Overman Committee

The Overman Committee was a special subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. Between September 1918 and June 1919, it investigated German and Bolshevik elements in the United States. It was an early forerunner of the better known House Un-American Activities Committee, and represented the first congressional committee investigation of communism.

The committee's final report was released in June 1919. It reported on German propaganda, Bolshevism, and other "un-American activities" in the United States and on likely effects of communism's implementation in the United States. It described German, but not communist, propaganda efforts. The committee's report and hearings were instrumental in fostering anti-Bolshevik opinion.

Background

World War I, in which the United States and its allies fought - among other Central Powers - the German Empire, raised concern about the German threat to the United States. The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 were passed in response.[1]

In the Russian Revolution of 1917 the Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Russian monarchy and instituted Marxism-Leninism. Many Americans were worried about the revolution's ideas infiltrating the United States, a phenomenon later named the Red Scare of 1919–20.[2]

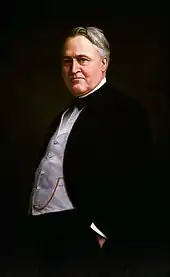

The Overman Committee was formally an ad-hoc subcommittee of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, but had no formal name.[3] It was chaired by Senator Lee Slater Overman and also included Senators Knute Nelson of Minnesota, Thomas Sterling of South Dakota, William H. King of Utah, and Josiah O. Wolcott of Delaware.[4]

Initial investigation

The committee was authorized by Senate Resolution 307 on September 19, 1918 to investigate charges against the United States Brewers Association (USBA) and allied interests. Brewing institutions had been largely founded by German immigrants in the mid-19th century, who brought with them knowledge and techniques for brewing beer.[5][6] The Committee interpreted this mission to mean a general probe into German propaganda and pro-German activities in the United States.[7] Hearings were mandated after A. Mitchell Palmer, the federal government's Alien Property Custodian responsible for German-owned property in the U.S., testified in September 1918 that the USBA and the rest of the overwhelmingly German[8] liquor industry harbored pro-German sentiments.[9] He stated that "German brewers of America, in association with the United States Brewers' Association" had attempted "to buy a great newspaper" and "control the government of State and Nation", had generally been "unpatriotic", and had "pro-German sympathies".[6]

—Senator William H. King

December 9, 1918[10]

Hearings began September 27, 1918, shortly before the end of World War I.[6] Nearly four dozen witnesses testified.[11] Many were agents of the Bureau of Investigations (BOI), the predecessor of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The agents, controversially[12][13] and usually erroneously,[12] implicated high-profile American citizens as pro-German, using the fallacy of guilt by association.[14] For example, the Bureau chief labeled some people pro-German because they had insubstantial and non-ideological[15] acquaintance with German agents.[12] Others were accused because their names were discovered in the notebooks of suspected German agents, of whom they had never heard.[12]

Many attacked the BOI's actions. The Committee heard testimony that it had not conducted basic background checks of the accused and had not read source material it presented to the committee.[15] Committee members criticized its testimony as "purely hearsay".[13][16]

Expansion of investigation

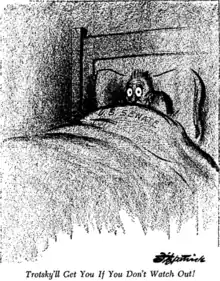

A political cartoon drawn by Daniel R. Fitzpatrick published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 6, 1919, satirizing the Senate's expansion of the Overman Committee's authority two days earlier[17]

On February 4, 1919, the Senate unanimously passed Senator Thomas J. Walsh's[18] Senate Resolution 439, expanding the committee's investigations to include "any efforts being made to propagate in this country the principles of any party exercising or claiming to exercise any authority in Russia" and "any effort to incite the overthrow of the Government of this country".[19] This decision followed months of sensational daily press coverage[20] of revolutionary events abroad and Bolshevik meetings and events in the United States,[21] which increased anti-radical public opinion.[22] Reports that some of these meetings were attended by Congressmen caused further outrage.[21] One meeting in particular, held at the Poli Theater in Washington, DC, was widely controversial because of a speech given by Albert Rhys Williams, a popular Congregationalist minister,[23] who allegedly said, "America sooner or later is going to accept the Soviet Government."[24]

Archibald E. Stevenson, a New York attorney with ties to the Justice Department, likely a "volunteer spy",[25] testified on January 22, 1919, during the German phase of the subcommittee's work. He said that anti-war and anti-draft activism during World War I, which he described as "pro-German" activity, had now transformed into propaganda "developing sympathy for the Bolshevik movement.".[26] The United States' wartime enemy, though defeated, had exported an ideology that ruled Russia and threatened America anew. "The Bolsheviki movement is a branch of the revolutionary socialism of Germany. It had its origin in the philosophy of Marx and its leaders were Germans."[27] He cited the propaganda efforts of John Reed and gave many examples from the foreign press. He told the Senators, "We have found money coming into this country from Russia."[28] Stevenson has been described by historian Regin Schmidt as a "driving force" behind the growth of anti-Bolshevism in the United States.[29]

The final catalyst for the expansion of the investigation was the Seattle General Strike, which began the day before the Senate passed Resolution 439.[24] This confluence of events led members of Congress to believe that the alleged German-Bolshevist link and Bolshevist threat to the United States were real.[30]

Bolshevism hearings

Mr WILLIAMS: I think that probably not more than 50 per cent of the Russian people can read and write.[31]"

The Overman Committee's hearings on Bolshevism lasted from February 11 to March 10, 1919.[32] More than two dozen witnesses were interviewed.[33] About two-thirds were violently anti-Bolshevik and advocated for military intervention in Russia.[34] Some were refugees of the Russian Diaspora—many former government officials[35]—who left Russia because of Bolshevism.[36] The overriding theme was the social chaos the Revolution had brought,[35] but three sub-themes were also frequent: anti-Americanism among American intelligentsia, the relationship between Jews and Communist Russia, and the "nationalization" of women after the Soviet revolution.

Stevenson produced a list of 200—later reduced to 62—alleged communist professors in the United States.[30] Like lists of names provided during the German propaganda hearings, this list provoked an outcry.[37] Stevenson declared universities to be breeding grounds of sedition, and that institutions of higher learning were "festering masses of pure atheism" and "the grossest kind of materialism".[38] Ambassador to Russia David R. Francis stated that the Bolsheviks were killing everybody "who wears a white collar or who is educated and who is not a Bolshevik."[39]

Another recurring theme at the hearings was the relationship between Jews and communists in Russia. One Methodist preacher stated that nineteen out of twenty communists were Jews;[40] others said the Red Army was composed mainly of former East Side New York Jews.[41] However, after criticism from Jewish organizations,[42] Senator Overman clarified that the committee was discussing "apostate" Jews only, defined by witness George Simons as "one who has given up the faith of his fathers or forefathers."[43]

A third frequent theme was the "free love" and "nationalization" of women allegedly occurring in Soviet Russia.[44] Witnesses described an orgy in which there was no "respect for virtuous women";[45] others who testified, including those who had been in Russia during the Revolution,[45] denied this.[46] After one witness read a Soviet decree saying that Russian women had the "right to choose from among men",[47] Senator Sterling threw up his hands and declared that this was a negation of "free love".[46] However, another decree was produced stating, "A girl having reached her eighteenth year is to be announced as the property of the state."[48]

The Senators were particularly interested in how Bolshevism had united many disparate elements on the left, including anarchists and socialists of many types,[49] "providing a common platform for all these radical groups to stand on."[50] Senator Knute Nelson of Minnesota responded: "Then they have really rendered a service to the various classes of progressives and reformers that we have here in this country."[50] Other witnesses described the horrors of the revolution in Russia and speculated on the consequences of a comparable revolution in the United States: the imposition of atheism, the seizure of newspapers, assaults on banks and the abolition of the insurance industry. The Senators heard various views of women in Russia, including claims that women were made the property of the state.[51]

Final report

The committee's final report detailed its investigations into German propaganda, Bolshevism, and other "un-American activities" in the United States and predicted effects of communism's implementation in the United States.[53] It was endorsed unanimously. Released in June 1919,[52] it was over 35,000 words long,[5] and was compiled by Major Edwin Lowry Humes.[53]

The Committee did little to demonstrate the extent of communist activity in the United States.[34] In its analysis of what would happen if capitalism were overthrown and replaced by communism,[54] it warned of widespread misery and hunger, the confiscation of and nationalization of all property, and the beginning of "a program of terror, fear, extermination, and destruction."[55] Anti-Bolshevik public sentiment surged after release of the report and ensuing publicity.[22]

German investigation

Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, Karl Boy-Ed, Franz von Papen, Dr. Heinrich Albert, and Franz von Rintelen, among others, were Germans investigated for producing propaganda. All were previously evicted from the United States for being part of a German espionage ring. The United States Brewers Association, the National German-American Alliance, and the Hamburg-American steamship line were investigated. The final report concluded that these organizations, through financial support, bribes, boycotts, and coercion, sought to control the press, elections, and public opinion.[5]

Bolshevism investigation

—The Committee's final report[52]

The report described the Communist system in Russia as "a reign of terror unparalleled in the history of modern civilization".[56] It concluded that instituting Marxism-Leninism in the United States would result in "the destruction of life and property", the deprivation "of the right to participate in affairs of government", and the "further suppress[ion]" of a "substantial rural portion of the population." Furthermore, there would be an "opening of the doors of all prisons and penitentiaries".[52] It would result in the "seizure and confiscation of the 22,896 newspapers and periodicals in the United States" and "complete control of all banking institutions and their assets". "One of the most appalling and far reaching consequences ... would be found in the confiscation and liquidation of ... life insurance companies." The report also criticized "the atheism that permeates the whole Russian dictatorship"; "they have denounced our religion and our God as 'lies'."[52]

Despite the report's rhetoric and the headlines it produced, the report contained little evidence of communist propaganda in the United States or its effect on American labor.[34]

Recommendations

The report's main recommendations included deporting alien radicals and enacting peacetime sedition laws.[57] Other recommendations included strict regulation of the manufacture, distribution, and possession of high explosives; control and regulation of foreign language publications,[58] and the creation of patriotic propaganda.[57]

Press reaction

The press reveled in the investigation and the final report, referring to the Russians as "assassins and madmen," "human scum," "crime mad," and "beasts."[59] The occasional testimony by some who viewed the Russian Revolution favorably lacked the punch of its critics. One extended headline in February read:[60]

- Says Riffraff, Not the Toilers, Rule in Russia

- American Manager of Great American Plant There Tells Experiences to Senators

- Outsiders Seized Power

- Came Back from Other Countries and are Growing Rich at People's Expense

- Factories Being Ruined

- 60,000,000 Rubles Spent in Three Months at One Plant to Produce 400,000 Worth of Goods

And one day later:[61]

- Bolshevism Bared by R.E. Simmons

- Former Agent in Russia of Commerce Department Concludes his Story to Senators

- Women are 'Nationalized'

- Official Decrees Reveal Depths of Degradation to Which They are Subjected by Reds

- Germans Profit by Chaos

- Factories and Mills are Closed and the Machinery Sold to Them for a Song

On the release of the final report, newspapers printed sensational articles with headlines in capital letters: "Red Peril Here", "Plan Bloody Revolution", and "Want Washington Government Overturned."[62]

Criticism

Critics denounced the committee as a "propaganda apparatus" to stoke anti-German and anti-Soviet fears, feeding the Red Scare[63] and spreading misinformation about Soviet Russia.[32]

The Committee attracted criticism from the public for its perceived overreach, and especially for publishing the names of those accused of association with communist organizations. One woman from Kentucky wrote to Senator Overman on behalf of her sister, who had been accused by Archibald Stevenson, criticizing the committee for its "brutal as well as stupid misuse of power" and "gross and cruel injustice to men and women the full peer in intellect, character and patriotism of any member of the United States Senate".[37] The committee was compared to "a witch hunt" in one exchange with a witness.[64]

Aftermath

The Overman Committee did not achieve any lasting reforms.[65] However, the panel's sensationalism played a decisive role in increasing America's fears during the Red Scare of 1919–20.[54] Its investigations served as a blueprint for the Department of Justice's anti-radical Palmer raids late in the year. These were led by Attorney General Palmer, whose testimony about German brewers had been the catalyst for the committee's creation.[57]

On May 1, 1919, a month after the committee's hearings ended, a bomb was mailed to Overman's home, one of a series of letter bombs sent to prominent Americans in the 1919 United States anarchist bombings. It was intercepted before it reached its target.[66]

Later investigative committees

The Overman Committee was the first of many Congressional committees to investigate communism.[8] In the aftermath of the Overman Committee's report, the New York State Legislature established the Lusk Committee, which operated from June 1919 to January 1920,[67][68] Archibald E. Stevenson was its chief counsel and one of its witnesses.[69][70] Unlike the Overman Committee, the Lusk Committee was active in raiding suspect organizations.[68]

The Overman Committee was an early forerunner of the better known House Un-American Activities Committee, which was created 20 years later.[22]

References

- Venzon, Anne Cipriano; Paul L. Miles (1999). The United States in the First World War. Taylor & Francis. p. 536. ISBN 9780815333531.

- Murray, 15-7

- Senate Judiciary Committee Photo Gallery Archived 2009-07-01 at the Wayback Machine . United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 2

- "Overman Report Accuses Brewers". The New York Times. June 15, 1919. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Congress, Brewing and Liquor Interests, volume 1, p. 3

- Hagedorn, p. 53

- Mittelman, p. 83

- Congress, Brewing and Liquor Interests, volume 1, pp. 3–4

- Congress, Brewing and Liquor Interests, volume 2, p. 1596

- Congress, Brewing and Liquor Interests, volume 1, p. 1387 and volume 2, p. 1385

- Lowenthal, p. 37

- Lowenthal, p. 40

- Lowenthal, p. 39

- Lowenthal, p. 38

- Congress, Brewing and Liquor Interests, volume 2, p. 2453

- Murray, p. 96

- Schmidt, p. 140

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 6

- Clark, p. 16

- "Senate Orders Reds Here Investigated" (PDF). The New York Times. February 5, 1919. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Schmidt, p. 136

- Murray, p. 46

- Murray, p. 94

- Hagedorn 54, 58

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 12-4; Powers, 20

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 14; Lowenthal, 49

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 19, 29

- Schmidt, p. 138

- Hagedorn, p. 55

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 606

- Clark, p. 15

- Hagedorn, p. 147

- Murray, p. 95

- Hagedorn, p. 129

- McFadden, p. 296

- Lowenthal, p. 60

- Pfannestiel, p. 13

- Murray, p. 97

- Powers, p. 47

- Hagedorn, p. 148

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 381

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 116

- Nielsen, p. 30

- Lowenthal, p. 51

- Lowenthal, p. 52

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 354

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 475

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 14-8

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 34

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, 475

- "Senators Tell What Bolshevism in America Means" (PDF). The New York Times. June 15, 1919. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- "Drastic Red Bill Ready for Senate" (PDF). The New York Times. June 12, 1919. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Schmidt, p. 144

- Schmidt, pp. 145–146

- Schmidt, p. 145

- McCormick, p. 92

- "Senators Denounce Lawlessness". Casa Grande Valley Dispatch. July 18, 1919. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Murray, 97

- "Says Riffraff, not the toilers, rule in Russia". New York Times. February 17, 1919. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- "Bolshevism bared by R.E. Simmons". New York Times. February 18, 1919. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Murray, 98

- Sproule, pp. 122–123

- United States Congress, Bolshevik Propaganda, p. 893

- Pfannestiel, p. 132

- "Find More Bombs Sent in the Mails; One to Overman" (PDF). The New York Times. May 2, 1919. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Pfannestiel, p. xi

- Nielsen, p. 15

- Hagedorn, p. 231

- Schmidt, p. 139

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Clark, Evans (2008) [1920]. Facts and Fabrications About Soviet Russia. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 9780554588193.

- United States Senate, Committee on the Judiciary. Brewing and Liquor Interests and German Propaganda: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Sixty-fifth Congress, Second and Third Sessions, Pursuant to S. Res. 307. volume 1, volume 2. Govt. print. off., 1919. Original from the University of Michigan.

- United States Senate, Committee on the Judiciary (1919). Bolshevik Propaganda: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Sixty-fifth Congress, Third Session and Thereafter, Pursuant to S. Res. 439 and 469. February 11, 1919, to March 10, 1919. Govt. print. off., 1919. Original from the University of Michigan.

Secondary sources

- Hagedorn, Ann (2007). Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743243711.

- Lowenthal, Max (1950). Federal Bureau of Investigation. New York: William Sloane Associates, Inc. ISBN 0-8371-5755-2.

- McCormick, Charles H. (1993). Seeing Reds: Federal Surveillance of Radicals in the Pittsburgh Mill District, 1917–1921. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 9780195071870.

- McFadden, David W. (2003). Alternative paths: Soviets and Americans, 1917–1920. Univ of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822958215.

- Mittelman, Amy (2008). Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. Algora Publishing. ISBN 9780875865737.

- Murray, Robert K. (2009). Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816658336.

- Nielsen, Kim E. (2001). Un-American Womanhood: Antiradicalism, Antifeminism, and the First Red Scare. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 9780814208823.

- Pfannestiel, Todd J. (2003). Rethinking the Red Scare: The Lusk Committee and New York's Crusade Against Radicalism, 1919–1923. Routledge. ISBN 9780415947671.

- Powers, Richard Gid (1998). Not without honor: the history of American anticommunism. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300074703.

- Schmidt, Regin (2000). Red Scare: FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the United States, 1919–1943. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788772895819.

- Sproule, J. Michael (1997). Propaganda and Democracy: The American Experience of Media and Mass Persuasion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521470223.

External links

- Volume 1 and volume 2 of the committee's hearings on the brewing industry and German propaganda, from the United States Congress via Google Books

- volume 1 of the committee's hearings on Bolshevik propaganda], from the United States Congress via Google Books

- Excerpt from the committee's Final Report. New York Times: "Senators Tell What Bolshevism in America Means," June 15, 1919, accessed February 24, 2010