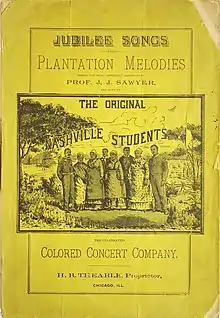

Original Nashville Students

The Original Nashville Students, also referred to as the Original Tennessee Jubilee and Plantation Singers, the Nashville Students, and H. B. Thearle's Nashville Students, were an ensemble of eight or nine African-American jubilee singers. The moniker “jubilee singer” was coined by George White for his a cappella group The Fisk Jubilee Singers. This was primarily a reference to the Jewish year of jubilee described in Leviticus 25.[1] Additionally, jubilation elicits connections with emancipation and liberation, drawing on emotions of nationalist pride from both African American and white audiences. Adopting this title allowed the singers to brand themselves as those who were formerly enslaved, but who had triumphantly risen out of their oppression.

History

The Original Nashville Students, who were neither students nor from Nashville, seem to have formed in Chicago in 1882.[2] As “the Original Tennessee Jubilee and Plantation Singers,” they toured small towns on the western lecture circuit, led by the World Lyceum Bureau and its proprietors H. T. Wilson and Harry B. Thearle. On their 1882 tour, they performed in YMCAs, libraries, town halls, churches, and opera houses. Harry B. Thearle (1858-1914) was born to the prominent minister Reverend Fred G. Thearle, who early in his career had been involved with “colored Sunday schools in the south,”[3] and later managed the Baptist Book Publishing Company. Additionally, he was an active member of the church choir. This appreciation for music and black folk culture seems to have made an impression on his son: as a lyceum agent, one of the first groups he hired was an ensemble of jubilee singers.[4] That appreciation for black folk culture seems to have been passed down to his son, as one of the first groups he hired as a lyceum agent was an ensemble of jubilee singers.

By 1883, the group took on a new name: the Nashville Students, and later added “Original.” There was a dual purpose to this name change: there was an over-saturation of groups with “Tennessee” in their name, and “Original” was meant to distinguish themselves. Perhaps more importantly, “Nashville Students” elicits connections with and parallels to the Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, the originators of jubilee singing.

Music

The eight or nine members of the troupe performed spirituals and plantation sketches. Their program consisted of several parts. The first featured selections of traditional spirituals among other songs, the second featured soloists and a quartet, followed by a sketch in full plantation costume. The performance concluded with a comical musical sketch.

Beginning as early as 1884, the Original Nashville Singers performed under the agency of the prestigious Redpath Lyceum Bureau, with Thearle remaining as their proprietor. The following is an excerpt from that season's program, as reported by Sandra Jean Graham in her book “Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry”:

"Note.-The “NASHVILLE STUDENTS” claim to possess cultivated voices and to be competent to sing what is commonly termed classical music; but it is not their mission, and they leave that field to the white concert companies. But they DO claim to sing the original Jubilee and Plantation Melodies, as sung by the children of bondage in their own peculiar manner in religious and social meetings and on the plantation.

PART FIRST

1. Opening Chorus - Company

2. Keep a moving - Miss Nellie Scott Tipton

3. My Lord is Writing Down Time - Miss Franklin Hawkins

4. Every Day Will Be Sunday, bye and bye - Chas. Moore

5. How I long to go - Aug. L. Wright

6. “Selected” - Miss Helen Sawyer

7. Listen to dem ding dong bells. - W. J. Moon

O, I'll Meet You Dar - Walter Tipton

9. Gospel Train - All Aboard

Piano Selections - Geo. B. McPherson"[5]

This concert program complicates their claim to be singing the “original Jubilee and Plantation Melodies,” since “Listen to Dem Ding Dong Bells” is a novelty song by Jacob J. Sawyer, who was their music director in at least 1884 and 1885, and both “Every Day Will Be Sunday, bye and bye” and “O, I’ll Meet You Dar” are commercial spirituals composed by Sam Lucas, an African American songwriter who had close ties with the Original Nashville Singers. These songs are not in fact “original” jubilee or plantation melodies, they are new compositions with a plantation theme. While many commercial spirituals were exploitative of the student jubilee tradition for comic potential, Lucas's spirituals generally seem to pay homage to the jubilee tradition. Lucas's songs, while not original to the era of slavery, were certainly written in a traditional style, with frequent nods to traditional spirituals. The complication to the Original Nashville Students’ claim to originality or authenticity is less in their choice of repertoire, and more in an early concession to “variety”: a plantation sketch, complete with rustic costumes consisting of calico dresses, overalls, and bandannas. The Original Nashville Students performed these sketches as early as 1886, and also during their 1890-1891 season.[6] While for the most part performing traditional music, the inclusion of a plantation sketch draws a connection to exploitative minstrel shows, which contradicts the true-to-tradition nature of the ensemble in both name (their allusion to the Fisk Jubilee Singers) and repertoire choice. “The Nashville Students successfully incorporated variety entertainment in their programs while maintaining their reputation as concert artists. As the category of jubilee singer loosened, the boundaries between the altruistic and the purely commercial, between the folk and the popular, and between ‘high’ and ‘low’ began to blur.”[7]

Consolidation

The Original Nashville Students came about near the end of a short period of public enthusiasm for jubilee music - the industry was largely worn out by 1890. They were an outlier in that they continued touring through at least the 1890-1891 concert season.[8] According to an excerpt published in Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s book “Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music,” in 1895 the Original Nashville Students consolidated into the Mahara Minstrels, a minstrel company run by W. A. Mahara which toured throughout the southern United States and as far away as Cuba. On July 20, 1895, the New York Clipper reported: “Notes from the Mahara Minstrels,” “The latest addition to the company is the original Nashville Students, eight in number. Mr. Mahara intends on making [them] a strong feature in the free concert given daily by his company. A portable stage will be erected each day in the most prominent street of the cities that they visit, and a performance of pleasing plantation and old time melodies will be rendered.”[9]

Singers

In a companion website to her book “Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry,” Sandra Jean Graham lists the complete personnel of the Original Nashville Students, as she does for over one hundred other jubilee troupes. It reads as follows:

“Personnel in 1885–1886: Helen Sawyer Moon (who sang with the Boston Ideals) and Cornelia Franklin Hawkins, soprano; Fannie Chinn (later a member of Glazier's Jubilee Singers) and Nellie Scott, alto; W. J. Moon and A. G. Wright, tenor; Walter Tipton, baritone; Charles Moore, bass; and George B. McPherson, solo pianist and accompanist.

Personnel given in an 1887 program: Kitty Brown, Cornelia Hawkins, Chas. Moore, Clara Bell, L. E. Pugsley (later of the Tennessee Warblers), Fred. Carey, and Geo. Walley (HTC).

Personnel in 1890, according to the Cleveland Gazette: Cora L. Watson, Clara Bell Carey, Mr. and Mrs. William Carter, Miss Gertie Heathcock, Joseph Hagerman (bass), and John M. Lewis (cited in Abbott and Seroff, Out of Sight, 171).

As Abbott and Seroff point out, in fall 1892, bass singer Joseph Hagerman struck out on his own, forming a new troupe with baritone Ollie C. Hall. After that, Thearle went on to other things, and the troupe was effectively disbanded, although a Freeman column of 28 July 1900 noted that "Thearle's Nashville Students" had just returned from a year's trip through the Pacific (Out of Sight, 171–72).

Ike Simond says the troupe "handled a great many people in its time" and recalls the following members (Old Slack's Reminiscence, 21): Cora Lee Watson, Mr. and Mrs. Fred Cary, Allie Hall, Neal Hawkins, and Ada Woods."[10]

Jacob J. Sawyer served the group as music director from 1884-1885.[11] "Sawyer had a varied career, working with the Hyers sisters combination starting in 1877 and later as pianist and/or music director for the Virginia Jubilee Singers, Haverly’s Minstrels, Sam Lucas’s various jubilee troupes, the Maryland Jubilee Singers, and the Nashville Students. With a body of eighteen instrumental compositions (mazurkas, waltzes, scottisches, polkas, and marches for solo piano), twenty-four vocal songs (eleven of which were commercial spirituals), and six arrangements - published over a mere six years (1879-1885) - he was also one of his generation’s most prolific songwriters."[12]

References

- Graham, Sandra Jean (2018). Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0252041631.

- Graham. Spirituals. p. 238.

- Graham. Spirituals. p. 238.

- Graham. Spirituals. p. 238.

- Graham. Spirituals. pp. 238–239.

- Abbott, Lynn; Seroff, Doug (2002). Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 170. ISBN 978-1604732443.

- Graham. Spirituals. p. 244.

- Abbott; Seroff. Out of Sight. p. 172.

- Abbott; Seroff. Out of Sight. p. 118.

- Graham, Sandra Jean. "Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry: Companion Website". University of Illinois Press. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Schüler, Nico (September 3, 2014) [November 26, 2013]. "Sawyer, Jacob J. [Sawyer, Jacob J.A.]". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Graham. Spirituals. pp. 246–247.