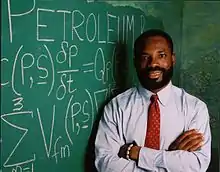

Philip Emeagwali

Philip Emeagwali (born 23 August 1954) is a Nigerian computer scientist.[1] He won the 1989 Gordon Bell Prize for price-performance in high-performance computing applications, in an oil reservoir modeling calculation using a novel mathematical formulation and implementation.[2][3]

Philip Emeagwali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 23, 1954 |

| Nationality | Nigerian |

| Alma mater | George Washington University School of Engineering and Applied Science Oregon State University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Computer science |

Biography

Philip Emeagwali was born in Akure, Nigeria on 23 August 1954.[4] He was raised in Onitsha in the South Eastern part of Nigeria. His early schooling was suspended in 1967 as a result of the Nigerian Civil War. At age 13, he served in the Biafran army. After the war he completed high-school equivalence through self-study.[5]

Later on He married Dale Brown Emeagwali, a noted African-American microbiologist.[6]

Education

He traveled to the United States to study under a scholarship following completion of a correspondence course at the University of London. He received a bachelor's degree in mathematics from Oregon State University in 1977.[7] He later moved to Washington D.C., receiving in 1986 a master's degree from George Washington University in ocean and marine engineering, and a second master's in applied mathematics from the University of Maryland.[8] Next magazine suggested that Emeagwali claimed to have further degrees.[9][10] During this time, he worked as a civil engineer at the Bureau of Land Reclamation in Wyoming.

Court case and the denial of degree

Emeagwali studied for a Ph.D. degree from the University of Michigan from 1987 through 1991. His thesis was not accepted by a committee of internal and external examiners and thus he was not awarded the degree.[11] Emeagwali filed a court challenge, stating that the decision was a violation of his civil rights and that the university had discriminated against him in several ways because of his race. The court challenge was dismissed, as was an appeal to the Michigan state Court of Appeals.[12][13][14]

Supercomputing

Emeagwali received the 1989 Gordon Bell Prize for an application of the CM-2 massively-parallel computer. The application used computational fluid dynamics for oil-reservoir modeling. He received a prize in "price/performance" category, with a performance figure of about 400 Mflops/$1M.[15] The winner in the "performance" category, was also the winner of the Price/performance category, but unable to receive two prizes. Mobil Research and Thinking Machines, used the CM-2 for seismic data processing and achieved the higher ratio of 500 Mflops/$1M. The judges decided on one award per entry.[3][2] His method involved each microprocessor communicating with six neighbors.[10]

Emeagwali's simulation was the first program to apply a pseudo-time approach to reservoir modeling.

Accolades

- Price/performance–1989 Gordon Bell Prize, IEEE ($1,000 prize)[3]

- New African "35th-greatest African (and greatest African scientist) of all time"[16]

He was cited by Bill Clinton as an example of what Nigerians can achieve when given the opportunity[17] and is frequently featured in popular press articles for Black History Month.[18][10]

Selected publications

- Emeagwali, P. (2003). How do we reverse the brain drain. speech given at.[19]

- Emeagwali, P. (1997). Can Nigeria leapfrog into the information age. In World Igbo Congress. New York: August.

See also

References

- Ndiokwere, Nathaniel I. (1998). Search for Greener Pastures: Igbo and African Experience. Indiana University. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-575-0294-50.

- "Gordon Bell Prize Winners". www.sc2000.org. sc2000 Conference. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- "Special Report 1989 Gordon Bell Prize". IEEE. pp. 100–104, 110. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Hamilton, Janice (2003). Nigeria in Pictures. Lerner Publishing Group. p. 70. ISBN 0822503735.

- Braimah, Ayodale (2017-12-31). "Philip Emeagwali (1954- ) •". Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- African Americans in Science: Institutions. ABC-CLIO. 2008. ISBN 978-1851099986.

- "Philip Emeagwali: African American Inventor". www.myblackhistory.net. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- "Black History- Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University2020". www.famu.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- "Emeagwali's insistence on degrees muddles defence". Next. November 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011.

- Gray, Madison. "Philip Emeagwali, A Calculating Move". Time Magazine. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Philip Emeagwali – Nigerian British Awards". Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "PHILIP EMEAGWALI V UNIV OF MICH BOARD OF REGENTS". Justia Law. 1999-10-29. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- "Dr. Phillip Emeagwali born". African American Registry. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "How Philip Emeagwali Lied His Way To Fame". Sahara Reporters. 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Clifford, Igbo. "Philip Emeagwali Biography, Early Life, Education, Businesses, Inventions, Net Worth And More". Information Guide Africa. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Your 100 Greatest Africans of all time", New African, August 2004 Archived July 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Bill Clinton, Remarks to a Joint Session of the Nigerian National Assembly in Abuja, August 2000(transcript) Archived December 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "CNNfyi.com - Chasing the Dream". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- The reverse brain drain : Afghan-American Diaspora in post-conflict peacebuilding and reconstruction. University of Arizona Libraries. 2003. doi:10.2458/azu_acku_pamphlet_jz5584_a33_r494_2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philip Emeagwali. |

- emeagwali.com – Emeagwali's personal website.

- Digital Giants: Philip Emeagwali (BBC)

- Biography of Emeagwali from IEEE (Archive, as of May 26, 2009).