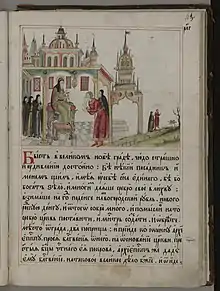

Posadnik

Posadnik (Cyrillic: посадник, (literally: по-садник - pre-sident) was the mayor in some East Slavic cities or towns. Most notably, the posadnik (equivalent to a stadtholder, burgomeister, or podestà in the medieval west) was the mayor of Novgorod and Pskov. The term comes from the Old Church Slavic "posaditi," meaning to put or place; they were so-called because the prince in Kiev originally placed them in the city to rule on his behalf. Beginning in the 12th century, they were elected locally.

Novgorod

Despite legends of posadniks such as Gostomysl that were set in the 9th century, the term posadnik first appeared in the Primary Chronicle under the year 997. The earliest Novgorodian posadniks include Dobrynya (an uncle of Vladimir the Great), his son Konstantin Dobrynich and Ostromir, who is famous for patronizing the Ostromir Gospels, among the first books published in Russia (it is now housed in the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg). Also mention in a document from year 1189 referenced in SDHK 44456.

In the Novgorod Republic, the city posadnik was elected from among the boyars by the veche (public assembly). The elections were held annually. Novgorod boyars differed from boyars in other Rus' lands in that the category was not caste-like and that every rich merchant could reasonably hope to reach the rank of boyar. Valentin Yanin, the Soviet "dean" of medieval Novgorodian history, has found that most posadniks held the office consecutively for sometimes a decade or more and then often passed the office on to their sons or another close relative, indicating that the office was held within boyar clans and that the elections were not really "free and fair."[1] Yanin's theory challenged historians' understanding of the Novgorod Republic, showing it to be a boyar republic with little or no democratic elements. It also showed the land-owning boyarstvo to be more powerful than the merchant and artisan classes, which until that time were thought to play a significant role in the political life of the city. It also called into question the true nature of the veche, which up until that time had been considered democratic by most scholars. Yanin's interpretation of the Novgorod government as an hereditary oligarchy is not universally accepted, however.

Originally there was one posadnik, but gradually over time the office multiplied until, by the end of the Republic, there were something like 24 posadniks. There were also posadniks for each of the city's boroughs (called ends - "kontsy", singular "konets" in Russian). The multiplication of the office dates to the 1350s, when Posadnik Ontsifor Lukinich implemented a series of reforms.[2] Retired posadniks took the title "old posadnik", or старый посадник) and the current, serving posadnik was known as the "stepennyi" posadnik (степенный посадник). In accordance with the reform of 1416-1417, the number of posadniks was increased threefold and stepennyi posadniks were to be elected for a six-month period. In this manner, the various boyar clans could share power and one or another of them would neither monopolize power or be left out if they lost an election. It, however, diluted power in the boyarstvo. Some scholars have argued that the Archbishop of Novgorod became the head of the Republic and stood above the fray of partisan politics that raged among the boyardom, but the archbishops seem to have shared power with the boyardom and the collective leadership tried to rule by consensus. [3] The dilution of boyar power may, however, have weakened Novgorod in the 15th century, thus explaining the series of defeats it suffered at Moscow's hands and the eventual fall of independent Novgorod.

The posadnikdom (mayoralty) was abolished along with the veche when Grand Prince Ivan III of Moscow took the city in 1478. In fact, upon being asked by Archbishop Feofil (1470-1480) on behalf of the Novgorodians what type of government he wanted, Ivan (speaking through Prince Patrikeev) told them "there will be no veche bell in our patrimony of Novgorod; there will be no posadnik, and we will conduct our own government."[4]

Pskov

There were 78 known posadniks in Pskov between 1308 and 1510.[5] The posadnichestvo was abolished in Pskov in 1510 when Grand Prince Vasily III took direct control of the city.

References

- Valentin Lavrent'evich Yanin, Novgorodskie Posadniki (Moscow: Moscow State University, 1962; reprinted Moscow: Iazyki Russkoi kultury, 2003).

- Yanin, Novgorodskie Posadniki, 262-287.

- Michael C. Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest," Kritika 8, No. 2 (Spr. 2007): 231-270.

- Moskovskii Letopisnii svod, Vol. 25 in Polnoe Sobranie Russkikh Letopisei(Moscow ANSSSR, 1949, p. 146 (emphasis added). See also Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest," 267.

- For a discussion of the office in Pskov, see Lawrence Langer, “The Posadnichestvo of Pskov: Some Aspects of Urban Administration in Medieval Russia.” Slavic Review 43, no. 1 (1984): 46−62.