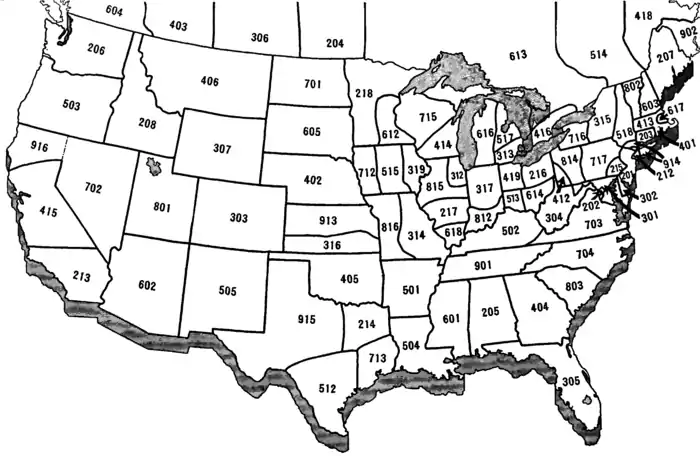

Original North American area codes

The original North American area codes were established by the American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T) in the immediate post-WWII period. The effort of creating a comprehensive and universal, continent-wide telephone numbering plan in North America had the eventual goal of direct distance dialing by telephone subscribers with a uniform destination addressing and call routing system for all public service telephone networks. The initial Nationwide Numbering Plan of 1947 established eighty-six numbering plan areas (NPAs) that principally followed existing U.S. state or Canadian provincial boundaries, but fifteen states and provinces were subdivided further. Forty NPAs were mapped to entire states or provinces. Each NPA was identified by a three digit area code used as a prefix to each local telephone number. The initial system of numbering plan areas and area codes was expanded rapidly in the following decades and established the North American Numbering Plan (NANP).

History

Early in the 20th century, the American and Canadian telephone industry had established criteria and circuits for sending telephone calls across the vast number of local telephone networks on the continent to permit users to call others in many remote places in both countries. By 1930, this resulted in the establishment of the General Toll Switching Plan, a systematic approach with technical specifications, for routing calls between two major classes of routing centers, Regional Centers and Primary Outlets,[1] as well as thousands of minor interchange points and tributaries. Calls were manually forwarded between centers by long-distance operators who used the method of ringdown to command remote operators to accept calls on behalf of customers. This required long call set-up times with several intermediate operators involved. When placing a call, the originating party would typically have to hang up and be called back by an operator once the call was established.

The introduction of the first Western Electric No. 4 Crossbar Switching System in Philadelphia to commercial service, in August 1943,[2] automated the process of forwarding telephone calls between switching centers. For the Bell System this was the first step to let their long-distance operators dial calls directly to potentially far-away telephones.[3] While automatic switching decreased the connection times from up to fifteen minutes to approximately two minutes for calls between far-away locations, each intermediate operator still had to determine special routing codes unique to their location for each call. To make a nationwide dialing network a practical reality, and to prepare for eventual direct distance dialing (DDD) by subscribers, a uniform nationwide numbering plan was needed so that each telephone on the continent had a unique address that could be used independently from where a call originated. Such methodology is called destination routing.

With this goal, AT&T developed a new system called Nationwide Operator Toll Dialing during the 1940s. The effort proceeded with periodical communications to the general telecommunication industry via the Dial Interexchange Committee of the United States Independent Telephone Association.[4] The planning came to a conclusion in October 1947, when results were presented to wider industry bodies. The new numbering plan became known as the nationwide numbering plan, and by 1975 it was known as the North American Numbering Plan, as efforts were in progress to expand the system beyond the United States and Canada.

Central office prefixes

Building a nationwide network in which anyone can dial another telephone required a systematic numbering system that was easy to understand and communicate to the general public. Local telephone numbers varied greatly across the country, from two or three digits in small communities, to seven in the large cities. Based on the precedent and experience with the large-city dial systems in the nation, the designers set out to standardize every local telephone network in the nation to seven-digit local telephone numbers. This required no or only a few changes in the nation's largest cities. The large automatic dial switching systems were designed to provide service for up to ten thousand subscriber lines. Therefore, each telephone connected to such a switch had a four-digit line or station number.

For calling a telephone connected to another switching system in the same city or in a nearby community, a routing prefix was used that was dialed before the line number. Central office prefixes had already been used in the cities' dial systems since the 1920s, and were typically dialed by subscribers as the initial letters of the exchange name, but only the largest of cities used three digits or letters. This practice and familiarity was preserved in the initial formulation of the new numbering plan, but was standardized to a format of using two letters and one digit in the prefix, resulting in the format 2L–5N (two letters and five numerals) for the subscriber telephone number.[5]

This conversion required the addition of extra digits to the existing central office prefix. For example, the Atlantic City, New Jersey, telephone number 4-5876 was converted to AT4-5876 in the 1950s. Complete replacement of existing prefixes was necessary in the case of conflicts with another office in the state. Duplication of central office names or an identical mapping of two different names to digits was not uncommon. In practice, the conversion of the nation to this numbering plan took decades to accomplish and was not complete before the alphanumeric number format was abandoned in the 1960s in favor of all-number calling (ANC).

Numbering plan areas

Initial concepts for a nationwide numbering plan anticipated by 1945 to divide the continent into between fifty and seventy-five numbering plan areas.[6] Considering this size of the network, a unique two-digit code for each numbering plan area (NPA) would have been sufficient. However, AT&T wanted to preserve existing dialing practices by only dialing the local number for local calls; it was therefore necessary to distinguish the NPA codes from central office codes. Central office codes could not have the digits 0 and 1 in the first two positions, because no letters were mapped to those to represent exchange names. This was the opportunity for distinction, but only when used in the second position, because switching systems already suppressed single loop interruption (corresponding to 1) automatically, and 0 was used to reach an operator or long-distance desk.[5]

Therefore, numbering plan area codes, often called just area codes, were defined to have three digits, with the middle digit being 0 or 1. Area codes with the middle digit 0 were assigned to numbering plan areas that comprised an entire state or province, while jurisdictions with multiple plan areas received area codes having 1 as the second digit.

No codes of the forms N00, N10, and N11 (N is 2 through 9) occurred in the original area code allocation, leaving a total of 136 possible combinations. The series N00 was later used for non-geographic numbers, starting with intrastate toll-free 800 numbers in 1966.[7] N10 numbers became teletypewriter exchanges, and N11 were used later for special services, such as information and emergency services.

The geographic layout of numbering plan areas across the North American continent was chosen primarily according to national, state, and territorial boundaries in Canada and the United States.[8] While originally considered, no numbering plan area in the United States included more than a single state, but in Canada NPA 902 comprised all three territories of The Maritimes in the far east. The largest states, and some states with suitable call routing infrastructure were divided into smaller entities, resulting in fifteen states and provinces that were subdivided further, creating 46 NPAs. Forty NPAs were assigned to entire states or provinces.

The territories of the United States, which included Alaska, and Hawaii, did not receive area codes at first.[8]

| 1947 division of the North American continent into 86 numbering plan areas[8] |

|---|

|

Initially, the area codes were used for nationwide Operator Toll Dialing by long-distance operators who dialed them for routing trunk calls between toll offices. This replaced the previous methods of ringdown forwarding between intermediate operators.[8] Preparations proceeded for end-customer direct distance dialing (DDD) by establishing special automatic toll-switching centers based on new technology development for the No. 4 Crossbar Switching System, first installed in Philadelphia in 1943.

While the first customer-dialed call using an area code was made on November 10, 1951, from Englewood, New Jersey, to Alameda, California,[9][10] it was not until the 1960s that direct distance dialing was common in most cities.

Area code assignment

The original configuration of the North American Numbering Plan assigned eighty-six area codes in October 1947, one each to every numbering plan area.

| Area code | Country/State ID | State, province, or region |

|---|---|---|

| 201 | US:NJ | New Jersey |

| 202 | US:DC | District of Columbia |

| 203 | US:CT | Connecticut |

| 204 | CA:MB | Manitoba |

| 205 | US:AL | Alabama |

| 206 | US:WA | Washington |

| 207 | US:ME | Maine |

| 208 | US:ID | Idaho |

| 212 | US:NY | New York (New York City) |

| 213 | US:CA | California (Southern California, including Los Angeles) |

| 214 | US:TX | Texas (northeastern Texas, including Dallas/Fort Worth) |

| 215 | US:PA | Pennsylvania (southeastern Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia) |

| 216 | US:OH | Ohio (northeastern Ohio, including Cleveland) |

| 217 | US:IL | Illinois (central) |

| 218 | US:MN | Minnesota (except southeastern part of state) |

| 301 | US:MD | Maryland |

| 302 | US:DE | Delaware |

| 303 | US:CO | Colorado |

| 304 | US:WV | West Virginia |

| 305 | US:FL | Florida |

| 306 | CA:SK | Saskatchewan |

| 307 | US:WY | Wyoming |

| 312 | US:IL | Illinois (Chicago metropolitan area) |

| 313 | US:MI | Michigan (southeast Michigan, including Detroit) |

| 314 | US:MO | Missouri (eastern Missouri, including St. Louis) |

| 315 | US:NY | New York (central upstate New York, including Syracuse) |

| 316 | US:KS | Kansas (southern half of Kansas) |

| 317 | US:IN | Indiana (northern two-thirds of Indiana, including Indianapolis) |

| 319 | US:IA | Iowa (eastern third of Iowa) |

| 401 | US:RI | Rhode Island |

| 402 | US:NE | Nebraska |

| 403 | CA:AB | Alberta |

| 404 | US:GA | Georgia |

| 405 | US:OK | Oklahoma |

| 406 | US:MT | Montana |

| 412 | US:PA | Pennsylvania (western Pennsylvania, including Pittsburgh) |

| 413 | US:MA | Massachusetts (western Massachusetts, including Springfield) |

| 414 | US:WI | Wisconsin (southern and northeastern Wisconsin, including Milwaukee) |

| 415 | US:CA | California (northern/central California, including San Francisco and Sacramento) |

| 416 | CA:ON | Ontario (southern portion from Cobourg to Kitchener, including Toronto) |

| 418 | CA:QC | Quebec (eastern half of Quebec, including Québec City) |

| 419 | US:OH | Ohio (northwest Ohio, including Toledo) |

| 501 | US:AR | Arkansas |

| 502 | US:KY | Kentucky |

| 503 | US:OR | Oregon |

| 504 | US:LA | Louisiana |

| 505 | US:NM | New Mexico |

| 512 | US:TX | Texas (central and southern Texas, including Austin and San Antonio) |

| 513 | US:OH | Ohio (southwest Ohio, including Cincinnati) |

| 514 | CA:QC | Quebec (western half of Quebec, including Montreal) |

| 515 | US:IA | Iowa (central Iowa, including Des Moines) |

| 517 | US:MI | Michigan (south-central portion of Lower Peninsula, including Lansing) |

| 518 | US:NY | New York (northeastern New York, including Albany) |

| 601 | US:MS | Mississippi |

| 602 | US:AZ | Arizona |

| 603 | US:NH | New Hampshire |

| 604 | CA:BC | British Columbia |

| 605 | US:SD | South Dakota |

| 612 | US:MN | Minnesota (southeastern portion, including Minneapolis) |

| 613 | CA:ON | Ontario (all except a southern portion covering Oshawa-Toronto-Kitchener) |

| 614 | US:OH | Ohio (southeast, including Columbus) |

| 616 | US:MI | Michigan (Grand Rapids, Upper Peninsula, western portion of Lower Peninsula) |

| 617 | US:MA | Massachusetts (eastern Massachusetts, including Boston) |

| 618 | US:IL | Illinois (southern Illinois, including East St. Louis and Carbondale) |

| 701 | US:ND | North Dakota |

| 702 | US:NV | Nevada |

| 703 | US:VA | Virginia |

| 704 | US:NC | North Carolina |

| 712 | US:IA | Iowa (western third, including Sioux City) |

| 713 | US:TX | Texas (southeastern Texas, including Houston) |

| 715 | US:WI | Wisconsin (northern Wisconsin) |

| 716 | US:NY | New York (western New York, including Buffalo and Rochester) |

| 717 | US:PA | Pennsylvania (eastern half, except for the Delaware and Lehigh Valleys) |

| 801 | US:UT | Utah |

| 802 | US:VT | Vermont |

| 803 | US:SC | South Carolina |

| 812 | US:IN | Indiana (southern Indiana) |

| 814 | US:PA | Pennsylvania (northwestern and central Pennsylvania) |

| 815 | US:IL | Illinois (northern Illinois, except Chicago and Quad Cities) |

| 816 | US:MO | Missouri (northwestern Missouri, including Kansas City) |

| 901 | US:TN | Tennessee |

| 902 | CA:NS,PE,NB | Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick |

| 913 | US:KS | Kansas (northern half of Kansas) |

| 914 | US:NY | New York (southern New York, including Long Island, but excluding New York City) |

| 915 | US:TX | Texas (western Texas, including El Paso) |

| 916 | US:CA | California (northern California, but not including Sacramento) |

Assignment plan

| States with more than two NPAs | |

|---|---|

| New York | 212, 315, 518, 716, 914 |

| Illinois | 217, 312, 618, 815 |

| Ohio | 216, 419, 513, 614 |

| Pennsylvania | 215, 412, 717, 814 |

| Texas | 214, 512, 713, 915 |

| California | 213, 415, 916 |

| Iowa | 319, 515, 712 |

| Michigan | 313, 517, 616 |

| States and provinces with two NPAs | |

| Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts,

Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin, Ontario, Quebec | |

The number of central offices that could be effectively installed in a plan with two letters and one digit for the central office code was expected to be approximately 500, because acceptable names for central offices had to be selected carefully to avoid miscommunication. States that required this many offices had to be divided into multiple smaller areas. But size or population was not the sole criterion for division. A very important aspect was the existing infrastructure for call routing, which had developed in preceding decades independently of state boundaries. Since traffic between numbering plan areas would require special Class-4 toll switching systems, divisions attempted to avoid cutting busy toll traffic routes, so that most toll traffic remained within an area, and outgoing traffic from one area would not be tributary to toll offices in an adjacent area.[11][5] On the other hand, it was already recognized in 1930 that too little granularity in the allocation pattern introduced expensive traffic back-haul requirements, conceivably resulting in congestion of the routes to the centers.[1]

These considerations led to the configuration that was publicized in October 1947, which divided New York state into five areas, the most of any state. Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas were assigned four area codes each, and California, Iowa, and Michigan received three. Eight states and provinces were split into two NPAs. The pattern of this official assignment of area codes is illustrated in the following tabulation, separated into U.S. states or Canadian provinces with a single area code, and those with multiple NPA assignments.

| Single-NPA states and provinces | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20N | 30N | 40N | 50N | 60N | 70N | 80N | 90N |

| 1 | 201 NJ | 301 MD | 401 RI | 501 AR | 601 MS | 701 ND | 801 UT | 901 TN |

| 2 | 202 DC | 302 DE | 402 NE | 502 KY | 602 AZ | 702 NV | 802 VT | 902 NB NS PE |

| 3 | 203 CT | 303 CO | 403 AB | 503 OR | 603 NH | 703 VA | 803 SC | |

| 4 | 204 MB | 304 WV | 404 GA | 504 LA | 604 BC | 704 NC | ||

| 5 | 205 AL | 305 FL | 405 OK | 505 NM | 605 SD | |||

| 6 | 206 WA | 306 SK | 406 MT | |||||

| 7 | 207 ME | 307 WY | ||||||

| 8 | 208 ID | |||||||

| 9 | ||||||||

| Multi-NPA states and provinces | ||||||||

| N | 21N | 31N | 41N | 51N | 61N | 71N | 81N | 91N |

| 2 | 212 NY | 312 IL | 412 PA | 512 TX | 612 MN | 712 IA | 812 IN | |

| 3 | 213 CA | 313 MI | 413 MA | 513 OH | 613 ON | 713 TX | 913 KS | |

| 4 | 214 TX | 314 MO | 414 WI | 514 QC | 614 OH | 814 PA | 914 NY | |

| 5 | 215 PA | 315 NY | 415 CA | 515 IA | 715 WI | 815 IL | 915 TX | |

| 6 | 216 OH | 316 KS | 416 ON | 616 MI | 716 NY | 816 MO | 916 CA | |

| 7 | 217 IL | 317 IN | 517 MI | 617 MA | 717 PA | |||

| 8 | 218 MN | 418 QC | 518 NY | 618 IL | ||||

| 9 | 319 IA | 419 OH | ||||||

In the group of multiple-NPA states, the area codes first assigned (upper left corner) may be identified with the toll switching locations of the Regional Centers established in the General Toll Switching Plan of 1929:[1] New York City (212), Los Angeles (213), Dallas (214), Chicago (312), St. Louis (314), and San Francisco (415), supplemented by newer systems in Detroit (313), serving the busy toll route to Toronto,[12] and in Philadelphia (215), which had been chosen for the first cut-over into commercial service of a No. 4 Crossbar toll switch in 1943.[13] The remaining Regional Centers in Denver (303) and Atlanta (404) were located in states with just a single area code each.

Expansion

As the implementation of the new numbering plan commenced, and the planning and design of detailed routing infrastructure proceeded, several numbering plan areas were redrawn or added in following years, usually before any direct distance dialing was available to the public. In 1948, Indiana received an extra area code (219) for its Chicago suburbs in the west. In 1950, southwest Missouri received area code 417, which reduced the extent of the Kansas City numbering plan area and thus provided more prefixes in that population center. In 1951, the State of New York gained area code 516 on Long Island, and Southern California received area code 714, to reduce the numbering plan area of Los Angeles. After the successful initial trials of direct distance dialing in Englewood, NJ of late 1951,[9] expansion of the numbering plan accelerated with four new codes in 1953, seven in 1954, and by the end of the decade thirty-one additional area codes had been created over the initial allotment of 1947.[14] to satisfy the post-war surge in demand for telephone service. In 1960, AT&T engineers, while already estimating that the capacity of the numbering plan would be exceeded by 1975,[14] prepared the nation for the next major step in the evolution of the network by eliminating central office names, and introducing all-number calling (ANC). ANC increased the number of central office prefixes possible in each numbering plan area from 540 to an eventual maximum of 792 after the introduction of interchangeable central office codes in the 1970s.

In popular culture

Numerous media outlets and blog-style online publication have commented on the history of the area codes.[15] Such reports invariably state that area codes were assigned by a principle of counting pulses (clicks) of the rotary dial, which were minimized for the large metropolitan area, such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, while assigning codes with many pulses to sparsely populated areas. However, no authoritative sources for this method are quoted, and none of the original Bell System documents support this. The concept appears to agree only for a few of the largest of cities, which were already designated Regional Centers for switching in the plan of 1929, and no correlation exists beyond those.

References

- H. S. Osborne, A General Switching Plan for Telephone Toll Service, Bell System Technical Journal Vol 9 (3) p.429 (1930)

- Howard L. Hosford, A Dial Switching System for Toll Calls, Bell Telephone Magazine Vol 22 p.289 (Winter 1943/1944)

- James J. Pilliod, Harold L. Ryan, Operator Toll Dialing—A New Long Distance Method, Bell Telephone Magazine, Volume 26, p.101 (1945).

- Norris F.E. (Chairman) USITA, Telephony Vol.130 (1946-01-12) Nationwide Operator Toll Dialing

- AT&T, Notes on Nationwide Dialing (1955)

- F. F. Shipley, Nation-Wide Dialing, Bell Laboratories Record Vol 23(10) pp.368 (October 1945)

- "Atlanta Telephone History". Atlantatelephonehistory.info. 1968-06-29. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- Ralph Mabbs, Nation-Wide Operator Toll Dialing—the Coming Way, Bell Telephone Magazine 1947 p.180

- AT&T Corporation, 1951: First Direct-Dial Transcontinental Telephone Call, backed up by the Internet Archive as of 2007-01-07, accessed 2020-08-25

- Staff. "Who's on First? Why, New Jersey, of Course", The New York Times, 1979-07-22, accessed 2020-08-26

- W.H. Nunn, Nationwide Numbering Plan, Bell System Technical Journal 31(5), 851 (1952)

- H. S. Osborne, A General Switching Plan for Telephone Toll Service, Bell System Technical Journal Vol 9 (3), July 1930, p.431

- A. B. Clark, H. S. Osborne, Automatic Switching for Nationwide Telephone Service, Bell System Technical Journal Vol 31(5) pp.823 (1952)

- William A. Sinks, New Telephone Numbers for Tomorrow's Telephones, Bell Telephone Magazine Vol.40 pp.6–15 (Winter 1959/60)

- See for example: Garber, Megan (2014-02-13). "Our Numbered Days: The Evolution of the Area Code". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-08-27.