about a girl who freezes to death during a sleigh-ride. The two ballads are often cited together as examples of narrative verse representative of obituary tradition.

References

- Laws, G. Malcolm (1964). Native American Balladry: A Descriptive Study and a Bibliographic Syllabus. Philadelphia: The American Folklore Society. p. 220. ISBN 0-292-73500-6.

- Jordan, Philip D. (July–September 1936). "Notes and Queries". Journal of American Folk-Lore. 49 (193): 263–265. JSTOR 535405.

- Downes, Olin; Siegmeister, Elie (1940). A Treasury of American Song. New York: Howell, Soskin & Co. pp. 32–3.

- "New York Folklore 1988

- National Broadcasting Company, Music of the New World: Handbook, Vols 1-2 p. 43

- Toelken, Barre (1979). The Dynamics of Folklore. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 349–50. ISBN 0-395-27068-5.

- Coffin, Tristam (1964). In A Good Tale and a Bonnie Tune. Dallas, Texas: Southern Methodist University Press. pp. 205, 207.

- Meuse, William E. (2012). "Mr. Cunningham's house was built first" : the history of a house and those who lived in it : the who, what, when, where, how & why. 625 Main Street, Hampden, Massachusetts 01036: Hampden Free Public Library. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-59838-272-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Flanders, Helen Hartness; Elizabeth, Ballard; Brown, George; Phillips, Barry (1939). The New Green Mountain Songster. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 161.

- Merrick, Charles; Foster, Philip (1964). History of Wilbraham, U.S.A., 1763-1963. Massachusetts: Polygraphic Company of America.

- Howlett, Carl C. (1958). Early Hampden Massachusetts Its Settlers and The Homes They Built. Yola Guild of the Federated Community Church. pp. 21–2.

- Peck, Chauncey Edwin (1914). The History of Wilbraham, Massachusetts. Wilbraham, Massachusetts. pp. 80–6.

- Carl Howlett, "On Springfield Mountains" in The Country Press Vol 2 No. 11, Nov 21, 1961.

- Meuse 2012, p. 151.

- Meuse 2012, p. 61.

- Davidson, Donald (1972). Still Rebels, Still Yankees: And Other Essays. Louisiana State University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0807124893.

- Limón, José E. (Winter 2007). "Américo Paredes: Ballad Scholar (Phillips Barry Lecture, 2004)". The Journal of American Folklore. 120 (475): 3–4. doi:10.1353/jaf.2007.0019. JSTOR 4137861.

- Coffin 1964.

- The Bay and the River: 1600-1900. Boston University. 1982.

- New York Folklore Vol. 14, 1988, p. 123

- "The Springfield Ballad". The Middlebury Register. Middlebury, Vermont. May 30, 1855. p. 1. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Jordan 1936, p. 118.

- Keefer, Jane (2011). "Folk Music Index". Ibiblio. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- Merrick 1964, p. 311.

- Helen Hartness Flanders; George Brown (1931). Vermont Folk-songs & Ballads. Folklore Associates.

- Meuse 2012, p. 152.

- Flanders 1939, p. 160.

- Flanders 1939, p. 159-60.

- Reuss, Richard A. (Jul–Sep 1970). "Woody Guthrie and His Folk Tradition". The Journal of American Folklore. 83 (329): 284. JSTOR 538806.

- Guthrie, Woody; Seeger, Pete (1989). Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs with Leadbelly, Cisco Houson, Sonny Terry, Bess Hawes liner notes (PDF). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways. pp. 8–9.