Plasmodesma

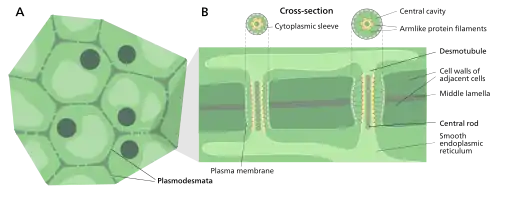

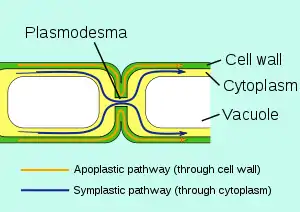

Plasmodesmata (singular: plasmodesma) are microscopic channels which traverse the cell walls of plant cells[2] and some algal cells, enabling transport and communication between them. Plasmodesmata evolved independently in several lineages,[3] and species that have these structures include members of the Charophyceae, Charales, Coleochaetales and Phaeophyceae (which are all algae), as well as all embryophytes, better known as land plants.[4] Unlike animal cells, almost every plant cell is surrounded by a polysaccharide cell wall. Neighbouring plant cells are therefore separated by a pair of cell walls and the intervening middle lamella, forming an extracellular domain known as the apoplast. Although cell walls are permeable to small soluble proteins and other solutes, plasmodesmata enable direct, regulated, symplastic transport of substances between cells. There are two forms of plasmodesmata: primary plasmodesmata, which are formed during cell division, and secondary plasmodesmata, which can form between mature cells.[5]

Similar structures, called gap junctions[6] and membrane nanotubes, interconnect animal cells[7] and stromules form between plastids in plant cells.[8]

Formation

Primary plasmodesmata are formed when fractions of the endoplasmic reticulum are trapped across the middle lamella as new cell wall are synthesized between two newly divided plant cells. These eventually become the cytoplasmic connections between cells. At the formation site, the wall is not thickened further, and depressions or thin areas known as pits are formed in the walls. Pits normally pair up between adjacent cells. Plasmodesmata can also be inserted into existing cell walls between non-dividing cells (secondary plasmodesmata).[9]

Primary plasmodesmata

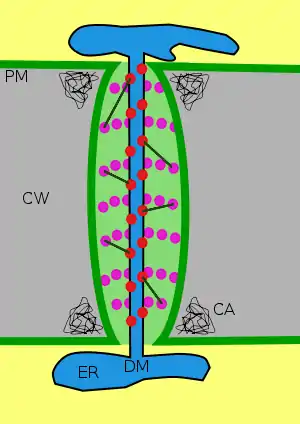

The formation of primary plasmodesmata occurs during the part of the cellular division process where the endoplasmic reticulum and the new plate are fused together, this process results in the formation of a cytoplasmic pore (or cytoplasmic sleeve). The desmotubule, also known as the appressed ER, forms alongside the cortical ER. Both the appressed ER and the cortical ER are packed tightly together, thus leaving no room for any luminal space. It is proposed that the appressed ER acts as a membrane transportation route in the plasmodesmata. When filaments of the cortical ER are entangled in the formation of a new cell plate, plasmodesmata formation occurs in land plants. It is hypothesized that the appressed ER forms due to a combination of pressure from a growing cell wall and interaction from ER and PM proteins. Primary plasmodesmata are often present in areas where the cell walls appear to be thinner. This is due to the fact that as a cell wall expands, the abundance of the primary plasmodesmata decreases. In order to further expand plasmodesmal density during cell wall growth secondary plasmodesmata are produced. The process of secondary plasmodesmata formation is still to be fully understood, however various degrading enzymes and ER proteins are said to stimulate the process.[10]

Structure

Plasmodesmatal plasma membrane

A typical plant cell may have between 103 and 105 plasmodesmata connecting it with adjacent cells[11] equating to between 1 and 10 per µm2.[12] Plasmodesmata are approximately 50–60 nm in diameter at the midpoint and are constructed of three main layers, the plasma membrane, the cytoplasmic sleeve, and the desmotubule.[11] They can transverse cell walls that are up to 90 nm thick.[12]

The plasma membrane portion of the plasmodesma is a continuous extension of the cell membrane or plasmalemma and has a similar phospholipid bilayer structure.[13]

The cytoplasmic sleeve is a fluid-filled space enclosed by the plasmalemma and is a continuous extension of the cytosol. Trafficking of molecules and ions through plasmodesmata occurs through this space. Smaller molecules (e.g. sugars and amino acids) and ions can easily pass through plasmodesmata by diffusion without the need for additional chemical energy. Larger molecules, including proteins (for example green fluorescent protein) and RNA, can also pass through the cytoplasmic sleeve diffusively.[14] Plasmodesmatal transport of some larger molecules is facilitated by mechanisms that are currently unknown. One mechanism of regulation of the permeability of plasmodesmata is the accumulation of the polysaccharide callose around the neck region to form a collar, thereby reducing the diameter of the pore available for transport of substances.[13] Through dilation, active gating or structural remodeling the permeability of the plasmodesmata is increased. This increase in plasmodesmata pore permeability allows for larger molecules, or macromolecules, such as signaling molecules, transcription factors and RNA-protein complexes to be transported to various cellular compartments.[10]

Desmotubule

The desmotubule is a tube of appressed (flattened) endoplasmic reticulum that runs between two adjacent cells.[15] Some molecules are known to be transported through this channel,[16] but it is not thought to be the main route for plasmodesmatal transport.

Around the desmotubule and the plasma membrane areas of an electron dense material have been seen, often joined together by spoke-like structures that seem to split the plasmodesma into smaller channels.[15] These structures may be composed of myosin[17][18][19] and actin,[18][20] which are part of the cell's cytoskeleton. If this is the case these proteins could be used in the selective transport of large molecules between the two cells.

Transport

Plasmodesmata have been shown to transport proteins (including transcription factors), short interfering RNA, messenger RNA, viroids, and viral genomes from cell to cell. One example of a viral movement proteins is the tobacco mosaic virus MP-30. MP-30 is thought to bind to the virus's own genome and shuttle it from infected cells to uninfected cells through plasmodesmata.[14] Flowering Locus T protein moves from leaves to the shoot apical meristem through plasmodesmata to initiate flowering.[21]

Plasmodesmata are also used by cells in phloem, and symplastic transport is used to regulate the sieve-tube cells by the companion cells.[22]

The size of molecules that can pass through plasmodesmata is determined by the size exclusion limit. This limit is highly variable and is subject to active modification.[5] For example, MP-30 is able to increase the size exclusion limit from 700 Daltons to 9400 Daltons thereby aiding its movement through a plant.[23] Also, increasing calcium concentrations in the cytoplasm, either by injection or by cold-induction, has been shown to constrict the opening of surrounding plasmodesmata and limit transport.[24]

Several models for possible active transport through plasmodesmata exist. It has been suggested that such transport is mediated by interactions with proteins localized on the desmotubule, and/or by chaperones partially unfolding proteins, allowing them to fit through the narrow passage. A similar mechanism may be involved in transporting viral nucleic acids through the plasmodesmata.[25]

Cytoskeletal components of Plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata link almost every cell within a plant, which can cause negative effects such as the spread of viruses. In order to understand this we must first look at cytoskeletal components, such as actin microfilaments, microtubules, and myosin proteins, and how they are related to cell to cell transport. Actin microfilaments are linked to the transport of viral movement proteins to plasmodesmata which allow for cell to cell transport through the plasmodesmata. Fluorescent tagging for co-expression in tobacco leaves showed that actin filaments are responsible for transporting viral movement proteins to the plasmodesmata. When actin polymerization was blocked it caused a decrease in plasmodesmata targeting of the movement proteins in the tobacco and allowed for 10-kDa (rather than 126-kDa) components to move between tobacco mesophyll cells. This also impacted cell to cell movement of molecules within the tobacco plant.[26]

Viruses

Viruses break down actin filaments within the plasmodesmata channel in order to move within the plant. For example, when the cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) gets into plants it is able to travel through almost every cell through utilization of viral movement proteins to transport themselves through the plasmodesmata. When tobacco leaves are treated with a drug that stabilizes actin filaments, phalloidin, the cucumber mosaic virus movement proteins are unable to increase the plasmodesmata size exclusion limit (SEL).[26]

Myosin

High amounts of myosin proteins are found at the sites of plasmodesmata. These proteins are involved in directing viral cargoes to plasmodesmata. When mutant forms of myosin were tested in tobacco plants, viral protein targeting to plasmodesmata was negatively affected. Permanent binding of myosin to actin, which was induced by a drug, caused a decrease in cell to cell movement. Viruses are also able to selectively bind to myosin proteins.[26]

Microtubules

Microtubules are also are also an important role in cell to cell transport of viral RNA. Viruses use many different methods of transporting themselves from cell to cell, and one of those methods associating the N-terminal domain of its RNA to localize to plasmodesmata through microtubules. Tobacco plants injected with tobacco movement viruses that were kept in high temperatures there was a strong correlation between TMV movement proteins that were attached to GFP with microtubules. This led to an increase in the spread of viral RNA through the tobacco.[26]

Plasmodesmata and Callose

Plasmodesmata regulation and structure are regulated by a beta 1,3-glucan polymer known as callose. Callose is found in cell plates during the process of cytokinesis, as this process reaches completion the levels of calls decrease. The only callose rich parts of the cell include the sections of the cell wall that plasmodesmata are present. In order to regulate what is transported in the plasmodesmata, callose must be present. Callose provides the mechanism in which plasmodesmata permeability is regulated. In order to control what is transported between different tissues, the plasmodesmata undergo several specialized conformational changes.[10]

The activity of plasmodesmata are linked to physiological and developmental processes within plants. There is a hormone signaling pathway that relays primary cellular signals to the plasmodesmata. There are also patterns of environmental, physiological, and developmental cues that show relation to plasmodesmata function. An important mechanism of plasmodesmata is the ability to gate its channels. Callose levels have been proved to be a method of changing plasmodesmata aperture size.[27] Callose deposits are found at the neck of the plasmodesmata in new cell walls that have been formed. The level of deposits at the plasmodesmata can fluctuate which shows that there are signals that trigger an accumulation of callose at the plasmodesmata and cause plasmodesmata to become gated or more open. Enzyme activities of Beta 1,3-glucan synthase and hydrolases are involved in changes in plasmodesmata cellulose level. Some extracellular signals change transcription of activities of this synthase and hydrolase. Arabidopsis thailana contain callose synthase genes that encode a catalytic subunit of B-1,3-glucan. Gain of function mutants in this gene pool show increased deposition of callose at plasmodesmata and a decrease in macromolecular trafficking as well as a defective root system during development.[26]

See also

References

- Maule, Andrew (December 2008). "Plasmodesmata: structure, function and biogenesis". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 11 (6): 680–686. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2008.08.002. PMID 18824402.

- Oparka, K. J. (2005). Plasmodesmata. Blackwell Pub Professional. ISBN 978-1-4051-2554-3.

- Zoë A. Popper; Gurvan Michel; Cécile Hervé; David S. Domozych; William G.T. Willats; Maria G. Tuohy; Bernard Kloareg; Dagmar B. Stengel (2011). "Evolution and Diversity of Plant Cell Walls: From Algae to Flowering Plants" (PDF). Annual Review of Plant Biology. 62: 567–590. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. hdl:10379/6762. PMID 21351878.

- Graham, LE; Cook, ME; Busse, JS (2000), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97, 4535-4540.

- Jan Traas; Teva Vernoux (29 June 2002). "The shoot apical meristem: the dynamics of a stable structure". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 357 (1422): 737–747. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1091. PMC 1692983. PMID 12079669.

- Bruce Alberts (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Gallagher KL, Benfey PN (15 January 2005). "Not just another hole in the wall: understanding intercellular protein trafficking". Genes & Development. 19 (2): 189–95. doi:10.1101/gad.1271005. PMID 15655108.

- Gray JC, Sullivan JA, Hibberd JM, Hansen MR (2001). "Stromules: mobile protrusions and interconnections between plastids". Plant Biology. 3 (3): 223–33. doi:10.1055/s-2001-15204.

- Lucas, W.; Ding, B.; Van der Schoot, C. (1993). "Tansley Review No.58 Plasmodesmata and the supracellular nature of plants". New Phytologist. 125 (3): 435–476. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03897.x. JSTOR 2558257.

- Sager, Ross (June 7, 2018). "Plasmodesmata at a Glance". Journal of Cell Science. 131 (11): jcs209346. doi:10.1242/jcs.209346. PMID 29880547.

- Robards, AW (1975). "Plasmodesmata". Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 26: 13–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.26.060175.000305.

- Lodish, Berk, Zipursky, Matsudaira, Baltimore, Darnell (2000). "22". Molecular Cell Biology (4 ed.). pp. 998. ISBN 978-0-7167-3706-3. OCLC 41266312.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- AW Robards (1976). "Plasmodesmata in higher plants". In BES Gunning; AW Robards (eds.). Intercellular communications in plants: studies on plasmodesmata. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 15–57.

- A. G. Roberts; K. J. Oparka (1 January 2003). "Plasmodesmata and the control of symplastic transport". Plant, Cell & Environment. 26 (1): 103–124. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00950.x.

- Overall, RL; Wolfe, J; Gunning, BES (1982). "Intercellular communication in Azolla roots: I. Ultrastructure of plasmodesmata". Protoplasma. 111 (2): 134–150. doi:10.1007/bf01282071. S2CID 5970113.

- Cantrill, LC; Overall, RL; Goodwin, PB (1999). "Cell-to-cell communication via plant endomembranes". Cell Biology International. 23 (10): 653–661. doi:10.1006/cbir.1999.0431. PMID 10736188. S2CID 23026878.

- Radford, JE; White, RG (1998). "Localization of a myosin‐like protein to plasmodesmata". Plant Journal. 14 (6): 743–750. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00162.x. PMID 9681037.

- Blackman, LM; Overall, RL (1998). "Immunolocalisation of the cytoskeleton to plasmodesmata of Chara corallina". Plant Journal. 14 (6): 733–741. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00161.x.

- Reichelt, S; Knight, AE; Hodge, TP; Baluska, F; Samaj, J; Volkmann, D; Kendrick-Jones, J (1999). "Characterization of the unconventional myosin VIII in plant cells and its localization at the post-cytokinetic cell wall". Plant Journal. 19 (5): 555–569. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00553.x. PMID 10504577.

- White, RG; Badelt, K; Overall, RL; Vesk, M (1994). "Actin associated with plasmodesmata". Protoplasma. 180 (3–4): 169–184. doi:10.1007/bf01507853. S2CID 9767392.

- Corbesier, L., Vincent, C., Jang, S., Fornara, F., Fan, Q.; et al. (2007). "FT protein movement contributes to long distance signalling in floral induction of Arabidopsis". Science. 316 (5827): 1030–1033. Bibcode:2007Sci...316.1030C. doi:10.1126/science.1141752. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-3874-C. PMID 17446353. S2CID 34132579.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Phloem

- Shmuel, Wolf; William, J. Lucas; Carl, M. Deom (1989). "Movement Protein of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Modifies Plasmodesmatal Size Exclusion Limit". Science. 246 (4928): 377–379. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..377W. doi:10.1126/science.246.4928.377. PMID 16552920. S2CID 2403087.

- Aaziz, R.; Dinant, S.; Epel, B. L. (1 July 2001). "Plasmodesmata and plant cytoskeleton". Trends in Plant Science. 6 (7): 326–330. doi:10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01981-1. ISSN 1360-1385. PMID 11435172.

- Plant Physiology lectures, chapter 5 Archived 2010-02-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Sager, Ross (September 26, 2014). "Plasmodesmata in integrated cell signalling: insights from development and environmental signals and stresses". Journal of Experimental Botany. 65 (22): 6337–58. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru365. PMC 4303807. PMID 25262225.

- Storme, Nico (April 21, 2014). "Callose homeostasis at plasmodesmata: molecular regulators and developmental relevance". Frontiers in Plant Science. 5: 138. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00138. PMC 4001042. PMID 24795733.