Pupillary response

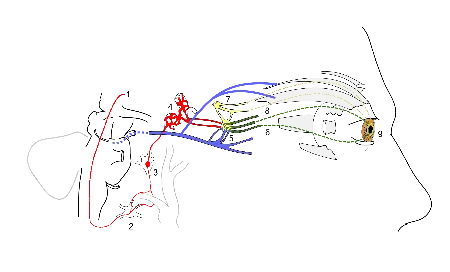

Pupillary response is a physiological response that varies the size of the pupil, via the optic and oculomotor cranial nerve.

A constriction response (miosis),[1] is the narrowing of the pupil, which may be caused by scleral buckles or drugs such as opiates/opioids or anti-hypertension medications. Constriction of the pupil occurs when the circular muscle, controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS), contracts.

A dilation response (mydriasis), is the widening of the pupil and may be caused by adrenaline, anti-cholinergic agents or drugs such as MDMA, cocaine, amphetamines, dissociatives and some hallucinogenics. Dilation of the pupil occurs when the smooth cells of the radial muscle, controlled by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), contract.

The responses can have a variety of causes, from an involuntary reflex reaction to exposure or inexposure to light—in low light conditions a dilated pupil lets more light into the eye—or it may indicate interest in the subject of attention or arousal, sexual stimulation,[2] uncertainty,[3] decision conflict,[4] errors[5] or increasing cognitive load[6] or demand. The responses correlate strongly with activity in the locus coeruleus neurotransmitter system.[7][8][9] The pupils contract immediately before REM sleep begins.[10] A pupillary response can be intentionally conditioned as a Pavlovian response to some stimuli.[11]

The latency of pupillary response (the time in which it takes to occur) increases with age.[12] Use of central nervous system stimulant drugs and some hallucinogenic drugs can cause dilation of the pupil.[13]

In ophthalmology, intensive studies of pupillary response are conducted via videopupillometry.[14]

Anisocoria is the condition of one pupil being more dilated than the other.

| Constriction (Parasympathetic) | Dilation (Sympathetic) | |

|---|---|---|

| Muscular mechanism | Relaxation of iris dilator muscle, activation of iris sphincter muscle | Activation of iris dilator muscle, relaxation of iris sphincter muscle |

| Cause in pupillary light reflex | Increased light | Decreased light |

| Other physiological causes | Accommodation reflex | Fight-or-flight response |

| Corresponding non-physiological state | Miosis | Mydriasis |

See also

References

- Ellis CJ (November 1981). "The pupillary light reflex in normal subjects" (PDF). The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 65 (11): 754–9. doi:10.1136/bjo.65.11.754. PMC 1039657. PMID 7326222.

- Hess EH, Polt JM (August 1960). "Pupil size as related to interest value of visual stimuli". Science. 132 (3423): 349–50. Bibcode:1960Sci...132..349H. doi:10.1126/science.132.3423.349. PMID 14401489.

- Nassar MR, Rumsey KM, Wilson RC, Parikh K, Heasly B, Gold JI (June 2012). "Rational regulation of learning dynamics by pupil-linked arousal systems". Nature Neuroscience. 15 (7): 1040–6. doi:10.1038/nn.3130. PMC 3386464. PMID 22660479.

- Lin H, Saunders B, Hutcherson CA, Inzlicht M (May 2018). "Midfrontal theta and pupil dilation parametrically track subjective conflict (but also surprise) during intertemporal choice". NeuroImage. 172: 838–852. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.055. PMID 29107773.

- Decker, Alexandra; Finn, Amy; Duncan, Katherine (2020-11-01). "Errors lead to transient impairments in memory formation". Cognition. 204: 104338. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104338. ISSN 0010-0277.

- Kahneman D, Beatty J (December 1966). "Pupil diameter and load on memory". Science. 154 (3756): 1583–5. doi:10.1126/science.154.3756.1583. PMID 5924930.

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD (2005-07-21). "An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 28 (1): 403–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. PMID 16022602.

- Joshi S, Li Y, Kalwani RM, Gold JI (January 2016). "Relationships between Pupil Diameter and Neuronal Activity in the Locus Coeruleus, Colliculi, and Cingulate Cortex". Neuron. 89 (1): 221–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.028. PMC 4707070. PMID 26711118.

- Murphy PR, O'Connell RG, O'Sullivan M, Robertson IH, Balsters JH (August 2014). "Pupil diameter covaries with BOLD activity in human locus coeruleus". Human Brain Mapping. 35 (8): 4140–54. doi:10.1002/hbm.22466. PMC 6869043. PMID 24510607.

- Lowenstein O, Feinberg R, Loewenfeld IE (April 1963). "Pupillary Movements During Acute and Chronic Fatigue: A New Test for the Objective Evaluation of Tiredness" (PDF). Investigative Ophthalmology. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Company. 2 (2): 138–157. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-19.

- Baker LE (1938). "The Pupillary Response Conditioned to Subliminal Auditory Stimuli". Ohio State University. OCLC 6894644. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Feinberg R, Podolak E (September 1965). Latency of pupillary reflex to light stimulation and its relationship to aging (PDF). Federal Aviation Agency, Office of Aviation Medicine, Georgetown Clinical Research Institute. p. 12. OCLC 84657376. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-20.

- Jaanus SD (1992), "Ocular side effects of selected systemic drugs", Optom Clin, 2 (4): 73–96, PMID 1363080

- Ishikawa S, Naito M, Inaba K (1970). "A new videopupillography". Ophthalmologica. Journal International D'ophtalmologie. International Journal of Ophthalmology. Zeitschrift Fur Augenheilkunde. 160 (4): 248–59. doi:10.1159/000305996. PMID 5439164.