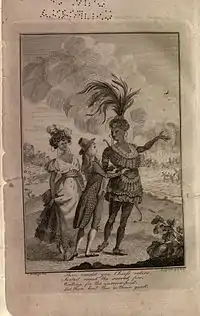

Ouabi; Or the Virtues of Nature: An Indian Tale in Four Cantos

Ouábi; Or the Virtues of Nature: An Indian Tale in Four Cantos is a narrative poem by Sarah Wentworth Morton that tells the tale of a love triangle between two Native Americans and one white man. The narrative is one of the first works to use Native American themes in American verse. Morton included many notes about Indian councils, war feasts, the Mississippi River, marriage ceremonies, and the Indian concept of revenge.

The Native Americans in this poem are shown to have sympathy savage mode with literary devices and an admiration for their farm setting. Ouábi also touches on a more modern problem: the passing of simple American virtues weighed down by lavishness and classiness.

Background

Sarah Wentworth Morton had her work published in 1790 under the name Philenia. Ouábi is not written in the traditional style of most stories, rather it is written in the form of a narrative poem in four parts. The narrative is the first of its kind with an Indian as the hero.[2]

Plot summary

The narrative poem tells the story of a woman, Azákia, belonging to the Illinois Indian Tribe. Azákia is first introduced to the reader while a man from the rival Huron Tribe is attempting to rape her. Azákia is then rescued by a white man, Celario, which spurs a love triangle between Celario, Azákia, and her husband, Ouábi. This triangle is not only of love, but also of friendship, as Ouábi and Celario actually generate a very good friendship.

Celario lusts after Azákia, and she has feelings for him, but she knows she must stay loyal to her husband, Ouábi. The Illinois sachem allows Celario to go to war with him, to prove himself worthy of his wife, Azákia. Celario is injured in battle and sent back to the settlement with Azákia. Ultimately, Ouábi realizes that the love Celario has for Azákia is unmatched by the love he has for her. Ouábi relinquishes his "marriage" to Azákia so she and Celario can be together as was truly meant to be.[3]

Author

_-_Worcester_Art_Museum_-_IMG_7688.JPG.webp)

Sarah Wentworth Morton was born into wealth and power in the year 1759. She remained under cultural protection for most of her life. She was a very attractive woman, as shown in Stuart's portrait. It is said that she was somewhat stuck-up, a snob and that she had an unsophisticated outlook. Most important to understanding the narrative is the story of her family relationships. Later on, she married Perez Morton, a young lawyer who later became Speaker of the House in Massachusetts. When she was married, her husband almost destroyed his own career seducing his spouse's sister, Frances. Frances had a child by him but after reconciling with Sarah and hearing Perez deny any responsibility for the affair and child, Frances poisoned herself, committing suicide.[4]

Wentworth Morton only published one work under her given name. Others were published under pseudonyms. Initially her pseudonym was Constantia, but another poet had begun writing and submitting works to papers, and claimed that the prior works were hers also. Due to this second Constantia, Wentworth changed her nom de plum to Constantia Philenia, and then to just Philenia.[5] This change of name may also have something to do with Wentworth Morton attempting to prove her patriotism. It is thought that this name comes from her love and respect for the Philanei brothers whom loved their country so much that they were actually willing to be buried alive for it.[6] "I am induced to hope that the attempting a subject wholly American will in some respect entitle me to the partial eye of the patriot; that, as a young author, I shall be received with tenderness, and, as an involuntary one, be criticized with candor".[1] This quote indicates the desire to be viewed as truly patriotic, and her aspiration to be an American poet and author.

Analysis

The tale resembles the story of her own life with her spouse, Perez Morton, and sister, Frances. The two stories ends in exactly the same fashion, suicide. In real life, Frances commits suicide because what she has done is wrong. In her narrative poem, the great Illinois sachem Ouábi allows himself to die so that Celario and Azákia may be together. While the suicides differentiate slightly, they both are performed in order to allow partners to be together as they should be. Ouábi makes this virtuous suicide look more like a long-standing tradition in the tribe rather than something imported from elsewhere. Suicide is truly the most interesting aspect of the narrative poem. All three main characters take their turn offering their lives for one another. Celario goes to war for Ouábi, offering his life for him and Azákia at the same time. Ouábi then dies for Celario and Azákia so they can be together. Lastly, Azákia, overcome with the sadness Ouábi's death considers killing herself for him, and the only reason she restrains is because she promised Celario she would not act so drastically. These life offerings show suicide is proof of natural virtue, and a presumably nonaggressive for the white man to win.[3]

Other intriguing concepts in ‘’Ouábi’’ are the ideas of homosocial relationships and gender differentiations in Indian culture. The fact that Celario was banished from his people because of a duel gone wrong in which somebody died who was not supposed to and that he came to a culture which is dedicated to hand-to-hand combat and personal revenge allows Morton to truly critique modern Anglo-American masculinity, dedicated to adulterous debauchery. This also allows Morton to compare the masculinity of Ouábi and Celario to the femininity of Azákia. While the idea of revenge plays a large part in masculinity and it is an outward action that can be shown, the feminine aspect of melancholia is the exact opposite. It has no outward action. It produces strong mental hyperactivity. The opening scene generates the view that Azákia is truly the one who suffers with and for the male characters. Women are expected to have this type of attitude. That they should mourn when men mourn and mourn for them even if they do not. This is also shown when Azákia is contemplating suicide because Ouábi killed himself for her.[3] The idea of suicide comes from her dreams and fantasies that just are not real. “Her feelings have the same transparent integrity as theirs and her psychological life is far richer, but she is never instrumental”.[3]

References

- Morton, Sarah Wentworth (1790). Ouábi; or The Virtues of Nature: An Indian Tale in Four Cantos. Boston, MA: Faust's Statue.

- Nitchie, Elizabeth (July 1918). "The Longer Narrative Poems of America 1775-1875". The Sewanee Review. 26 (3): 283–300. JSTOR 27533124.

- Ellison, Julie (September 1993). "Race and Sensibility in the Early Republic: Ann Eliza Bleecker and Sarah Wentworth Morton". American Literature. 65 (3): 445–474. doi:10.2307/2927389. JSTOR 2927389.

- Schriftgiesser, Karl (April 1932). "Philenia: The Life and Works of Sarah Wentworth Morton, 1759-1846 by Emily Pendleton; Milton Ellis; Sarah Wentworth Morton". The New England Quarterly. 5 (2): 368–370. doi:10.2307/359626. JSTOR 359626.

- "Dictionary of Literary Biography". Thomson Gale. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- Harris, Paul S. (1964). "Gilbert Stuart and a Portrait of Mrs. Sarah Apthorp Morton". Winterthur Portfolio. 1: 198–220. doi:10.1086/495745. JSTOR 1180477.