Onge

The Onge (also Önge, Ongee, and Öñge) are an indigenous people of Little Andaman, one of the Andaman Islands in India. Traditionally hunter-gatherers, they are one of the Andamanese peoples and are designated as a Scheduled Tribe.[2]

en-iregale | |

|---|---|

A young Onge mother with child taken by Radcliffe Brown in 1905 | |

| Total population | |

| 101[1] (2011 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

western side of Little Andaman Island | |

| Languages | |

| Önge, one of the Ongan languages | |

| Religion | |

| traditional folk religion (animism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Andamanese peoples, particularly Jarawa |

History

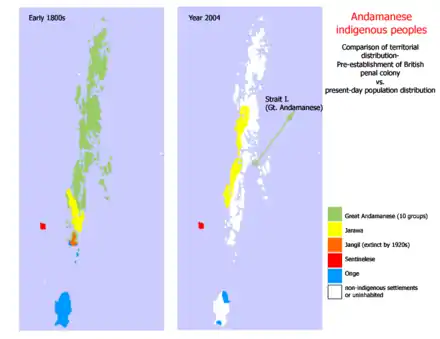

In the 18th century the Onge, or Madhumitha, were distributed across Little Andaman Island and the nearby islands, with some territory and camps established on Rutland Island and the southern tip of South Andaman Island. After they encountered British colonial officers, friendly relations were established with the British Empire in the 1800s through Lieutenant Archibald Blair. British naval officer M. V. Portman described them as the "mildest, most timid, and inoffensive" group of Andamanese people he had encountered.[3][4] By the end of the 19th century they sometimes visited the South and North Brother Islands to catch sea turtles; at the time, those islands seemed to be the boundary between their territory and the range of the Great Andamanese people further north.[4] Today, the surviving members are confined to two reserve camps on Little Andaman, Dugong Creek in the northeast, and South Bay.

The Onge were semi-nomadic and fully dependent on hunting and gathering for food.

The Onge are one of the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands. Together with the other Andamanese tribes and a few other isolated groups elsewhere in Southeast Asia, they comprise the Negrito peoples.

Population

Onge population numbers were substantially reduced in the aftermath of colonisation and settlement, from 672 in 1901 to barely 100.[5]:51[6]

A major cause of the decline in Onge population is the changes in their food habits brought about by their contact with the outside world.[7] The Onge are one of the least fertile people in the world. About 40% of the married couples are sterile. Onge women rarely become pregnant before the age of 28.[8] Infant and child mortality is in the range of 40%.[9] The Onge's net reproductive index is 0.91.[10] The net reproductive index among the Great Andamanese is 1.40.[11]

In 1901, there were 672 Onge; 631 in 1911, 346 in 1921, 250 in 1931, and 150 in 1951.[12][13]

Tsunami

The semi-nomadic Onge have a traditional story that tells of the ground shaking and a great wall of water destroying the land. Taking heed of this story, all 96 tribesmen of the Onge survived the tsunami caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake by taking shelter in the highlands.[14]

Poisoning incident

In December 2008, eight male tribal members died after drinking a toxic liquid – identified as methanol by some sources – that they had apparently mistaken for drinking alcohol.[15] The liquid apparently came from a container that had washed ashore at Dugong Creek near their settlement on the island, but Port Blair authorities ordered an investigation into whether it had originated elsewhere. A further 15 Onge were taken to hospital with at least one critically ill.[16]

With their population estimated at only around 100 before the incident, the director of Survival International described the mass poisoning as a "calamity for the Onge", and warned that any more deaths could "put the survival of the entire tribe in serious danger". Alcohol and drug addiction have in recent years developed into a serious problem for the Onge, adding to the threats to their continued survival posed by outside influences.[16]

Bhopinder Singh, the Lieutenant Governor of the Andaman Islands, ordered an inquiry into the incident.[17]

Language

The Onge speak the Önge language. It is one of two known Ongan languages (South Andamanese languages). Önge used to be spoken throughout Little Andaman as well as in smaller islands to the north, and possibly in the southern tip of South Andaman island. Since the middle of the 19th century, with the arrival of the British in the Andamans, and, after Indian independence, the massive inflow of Indian settlers from the mainland, the number of Onge speakers has steadily declined. However, a moderate increase has been observed in recent years.[18] As of 2006, there were 94 Onge speakers[19] confined to a single settlement in the northeast of Little Andaman Island (see map above), making it an endangered language.

Genetics

A genome-wide study by Reich et al. (2009) found that the Onge Andamanese are most closely related to other Negrito populations in Malaysia and the Philippines. The study further showed that while the Onge are related to modern Indian people, they have none of the admixture from Neolithic Iranian farmers or steppe pastoralists which is widespread on the mainland. From this, they conclude that the Onge are solely descended from one of the ancient populations which contributed to the genetics of modern Indians.[20] According to Chaubey and Endicott (2013) Overall, the Andamanese are more closely related to Southeast Asians (as well as Melanesians and Southeast Asian Negritos) than they are to present-day South Asians.[21] According to Basu et al. (2016), the populations of the Andaman Islands archipelago form a distinct ancestry, which is "coancestral to Oceanic populations".[22]

Analysis of paternal lineages indicates that all Onge carry the Y-DNA Haplogroup D.[23] Maternally, the Onge also exclusively belong to the M clade, bearing the M2 and M4 subclades.[24][20][25] A 2017 study suggests that the Onge are derived from a lineage that trifurcated from East Asians and Australasians in ancient time.[26]

References

- http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/PCA/SC_ST/PCA-A11_Appendix/ST-35-PCA-A11-APPENDIX.xlsx

- "List of notified Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). Census India. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Weber, George. "Maurice Vidal Portman (1861–1935)". The Andamanese (Appendix A – Pioneer Biographies of the British Period to 1947). Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- M. V. Portman (1899), A history of our Relations with the Andamanese, Volume II. Office of the Government Printing, Calcutta, India.

- Pandya, Vishvajit (1993). Above the Forest: A Study of Andamanese Ethnoanemology, Cosmology, and the Power of Ritual. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562971-2.

- "अंडमान में जनजातियों को ख़तरा" [Tribes endangered in the Andamans]. BBC News (in Hindi). 30 December 2004. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

जारवा के 100, ओन्गी के 105, ग्रेट एंडमानिस के 40–45 और सेन्टेलीज़ के क़रीब 250 लोग नेगरीटो कबीले से हैं, जो दक्षिण एशिया की प्राचीनतम जनजाति है [100 of the Jarawa, 105 of the Onge, 40–45 of the Great Andamanese, and about 250 of the Sentinelese belong to the Negrito group which is South Asia's oldest tribal affiliation].

- Devi, L. Dilly (1987). "Sociological Aspects of Food and Nutrition among the Onges of the Little Andaman Island". Ph.D. dissertation, University of Delhi, Delhi

- Mann, Rann Singh (2005). Andaman and Nicobar Tribes Restudied. ISBN 978-81-8324-010-9.

- "Ecocide or Genocide? The Onge in the Andaman Islands". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- A. N. Sharma (2003), Tribal Development in the Andaman Islands, page 64. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi.

- A. N. Sharma (2003), Tribal Development in the Andaman Islands, page 72. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi.

- "Journal of Social Research". 19. Council of Social and Cultural Research, Ranchi University Department of Anthropology, Bihar. 1976. Retrieved 25 November 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Little Andaman: a chronology". Frontline. Chennai, India. 16 (9). 1999. ISSN 0970-1710.

- Budjeryn, Mariana. "And Then Came the Tsunami: Disaster Brings Attention and New Challenges to Asia's Indigenous Peoples". Cultural Survival Quarterly. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- Bhaumik, Subir (9 December 2008). "Alcohol error hits Andamans tribe". BBC News. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- Buncombe, Andrew (12 December 2008). "Washed-up poison bottle kills eight members of island tribe" (online edition). The Independent. London. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- "Inquiry ordered into death of Onge tribesmen". The Hindu. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

- "The Colonisation of Little Andaman Island". Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2013). "Öñge". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (17th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- Reich, David; Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Nick Patterson; Alkes L. Price; Lalji Singh (24 September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian Population History". Nature. 461 (7263): 489–494. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210. PMID 19779445.

- Endicott, Phillip; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer (June 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a Regional Genetic Context: Reexamining the Evidence for an Early Peopling of the Archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1/3): 153–173. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 24297224. S2CID 7774927.

- Basu 2016, p. 1594.

- Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Lalji Singh, Alla G. Reddy, V.Raghavendra Rao, Subhash C. Sehgal, Peter A. Underhill, Melanie Pierson, Ian G. Frame, Erika Hagelberg(2003);Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population ;Current Biology Volume 13, Issue 2, 21 January 2003, Pages 86–93 doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01336-2

- M. Phillip Endicott; Thomas P. Gilbert; Chris Stringer; Carles Lalueza-Fox; Eske Willerslev; Anders J. Hansen; Alan Cooper (2003). "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (1): 178–184. doi:10.1086/345487. PMC 378623. PMID 12478481. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

The HVR‑1 data separate them into two lineages, identified on the Indian mainland ... as M4 and M2 ... The Andamanese M2 contains two haplotypes ... developed in situ, after an early colonization ... Alternatively, it is possible that the haplotypes have become extinct in India or are present at a low frequency and have not yet been sampled, but, in each case, an early settlement of the Andaman Islands by an M2‑bearing population is implied ... The Andaman M4 haplotype ... is still present among populations in India, suggesting it was subject to the late Pleistocene population expansions....

- Moorjani, Priya; Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Nick Patterson; Alkes L. Price; Lalji Singh; David Reich (5 September 2013). "Genetic Evidence for Recent Population Mixture in India". American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (3): 422–438. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. PMC 3769933. PMID 23932107.

- Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (2017). "working model of the deep relationships of diverse modern human genetic lineages outside of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (4): 889–902. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 5400393. PMID 28074030.