Prophylactic salpingectomy

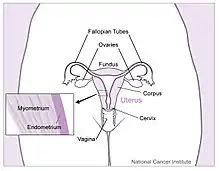

Prophylactic salpingectomy is a preventative surgical technique performed on patients who are at higher risk of having ovarian cancer, such as individuals who may have pathogenic variants of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.[1] Originally salpingectomy was used in cases of ectopic pregnancies.[2] As a preventative surgery however, it involves the removal of the fallopian tubes. By not removing the ovaries this procedure is advantageous to individuals who are still of child bearing age. It also reduces risks such as cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis which are associated with removal of the ovaries.[1]

Indications

In 2013 in America alone there were 22,000 cases of ovarian cancer diagnosed and reported. Of these 10% were due to an inherited disorder.[3] It is also the fifth most common cancer related cause of death in women.[4] The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are the most common inherited genetic mutations which lead to ovarian cancer.[3] As such a preventative surgery such a prophylactic salpingectomy is thought to decrease this risk of getting cancer. Recent research has shown that ovarian cancer may not originate in the ovaries themselves but start in the fallopian tubes.[5] It is therefore thought that in women who are of child bearing age the more common salpingo-oophorectomy may not be the correct surgery of choice.[1]

| Gene Mutation | Risk of Developing Ovarian Cancer by age of 70 (%) |

| No Mutation | 1.4 |

| BRCA1 | 39-46 |

| BRCA2 | 10-27 |

A bilateral prophylactic salpingectomy with ovarian conservation was proposed as a “middle-ground" method of primary prevention, with the benefit of removing potential tissue of origin without the risks of surgical menopause. This method has been proposed for clinical trials in high-risk patients, but results are not currently available.[6]

Potential indications for Prophylactic Salpingectomy:

- At the time of abdominal or pelvic surgery instead of tubal ligation or hysterectomy

- Women at a high-risk of developing serous ovarian cancer due to their inheritance of a germline mutation in a cancer predisposition gene, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, once childbearing is complete.

- Interim procedure in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, enabling them to delay oophorectomy[3][4]

In 2013, the SGO released a clinical practice statement recommending that a bilateral salpingectomy should be considered “at the time of abdominal or pelvic surgery, hysterectomy, or in lieu of tubal ligation”. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that the procedure should be considered for population-risk patients: those without increased risk based on personal or family history, but they were clear that the approach to pelvic surgery, hysterectomy, or sterilization should not change simply to increase the chances of completing bilateral salpingectomy. The proposed plan of the British Columbia Ovarian Cancer Research Group program, involved performing opportunistic salpingectomy with benign hysterectomy or in lieu of bilateral tubal ligation for permanent contraception. It is suggested that this approach would yield a 20-40 percent population risk reduction for ovarian cancer over the next 20 years. However, overall there is insufficient evidence to support this practice as a safe alternative and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy remains the recommended standard of care for high-risk women.[7]

Clinical Trials and Evidence

There are currently 2 ongoing clinical trials regarding prophylactic salpingectomy;

1) A study focusing on prophylactic salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy (PSDO) in reducing risk of ovarian cancer. PSDO will result in the patient not immediately going through the menopause after the surgery, this will only happen once the ovaries are removed. Study is estimated to be complete in August 2018.

2) Another study looking at BRCA-positive women who are reluctant to undergo prophylactic surgery – this refusal increase risk of developing serious pelvic carcinoma. This study looks at the removal of the fimbrae structures of the ovaries. Results for this study are expected in October 2017.

BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are recommended salpingectomy at around the age of 40 to decrease their risk of ovarian cancer. Salpingectomy is most effective if performed before the natural menopause occurs, it was also found that there is no increased complication risks when salpingectomy is done at the same time as hysterectomy.[8]

A Nationwide study[9] found statistically lower risk of ovarian cancer among women with previous salpingectomy when compared to the unexposed population. Bilateral salpingectomy is associated with a 50% decrease in ovarian cancer risk compared to unilateral salpingectomy (the removal of both or one fallopian tubes). Most protective effect was seen in women who had a bilateral salpingectomy. High-Grade Serous Carcinoma (HGSC) is usually driven by BRCA gene mutations – it was hypothesised that a decrease risk of ovarian cancer observed among women with salpingectomy reflects the effect of the removed tubal epithelium (fallopian tube).

Those at risk are recommended sapling-oophorectomy at around the age of 40/after child-bearing to reduce ovarian cancer risk, and also reduces breast cancer too. Removal of healthy ovaries is also associated with negative health effects due to oestrogen deficiency, leaving the ovaries intact within the reproductive system is balanced with the remaining breast cancer risk. This was the first population based study describing the association between removing fallopian tubes and decreasing risk of ovarian cancer.[9]

Risks of Procedure

Surgical risks

Due to the mean age of the procedure being 36 years, age-related complications play a minimal factor during and after surgery. Older patients have the additional risk of coexisting age-related medical conditions, which would possibly cause complications in surgery. Surgery causes extra stress which requires an increased functional demand of the patient – geriatric patients may not be able to meet this, so for the average prophylactic salpingectomy recipient this is not significant.[10]

It has also been proven that the procedure does not increase normal surgical/post operative risks. It does, however, carry the same standard risks as a normal surgery. Complications associated with the surgical procedure include; reaction to anaesthesia, excessive bleeding, injury to other organs, and infection.[11]

One study also confirmed after reviewing 21,000 procedures, that there was no increased risk in hysterectomy plus bilateral salpingectomy compared to hysterectomy alone. This may indicate that there are no surgical risks related to salpingectomy alone. They also found that prophylactic salpingectomy did not increase length of stay or the likelihood of readmission or blood transfusion. This is a reassuring and highly interesting result as both of these complications were voiced as surgical concerns at the time prophylactic salpingectomy was first proposed.[12]

Long-term effects

There is no significant increased risk in future hospital admissions after a prophylactic salpingectomy. Each year over 225,000 women experience ovarian cancer, and as there are currently no effective screening tests, prophylactic salpingectomy removes this risk effectively for those where it is appropriate, as the procedure is often only done to those with 50% or higher risk of ovarian cancer in their lifetime.

However, some groups have found that unilateral salpingectomy seemed to impair ovarian function. Less blood flow to the ovary and a reduced antral follicle count was seen shortly after surgery. It is hypothesised that this will ameliorate as time goes on, but for now it is known as a short-term effect.[13]

In vitro fertilisation after salpingectomy

A study in 1998 showed that salpingectomy had no detrimental effect on ovarian response after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment, which is very reassuring for those wanting to undergo the procedure to prevent cancer or cysts if they want to have children in the future. IVF treatment and the outcome of IVF remains consistent in two cohorts of patients – one with salpingectomy and the other without. In patients with hydrosalpinx, it is highly beneficial to have prophylactic salpingectomy before conceiving due to potential difficulties in achieving pregnancy.[14]

Effects on testosterone

Medical experience with bilateral salpingectomy over the past 5–10 years gave us confidence that the surgical removal of the tubes would not result in the negative consequences of oophorectomy such as impaired sexuality and osteoporosis due to reduced testosterone levels.[15]

Similar Procedures

Delayed oophorectomy

Early salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy allows for the postponement of premature surgical menopause and is therefore associated with an improved quality of life.[1]

Emergency salpingectomy

Laparotomy with salpingectomy is the recommended treatment for ectopic pregnancy.[16]

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Currently, the only intervention proven to reduce ovarian cancer risk is bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) at age 35–40 for BRCA1 carriers or age 40–45 for BRCA2, which has been shown to decrease incidence by 80-96%. During BSO both ovaries and both fallopian tubes are removed in one operation. However, only 60-70% of BRCA mutation carriers undergo BSO currently, which is related to the generation of premature surgical menopause in the patient and the associated risks of oestrogen deficiency, urogenital atrophy, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.[1]

References

- Kwon, Janice S.; Tinker, Anna; Pansegrau, Gary; McAlpine, Jessica; Housty, Melissa; McCullum, Mary; Gilks, C. Blake (January 2013). "Prophylactic Salpingectomy and Delayed Oophorectomy as an Alternative for BRCA Mutation Carriers". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e3182783c2f. PMID 23232752.

- Strandell, A.; Lindhard, A.; Waldenström, U.; Thorburn, J. (2001-06-01). "Prophylactic salpingectomy does not impair the ovarian response in IVF treatment". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 16 (6): 1135–1139. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.6.1135. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 11387282.

- Holman, Laura L.; Friedman, Sue; Daniels, Molly S.; Sun, Charlotte C.; Lu, Karen H. (2014). "Acceptability of prophylactic salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy as risk-reducing surgery among BRCA mutation carriers". Gynecologic Oncology. 133 (2): 283–286. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.030. PMC 4035022. PMID 24582866.

- Yoon, Sang-Hee; Kim, Soo-Nyung; Shim, Seung-Hyuk; Kang, Soon-Beum; Lee, Sun-Joo (2016). "Bilateral salpingectomy can reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in the general population: A meta-analysis". European Journal of Cancer. 55: 38–46. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.003. PMID 26773418.

- Venturella, Roberta; Morelli, Michele; Lico, Daniela; Cello, Annalisa Di; Rocca, Morena; Sacchinelli, Angela; Mocciaro, Rita; D'Alessandro, Pietro; Maiorana, Antonio (2015). "Wide excision of soft tissues adjacent to the ovary and fallopian tube does not impair the ovarian reserve in women undergoing prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy: results from a randomized, controlled trial". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (5): 1332–1339. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.004. PMID 26335129.

- Greene, Mark H.; Mai, Phuong L.; Schwartz, Peter E. (January 2011). "Does bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian retention warrant consideration as a temporary bridge to risk-reducing bilateral oophorectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers?". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204 (1): 19.e1–19.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.038. PMC 3138129. PMID 20619389.

- Kwon, Janice S.; McAlpine, Jessica N.; Hanley, Gillian E.; Finlayson, Sarah J.; Cohen, Trevor; Miller, Dianne M.; Gilks, C. Blake; Huntsman, David G. (2015). "Costs and Benefits of Opportunistic Salpingectomy as an Ovarian Cancer Prevention Strategy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 125 (2): 338–345. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000000630. PMID 25568991.

- Schenberg, Tess; Mitchell, Gillian (2014-01-01). "Prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy as a prevention strategy in women at high-risk of ovarian cancer: a mini-review". Frontiers in Oncology. 4: 21. doi:10.3389/fonc.2014.00021. PMC 3918654. PMID 24575389.

- Falconer, Henrik; Yin, Li; Grönberg, Henrik; Altman, Daniel (2015-02-01). "Ovarian Cancer Risk After Salpingectomy: A Nationwide Population-Based Study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 107 (2): dju410. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju410. ISSN 0027-8874. PMID 25628372.

- Turrentine, F.E.; Wang, H.; Simpson, V.B.; Jones, R.S. (2008). "Surgical Risk Factors, Morbidity, and Mortality in Elderly Patients". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 68: S13. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(08)70016-7.

- "The Cochrane Library: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1996. doi:10.1002/14651858. hdl:2328/35732.

- McAlpine, Jessica N.; Hanley, Gillian E.; Woo, Michelle M.M.; Tone, Alicia A.; Rozenberg, Nirit; Swenerton, Kenneth D.; Gilks, C. Blake; Finlayson, Sarah J.; Huntsman, David G.; Miller, Dianne M.; Ovarian Cancer Research Program of British Columbia (2014). "Opportunistic salpingectomy: uptake, risks, and complications of a regional initiative for ovarian cancer prevention". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 210 (5): 471.e1–471.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.003. PMID 24412119.

- Chan, C. C. W.; Ng, E. H. Y.; Li, C. F.; Ho, P. C. (2003-10-01). "Impaired ovarian blood flow and reduced antral follicle count following laparoscopic salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy". Human Reproduction. 18 (10): 2175–2180. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg411. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 14507841.

- Lass, Amir; Ellenbogen, Adrian; Croucher, Carolyn; Trew, Geoff; Margara, Raul; Becattini, Carolina; Winston, Robert M. L (1998-12-01). "Effect of salpingectomy on ovarian response to superovulation in an in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer program". Fertility and Sterility. 70 (6): 1035–1038. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00357-4. PMID 9848291.

- Castelo-Branco, C.; Palacios, S.; Combalia, J.; Ferrer, M.; Traveria, G. (2009-12-01). "Risk of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and associated factors in a cohort of oophorectomized women". Climacteric. 12 (6): 525–532. doi:10.3109/13697130903075345. ISSN 1473-0804. PMID 19905904.

- Dickens, B.M.; Faúndes, A.; Cook, R.J. (2003). "Ectopic pregnancy and emergency care: ethical and legal issues". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 82 (1): 121–126. doi:10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00175-9. PMID 12834958.