Principality of Orange

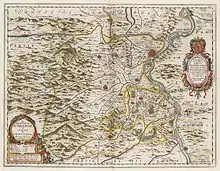

The Principality of Orange (French: la Principauté d'Orange) was, from 1163 to 1713, a feudal state in Provence, in the south of modern-day France, on the east bank of the river Rhone, north of the city of Avignon, and surrounded by the independent papal state of Comtat Venaissin.

Principality of Orange Principauté d'Orange | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1163–1713 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

.png.webp) Map of the Principality of Orange (with south at the top) | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal state of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Orange | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||||||

| Prince of Orange | |||||||||

• 1171–1185 | Bertrand I of Baux (first) | ||||||||

• 1650–1702 | William III of Orange and England (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Principality status granted | 1163 | ||||||||

• Ceded to France by the Treaty of Utrecht | 1713 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 108 sq mi (280 km2) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

It was constituted in 1163, when Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I elevated the Burgundian County of Orange (consisting of the city of Orange and the land surrounding it) to a sovereign principality within the Empire. The principality became part of the scattered holdings of the house of Orange-Nassau from the time that William the Silent inherited the title of Prince of Orange from his cousin in 1544, until it was finally ceded to France in 1713 under the Treaty of Utrecht. Although permanently lost by the Nassaus then, this fief gave its name to the extant Royal House of the Netherlands. The area of the principality was approximately 12 miles (19 km) long by 9 miles (14 km) wide, or 108 square miles (280 km2).[1]

History

The Carolingian counts of Orange had their origin in the 8th century, and the fief passed into the family of the lords of Baux. The Baux counts of Orange became fully independent with the breakup of the Kingdom of Arles after 1033. In 1163 Orange was raised to a principality, as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1365, Orange university was founded by Charles IV when he was in Arles for his coronation as king of Arles.

In 1431 the Count of Provence waived taxation duties for Orange's rulers (Mary of Baux-Orange and Jean de Châlons of Burgundy) in exchange for liquid assets to be used for a ransom. The town and principality of Orange was a part of administration and province of Dauphiné.

In 1544, William the Silent, count of Nassau, with large properties in the Netherlands, inherited the principality. William, 11 years old at the time, was the cousin of René of Châlon who died without an heir when he was shot at St. Dizier in 1544 during the Franco-Imperial wars. René, it turned out, willed his entire fortune to this very young relative. Among those titles and estates was the Principality of Orange. René's mother, Claudia, had held the title prior to it being passed to young William since Philibert de Châlon was her brother.

When William inherited the Principality, it was incorporated into the holdings of what became the House of Orange. This pitched it into the Protestant side in the Wars of Religion, during which the town was badly damaged. In 1568 the Eighty Years' War began with William as Stadtholder of Holland leading the bid for independence of the Netherlands from Spain. William the Silent was assassinated in Delft in 1584. It was his son, Maurice of Nassau (Prince of Orange after his elder brother died in 1618), with the help of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, who solidified the independence of the Dutch republic.

As an independent enclave within France, Orange became an attractive destination for Protestants and a Huguenot stronghold. William III of Orange, who ruled England as William III of England, was the last Prince of Orange to rule the principality. The principality was captured by the forces of Louis XIV under François Adhémar de Monteil Comte de Grignan, in 1672 during the Franco-Dutch War, and again in August 1682, but William did not concede his claim to rule. In 1702, William III died childless and the right to the principality became a matter of dispute between Frederick I of Prussia and John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz, who both claimed the title 'Prince of Orange'. In 1702 also, Louis XIV of France enfeoffed François Louis, Prince of Conti, a relative of the Châlon dynasty, with the Principality of Orange, so that there were three claimants to the title.

Finally in 1713 in the Treaty of Utrecht, Frederick I of Prussia ceded the Principality to France (without surrendering the princely title) in which cession the Holy Roman Empire as suzerain concurred, though John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz, the other claimant to the principality, did not concur. Only in 1732, with the Treaty of Partage, did John William Friso's successor William IV, Prince of Orange, renounce all his claims to the territory, but again (like Frederick I) he did not renounce his claim to the title. In the same treaty an agreement was made between both claimants, stipulating that both houses be allowed to use the title.

In 1713, after Orange was officially ceded to France, it became a part of the Province of the Dauphiné.

Following the French Revolution of 1789, Orange was absorbed into the French département of Drôme in 1790, then Bouches-du-Rhône, then finally Vaucluse.

In 1814 after the defeat of Napoleon, the Dutch Republic was not revived but replaced into the Kingdom of the United Netherlands, under a King of the House of Orange-Nassau. In 1815 the Congress of Vienna took care of a French sensitivity by stipulating that the Kingdom of the Netherlands would be ruled by the House of Oranje-Nassau – "Oranje", not "Orange" as had been the custom until then. The English language, however, continues to use the term Orange-Nassau.[2]

Today, Dutch crown princess Amalia carries the title "Princess of Orange" in the official form of Prinses van Oranje.

Constituent Parts

The territory of the principality was 180 square km, 19 km long and 15 km wide. It was oriented with its base on the eastern bank of the Rhône extending east to west towards Dentelles de Montmirail. It also included several enclaves in the Dauphiné.

The principality comprised the following towns:

- Bouchet (only the 13th through the 14th century);[4]

- Causans (today part of the Jonquières[5]) ;

- Châteauneuf-de-Redortier (today part of the Suzette[6]) ;

- Condorcet (enclave in the Dauphiné)[7]

- Courthézon;[8]

- Derboux (today, part of Mondragon[9]) ;

- Gigondas;[10]

- Jonquières;[11]

- Monbrison[12] · [7] (enclave de la Principauté d'Orange dans le Dauphiné, jouxtant le Comtat Venaissin)

- Montmirail ;

- Montréal-les-Sources[12]

- Montségur [7]until its reattachment to the County of Grignan in Provence

- Orange;[13]

- Saint-Blaise, today a dependency of Bollène [13] (it consists of the ruin of a castle and a Roman era chapel)

- Suze-la-Rousse[12]

- Suzette;[14]

- Saint-André-de-Ramières (today part of Gigondas) ;

- Tulette,[12] rom the 12th to the 16th century, when it was annexed to the Dauphiné;

- Villebois-les-Pins[12] (enclave en Dauphiné), where, in 1256, there was a tribute from Lord Guillaume des Baux, Prince of Orange, to the Seneschal of Provence

- Violès.[15]

Defences

Geography

The capital of the principality was the castle, fortress and town of Orange. The castle and fortress sat on an outcropping of rock from the Colline Saint-Eutrope with the town below. The natural defense provided by the escarpment allowed the princes to control all the approaches to Orange and the surrounding countryside, including the passage up and down the Rhone, and the approaches from the Mediterranean. It also made the fortress impervious to the military technology of the time until Louis XIV overwhelmed it with his armies in 1672.

- « Du sommet de la colline, s’élevant à une centaine de mètres au-dessus de la plaine, et dominant la Ville d’Orange, la vue embrasse l’admirable paysage du Comtat jusqu’au-delà d’Avignon, et des Cévennes au mont Ventoux.

- Enfin ses flancs plantés d’arbres forment un décor grandiose aux imposants vestiges romains, constituant dans leur ensemble un site dont la protection et la conservation s’imposent au premier chef.[16] »

The Château

In the 12th century, Tiburge d’Orange, daughter Count Raimbaud of Nice, rebuilt the Roman walls of the town and rehabilitated the ancient "castrum Aurasice". In the 14th century, the Les Baux princes of Orange consolidated the donjon and rampart of the chateau in order to resist the assaults of the "grandes compagnies" that were devastating Provence at the time. The population of the town was concentrated around the fortress in an area much smaller than the ancient Roman town. Prince Jean de Chalon added three wings to the dungeon in the last years of the century, which gave it a square shape.

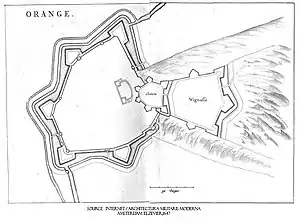

The Citadel of the Princes

By the 17th century, the chateau had suffered damage due to the French Wars of Religion. Much of the essential defenses were in need of complete rebuilding. The incumbent prince of Orange, the celebrated general Maurice of Nassau, executed a plan by the architect Servole to build a fortress incorporating the modern science of fortification he had pioneered in his wars in the Netherlands. The fortress was composed of three parts: the 14th century castle, the curtain wall, and the "Vignasse", an esplanade, says Joseph of Pisa, capable of containing 10,000 men at arms. The entire complex and the city were surrounded by moats and Bastion fort walls to protect against cannon fire similar to the fortifications of towns in the Netherlands.

When completed, the citadel consisted of 11 bastions connected by curtain walls and ditches. It was built with walls of extraordinary thickness extending over the whole hill. It was heavily fortified and garrisoned. In 1672, in reprisal for the young William III, prince of Orange and "stadtholder" of Holland defending the interests of his nation and of the Protestant religion, Louis XIV instructed the count of Grignan to lay siege to the citadel and to destroy it. Gunpowder was used to demolish the enormous walls of which one can see today some vestiges on the hill. In 1991, an excavation studied the architectural and military features.[17]

Later uses

Due to its connection with the Dutch royal family, Orange gave its name to other Dutch-influenced parts of the world, such as the Orange River and the Orange Free State in South Africa, and Orange County in the U.S. state of New York. The town of Orange, Connecticut is named after the principality.

The orange portion of the flag of Ireland, invented in 1848, represents Irish Protestants, who were grateful for their rescue by William III of England ("William of Orange") in 1689–1691. The flag of South Africa from 1928 to 1994 had an orange upper stripe and was very similar to the old Dutch flag, also called Prince's Flag, because it was inspired by the history of the Afrikaners, who are chiefly of Dutch descent.

The flag of New York City and the flag of Albany, New York (which was originally known as Fort Orange) also each have an orange stripe to reflect the Dutch origins of those cities. In turn, orange is included in the team colors of the New York Mets, the New York Knicks, and the New York Islanders. It is also a team color of the San Francisco Giants, which was a New York team until 1957.

The color orange is still the national color of the modern Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Dutch flag originally had an orange stripe instead of a red, and today an orange pennant is still flown above the flag on Koningsdag. Dutch national sports teams usually compete in orange, and a wide variety of orange-colored items are displayed by Dutch people on occasions of national pride or festivity.

See also

References

- George Ripley And Charles A. Dana (1873). The New American Cyclopædia. 16 volumes complete. article on Principality of Orange: D. Appleton And Company.

- Couvée, D.H.; G. Pikkemaat (1963). 1813-15, ons koninkrijk geboren. Alphen aan den Rijn: N. Samsom nv. pp. 119–139.

- George Ripley And Charles A. Dana (1873). The New American Cyclopædia. 16 volumes complete. article on Principality of Orange: D. Appleton And Company.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jean Pagnol (1979). Valréas et "l'enclave des papes" tome 1 (in French). Aubenas: Lienhart. p. 297.

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=62303

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=62304

- Charles-Laurent SALCH (1979). Dictionnaire des châteaux et des fortifications du Moyen-Âge en France (in French). Strasbourg: PUBLITOTAL. p. 1287. ISBN 2-86535-070-3.

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=10793

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=62306

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=15480

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=17888

- Michel de la Torre (1992). Drôme: le guide complet de ses 371 communes (in French). DESLOGIS-LACOSTE. p. Suze-la-Rousse. ISBN 2-7399-5026-8.

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=25645

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=36948

- http://cassini.ehess.fr/cassini/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=40788

- Extrait du rapport de la Commission supérieure des sites, mars 1933 (dossier Ministère).

- Guide historique Orange ville d'art et d'histoire