Phantoscope

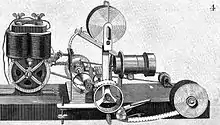

The Phantoscope was a film projection machine, a creation of Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. In the early 1890, Jenkins began creating the projector. He later met Thomas Armat, who provided financial backing and assisted with necessary modifications The two inventors unveiled their modified projector at the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, in September 1895.

Their machine was the first projector to allow each still frame of the film to be illuminated long enough before advancing to the next frame sequence. This was different from Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope, which simply ran a loop of film with successive images of a moving scene through the camera shutter, which gave a jumbled blur of motion. The Phantoscope, by pausing on each frame long enough for the brain to register a clear single picture, but replacing each frame in sequence fast enough (less than a tenth of a second), produced a smooth and true moving picture. It is from this concept that the entire motion-picture industry has grown.[1]

On September 25, 1895, the two inventors began presenting their completed Phantoscopes at the Cotton States Exposition. Their presentation continued for the next eighteen days, during which the increased strain causes conflicts. Tensions escalated when, on October 13th, Jenkins borrowed one of their three completed Phantoscope. He intended to present the invention in his hometown of Indiana, and promised to return the machine by October 25th. He did not, and instead, remained in Indiana[2]

Armat decided to leave the exhibit with their remaining Phantoscope, after a fire destroyed several exhibits and another of their Phantoscopes. What followed was a lengthy court battle in which Jenkins sought a solo patent, but was denied, resulting in Jenkins receiving a solo patent for his initial projector and Armat for the modified version. After the issue was settled, Armat sold his patent to Thomas Alva Edison.[3]

Jenkins continued improving the projector and created motion picture cameras that were eventually used for broadcasting to home receivers by radio waves, or what we know today as, television. Mechanically he broadcast the first television pictures and owned the first commercially licensed television station in the United States.

The Franklin Institute later awarded a gold medal to Jenkins for his invention as the world's first practical movie projector.

References

- Tube: The Invention of Television, David E. Fisher and Marshal Jon Fisher, 1996

- Gosser, H. Mark (1988). "The Armat-Jenkins Dispute and the Museums". Film History. 2 (1): 1–12. ISSN 0892-2160.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved 2009-08-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Kinetoscope at Machine_History.Com