Prussia (region)

Prussia (Old Prussian: Prūsa; German: Preußen; Lithuanian: Prūsija; Polish: Prusy; Russian: Пруссия) is a historical region in Europe on the south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, that ranges from the Gulf of Gdańsk in the west to the end of the Curonian Spit in the east and extends inland as far as Masuria. Tacitus's Germania (98 CE) is the oldest known record of an eyewitness account on the territory and its inhabitants.[1] Pliny the Elder had already confirmed that the Romans had navigated into the waters beyond the Cimbric peninsula (Jutland). Suiones, Sitones, Goths and other Germanic people had settled to the east and west of the Vistula River, adjacent to the Aesti, who lived further to the east.[2][3]

The region's inhabitants of the Middle Ages have first been called Bruzi in the brief text of the Bavarian Geographer and since been referred to as Old Prussians, who, beginning in 997, repeatedly defended themselves against conquest attempts by the newly created Duchy of the Polans.[4] The territories of the Old Prussians and the neighboring Curonians and Livonians were politically unified in the 1230s under the State of the Teutonic Order. The former kingdom and later state of Prussia (1701–1947) derived its name from the region. Prussia was politically divided between 1466 and 1772, with western Prussia under protection of the Crown of Poland and eastern Prussia a Polish–Lithuanian fief until 1660. The unity of both parts of Prussia remained preserved by retaining its borders, citizenship and autonomy until western and eastern Prussia were also politically reunited under the German Kingdom of Prussia (which despite the name was governed in Berlin, Brandenburg). Since its conquest by the Soviet Army in 1945 and the expulsion of the German-speaking inhabitants Prussia remains divided between northern Poland (most of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship), Russia's Kaliningrad exclave, and southwestern Lithuania (Klaipėda Region).[5][1]

Prehistory and early history

Indo-European settlers first arrived in the region during the 4th millennium BC, which in the Baltic would diversify into the satem Balto-Slavic branch which would ultimately give rise to the Balts as the speakers of the Baltic languages.[5] The Balts would have become differentiated into Western and Eastern Balts in the late 1st millennium BC. The region was inhabited by ancestors of Western Balts – Old Prussians, Sudovians/Jotvingians, Scalvians, Nadruvians, and Curonians while the eastern Balts settled in what is now Lithuania, Latvia and Belarus.[5][6][7]

The Greek explorer Pytheas (4th century BC) may have referred to the territory as Mentenomon and to the inhabitants as Guttones (neighbours of the Teutones, probably referring to the Goths).[8][9] A river to the east of the Vistula was called the Guttalus, perhaps corresponding to the Nemunas, the Łyna, or the Pregola. In AD 98 Tacitus described one of the tribes living near the Baltic Sea (Latin: Mare Suebicum) as Aestiorum gentes and amber-gatherers.[10]

The Vikings started to penetrate the southeastern shores of the Baltic Sea in the 7th and 8th centuries. The largest trade centres of the Prussians, such as Truso and Kaup, seem to have absorbed a number of Norse people. Prussians used the Baltic Sea as a trading route, frequently travelling from Truso to Birka (in present-day Sweden).[11]

At the end of the Viking Age, the sons of Danish kings Harald Bluetooth and Cnut the Great launched several expeditions against the Prussians. They destroyed many areas in Prussia, including Truso and Kaup, but failed to dominate the population totally. A Viking (Varangian) presence in the area was "less than dominant and very much less than imperial."[12][1]

According to a legend, recorded by Simon Grunau, the name Prussia is derived from Pruteno (or Bruteno), the chief priest of Prussia and brother of the legendary king Widewuto, who lived in the 6th century. The regions of Prussia and the corresponding tribes are said to bear the names of Widewuto's sons — for example, Sudovia is named after Widewuto's son Sudo. The territory was probably identified as Brus in the 8th-century map of the Bavarian Geographer. In New Latin the area is called Borussia and its inhabitants Borussi.[13]

The Old Prussians spoke a variety of languages, with Old Prussian belonging to the Western branch of the Baltic language group. Old Prussian, or related Western Baltic dialects, may have been spoken as far southeast as Masovia and even Belarus in the early medieval period, but these populations would probably have undergone Slavicization before the 10th century.[14]

Meanwhile, the big part of later Prussia, west of the Vistula and south of the Osa River, has been inhabited by Lechitic (Polish and Pomeranian) tribes.[1]

Old Prussians

In the first half of the 13th century, Bishop Christian of Prussia recorded the history of a much earlier era. Adam of Bremen mentions Prussians in 1072.[15]

After the Christianisations of the West Slavs in the 10th century, the state of the Polans was established and there were first attempts at conquering and baptizing the Baltic peoples. Bolesław I Chrobry sent Adalbert of Prague in 997 on a military and Christianizing mission. Adalbert, accompanied by armed guards, attempted to convert the Prussians to Christianity. He was killed by a Prussian pagan priest in 997.[16] In 1015, Bolesław sent soldiers again, with some short-lived success, gaining regular paid tribute from some Prussians in the border regions, but it did not last. Polish rulers sent invasions to the territory in 1147, 1161–1166, and a number of times in the early 13th century. While these were repelled by the Prussians, the Chełmno Land became exposed to their frequent raids.[17]

At that time, Pomerelia belonged to the diocese of Włocławek, while Chełmno belonged to the diocese of Płock.[5]

Christianization and the Teutonic Knights

In the beginning of the 13th century, Konrad of Mazovia had called for Crusades and tried for years to conquer Prussia, but failed. Thus the pope set up further crusades. Finally the Duke invited the Teutonic Knights to fight the inhabitants of Prussia in exchange for a fief of Chełmno Land. Prussia was conquered by the Teutonic Knights during the Prussian Crusade and administered within their State of the Teutonic Order, which begins the process of Germanization in the area.[17]

After the acquisition of Pomerelia in 1308–1310, the meaning of the term Prussia was widened to include areas west of the Vistula.

The city of Königsberg (modern Kaliningrad) was founded in 1255, and joined the Hanseatic League in 1340. Danzig (Gdańsk) followed in 1361. Since Prussia was connected to the European trade network spanning via the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.[18]

With the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Prussia was divided into eastern and western parts. The western part became the province of Royal Prussia adjacent to the Kingdom of Poland, while the eastern part of the monastic state became a fief of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[19]

In 1492, a life of Saint Dorothea of Montau, published in Marienburg (Malbork), became the first printed publication in Prussia.

The Chronicon terrae Prussiae is the first major chronicle of the Teutonic Order in Prussia

The Chronicon terrae Prussiae is the first major chronicle of the Teutonic Order in Prussia.jpg.webp)

Early modern era

In 1525, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, Albert of Brandenburg, a member of a cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern, adopted the Lutheran faith, resigned his position, and assumed the title of "Duke of Prussia". In a deal partially brokered by Martin Luther, the Duchy of Prussia became the first Protestant state and a vassal of Poland. The ducal capital of Königsberg, now Kaliningrad, became a centre of learning and printing through the establishment of the Albertina University in 1544 for not only the dominant German culture, but also the thriving Polish and Lithuanian communities as well. It was in Königsberg that the first Lutheran books in Polish, Lithuanian, and Prussian languages were published.[20]

Rulership of Ducal Prussia passed to the senior Hohenzollern branch, the ruling Margraves of Brandenburg, in 1618, and Polish sovereignty over the duchy ended in 1657 with the Treaty of Wehlau. Because Ducal Prussia lay outside of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick I achieved the elevation of the duchy to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701. The former ducal lands became known as East Prussia.[21]

An autonomous region of Royal Prussia was ruled by the King of Poland-Lithuania as the official language was German. Its population consisted of Polish Catholics (Chełmno Land, Kociewie, Kashubia and Sztum) and German Protestants (Thorn/Toruń, Gdańsk/Danzig, the Żuławy Wiślane and Elbląg/Elbing). Gdańsk had about 50,000 inhabitants. Toruń and Elbląg were also large cities, with 10,000 citizens. Gdańsk and the Żuławy Wiślane had a sizeable Dutch Calvinists and Mennonites community. Lithuanian culture thrived in the western part of the region known as Lithuania Minor, while the Kursenieki lived along the coast in the vicinity of the Curonian and Vistula Spits.

Royal Prussia was annexed from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Kingdom of Prussia during the late 18th-century Partitions of Poland and administered within West Prussia.[22]

The Old Prussian language had mostly disappeared by 1700. The last speakers may have died in the plague and famine that ravaged Prussia in 1709 to 1711.[23]

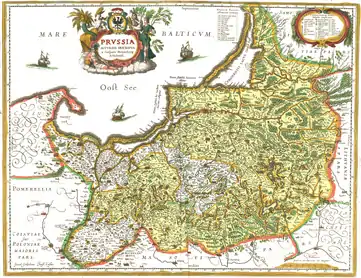

Map by Caspar Henneberg, Elbing, 1576: Duchy and Royal Prussia originally with same colour (for the duchy the colour was added later)

Map by Caspar Henneberg, Elbing, 1576: Duchy and Royal Prussia originally with same colour (for the duchy the colour was added later) Prussia after 1466: light grey – Duchy of Prussia.

Prussia after 1466: light grey – Duchy of Prussia.

coloured – Royal Prussia with its Voivodeships as a province of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Gdańsk was the biggest city and main port of Poland in 15th–18th century.

Gdańsk was the biggest city and main port of Poland in 15th–18th century.

Modern era

Upon the establishment of the Prussian Kingdom, the region became a single province, later divided again into West and East and the northernmost area of Greater Poland (Sępólno Krajeńskie, Złotów and Wałcz) was adjoined to it. Its population remained partly Polish and partly German, partly Catholic and partly Lutheran (both divisions overlapping especially in the west).

Though the Kingdom of Prussia was a member of the German Confederation from 1815 to 1866, the provinces of Posen and Prussia were not a part of Germany[lower-alpha 1] until the creation of the German Empire in 1871 during the unification of Germany.[24]

As agreed upon in the Treaty of Versailles, most of West Prussia that had belonged to the Kingdom of Prussia and the German Empire since the Partitions of Poland was ceded to the Second Polish Republic. Danzig became a free city under the protection of the League of Nations. East Prussia, minus the Memelland, received some districts of former West Prussia and remained within the German Weimar Republic.[25]

According to the Potsdam Conference in 1945 after World War II, the German part of Prussia was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union, which divided its part further between the Lithuanian SSR and the Russian SFSR. Warmia and Masuria are now in Poland, while northern East Prussia (minus the former Memelland which is now the Klaipėda region of Lithuania) forms the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave of the Russian Federation.[26]

Beginning in 1944 with the westward advance of Soviet troops the native German-speaking population was subject to forced relocation or reeducation. For additional information, see Expulsion of Germans from Poland.

Today, the region's territory under Polish rule (with Lębork and Bytów) covers about 45,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) and has over 4,000,000 inhabitants, while the Russian territory covers 15,000 km2 (5,800 sq mi) and is home to almost 1,000,000 people.

See also

References

- However, the constitution of the short-lived Frankfurt Parliament incorporated Prussia and the western and northern parts of the Province of Posen into Germany from 1848 to 1851.

- "MILESTONES OF BALTIC PRUSSIAN HISTORY". Kompiuterinės lingvistikos centras. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Sir Thomas D. Kendrick (24 October 2018). A History of the Vikings. Taylor & Francis. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-1-136-24239-7.

- Kemp Malone (1925). "The Suiones of Tacitus". The American Journal of Philology. Jstor. 46 (2): 170–176. doi:10.2307/289144. JSTOR 289144.

- Diego Ardoino. "The Bavarian Geographer and the Old Prussians" (PDF). University of Pisa. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- Agris Dzenis (March 2, 2016). "The Old Prussians: the Lost Relatives of Latvians and Lithuanians". deep baltic. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- "Prussia, region". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- AUDRONE B. WILLEKE (1990). "The Image of the Heathen Prussians in German Literature". Colloquia Germanica. Jstor. 23 (3/4): 223–239. JSTOR 23980816.

- Sledzenia Poczatkow Narodu Litewskiego I Poczatki Jego Dziejow. Marcinowski. 1837. pp. 222–.

- "Zur Urgeschichte der Deutschen". book-city. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Audrone Bliujiene. "LITHUANIAN AMBER ARTIFACTS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE FIRST MILLENNIUM AND THEIR PROVENANCE WITHIN THE LIMITS OF EASTERN BALTIC REGION". Academia. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Gregory Cattaneo (February 14, 2009). "The Scandinavians in Poland: a re-evaluation of perceptions of the Vikings" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. S2CID 67763423. Retrieved September 6, 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jones, Gwyn (2001). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-19-280134-0.

- Gerald J. Larson, C. Scott Littleton, Jaan Puhvel (1974). Myth in Indo-European Antiquity. University of California Press. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-520-02378-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Endre Bojt r (1 January 1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- Rasma Lazda. "Adam of Bremen". Brill. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- "St. Adalbert", The Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907

- Max Töppen (1853). Geschichte der preussischen Historiographie von P.v. Dusburg bis auf K. Schütz: oder, Nachweisung und Kritik gedruckten und ungedruckten Chroniken zur Geschichte Preussens unter der Herrschaft des deutschen Ordens. Hertz.

- Paul Halsall. "Medieval Sourcebook: Privileges Granted to German Merchants at Novgorod, 1229". Fordham. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5.

- Albertas Juška. "Das litauische Siedlungsgebiet in Ostpreussen; Angaben zur Bevölkerungsstatistik". LIETUVOS EVANGELIKŲ LIUTERONŲ. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Karin Friedrich. "Brandenburg-Prussia, 1466-1806: The Rise of a Composite State". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- Karin Friedrich (24 February 2000). The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58335-0.

- Klussis, Mikkels (2006). "Preface". Dictionary of Revived Prussian (PDF). Institut Européen des Minorités Ethniques Dispersées. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26.

- James J. Sheehan; James John Sheehan (1993). German History, 1770-1866. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820432-9.

- Eugen Joseph Weber. "A modern history of Europe : men, cultures, and societies from the Renaissance to the present". Archive. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- United States (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1224–.

External links

- Shennan, Margaret. The Rise of Brandenburg-Prussia. London: Routledge, 1995

- Feuchtwanger, E. J. Prussia: Myth and Reality, The Role of Prussia in German History. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prussia. |