Pestivirus

Pestivirus is a genus of viruses, in the family Flaviviridae. Viruses in the genus Pestivirus infect mammals, including members of the family Bovidae (which includes cattle, sheep, and goats) and the family Suidae (which includes various species of swine). Currently, 11 species are placed in this genus, including the type species Pestivirus A. Diseases associated with this genus include: hemorrhagic syndromes, abortion, and fatal mucosal disease.[1][2]

| Pestivirus | |

|---|---|

| |

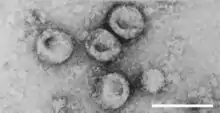

| Virions of Pestivirus sp. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Flasuviricetes |

| Order: | Amarillovirales |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Pestivirus |

| Type species | |

| Pestivirus A | |

| Species | |

| |

Structure

Viruses in Pestivirus are enveloped, with spherical geometries. Their diameter is around 50 nm. Genomes are linear and not segmented, around 12kb in length.[1]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pestivirus | Icosahedral-like | Pseudo T=3 | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Lifecycle

Entry into the host cell is achieved by attachment of the viral envelope protein E to host receptors, which mediates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Replication follows the positive stranded RNA virus replication model. Positive-stranded RNA virus transcription is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by viral initiation. The virus exits the host cell by budding. Mammals serve as the natural hosts. Transmission routes are parental.[1]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pestivirus | Mammals | None | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Secretion | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Vertical: parental |

Genome

Pestivirus viruses have a single strand of positive-sense RNA (i.e. RNA which can be directly translated into viral proteins) that is around 12.5 kilobases (kb) long (equal to the length of 12,500 nucleotides). Sometimes, virions (individual virus particles) contain sections of an animal's genome that have been duplicated, though this is not normally the case. No Poly-A is found on the 3' end of the genome. (This means that these viruses have no post-transcriptional modifications, and have simple RNA genomes.) The genome contains RNA to encode both structural and nonstructural proteins. The molecular biology of pestiviruses shares many similarities and peculiarities with the human hepaciviruses. Genome organisation and translation strategy are highly similar for the members of both genera. For BVDV, frequently nonhomologous RNA recombination events lead to the appearance of genetically distinct viruses that are lethal to the host.[3]

Transmission and prevention

Pestivirus A is widespread in Australia, mainly in cattle. Some adult cattle are immune to the disease, while others are lifelong carriers. If a foetus becomes infected within the first three to four months of gestation, then it will fail to develop antibodies towards the virus. In these cases, the animals often die before birth or shortly after. It is spread very easily among feedlot cattle as nasal secretions and close contact spread the disease, and animals with infected mucous membranes give off millions of particles of BVDV a day.

Symptoms of Pestivirus infection include diarrhoea, respiratory problems, and bleeding disorders.

Pestivirus A vaccines exist and the correct vaccine strain should be given, depending on the herd's location and the endemic strain in that region. This vaccination must be given regularly to maintain immunity.

Species

- Pestivirus A or Bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 (BVDV-1), causes Bovine viral diarrhea and Mucosal disease

- Pestivirus B or Bovine viral diarrhea virus 2 or (BVDV-2), causes Bovine viral diarrhea and Mucosal disease

- Pestivirus C or Classical swine fever virus (CSFV), causes Classical swine fever

- Pestivirus D or Border disease virus (BDV), causes Border disease

- Pestivirus E or pronghorn pestivirus

- Pestivirus F or Bungowannah virus

- Pestivirus G or giraffe pestivirus

- Pestivirus H or Hobi-like pestivirus

- Pestivirus I or Aydin-like pestivirus

- Pestivirus J or rat pestivirus

- Pestivirus K or atypical porcine pestivirus

- (Dongyang pangolin virus, DYPV)[4]

See also

References

- "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ICTV. "Virus Taxonomy: 2018b Release". Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Rumenapf and Thiel (2008). "Molecular Biology of Pestiviruses". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- Loeffelholz, Michael J.; Fenwick, Bradley W. (26 August 2020). "Taxonomic Changes for Human and Animal Viruses, 2018 to 2020". Journal of Clinical Microbiology: JCM.01932–20, jcm, JCM.01932–20v1. doi:10.1128/JCM.01932-20.