Plasma acceleration

Plasma acceleration is a technique for accelerating charged particles, such as electrons, positrons, and ions, using the electric field associated with electron plasma wave or other high-gradient plasma structures (like shock and sheath fields). The plasma acceleration structures are created either using ultra-short laser pulses or energetic particle beams that are matched to the plasma parameters. These techniques offer a way to build high performance particle accelerators of much smaller size than conventional devices. The basic concepts of plasma acceleration and its possibilities were originally conceived by Toshiki Tajima and Prof. John M. Dawson of UCLA in 1979.[1] The initial experimental designs for a "wakefield" accelerator were conceived at UCLA by Prof. Chan Joshi et al.[2] Current experimental devices show accelerating gradients several orders of magnitude better than current particle accelerators over very short distances, and about one order of magnitude better (1 GeV/m[3] vs 0.1 GeV/m for an RF accelerator[4]) at the one meter scale.

Plasma accelerators have immense promise for innovation of affordable and compact accelerators for various applications ranging from high energy physics to medical and industrial applications. Medical applications include betatron and free-electron light sources for diagnostics or radiation therapy and protons sources for hadron therapy. Plasma accelerators generally use wakefields generated by plasma density waves. However, plasma accelerators can operate in many different regimes depending upon the characteristics of the plasmas used.

For example, an experimental laser plasma accelerator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory accelerates electrons to 1 GeV over about 3.3 cm (5.4x1020 gn),[5] and one conventional accelerator (highest electron energy accelerator) at SLAC requires 64 m to reach the same energy. Similarly, using plasmas an energy gain of more than 40 GeV was achieved using the SLAC SLC beam (42 GeV) in just 85 cm using a plasma wakefield accelerator (8.9x1020 gn).[6] Once fully developed, the technology could replace many of the traditional RF accelerators currently found in particle colliders, hospitals, and research facilities.

Finally, the plasma acceleration would not be complete if the ion acceleration during the expansion of a plasma into a vacuum were not also mentioned.This process occurs, for example, in the intense laser-solid target interaction and is often referred to as the target normal sheath acceleration. Responsible for the spiky, fast ion front of the expanding plasma is an ion wave breaking process that takes place in the initial phase and is described by the Sack-Schamel equation.

History

The Texas Petawatt laser facility at the University of Texas at Austin accelerated electrons to 2 GeV over about 2 cm (1.6x1021 gn).[7] This record was broken (by more than 2x) in 2014 by the scientists at the BELLA (laser) Center at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, when they produced electron beams up to 4.25 GeV.[8]

In late 2014, researchers from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory using the Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET) published proof of the viability of plasma acceleration technology. It was shown to be able to achieve 400 to 500 times higher energy transfer compared to a general linear accelerator design.[9][10]

A proof-of-principle plasma wakefield accelerator experiment using a 400 GeV proton beam from the Super Proton Synchrotron is currently operating at CERN.[11] The experiment, named AWAKE, started experiments at the end of 2016.[12]

In August 2020 scientists reported the achievement of a milestone in the development of laser-plasma accelerators and demonstrate their longest stable operation of 30 hours.[13][14][15][16][17]

Concept

A plasma consists of a fluid of positive and negative charged particles, generally created by heating or photo-ionizing (direct / tunneling / multi-photon / barrier-suppression) a dilute gas. Under normal conditions the plasma will be macroscopically neutral (or quasi-neutral), an equal mix of electrons and ions in equilibrium. However, if a strong enough external electric or electromagnetic field is applied, the plasma electrons, which are very light in comparison to the background ions (by a factor of 1836), will separate spatially from the massive ions creating a charge imbalance in the perturbed region. A particle injected into such a plasma would be accelerated by the charge separation field, but since the magnitude of this separation is generally similar to that of the external field, apparently nothing is gained in comparison to a conventional system that simply applies the field directly to the particle. But, the plasma medium acts as the most efficient transformer (currently known) of the transverse field of an electromagnetic wave into longitudinal fields of a plasma wave. In existing accelerator technology various appropriately designed materials are used to convert from transverse propagating extremely intense fields into longitudinal fields that the particles can get a kick from. This process is achieved using two approaches: standing-wave structures (such as resonant cavities) or traveling-wave structures such as disc-loaded waveguides etc. But, the limitation of materials interacting with higher and higher fields is that they eventually get destroyed through ionization and breakdown. Here the plasma accelerator science provides the breakthrough to generate, sustain, and exploit the highest fields ever produced by science in the laboratory.

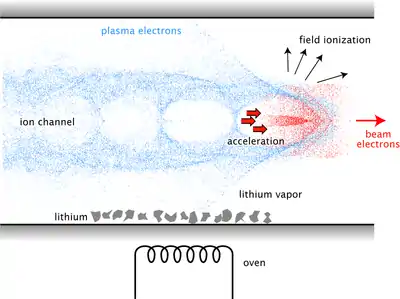

What makes the system useful is the possibility of introducing waves of very high charge separation that propagate through the plasma similar to the traveling-wave concept in the conventional accelerator. The accelerator thereby phase-locks a particle bunch on a wave and this loaded space-charge wave accelerates them to higher velocities while retaining the bunch properties. Currently, plasma wakes are excited by appropriately shaped laser pulses or electron bunches. Plasma electrons are driven out and away from the center of wake by the ponderomotive force or the electrostatic fields from the exciting fields (electron or laser). Plasma ions are too massive to move significantly and are assumed to be stationary at the time-scales of plasma electron response to the exciting fields. As the exciting fields pass through the plasma, the plasma electrons experience a massive attractive force back to the center of the wake by the positive plasma ions chamber, bubble or column that have remained positioned there, as they were originally in the unexcited plasma. This forms a full wake of an extremely high longitudinal (accelerating) and transverse (focusing) electric field. The positive charge from ions in the charge-separation region then creates a huge gradient between the back of the wake, where there are many electrons, and the middle of the wake, where there are mostly ions. Any electrons in between these two areas will be accelerated (in self-injection mechanism). In the external bunch injection schemes the electrons are strategically injected to arrive at the evacuated region during maximum excursion or expulsion of the plasma electrons.

A beam-driven wake can be created by sending a relativistic proton or electron bunch into an appropriate plasma or gas.[18] In some cases, the gas can be ionized by the electron bunch, so that the electron bunch both creates the plasma and the wake. This requires an electron bunch with relatively high charge and thus strong fields. The high fields of the electron bunch then push the plasma electrons out from the center, creating the wake.

Similar to a beam-driven wake, a laser pulse can be used to excite the plasma wake. As the pulse travels through the plasma, the electric field of the light separates the electrons and nucleons in the same way that an external field would.

If the fields are strong enough, all of the ionized plasma electrons can be removed from the center of the wake: this is known as the "blowout regime". Although the particles are not moving very quickly during this period, macroscopically it appears that a "bubble" of charge is moving through the plasma at close to the speed of light. The bubble is the region cleared of electrons that is thus positively charged, followed by the region where the electrons fall back into the center and is thus negatively charged. This leads to a small area of very strong potential gradient following the laser pulse.

In the linear regime, plasma electrons aren't completely removed from the center of the wake. In this case, the linear plasma wave equation can be applied. However, the wake appears very similar to the blowout regime, and the physics of acceleration is the same.

It is this "wakefield" that is used for particle acceleration. A particle injected into the plasma near the high-density area will experience an acceleration toward (or away) from it, an acceleration that continues as the wakefield travels through the column, until the particle eventually reaches the speed of the wakefield. Even higher energies can be reached by injecting the particle to travel across the face of the wakefield, much like a surfer can travel at speeds much higher than the wave they surf on by traveling across it. Accelerators designed to take advantage of this technique have been referred to colloquially as "surfatrons".

Comparison with RF acceleration

The advantage of plasma acceleration is that its acceleration field can be much stronger than that of conventional radio-frequency (RF) accelerators. In RF accelerators, the field has an upper limit determined by the threshold for dielectric breakdown of the acceleration tube. This limits the amount of acceleration over any given area, requiring very long accelerators to reach high energies. In contrast, the maximum field in a plasma is defined by mechanical qualities and turbulence, but is generally several orders of magnitude stronger than with RF accelerators. It is hoped that a compact particle accelerator can be created based on plasma acceleration techniques or accelerators for much higher energy can be built, if long accelerators are realizable with an accelerating field of 10 GV/m.

Plasma acceleration is categorized into several types according to how the electron plasma wave is formed:

- plasma wakefield acceleration (PWFA): The electron plasma wave is formed by an electron or proton bunch.

- laser wakefield acceleration (LWFA): A laser pulse is introduced to form an electron plasma wave.

- laser beat-wave acceleration (LBWA): The electron plasma wave arises based on different frequency generation of two laser pulses. The "Surfatron" is an improvement on this technique.[19]

- self-modulated laser wakefield acceleration (SMLWFA): The formation of an electron plasma wave is achieved by a laser pulse modulated by stimulated Raman forward scattering instability.

The first experimental demonstration of wakefield acceleration, which was performed with PWFA, was reported by a research group at Argonne National Laboratory in 1988.[20]

Formula

The acceleration gradient for a linear plasma wave is:

In this equation, is the electric field, is the speed of light in vacuum, is the mass of the electron, is the plasma electron density (in particles per metre cubed), and is the permittivity of free space.

Experimental laboratories

Currently, plasma-based particle accelerators are in the proof of concept phase at the following institutions:

- Argonne National Laboratory

- INFN Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati[21]

- Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics

- Helmholtz Institute Jena

- Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

- UCLA

- Rutherford Appleton Laboratory

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- United States Naval Research Laboratory

- Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics

- University of Michigan

- Chalk River Laboratories

- Texas Petawatt Laser, University of Texas at Austin

- Advanced Laser-Plasma High-energy Accelerators towards X-rays (ALPHA-X) beam line at the University of Strathclyde

- Scottish Centre for the Application of Plasma-based Accelerators (SCAPA)

- Lund University

- Laboratoire d'Optique Appliquée

- CERN

- DESY / University of Hamburg[22][23]

References

- Tajima, T.; Dawson, J. M. (1979). "Laser Electron Accelerator". Phys. Rev. Lett. 43 (4): 267–270. Bibcode:1979PhRvL..43..267T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.43.267. S2CID 27150340.

- Joshi, C.; Mori, W. B.; Katsouleas, T.; Dawson, J. M.; Kindel, J. M.; Forslund, D. W. (1984). "Ultrahigh gradient particle acceleration by intense laser-driven plasma density waves". Nature. 311 (5986): 525–529. Bibcode:1984Natur.311..525J. doi:10.1038/311525a0.

- Katsouleas, T.; et al. A proposal for a 1 GeV plasma-wakefield acceleration experiment at SLAC. IEEE. doi:10.1109/pac.1997.749806. ISBN 0-7803-4376-X.

- Takeda, S; et al. (November 27, 2014). "Electron Linac Of Test Accelerator Facility For Linear collider" (PDF). Part. Accel. 30: 153–159. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- Leemans, W. P.; et al. (September 24, 2006). "GeV electron beams from a centimetre-scale accelerator". Nature Physics. Springer Nature. 2 (10): 696–699. Bibcode:2006NatPh...2..696L. doi:10.1038/nphys418. ISSN 1745-2473.

- Blumenfeld, Ian; et al. (2007). "Energy doubling of 42 GeV electrons in a metre-scale plasma wakefield accelerator". Nature. Springer Nature. 445 (7129): 741–744. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..741B. doi:10.1038/nature05538. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17301787.

- Wang, Xiaoming; et al. (June 11, 2013). "Quasi-monoenergetic laser-plasma acceleration of electrons to 2 GeV". Nature Communications. Springer Nature. 4 (1): 1988. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4E1988W. doi:10.1038/ncomms2988. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3709475. PMID 23756359.

- Leemans, W. P.; et al. (December 8, 2014). "Multi-GeV Electron Beams from Capillary-Discharge-Guided Subpetawatt Laser Pulses in the Self-Trapping Regime". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 113 (24): 245002. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.113x5002L. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.113.245002. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 25541775.

- Litos, M.; et al. (2014). "High-efficiency acceleration of an electron beam in a plasma wakefield accelerator". Nature. Springer Nature. 515 (7525): 92–95. Bibcode:2014Natur.515...92L. doi:10.1038/nature13882. ISSN 0028-0836. OSTI 1463003. PMID 25373678.

- "Researchers Hit Milestone in Accelerating Particles with Plasma". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. November 5, 2014.

- Assmann, R.; et al. (2014). "Proton-driven plasma wakefield acceleration: a path to the future of high-energy particle physics". Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. 56 (8): 084013. arXiv:1401.4823. Bibcode:2014PPCF...56h4013A. doi:10.1088/0741-3335/56/8/084013. ISSN 1361-6587. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- "AWAKE: Making waves in accelerator technology". Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "World record: Plasma accelerator operates right around the clock". phys.org. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Rekord: Längster Lauf eines Plasmabeschleunigers". scinexx | Das Wissensmagazin (in German). 21 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Important Milestone Reached on the Road to Future Particle Accelerators". AZoM.com. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Plasma accelerators could overcome size limitations of Large Hadron Collider". phys.org. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Maier, Andreas R.; Delbos, Niels M.; Eichner, Timo; Hübner, Lars; Jalas, Sören; Jeppe, Laurids; Jolly, Spencer W.; Kirchen, Manuel; Leroux, Vincent; Messner, Philipp; Schnepp, Matthias; Trunk, Maximilian; Walker, Paul A.; Werle, Christian; Winkler, Paul (18 August 2020). "Decoding Sources of Energy Variability in a Laser-Plasma Accelerator". Physical Review X. 10 (3): 031039. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.10.031039.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Caldwell, A. (2016). "Path to AWAKE: Evolution of the concept". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A. 829: 3–16. arXiv:1511.09032. Bibcode:2016NIMPA.829....3C. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2015.12.050. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002B-2685-0.

- Katsouleas, T.; Dawson, J. M. (1983). "A Plasma Wave Accelerator - Surfatron I". IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 30 (4): 3241–3243. Bibcode:1983ITNS...30.3241K. doi:10.1109/TNS.1983.4336628.

- Rosenzweig, J. B.; et al. (July 4, 1988). "Experimental Observation of Plasma Wake-Field Acceleration". Physical Review Letters. American Physical Society (APS). 61 (1): 98–101. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..61...98R. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.61.98. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10038703.

- "SPARC_LAB (Sources for Plasma Accelerators and Radiation Compton with Laser And Beam) facility at LNF".

- "DESY News: Innovative accelerator project produces first particle beam". Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- "Laser-Plasma Driven Light Sources". LUX. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- Joshi, C. (2006). "Plasma Accelerators". Scientific American. 294 (2): 40–47. Bibcode:2006SciAm.294b..40J. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0206-40. PMID 16478025.

- Katsouleas, T (2004). "Accelerator physics: Electrons hang ten on laser wake". Nature. 431 (7008): 515–516. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..515K. doi:10.1038/431515a. PMID 15457239.

- Joshi, C.; Katsouleas, T. (2003). "Plasma accelerators at the energy frontier and on tabletops". Physics Today. 56 (6): 47–51. Bibcode:2003PhT....56f..47J. doi:10.1063/1.1595054.

- Joshi, C. & Malka, V. (2010). "Focus on Laser- and Beam-Driven Plasma Accelerators". New Journal of Physics. 12 (4): 045003. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/12/4/045003.