Pharaoh's daughter (Exodus)

The Pharaoh's daughter (Hebrew: בַּת־פַּרְעֹה, lit. 'daughter of Pharaoh') in the story of the finding of Moses in the biblical Book of Exodus is an important, albeit minor, figure in Abrahamic religions. Though some variations of her story exist, the general consensus among Jews, Christians, and Muslims is that she is the adoptive mother of the prophet Moses. Muslims identify her with Asiya, the Great Royal Wife of the pharaoh. In either version, she saved Moses from certain death from both the Nile river and from the Pharaoh. As she ensured the well-being of Moses throughout his early life, she played an essential role in lifting the Hebrew slaves out of bondage in Egypt, their journey to the Promised Land, and the establishment of the Ten Commandments.

| Pharaoh's daughter | |

|---|---|

Finding of Moses in the Dura-Europos synagogue, c. AD 244 | |

| First appearance | Book of Genesis |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Thermouthis (birth name, Judaism) Bithiah (adopted name, Judaism) Merris (Christianity) Merrhoe (Christianity) Asiya (Islam) |

| Spouse | Mered |

| Children | Moses (adoptive) |

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion (formerly) Yahwism (convert) |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

Portrayal

Her name

The Book of Exodus (Exodus 2:5) does not give a name to Pharaoh's daughter, or to her father; she is referred to in Hebrew as simply the Bat-Paroh[1] (Hebrew: בת־פרעה), a Hebrew phrase that literally translates to "daughter of Pharaoh." The Book of Jubilees (Jubilees 47:5) and Josephus both name her as Thermouthis (Greek: Θερμουθις), also transliterated as Tharmuth and Thermutis, the Greek name of Renenutet, the Egyptian snake deity.[2][3][4][5] Meanwhile, Leviticus Rabbah (Leviticus Rabbah 1:3) and the Books of Chronicles (1 Chronicles 4:18) refer to her as Bit-Yah (Hebrew: בתיה, lit. 'daughter of Yahweh'), also transliterated as Batyah and Bithiah, and it is written that she is given the name for her adoption of Moses, that because she had made Moses her son, Yahweh would make her his daughter.[6] Also in the Books of Chronicles (1 Chronicles 4:18), she is called ha-yehudiyyah (Hebrew: הַיְהֻדִיָּ֗ה, lit. 'the Jewess'), which some English translations of the Bible treat as a given name, Jehudijah (Hebrew: יהודיה, romanized: yehudiyyah, lit. 'Jewess'), notably the King James Version, but the word is actually an appelative, there to indicate that Pharaoh's daughter was no longer a pagan.[7][8] In Christianity, she is also named as Merris and Merrhoe, and in Islam, she is named Asiya (Arabic: آسيا), Asiyah (Arabic: آسية), and Asiya bint Muzahim (Arabic: آسيا بنت مزاحم).[9][10]

In Judeo-Christianity

In the Judeo-Christian narrative, Pharaoh's daughter first appears in the Book of Exodus, in Exodus 2:5-10. The passage describes her discovery of the Hebrew child, Moses, in the rushes of the Nile River and her willful defiance of her father's orders that all male Hebrew children be slain, instead taking the child, whom she knows to be a Hebrew, and raising him as her own son. The Talmud and the Midrash Vayosha provide some additional backstory to the event, saying that she had visited the Nile that morning not to bathe for the purpose of hygiene but for ritual purification, treating the river as if it were a mikveh, as she had grown tired of people's idolatrous ways, and that she first sought to nurse Moses herself but he would not take her milk and so, she called for a Hebrew wet nurse, who so happened to be Moses' biological mother, Jochebed.[11][12][13][14] Rabbinic literature tells a significantly different take on the events that day, portraying Pharaoh's daughter as having suffered from a skin disease, the pain of which only the cold waters of the Nile could relieve, and that these lesions healed when she found Moses. It also describes an encounter with the archangel Gabriel, who kills two of her handmaidens for trying to dissuade her from rescuing Moses.[15] After Moses is weaned, Pharaoh's daughter gives him his name, purportedly taken from the word māšāh (Hebrew: מָשָׁה, lit. 'to draw'), because she drew him from the water, but some modern scholars disagree with the Biblical etymology of the name, believing it to have been based on the Egyptian root m-s, meaning "son" or "born of," a popular element in Egyptian names (e. g. Ramesses. Thutmose) used in conjunction with a namesake deity.[16][17] In her later years, Pharaoh's daughter devotes herself to Moses, and to Yahweh; she celebrates the first Passover Seder with Moses in the slaves' quarters and for that, her firstborn is the only Egyptian to survive the final of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and leaves Egypt with him for the Promised Land. In the Books of Chronicles, (1 Chronicles 4:18), she is said to have married a member of the Tribe of Judah, Mered, and to have had children with him, and she is referred to as a Jewess, indicating that she had accepted Yahweh as her own god.[18][19] Furthermore, the Jewish rabbis claim that, in the Book of Proverbs (Proverbs 31:15), she is praised in Woman of Valor. Further, the Midrash teaches that because of her devotion to Yahweh and her adoption of Moses, she was one of those who entered heaven alive.[20]

Now the daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe at the river, and her maidens walked beside the river; she saw the basket among the reeds and sent her maid to fetch it. When she opened it she saw the child; and lo, the babe was crying. She took pity on him and said, "This is one of the Hebrews' children." Then his sister said to Pharaoh's daughter, "Shall I go and call you a nurse from the Hebrew women to nurse the child for you?" And Pharaoh's daughter said to her, "Go." So the girl went and called the child's mother. And Pharaoh's daughter said to her, "Take this child away, and nurse him for me, and I will give you your wages." So the woman took the child and nursed him. And the child grew, and she brought him to Pharaoh's daughter, and he became her son; and she named him Moses, for she said, "Because I drew him out of the water."

— RSV, Exodus 2:5-10

In Islam

In contrast to her story as portrayed in Judaism and Christianity, in Islam, she is known as Asiya (in the Hadith) and the Pharoah's wife (in the Quran). Also, she does not draw Moses from the Nile, her servants do, and Pharaoh, having learned of the boy's existence, seeks to kill him but Asiya intervenes and Pharaoh changes his mind, allowing the boy to live. Mirroring the Judeo-Christian story, Jochebed is called to Pharaoh's palace to act as a wet nurse for him but then, her story, as told by Islam, deviates from the Judeo-Christian version once more, with Asiya being tortured to death at the hands of Pharaoh for professing a belief in the god of Allah.[21]

Art and culture

In the 1956 English-language epic film, The Ten Commandments, Pharaoh's daughter is referred to as Bithiah, and she is the daughter of Ramesses I, the founding pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, and sister to his successor, Seti I. She is portrayed as a young widow, childless, who believes the baby Moses to be a gift to her from the Egyptian gods and is determined to raise him, despite her servant's assertions that the child is a Levite, not an Egyptian. This is in stark contrast to the Biblical telling of the story, as Bithiah had forsaken the gods of Egypt when she happened upon Moses and so, she would not have seen him as a gift from them. In the latter half of the film, Bithiah is shown to be a pious individual, though sympathetic to her fellow Egyptians, who suffer at Pharaoh's stubbornness. She leaves the luxury and safety of her palatial home to reunite with Moses, in the slaves' quarters of the city, and celebrates with him the first Passover Seder. She then accompanies the Israelites to Canaan and, in Moses' absence, is one of the few who refuse to participate in the worship of the Golden calf. She is portrayed by Nina Foch.

In the 1998 English-language animated film, The Prince of Egypt, Pharaoh's daughter is depicted as Queen Tuya, a fictionalized version of Tuya, the queen consort of Seti I, the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. The reason for this change is likely because at the time of production, Ramesses II, also Ramesses the Great, her son with Seti I, was still a popular candidate among theologians for the historical counterpart of the pharaoh mentioned in the Book of Exodus as having caused the Plagues of Egypt for his refusal to liberate the Hebrews from bondage. Additionally, Pharaoh's daughter, in this film, is portrayed as the wife of Pharaoh, rather than his daughter, and is never shown to renounce her idolatrous beliefs or reunite with Moses following his return from Midian, both central parts to her character within Judaism and Christianity, perhaps to simplify the familial connection and plot line for the film's intended child audience. The character is voiced by Helen Mirren, with her singing voice provided by Linda Dee Shayne.

The Moses Chronicles, a novel-trilogy by H. B. Moore, includes Pharaoh's daughter as a character named Bithiah. Parts of the story are written from her perspective.[22]

The 1935 opera Porgy and Bess song It Ain't Necessarily So (George and Ira Gershwin), mentions Pharaoh's daughter finding baby Moses.[23]

Gallery

- Pharaoh's daughter

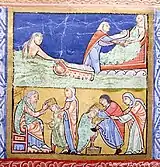

12th century

12th century Moses Saved from the Waters (c. 1556), Bernaert de Rijckere

Moses Saved from the Waters (c. 1556), Bernaert de Rijckere.jpg.webp) Moses Saved from the Waters (1633), Orazio Gentileschi

Moses Saved from the Waters (1633), Orazio Gentileschi The Finding of Moses (17th century), Andrea Celesti

The Finding of Moses (17th century), Andrea Celesti The Finding of Moses (1740), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

The Finding of Moses (1740), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo The Finding of Moses (1862), Frederick Goodall

The Finding of Moses (1862), Frederick Goodall Moses Saved from the Waters (1894), Jacques Clement Wagrez

Moses Saved from the Waters (1894), Jacques Clement Wagrez Pharaoh's Daughter Receives the Mother of Moses (c. 1900), James Tissot

Pharaoh's Daughter Receives the Mother of Moses (c. 1900), James Tissot

References

- "The Story of Batyah (Bithiah) - A Transformed Identity". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- Flusser David, and Shua Amorai-Stark. (1993). ""The Goddess Thermuthis, Moses, and Artapanus." Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 3": 217–33. JSTOR 40753100. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 9,5

- "Thermuthis – History's Women". Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- "Renenutet | Ancient Egypt Online". Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- "Daughter of Pharaoh: Midrash and Aggadah | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- "BITHIAH - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Jehudijah Definition and Meaning - Bible Dictionary". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- Commentary on Hexameron MPG 18.785

- Preparation for the Gospel 9.27

- "The Story of Batyah (Bithiah) - A Transformed Identity". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- Flusser David, and Shua Amorai-Stark. (1993). ""The Goddess Thermuthis, Moses, and Artapanus." Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 3": 217–33. JSTOR 40753100. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 9,5

- "Thermuthis – History's Women". Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- "Renenutet | Ancient Egypt Online". Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- "Was Moses' Name Egyptian?". www.bibleodyssey.org. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Strong's Hebrew: 4871. מָשָׁה (mashah) -- to draw". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- "The Story of Batyah (Bithiah) - A Transformed Identity". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- Flusser David, and Shua Amorai-Stark. (1993). ""The Goddess Thermuthis, Moses, and Artapanus." Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 3": 217–33. JSTOR 40753100. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Segal, Rabbi Arthur (2010-08-11). "RABBI ARTHUR SEGAL: JEWISH RENEWAL: Jabez the Yahudahite". Rabbi Arthur Segal. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- Shahada Sharelle Abdul Haqq (2012). Noble Women of Faith: Asiya, Mary, Khadija, Fatima (illustrated ed.). Tughra Books. ISBN 978-1597842686.

- "Book review: 'Bondage' is an engaging first book in Moses Chronicles series". Deseret News. Aug 1, 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Seven Against Thebes. Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 111. ISBN 9780195070071.

Bibliography

- Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1972, Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Jewish Encyclopedia.com

- Bithiah. (n.d.). Hitchcock's Bible Names Dictionary. Retrieved January 28, 2008, from Dictionary.com website:

0