Pneumatosis

Pneumatosis, also known as emphysema, is the abnormal presence of air or other gas within tissues.

| Pneumatosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Emphysema |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Left lung completely affected by bullae shown in contrast to a normal lung on the right. | |

| Causes | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

In the lungs, emphysema involves enlargement of the distal airspaces,[1] and is a major feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

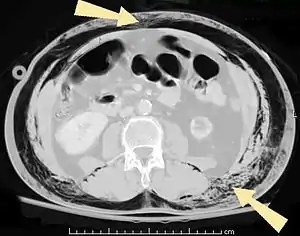

Pneumoperitoneum (or peritoneal emphysema) is air or gas in the abdominal cavity, and is most commonly caused by a perforated abdominal organ. Pneumatosis is also a frequent result of surgery.

Pneumarthrosis, the presence of air in a joint, is rarely a serious sign.

By location

Lungs

.jpg.webp)

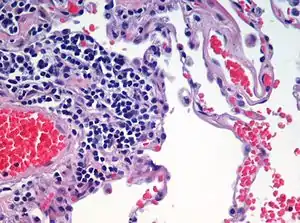

Pulmonary emphysema, more usually called emphysema, is characterised by air-filled cavities or spaces, (pneumatoses) in the lung, that can vary in size and may be very large. The spaces are caused by the breakdown of the walls of the alveoli and they replace the spongy lung parenchyma. This reduces the total alveolar surface available for gas exchange leading to a reduction in oxygen supply for the blood.[2] Emphysema usually affects the middle aged or older population. This is because the disease takes time to develop with the effects of smoking, and other risk factors. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a genetic risk factor that may lead to the condition presenting earlier.[3]

It is a typical feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a type of obstructive lung disease characterized by long-term breathing problems and poor airflow.[4][5] Even without COPD, the finding of pulmonary emphysema on a CT lung scan confers a higher mortality in tobacco smokers.[6] In 2016 in the United States there were 6,977 deaths from emphysema – 2.2 per 100,000 of the population.[7] A study on the effects of tobacco and cannabis smoking showed that a possibly cumulative toxic effect could be a risk factor for developing emphysema, and spontaneous pneumothorax.[8] There is an association between emphysema and osteoporosis.[9]

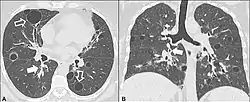

There are three subtypes of pulmonary emphysema – centrilobular or centriacinar, panlobular or panacinar, and paraseptal or distal acinar emphysema, related to the anatomy of the lobules of the lung.[10][11] These are not associated with fibrosis (scarring). A fourth type known as irregular emphysema involves the acinus irregularly and is associated with fibrosis.[11] Though the subtypes can be seen on imaging they are not well-defined clinically.[12]

Only the first two types of emphysema – centrilobular, and panlobular are associated with significant airflow obstruction, with that of centrilobular emphysema around 20 times more common than panlobular.[11]

Centrilobular emphysema

Centrilobular emphysema also called centriacinar emphysema, affects the centrilobular portion of the lung, the area around the terminal bronchiole, and the first respiratory bronchiole, and can be seen on imaging as an area around the tip of the visible pulmonary artery. Centrilobular emphysema is the most common type usually associated with smoking, and with chronic bronchitis.[11] The disease progresses from the centrilobular portion, leaving the lung parenchyma in the surrounding (perilobular) region preserved.[10] Usually the upper lobes of the lungs are affected.[11]

Panlobular emphysema

Panlobular emphysema also called panacinar emphysema can involve the whole lung or mainly the lower lobes.[13] This type of emphysema is associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (A1AD or AATD),[13] and is not related to smoking.[12]

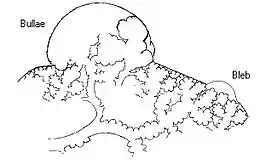

Paraseptal emphysema

Paraseptal emphysema also called distal acinar emphysema relates to emphysematous change next to a pleural surface, or to a fissure.[12][14] The cystic spaces known as blebs or bullae that form in paraseptal emphysema typically occur in just one layer beneath the pleura. This distinguishes it from the honeycombing of small cystic spaces seen in fibrosis that typically occurs in layers.[14] This type of emphysema is not associated with airflow obstruction.[15]

Bullous emphysema

When the subpleural bullae are significant the emphysema is called bullous emphysema. Bullae can become extensive and combine to form giant bullae. These can be large enough to take up a third of a hemithorax, compress the lung parenchyma, and cause displacement. The emphysema is now termed giant bullous emphysema, more commonly called vanishing lung syndrome due to the compressed parenchyma.[16] A bleb or bulla may sometimes rupture and cause a pneumothorax.[11]

HIV associated emphysema

Classic lung diseases are a complication of HIV/AIDS with emphysema being a source of disease. HIV is cited as a risk factor for the development of emphysema regardless of smoking status. HIV associated emphysema occurs over a much shorter time than that associated with smoking. It is thought that an understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the triggering of HIV associated emphysema may help in the understanding of the mechanisms of the development of smoking-related emphysema.[17]

Ritalin lung

The intravenous use of methylphenidate, commonly marketed as Ritalin can lead to emphysematous changes known as Ritalin lung. The mechanism underlying this link is not clearly understood. Ritalin tablets contain talc as a filler, and these need to be crushed and dissolved for injecting. It has been suggested that the talc exposure causes granulomatosis leading to alveolar destruction. However, other intravenous drugs also contain talc and there is no associated emphysematous change. HRCT shows panlobular emphysema.[18]

CPFE

Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is a rare syndrome that shows upper-lobe emphysema, together with lower-lobe interstitial fibrosis. This is diagnosed by CT scan.[19] This syndrome presents a marked susceptibility for the development of pulmonary hypertension.[20]

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is a collection of air outside of the normal air space of the pulmonary alveoli, found instead inside the connective tissue of the peribronchovascular sheaths, interlobular septa, and visceral pleura.

Congenital lobar emphysema

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE), also known as congenital lobar overinflation and infantile lobar emphysema,[21] is a neonatal condition associated with enlarged air spaces in the lungs of newborn infants. It is diagnosed around the time of birth or in the first 6 months of life, occurring more often in boys than girls. CLE affects the upper lung lobes more than the lower lobes, and the left lung more often than the right lung.[22] CLE is defined as the hyperinflation of one or more lobes of the lung due to the partial obstruction of the bronchus. This causes symptoms of pressure on the nearby organs. It is associated with several cardiac abnormalities such as patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, and tetralogy of Fallot.[23] Although CLE may be caused by the abnormal development of bronchi, or compression of airways by nearby tissues, no cause is identified in half of cases.[22] CT scan of the lungs is useful in assessing the anatomy of the lung lobes and status of the neighbouring lobes on whether they are hypoplastic or not. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful in assessing vascular abnormalities and mediastinal masses.[23]

Compensatory emphysema

Compensatory emphysema, is overinflation of part of a lung in response to either removal by surgery of another part of the lung or deceased size of another part of the lung.[24]

Parenchymal focalities

A focal lung pneumatosis, is a solitary volume of air in the lung that is larger than alveoli. A focal lung pneumatosis can be classified by its wall thickness:

- A pulmonary bleb or bulla has a wall thickness of less than 1 mm[25] Blebs and bullae are also known as a focal regions of emphysema.[26]

- A pulmonary cyst has a wall thickness of up to 4 mm.[25] A minimum wall thickness of 1 mm has been suggested,[25] but thin-walled pockets may be included in the definition as well.[27] Pulmonary cysts are not associated with either smoking or emphysema.[28]

- A cavity has a wall thickness of more than 4 mm[25]

The terms above, when referring to sites other than the lungs, often imply fluid content.

Other thoracic

- Pneumothorax, air or gas in the pleural space

- Pneumomediastinum, air or gas in the mediastinum

- Also called mediastinal emphysema or pneumatosis/emphysema of the mediastinum

Abdominal

- Pneumoperitoneum (or peritoneal emphysema), air or gas in the abdominal cavity. The most common cause is a perforated abdominal viscus, generally a perforated peptic ulcer, although any part of the bowel may perforate from a benign ulcer, tumor or abdominal trauma.

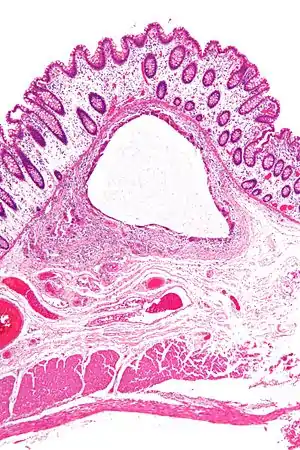

- Pneumatosis intestinalis, air or gas cysts in the bowel wall

- Gastric pneumatosis (or gastric emphysema) is air or gas cysts in the stomach wall[29]

Joints

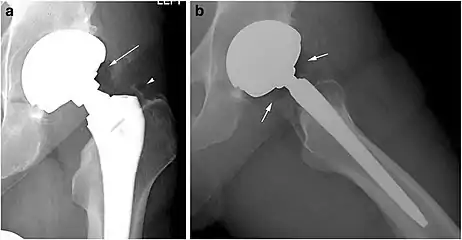

Pneumarthrosis is the presence of air in a joint. Its presentation on radiography is a radiolucent cleft often called a vacuum phenomenon, or vacuum sign.[30] Pneumarthrosis is associated with osteoarthritis and spondylosis.[31]

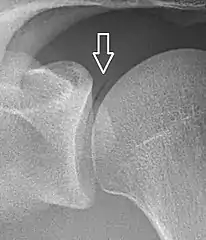

Pneumarthrosis is a common normal finding in shoulders[30] as well as in sternoclavicular joints.[32] It is believed to be a cause of the sounds of joint cracking.[31] It is also a common normal post-operative finding at least after spinal surgery.[33] Pneumarthrosis is extremely rare in conjunction with fluid or pus in a joint, and its presence can therefore practically exclude infection.[31]

X-ray of a hip with hip replacement and pneumarthrosis, in this case aseptic.

X-ray of a hip with hip replacement and pneumarthrosis, in this case aseptic. A vacuum sign, or vacuum phenomenon, is a normal finding on shoulder X-rays.

A vacuum sign, or vacuum phenomenon, is a normal finding on shoulder X-rays.

Other

Subcutaneous emphysema is found in the deepest layer of the skin. Emphysematous cystitis is a condition of gas in the bladder wall. On occasion this may give rise to secondary subcutaneous emphysema which has a poor prognosis.[34]

Pneumoparotitis is the presence of air in the parotid gland caused by raised air pressure in the mouth often as a result of playing wind instruments. In rare cases air may escape from the gland and give rise to subcutaneous emphysema in the face, neck, or mediastinum.[35][36]

References

- page 64 in: Adrian Shifren (2006). The Washington Manual Pulmonary Medicine Subspecialty Consult, Washington manual subspecialty consult series. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781743761.

- Saladin, K (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 650. ISBN 9780071222075.

- Murphy, Andrew; Danaher, Luke. "Pulmonary emphysema". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Algusti, Alvar G.; et al. (2017). "Definition and Overview". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). pp. 6–17.

- Roversi, Sara; Corbetta, Lorenzo; Clini, Enrico (5 May 2017). "GOLD 2017 recommendations for COPD patients: toward a more personalized approach" (PDF). COPD Research and Practice. 3. doi:10.1186/s40749-017-0024-y.

- Diedtra Henderson (2014-12-16). "Emphysema on CT Without COPD Predicts Higher Mortality Risk". Medscape.

- "FastStats". www.cdc.gov. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Underner, M; Urban, T; Perriot, J; et al. (December 2018). "[Spontaneous pneumothorax and lung emphysema in cannabis users]". Revue de pneumologie clinique. 74 (6): 400–415. doi:10.1016/j.pneumo.2018.06.003. PMID 30420278.

- "COPD and comorbidities" (PDF). p. 133. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Takahashi, M; Fukuoka, J (2008). "Imaging of pulmonary emphysema: a pictorial review". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 3 (2): 193–204. doi:10.2147/COPD.S2639. PMC 2629965. PMID 18686729.

- Kumar, V (2018). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. pp. 498–501. ISBN 9780323353175.

- Smith, B (January 2014). "Pulmonary emphysema subtypes on computed tomography: the MESA COPD study". Am J Med. 127 (1): 94.e7–23. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.020. PMC 3882898. PMID 24384106.

- Weerakkody, Yuranga. "Panlobular emphysema | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "Chest". Radiology assistant. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Mosenifar, Zab (April 2019). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)". emedicine.medscape. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Sharma, N; Justaniah, AM (August 2009). "Vanishing lung syndrome (giant bullous emphysema):CT findings in 7 patients and a literature review". J Thoracic Imaging. 24 (3): 227–230. doi:10.1097/RTI.0b013e31819b9f2a. PMID 19704328.

- Petrache, I (May 2008). "HIV associated pulmonary emphysema: a review of the literature and inquiry into its mechanism". Thorax. 63 (5): 463–9. doi:10.1136/thx.2007.079111. PMID 18443163.

- Sharma, R. "Ritalin lung". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Wand, O; Kramer, MR (January 2018). "The Syndrome of Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema - CPFE". Harefuah. 157 (1): 28–33. PMID 29374870.

- Seeger, W (December 2013). "Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung diseases". J Am Coll Cardiol. 62 (25 Suppl): 109–116. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.036. PMID 24355635.

- "UpToDate: Congenital lobar emphysema". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Guidry, Christopher; McGahren, Eugene D. (June 2012). "Pediatric Chest I". Surgical Clinics of North America. 92 (3): 615–643. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2012.03.013. PMID 22595712.

- Demir, Omer (May 2019). "Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnosis and treatment options". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 14: 921–928. doi:10.2147/COPD.S170581. PMC 6507121. PMID 31118601.

- Han, Xinwei; Wang, Chen (2018). Airway Stenting in Interventional Radiology. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 9789811316197.

- Dr Daniel J Bell and Dr Yuranga Weerakkody. "Pulmonary cyst". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Gaillard, Frank. "Pulmonary bullae | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Araki, Tetsuro; Nishino, Mizuki; Gao, Wei; Dupuis, Josée; Putman, Rachel K; Washko, George R; Hunninghake, Gary M; O'Connor, George T; Hatabu, Hiroto (2015). "Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT: are they part of aging change or of clinical significance?". Thorax. 70 (12): 1156–1162. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207653. ISSN 0040-6376. PMC 4848007. PMID 26514407.

- Araki, Tetsuo. "Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT:are they part of ageing change or of clinical significance" (PDF). Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Gastric emphysema | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Abhijit Datir; et al. "Vacuum phenomenon in shoulder". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- Page 60 in: Harry Griffiths (2008). Musculoskeletal Radiology. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420020663.

- Restrepo, Carlos S.; Martinez, Santiago; Lemos, Diego F.; Washington, Lacey; McAdams, H. Page; Vargas, Daniel; Lemos, Julio A.; Carrillo, Jorge A.; Diethelm, Lisa (2009). "Imaging Appearances of the Sternum and Sternoclavicular Joints". RadioGraphics. 29 (3): 839–859. doi:10.1148/rg.293055136. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 19448119.

- Mall, J C; Kaiser, J A (1987). "The usual appearance of the postoperative lumbar spine". RadioGraphics. 7 (2): 245–269. doi:10.1148/radiographics.7.2.3448634. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 3448634.

- Sadek AR, Blake H, Mehta A (June 2011). "Emphysematous cystitis with clinical subcutaneous emphysema". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 4 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1865-1380-4-26. PMC 3123544. PMID 21668949.

- McCormick, Michael E.; Bawa, Gurneet; Shah, Rahul K. (2013). "Idiopathic recurrent pneumoparotitis". American Journal of Otolaryngology. 34 (2): 180–182. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.11.005. ISSN 0196-0709. PMID 23318047.

- Joiner MC; van der Kogel A (15 June 2016). Basic Clinical Radiobiology, Fifth Edition. CRC Press. p. 1908. ISBN 978-0-340-80893-1.